Arawak taino language: Taino language | Britannica

Arawak language family – Sorosoro Sorosoro

Where are the Arawak languages spoken?

This family is by far the South Amerindian language family covering the largest geographic area. The Arawak languages are spoken in South and Central America, on a huge territory stretching from Paraguay to Belize and including Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, French Guyana, Surinam, Guyana, and Honduras.

In the past, Arawak languages were also spoken all over the Antilles and the Gulf of Mexico islands.

Total number of speakers (estimates)

Between 500,000 and 530,000 according to the figures supplied by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (AA, 1999)

Classification

The Arawak language family counts between 53 and 59 active languages at this point, depending on sources. It is the family counting the largest number of languages in South America.

Southern and south-western Arawak subfamily

South Arawak branch

Baure: 55 speakers according to the UNESCO, 5,000 according to AA

Moxo-Ignaciano: 5,000 speakers according to AA

Moxo-Trinitario: 5,000 speakers according to AA

Salumã (alternative name: Enawenê-Nawê): 445 speakers according to the UNESCO, 154 according to AA

Terêna: 19,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 9,800 according to AA

Pareci-Xingu branch

Xingu

Mehinaku: 200 speakers according to the UNESCO, 95 according to AA

Waura: 321 speakers according to the UNESCO, 130 according to AA

Yawalapiti: 10 speakers according to the UNESCO, 135 according to AA

Pareci-Saraveca

Pareci: 10 speakers according to the UNESCO, 135 according to AA

South-west Arawak branch

Piro (alternative names: Maniteneri, Maxineri): 900 speakers according to the UNESCO, 3,000 according to AA

Chontaquiro (Piro dialect?): no available data

Apurina-Ipurina-Cangitil: 2,000 according to the UNESCO and AA

Iñapari: 600 speakers according to the UNESCO, 362 according to AA

Mashko-Piro (Iñapari dialect?): no available data

Campa branch

Ashaninca: 65,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 15,000 to 18,000 according to AA

Asheninca: 18,000 to 25,000 according to AA

Caquinte: 250 speakers according to the UNESCO, 200 to 300 according to AA

Machiguenga: 11,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 7,000 to 12,000 according to AA

Nomatsiguenga: 4,500 speakers according to the UNESCO, 2,500 to 4000 according to AA

Pajonal Campa: 8,000 speakers according to AA

Amuesha (isolate)

Amuesha: 8,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 6,000 to 8,000 according to AA

Northern Arawak subfamily

Rio Branco branch

Mawayana (alternative name: Mapidian, Mawakwa): 10 speakers according to the UNESCO, nearly extinct according to AA

Wapishana: 11,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 10,500 according to AA

Palikur branch

Palikur: 1,800 speakers according to the UNESCO, 1,200 according to AA

Caribbean branch

Garifuna (alternative names: Black Carib, Cariff): 116,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 100,000 according to AA

Ta-Arawak group

Añun-Parauhano: extinct according to the UNESCO, nearly extinct according to AA

Guajiro (alternative name: Wayyuu): 300,000 speakers according to the UNESCO and AA

Arawak (alternative name: Lokono): 2,350 speakers according to the UNESCO, 2,500 according to AA

Northern Amazonian branch

Colombian group

Achagua: 283 speakers according to the UNESCO, 200 according to AA

Cabiyari: 50 speakers according to AA

Piapoco: 3000 speakers according to AA

Yucuna: (alternative name: Chuchuna, Matapi): 600 to 700 speakers according to the UNESCO and AA

Upper Rio Negro group

Baniwa d’Içana (alternative name: Kurripako): 16,000 speakers according to the UNESCO, 3,000 to 4,000 according to AA

Guarequena: 500 speakers according to the UNESCO, 300 according to AA

Tariana: 110 speakers according to the UNESCO, 100(?) according to AA

Orenoque group

Baniwa de Guainia (alternative name: Baniva): 500 speakers according to the UNESCO, 200 (including the Warekana of Xie dialect) according to AA

Bare: 2 speakers according to the UNESCO, nearly extinct according to AA

Mandawaka: nearly extinct according to AA

Moyen Rio Negro group

Kaifana: extinct, according to the UNESCO and AA

Notes on the Arawak languages classification

We hereby follow Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald’s classification (1999).íí

Aikhenvald’s classification (1999).íí

The inner classification of the Arawak languages is under constant debate among linguists and there is no settled classification at this point. Many of these languages lack documentation, and available data is too unsubstantial to build consensus.

As it is often the case with Amerindian languages, the name of a language may actually refer to several languages, and likewise, one and the same language may be known under different names. Plus, depending on sources and the standards by which they distinct a language from a dialect, the number of these languages may vary from 40 to 154.

Are the Arawak languages endangered?

Yes, all the Arawak languages are under more or less critical threats of extinction.

Around 30 of them are said to have disappeared in the course of the 20th Century, or more recently. Kaifana and Mandawaka, for example.

Chances are high that languages like Añun-Paraujano or Chamicuro are also extinct at this point.

Other languages like Bare, Tariana, Cabiyari, Mawayana, Yawalapiti and Baure are threatened with extinction on the very short term, if not already extinct.

The UNESCO considers all the other languages endangered or under threat.

The language sustaining the highest vitality is probably Garifuna, though its future is very uncertain on the long run.

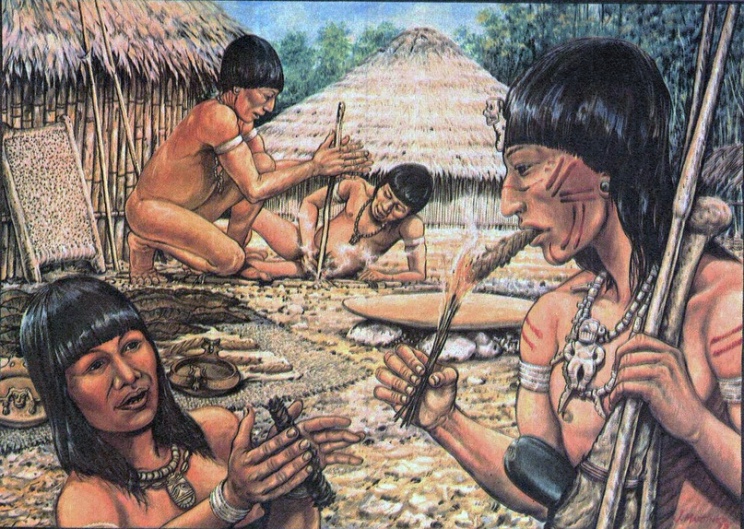

Ethnographic elements

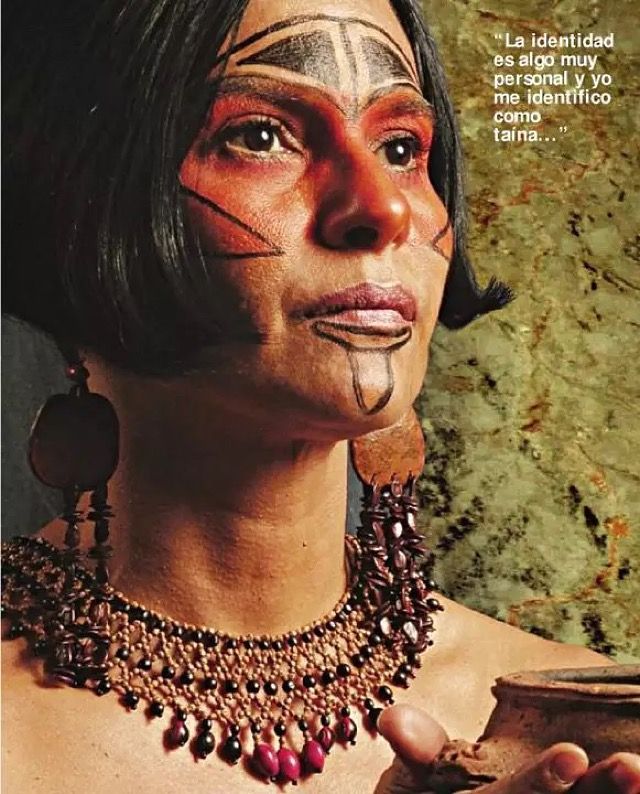

Speakers of the different Arawak languages do not form a culturally homogenous family. Though before colonisation it was possible to make an approximate distinction between the populations of the Caribbean Islands (among which the Taínos, whose language is nowadays extinct) and those who lived in the forested regions of South America.

The Taínos

The Taínos spoke an Arawak language, and most of them lived in the Greater Antilles islands (Cuba, Hispaniola, Porto-Rico…). Some lived on the Lesser Antilles islands.

Some lived on the Lesser Antilles islands.

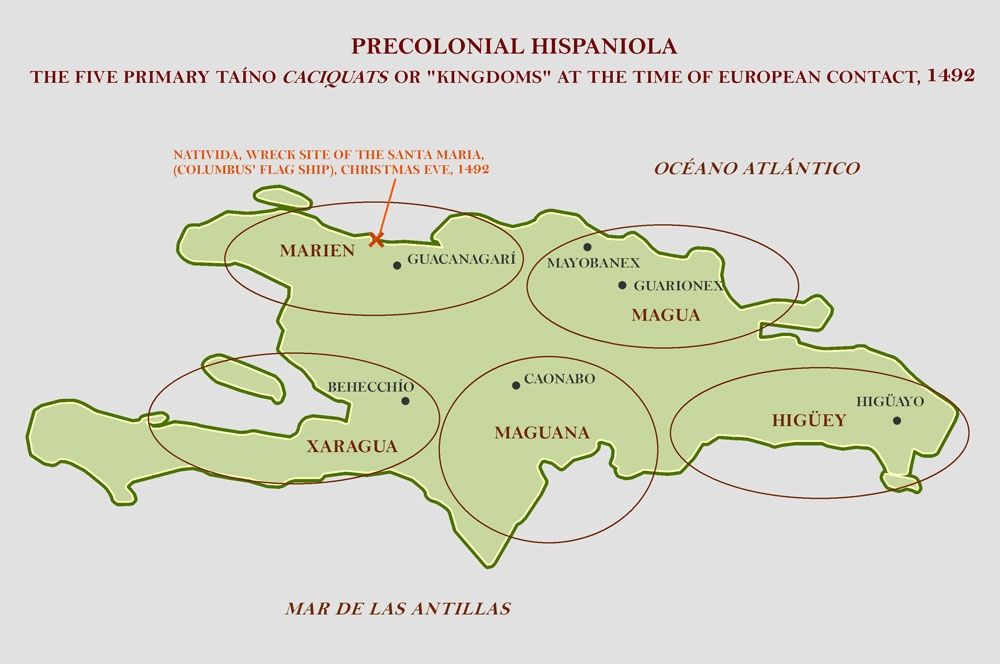

They were farmers and fishermen. Communities were generally organized around social classes, and the bigger islands like Hispaniola (actual Haiti and Dominican Republic) were split into different kingdoms lead by either male or female caciques. They were in constant conflict with the Caribs, and followed a polytheistic religion centred on the “Cemis”, divinities incarnating natural forces.

The Taínos from Hispaniola were the first Amerindians encountered by C. Columbus, on his first expedition. The arrival of the Spanish colonist meant the end of the Taínos. Slavery, war over resources, and diseases imported from the European continent decimated the population in a very short time. Although the figures are under debate, it is estimated that within 20 years, at the rise of the 16th Century, the Taíno population from Hispaniola was reduced by 90%.

Arawak language speakers from Amazonia

The speakers of Arawak languages from Amazonia follow a very different lifestyle than the early Taínos. They’re usually divided into smaller and more remote communities.

They’re usually divided into smaller and more remote communities.

Although they aren’t nomads, their lifestyle does force them to mobility and trade between the different populations of this area has always been significant.

Their history is often marked with long migrations, fusion and fission between groups. Exogamy (the practice of marrying outside one’s community) is common, including between communities who speak very different languages, thus plurilinguism is also common.

Social organization is very diverse. Some communities have one or several leaders and the elder are often regarded as the main figures when it comes to taking political decisions.

Villages are traditionally settled on the river banks, the rivers serving as transport, trade, and communication routes. They often consist in one or several “common houses” made of wooden structures covered by woven palm leaf roofs, usually sheltering several families at once.

The members of these communities are hunters/fishermen (men) and farmers (usually women). They practise slash and burn, and their agriculture is often based on tubers such as manioc, yam, and sweet potato.

They practise slash and burn, and their agriculture is often based on tubers such as manioc, yam, and sweet potato.

The remotest populations or the ones settled far enough from coasts and cities were kept relatively safe from colonisation for a long time. But with the 20th Century came the logging and mining industries (especially for gold), river pollution and urban development, missionaries and evangelists, which all contributed to perturb the traditional lifestyle of Amazonian native populations. All these cultures are threatened with extinction nowadays.

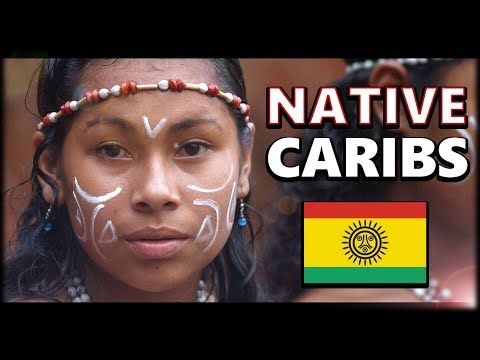

Speakers of Garifuna

The Garinagu, speakers of Garifuna, form a whole different cultural model.

They descend from an encounter between the Caribbean Amerindians (Taínos and Caribs) and the African slaves brought on the Islands’ farms. According to the official version, this encounter occurred after a slave ship crashed on Saint Vincent Island at the beginning of the 17th Century. Survivors among the slaves escaped and eventually blended with the Amerindians. Chased off their island by the English, they now live along the Caribbean coasts of Nicaragua, Honduras, and Belize.

Chased off their island by the English, they now live along the Caribbean coasts of Nicaragua, Honduras, and Belize.

Although recognized as an Arawak language, Garifuna is deeply marked by its history and bears the traces of its various influences: Carib languages, English, and English based Creole from Belize. Most speakers of Garifuna are bilingual or trilingual.

National Garifuna Council of Belize official website:

http://ngcbelize.org/content/view/3/1/

Sources

Aikhenvald, A.Y. (1999) “Arawak” in R.M.W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, (eds) The Amazonian languages, Cambridge University Press.

Please do not hesitate to contact us should you have more information on this language: [email protected]

The Dictionary of the Taino Language

The Dictionary of the Taino Language

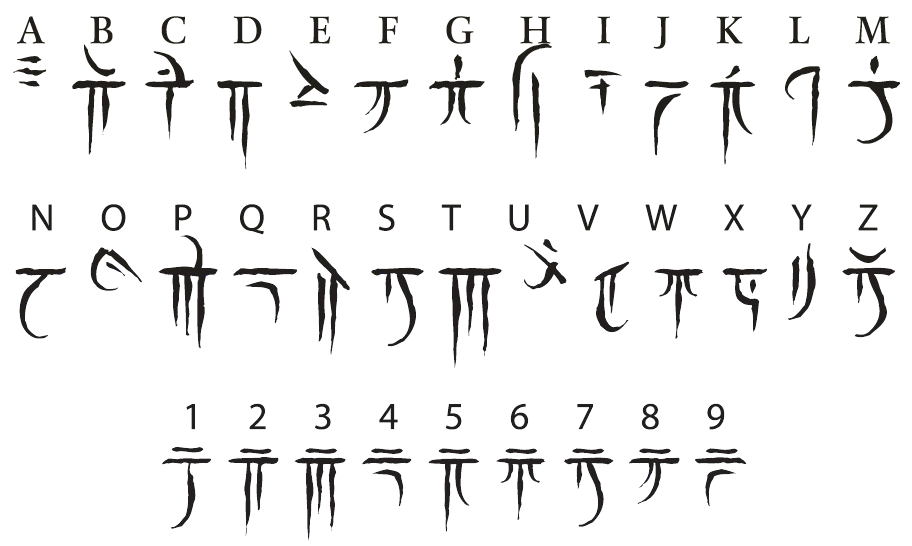

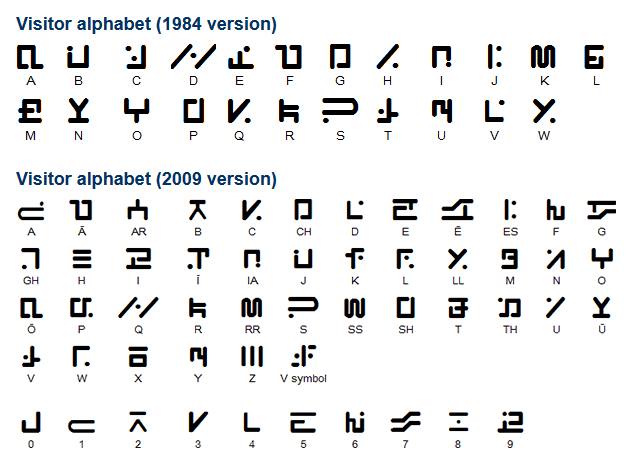

1. We have dropped the Spanish written form of “Que” and “Qui” for the

spelling of “Ke” and “Ki” in our Taino Language. The use of the double letter

The use of the double letter

“LL” and the in Spanish has also been droped from our Taino Language.

2. The Use of the Locono and other related languages of the Arawakan family

of languages will be recongized as part of the Taino Dialect language base.

3. The “X” letter has been droped from the Taino Alphabet and replaced with

the “SH” simbol for the “SH” sound, like in the word Shaman.

4. We have added 28 letters to the Taino Dialectic Alphabet, more symbols

for missing letters for nasal and gutteral sounds, will be added as we further

progress in the written form of our Taino language reconstruction.

5. Words have a deeper phonetic cultural meaning. We will attempt to break

down these word in our dictionary, so that the deeper meanings will become clearer

and give a better understanding of the Taino Language.

6. This Dictionary includes words in the Eyeri Arawak dialect that are part of

the Taino dialectic language of the Caribbean.

7. If you see this apostrophe mark [‘] it is used as an accent mark to emphasises

a letter the same way as in modern Spanish.

Notes On Lenguistic Errors In The Taino Language of Today

The “Wa” sound does not adhere to the traditional Taino “Gua” sound that was historicly

documented as part of the Taino cultural language of the Caribbean & Florida region.

The following is an example of a lenguistic Error: The Word “Guajataca” is correct, but

the word “Wajataca” is incorrect. It is noted that within the Arawakan family of dialects,

the “Wa” sound is of the language. It is also noted, that in the Taino Arawak

Dialect, the “Gua” sound, is of a Caribbean lenguistic origin. Also it is to be noted

that the word “Cuan” found in the say “Guakia Taino Cuan Yahabo” or “We the Taino Are Still

Here” and is a lenguistic error. It comes from an old Spanish origin, found in the Spanish

dictionary of today. The word Cuan means “Are” and is not of the Taino origin. It would be

It would be

correct to say “Guakia Taino Yahabo” with out the Spanish word Cuan.

8. Note, many of the personal names will not be found in the dictionary section of terms.

If not they will be under the section of “People” as these personal names

do not belong in a dictionary of terms. Some names will be found in the dicctionary

of terms as these names can be translated. An example is like the name of Anacaona or

“Golden Flower”.

9. It is to be noted that, in this new Taino dictionary, you wil

note some new words and terms. These words were not included in the

past word lists of the pre-Columbian Taino Arawak language. Our

Language is part of our people’s living cultural, thus a living

language of a people will forever be in development.

Copyright | 2020 | taino-tribe.org

Taino (people) | it’s… What is the Taíno (people)?

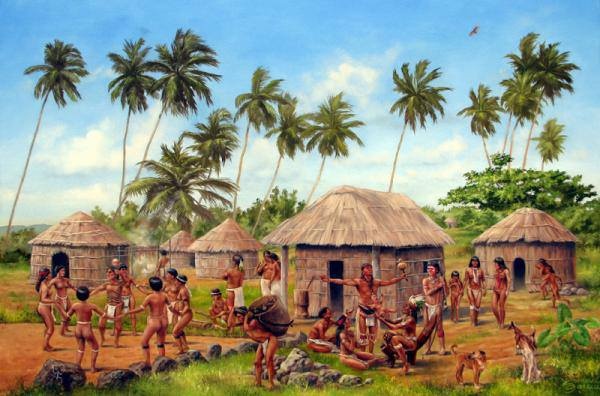

Reconstruction of the Taino village in Cuba

Taíno (Spanish: Taíno ) is a pre-Columbian indigenous population of the Bahamas and the Greater Antilles, which include Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico and Jamaica.

It was previously believed that the sailors Taíno are related to the Arawaks of South America. Recent discoveries suggest a more likely origin for Taíno from the Andean tribes, in particular from colla . Their language belongs to the Maipur languages spoken in South America and the Caribbean, which are part of the Arawakan language family. The Bahamian Taíno were called the Lucayans (then the Bahamas were known as the Lucayan Islands).

Some researchers distinguish between Neo-Taino Cuba, Lucayans Bahamas, Jamaica and to a lesser extent Haiti and Quisqueia ( Quisqueya ) (approximately the territory of the Dominican Republic) and true Taíno Boriquen ( Boriquen ) (Puerto Rico). They consider this distinction important because the Neo-Taino are more culturally diverse and socially and ethnically heterogeneous than the original Taino .

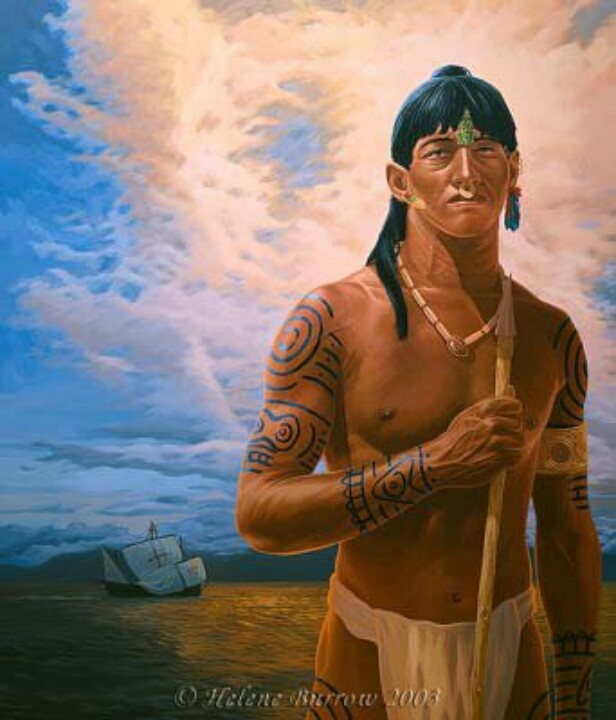

At the time of Columbus’s arrival in 1492, there were five “kingdoms” or territories in Hispaniola, each headed by a cacique (chief) to whom tribute was paid. During the Spanish conquests, the largest Taino settlements numbered up to 3 thousand people or more.

During the Spanish conquests, the largest Taino settlements numbered up to 3 thousand people or more.

Historically the Taíno were neighbors and rivals of the Caribs, another group of tribes originating from South America who mainly inhabited the Lesser Antilles. Much research has been devoted to the relationship between these two groups.

Tainos are said to have died out in the 17th century from imported diseases and forced assimilation into the plantation economy introduced by Spain in their Caribbean colonies, followed by the importation of slaves from Africa. However, the main reason for the disappearance of this culture was the massacre carried out by the Spaniards. It is claimed that there was a significant miscegenation, and that a few Indian pueblos survived until the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first landed in the Bahamas, Cuba and Hispaniola in 1492, and then to Puerto Rico, did not bring women with them. They entered into a civil marriage with women Taino . From these marriages, mestizo children were born. [1]

From these marriages, mestizo children were born. [1]

Contents

|

Origin

There is a point of view that Taino came to the Caribbean through Guyana and Venezuela to Trinidad, subsequently spreading north and west throughout the Antilles around 1000 BC. e., after the migration of the Siboneans. However, recent discoveries have shown that a more accurate hypothesis is their proximity to the ancient tribe colla in the Andes. The Taino traded extensively with other tribes in Florida and Central America, where they sometimes had outposts, although there were no permanent settlements. The Caribs followed 90,007 Taíno 90,008 to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

The Caribs followed 90,007 Taíno 90,008 to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

Caribs originate from the population of the South American continent. Caribs are sometimes referred to as Arawak, although linguistic similarities may have developed over centuries of close contact between these groups, both before and after the migration to the Caribbean Islands (see below). In any case, there are enough differences in the socio-political organization between the Arawaks and the Caribs to classify them as different peoples.

Terminology

Acquaintance of Europeans with Taíno occurred in stages as they colonized the Caribbean. Columbus called the inhabitants of the northern islands Taino , which in Arawak means “friendly people” in contrast to the hostile Caribs. This name covered all the insular Taino , which in the Lesser Antilles were often referred to by the name of a particular tribe Taino .

This name covered all the insular Taino , which in the Lesser Antilles were often referred to by the name of a particular tribe Taino .

Other Europeans arriving in South America named the same ethnic group Arawakami according to the Arawak word for cassava (tapioca) flour, which was the staple food of this ethnic group. Over time, the ethnic group began to be called Arawak (eng. Arawak ), and the language was Arawak. Later it turned out that the culture and language, as well as the ethnicity of the people known as Arawak and Taino, were the same, and often among them were distinguished mainland Taino or mainland Arawak living in Guyana and Venezuela, island Taino or island the Arawaks, who inhabit the Windward Islands; and simply the Taíno, who live in the Greater Antilles and the Leeward Islands.

For a long time travelers, historians, linguists, anthropologists used these terms mixed. The word Taino sometimes denoted only the tribes of the Greater Antilles, sometimes they also included the tribes of the Bahamas, sometimes the Leeward Islands or all of them together, with the exception of the tribes of Puerto Rico and the Leeward Islands. The 90,007 Insular Taíno 90,008 included residents of only the Windward Islands, only the population of the northern part of the Caribbean, or residents of all islands. Currently, modern historians, linguists and anthropologists believe that the term “Taino” should refer to all the Taino / Arawak tribes, except for the Caribs. Neither anthropologists nor historians consider the Caribs to be the same ethnic group, although linguists still debate whether the Caribbean language is an Arawakan dialect or a Creole language, or perhaps a separate language, with Arawakan pidgin often used in communication.

The 90,007 Insular Taíno 90,008 included residents of only the Windward Islands, only the population of the northern part of the Caribbean, or residents of all islands. Currently, modern historians, linguists and anthropologists believe that the term “Taino” should refer to all the Taino / Arawak tribes, except for the Caribs. Neither anthropologists nor historians consider the Caribs to be the same ethnic group, although linguists still debate whether the Caribbean language is an Arawakan dialect or a Creole language, or perhaps a separate language, with Arawakan pidgin often used in communication.

Culture and lifestyle

In the middle of the sample settlement Taino ( yukayek ) there was a flat area ( batei ) where social events took place: games, celebrations and public ceremonies. The site was surrounded by houses. Taino played a ceremonial ball game called “batu”. Teams of players (from 10 to 30 people each) participated in the game. The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

The Taino society was divided into four main groups:

- set (ordinary people)

- nitaino (junior chiefs)

- bohics (priests/physicians)

- caciques (chiefs)

Often the main population lived in large round huts ( bohio ) built from wooden poles, woven straw mats and palm leaves. These huts housed 10-15 families. The caciques with their families lived in rectangular buildings ( cane ) of a similar design with a wooden porch. From the furniture in the house there were cotton hammocks ( hamaka ), palm mats, wooden chairs ( duyo ) with wicker seats, platforms, children’s cradles. Some tribes Taino practiced polygamy. Men could have 2 or 3 wives, sometimes women had 2 or 3 husbands, and caciques had up to 30 wives.

Taino were mainly engaged in agriculture, as well as fishing and hunting. A common hairstyle was bangs in front and long hair in the back. Sometimes they wore gold jewelry, painted themselves, adorned themselves with shells. Sometimes men Taino wore short skirts. Taíno women wore skirts ( nagua ) after marriage.

A common hairstyle was bangs in front and long hair in the back. Sometimes they wore gold jewelry, painted themselves, adorned themselves with shells. Sometimes men Taino wore short skirts. Taíno women wore skirts ( nagua ) after marriage.

Taíno spoke a variety of Arawakan and used the following words: barbacoa ( barbecue ), hamaka ( hammock ), canoa ( canoe ), tabaco ( tabac ) and huracan ( 90 07 ), which 90 entered Spanish, English and Russian.

Nutrition and agriculture

Power base Taino were vegetables, meat and fish. There was never a lot of big game on the islands, small animals were eaten: rodents, bats, earthworms, ducks, turtles, birds.

Taino communities that lived far from the coast relied more on agriculture. They cultivated their crops on konuko , large ridges that were compacted with leaves to prevent erosion and planted with different types of plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

Technology

The Taino made extensive use of cotton, hemp and palm trees for making fishing nets and ropes. Their hollowed-out canoes (canoas) varied in size and could carry from 2 to 150 people. A medium-sized canoa held about 15 to 20 people. The Taíno used bows and arrows and sometimes smeared arrowheads of various kinds with poisons. They used spears for fishing. For military purposes, they used wooden combat batons (clubs), which they called “macana” ( macana ) were about three centimeters thick and resembled cocomacaque .

Religion

The Taíno revered all forms of life and recognized the importance of thanksgiving, as well as honoring ancestors and spirits, whom they called seven or zemi . [2] Many stone images seven have survived. Some stalagmites in the Dondon caves are hewn in the form of seven . Seven sometimes had the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, caimans, as well as various abstract and humanoid faces.

[2] Many stone images seven have survived. Some stalagmites in the Dondon caves are hewn in the form of seven . Seven sometimes had the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, caimans, as well as various abstract and humanoid faces.

Some of the seven carved include a small table or tray on which is believed to have been placed a hallucinogenic concoction, the so-called cohoba, made from the beans of a species of the Anadenanthera tree (Anadenanthera). Such trays were found along with ornamented breathing tubes.

During some rites the Taíno vomited with a swallowing stick. This was done with the aim of cleansing the body of impurities, both literal physical and symbolic spiritual cleansing. After the ritual of offering bread, first to the spirits seven , then the cacique, and then the ordinary members of the community, the epic song of the village was performed to the accompaniment of the maraka and other musical instruments.

Taíno oral tradition explains how the sun and moon came out of the caves. Another legend tells that people once lived in caves and came out of them only at night, because it was believed that the Sun would change them. The origin of the oceans is described in the legend of a giant flood that happened when a father killed his son (who was about to kill his father) and then put his bones in a gourd or calabash bottle. Then the bones turned into fish, the bottle broke and all the waters of the world poured out of it.

The supreme deity was called “yukahu” ( Yucahú ), meaning “white yuca” or “spirit of yuca”, as the yuca was the main source of food for the Taíno and was revered as such.

Some anthropologists argue that some or all of the Petwo Voodoo rituals may be traced back to the Taíno religion.

Columbus and Taino

Christopher Columbus and his crew landed in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492, becoming the first Europeans to see the Taíno people. It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually covered all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually covered all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

There are discussions about the number of Tainos who inhabited Haiti when Columbus landed there in 1492. The Catholic priest and historian of that time, Bartolome de Las Casas, wrote (1561) in his multi-volume History of the Indies:

- “ This island was inhabited by 60,000 people [when I arrived in 1508], including Indians; thus from 1494 to 1508 more than three million people died from war, slavery and mines. Who in future generations will believe this? ”

Today, a number of historians suggest that Las Casas’ figures for the pre-European population of the Taíno are exaggerated, and that a figure closer to one million seems more likely. Estimates of the Taino population vary greatly, ranging from a few hundred thousand to 8 million. They were not immune from European diseases, especially smallpox, but many of them were driven to their graves by overwork in the mines and fields, slaughtered in the brutal suppression of rebellions, or committed suicide to escape their cruel new masters. According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

During Columbus’s second voyage, he began demanding tribute from the Tainos in Haiti. Each Taino adult over the age of 14 had to give a certain amount of gold. At an early stage, the conquests, in case of non-payment of tribute, either maimed him or executed him. Later, for fear of losing their labor force, they were ordered to hand in 11 kg of cotton each. This fear also led to a demand for a remission called “ encomienda “. Under this system, the Taíno had to work for the Spaniard who owned the land for most of the year, leaving them little time to attend to the affairs of their community.

Colonization resistance

Taino heritage today

Many people still claim to be Taino descendants, especially among Puerto Ricans, both on the island itself and in the US mainland. People who claim to be descended from the Taino are actively trying to gain recognition for their tribe. More recently, a number of Taíno organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taíno People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” ( The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico) ). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

More recently, a number of Taíno organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taíno People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” ( The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico) ). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

Lambda Sigma Upsilon, Latino Fraternity, Incorporated ) made the Taíno Indians their cultural icon. [4]

See also

- Indians

- Indian Genocide

Notes

- ↑ Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-Afro-European People and Culture on Hispaniola .

- ↑ (meaning)

- ↑ Indigenous resurgence in the contemporary Caribbean

- ↑ Lambda Sigma Upsilon

Literature

- Guitar, Lynne.

2000. “Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo – Afro – European People and Culture on Hispaniola.” KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology , 1(1): 1-17 http://www.kacike.org/LynneGuitar.html

2000. “Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo – Afro – European People and Culture on Hispaniola.” KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology , 1(1): 1-17 http://www.kacike.org/LynneGuitar.html - United Confederation of Taino People http://www.uctp.org/

- The Jatibonicù Taino Tribal Band of New Jersey (A Tribal Government Affairs website)

- The Jatibonicù Taino Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico Tribal Government website)

- Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean: Amerindian Survival and Revival . Edited by Maximilian C. Forte. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2006. http://www.centrelink.org/resurgence/index.html

- DeRLAS. Some important research contributions of Genetics to the study of Population History and Anthropology in Puerto Rico. Newark, Delaware: Delaware Review of Latin American Studies . August 15, 2000.

- The Role of Cohoba in Taino Shamanism Constantino M.

Torres in Eleusis No. 1 (1998)

Torres in Eleusis No. 1 (1998) - Shamanic Inebriants in South American Archaeology: Recent lnvestigations Constantino M. Torres in Eleusis No. 5 (2001)

Links

- Dominican Republic – History of the Taíno in Hispaniola

- Island Thresholds , an interactive page for the Peabody Essex Museum showcasing original work by Caribbean artists.

Taíno (people) | it’s… What is the Taíno (people)?

Reconstruction of the Taíno village in Cuba

Taíno (Spanish: Taíno ) is a pre-Columbian indigenous population of the Bahamas and the Greater Antilles, which include Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico and Jamaica.

It was previously believed that the sailors Taíno are related to the Arawaks of South America. Recent discoveries indicate more likely the origin of Taíno from the Andean tribes, in particular from coll . Their language belongs to the Maipur languages spoken in South America and the Caribbean, which are part of the Arawakan language family. The Bahamian Taíno were called the Lucayans (then the Bahamas were known as the Lucayan Islands).

The Bahamian Taíno were called the Lucayans (then the Bahamas were known as the Lucayan Islands).

Some researchers distinguish between Neo-Taino Cuba, Lucayans Bahamas, Jamaica and to a lesser extent Haiti and Quisqueya ( Quisqueya ) (approximately the territory of the Dominican Republic) and the true Taino Boriquena ( Boriquen ) (Puerto Rico). They consider this distinction important because the Neo-Taino are more culturally diverse and socially and ethnically heterogeneous than the original Taino .

At the time of Columbus’s arrival in 1492, there were five “kingdoms” or territories in Hispaniola, each headed by a cacique (chief) to whom tribute was paid. During the Spanish conquests, the largest Taino settlements numbered up to 3 thousand people or more.

Historically the Taíno were neighbors and rivals of the Caribs, another group of tribes originating from South America who mainly inhabited the Lesser Antilles. Much research has been devoted to the relationship between these two groups.

Much research has been devoted to the relationship between these two groups.

Tainos are said to have died out in the 17th century from imported diseases and forced assimilation into the plantation economy introduced by Spain in their Caribbean colonies, followed by the importation of slaves from Africa. However, the main reason for the disappearance of this culture was the massacre carried out by the Spaniards. It is claimed that there was a significant miscegenation, and that a few Indian pueblos survived until the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first landed in the Bahamas, Cuba and Hispaniola in 1492, and then to Puerto Rico, did not bring women with them. They entered into a civil marriage with women Taino . From these marriages, mestizo children were born. [1]

Contents

|

Origin

There is a point of view that Taino came to the Caribbean through Guyana and Venezuela to Trinidad, subsequently spreading north and west throughout the Antilles around 1000 BC. e., after the migration of the Siboneans. However, recent discoveries have shown that a more accurate hypothesis is their proximity to the ancient tribe colla in the Andes. The Taino traded extensively with other tribes in Florida and Central America, where they sometimes had outposts, although there were no permanent settlements. The Caribs followed 90,007 Taíno 90,008 to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

e., after the migration of the Siboneans. However, recent discoveries have shown that a more accurate hypothesis is their proximity to the ancient tribe colla in the Andes. The Taino traded extensively with other tribes in Florida and Central America, where they sometimes had outposts, although there were no permanent settlements. The Caribs followed 90,007 Taíno 90,008 to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

Caribs originate from the population of the South American continent. Caribs are sometimes referred to as Arawak, although linguistic similarities may have developed over centuries of close contact between these groups, both before and after the migration to the Caribbean Islands (see below). In any case, there are enough differences in the socio-political organization between the Arawaks and the Caribs to classify them as different peoples.

Terminology

Acquaintance of Europeans with Taíno occurred in stages as they colonized the Caribbean. Columbus called the inhabitants of the northern islands Taino , which in Arawak means “friendly people” in contrast to the hostile Caribs. This name covered all the insular Taino , which in the Lesser Antilles were often referred to by the name of a particular tribe Taino .

Other Europeans arriving in South America named the same ethnic group Arawakami according to the Arawak word for cassava (tapioca) flour, which was the staple food of this ethnic group. Over time, the ethnic group began to be called Arawak (eng. Arawak ), and the language was Arawak. Later it turned out that the culture and language, as well as the ethnicity of the people known as Arawak and Taino, were the same, and often among them were distinguished mainland Taino or mainland Arawak living in Guyana and Venezuela, island Taino or island the Arawaks, who inhabit the Windward Islands; and simply the Taíno, who live in the Greater Antilles and the Leeward Islands.

For a long time travelers, historians, linguists, anthropologists used these terms mixed. The word Taino sometimes denoted only the tribes of the Greater Antilles, sometimes they also included the tribes of the Bahamas, sometimes the Leeward Islands or all of them together, with the exception of the tribes of Puerto Rico and the Leeward Islands. The 90,007 Insular Taíno 90,008 included residents of only the Windward Islands, only the population of the northern part of the Caribbean, or residents of all islands. Currently, modern historians, linguists and anthropologists believe that the term “Taino” should refer to all the Taino / Arawak tribes, except for the Caribs. Neither anthropologists nor historians consider the Caribs to be the same ethnic group, although linguists still debate whether the Caribbean language is an Arawakan dialect or a Creole language, or perhaps a separate language, with Arawakan pidgin often used in communication.

Culture and lifestyle

In the middle of the sample settlement Taino ( yukayek ) there was a flat area ( batei ) where social events took place: games, celebrations and public ceremonies. The site was surrounded by houses. Taino played a ceremonial ball game called “batu”. Teams of players (from 10 to 30 people each) participated in the game. The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

The site was surrounded by houses. Taino played a ceremonial ball game called “batu”. Teams of players (from 10 to 30 people each) participated in the game. The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

The Taino society was divided into four main groups:

- set (ordinary people)

- nitaino (junior chiefs)

- bohics (priests/physicians)

- caciques (chiefs)

Often the main population lived in large round huts ( bohio ) built from wooden poles, woven straw mats and palm leaves. These huts housed 10-15 families. The caciques with their families lived in rectangular buildings ( cane ) of a similar design with a wooden porch. From the furniture in the house there were cotton hammocks ( hamaka ), palm mats, wooden chairs ( duyo ) with wicker seats, platforms, children’s cradles. Some tribes Taino practiced polygamy. Men could have 2 or 3 wives, sometimes women had 2 or 3 husbands, and caciques had up to 30 wives.

Men could have 2 or 3 wives, sometimes women had 2 or 3 husbands, and caciques had up to 30 wives.

Taino were mainly engaged in agriculture, as well as fishing and hunting. A common hairstyle was bangs in front and long hair in the back. Sometimes they wore gold jewelry, painted themselves, adorned themselves with shells. Sometimes men Taino wore short skirts. Taíno women wore skirts ( nagua ) after marriage.

Taíno spoke a variety of Arawakan and used the following words: barbacoa ( barbecue ), hamaka ( hammock ), canoa ( canoe ), tabaco ( tabac ) and huracan ( 90 07 ), which 90 entered Spanish, English and Russian.

Nutrition and agriculture

Power base Taino were vegetables, meat and fish. There was never a lot of big game on the islands, small animals were eaten: rodents, bats, earthworms, ducks, turtles, birds.

Taino communities that lived far from the coast relied more on agriculture. They cultivated their crops on konuko , large ridges that were compacted with leaves to prevent erosion and planted with different types of plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

They cultivated their crops on konuko , large ridges that were compacted with leaves to prevent erosion and planted with different types of plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

Technology

The Taino made extensive use of cotton, hemp and palm trees for making fishing nets and ropes. Their hollowed-out canoes (canoas) varied in size and could carry from 2 to 150 people. A medium-sized canoa held about 15 to 20 people. The Taíno used bows and arrows and sometimes smeared arrowheads of various kinds with poisons. They used spears for fishing. For military purposes, they used wooden combat batons (clubs), which they called “macana” ( macana ) were about three centimeters thick and resembled cocomacaque .

Religion

The Taíno revered all forms of life and recognized the importance of thanksgiving, as well as honoring ancestors and spirits, whom they called seven or zemi . [2] Many stone images seven have survived. Some stalagmites in the Dondon caves are hewn in the form of seven . Seven sometimes had the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, caimans, as well as various abstract and humanoid faces.

Some of the seven carved include a small table or tray on which is believed to have been placed a hallucinogenic concoction, the so-called cohoba, made from the beans of a species of the Anadenanthera tree (Anadenanthera). Such trays were found along with ornamented breathing tubes.

During some rites the Taíno vomited with a swallowing stick. This was done with the aim of cleansing the body of impurities, both literal physical and symbolic spiritual cleansing. After the ritual of offering bread, first to the spirits seven , then the cacique, and then the ordinary members of the community, the epic song of the village was performed to the accompaniment of the maraka and other musical instruments.

Taíno oral tradition explains how the sun and moon came out of the caves. Another legend tells that people once lived in caves and came out of them only at night, because it was believed that the Sun would change them. The origin of the oceans is described in the legend of a giant flood that happened when a father killed his son (who was about to kill his father) and then put his bones in a gourd or calabash bottle. Then the bones turned into fish, the bottle broke and all the waters of the world poured out of it.

The supreme deity was called “yukahu” ( Yucahú ), meaning “white yuca” or “spirit of yuca”, as the yuca was the main source of food for the Taíno and was revered as such.

Some anthropologists argue that some or all of the Petwo Voodoo rituals may be traced back to the Taíno religion.

Columbus and Taino

Christopher Columbus and his crew landed in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492, becoming the first Europeans to see the Taíno people. It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually covered all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually covered all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

There are discussions about the number of Tainos who inhabited Haiti when Columbus landed there in 1492. The Catholic priest and historian of that time, Bartolome de Las Casas, wrote (1561) in his multi-volume History of the Indies:

- “ This island was inhabited by 60,000 people [when I arrived in 1508], including Indians; thus from 1494 to 1508 more than three million people died from war, slavery and mines. Who in future generations will believe this? ”

Today, a number of historians suggest that Las Casas’ figures for the pre-European population of the Taíno are exaggerated, and that a figure closer to one million seems more likely. Estimates of the Taino population vary greatly, ranging from a few hundred thousand to 8 million. They were not immune from European diseases, especially smallpox, but many of them were driven to their graves by overwork in the mines and fields, slaughtered in the brutal suppression of rebellions, or committed suicide to escape their cruel new masters. According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

During Columbus’s second voyage, he began demanding tribute from the Tainos in Haiti. Each Taino adult over the age of 14 had to give a certain amount of gold. At an early stage, the conquests, in case of non-payment of tribute, either maimed him or executed him. Later, for fear of losing their labor force, they were ordered to hand in 11 kg of cotton each. This fear also led to a demand for a remission called “ encomienda “. Under this system, the Taíno had to work for the Spaniard who owned the land for most of the year, leaving them little time to attend to the affairs of their community.

Colonization resistance

Taino heritage today

Many people still claim to be Taino descendants, especially among Puerto Ricans, both on the island itself and in the US mainland. People who claim to be descended from the Taino are actively trying to gain recognition for their tribe. More recently, a number of Taíno organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taíno People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” ( The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico) ). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

More recently, a number of Taíno organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taíno People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” ( The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico) ). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

Lambda Sigma Upsilon, Latino Fraternity, Incorporated ) made the Taíno Indians their cultural icon. [4]

See also

- Indians

- Indian Genocide

Notes

- ↑ Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-Afro-European People and Culture on Hispaniola .

- ↑ (meaning)

- ↑ Indigenous resurgence in the contemporary Caribbean

- ↑ Lambda Sigma Upsilon

Literature

- Guitar, Lynne.

2000. “Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo – Afro – European People and Culture on Hispaniola.” KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology , 1(1): 1-17 http://www.kacike.org/LynneGuitar.html

2000. “Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo – Afro – European People and Culture on Hispaniola.” KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology , 1(1): 1-17 http://www.kacike.org/LynneGuitar.html Torres in Eleusis No. 1 (1998)

Torres in Eleusis No. 1 (1998)