Borinquen meaning: Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Borinqueneers Day and the Korean War in Puerto Rican History and Memory

About the author

Dr. Harry Franqui-Rivera is an Associate Professor of History at Bloomfield College, N.J. He is a prolific published author, documentary producer, public intellectual, cultural critic, blogger, political analyst, and NBC, Latino Rebels, and HuffPost contributor. His work has been featured in national and international media outlets, Telemundo, the New York Times, and NPR. His latest book, Soldiers of the Nation: Military Service and Modern Puerto Rico, (2018) has been widely praised. His next book, Fighting on Two Fronts: The Ordeal of the Puerto Rican Soldier during the Korean War will be published by Centro Press. He served in the U.S. Army Reserve and National Guard for over a decade and currently serves in several academic, advocacy and policy boards such as the National Puerto Rican Agenda.

Borinqueneers Day and the Korean War in Puerto Rican History and Memory

June 25, 2020 marked the 70th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean War. No conflict has been as impactful and transformative for Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans as the Korean War. In slightly over three years of fighting (June 25, 1950 to July 27, 1953) some 61,000 Puerto Ricans served in the U.S. Army. They suffered 3,540 casualties of which 747 were killed in action (KIA) or died of their wounds. By comparison, during World War II, some 65,000 Puerto Ricans served, of which 368 lost their lives in combat, training, and accidents. Although WWII officially ended on September 2, 1945, this number includes those who served between November 20, 1940 to March 21, 1947. Thus, the number of Puerto Ricans serving in the biggest conflict in history and the longest war in American history to that point (WWII), is about the same of that of the Korean War where the fighting was limited to the Korean peninsula.

No conflict has been as impactful and transformative for Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans as the Korean War. In slightly over three years of fighting (June 25, 1950 to July 27, 1953) some 61,000 Puerto Ricans served in the U.S. Army. They suffered 3,540 casualties of which 747 were killed in action (KIA) or died of their wounds. By comparison, during World War II, some 65,000 Puerto Ricans served, of which 368 lost their lives in combat, training, and accidents. Although WWII officially ended on September 2, 1945, this number includes those who served between November 20, 1940 to March 21, 1947. Thus, the number of Puerto Ricans serving in the biggest conflict in history and the longest war in American history to that point (WWII), is about the same of that of the Korean War where the fighting was limited to the Korean peninsula.

The numbers also tell us about the nature of Puerto Rican involvement in both wars. In a regional conflict (although of global repercussion) like the Korean War, the number of Puerto Rican fatal casualties was twice as much as in World War II. This is the case because the Korean War was the first instance in which large numbers of Puerto Ricans were sent into combat. This is a most relevant issue and part of what makes the Korean War so impactful in Puerto Rican history and society, both state and island-side.

This is the case because the Korean War was the first instance in which large numbers of Puerto Ricans were sent into combat. This is a most relevant issue and part of what makes the Korean War so impactful in Puerto Rican history and society, both state and island-side.

The nature of Puerto Rican military service in Korea is also different than that of the Vietnam War. During that conflict, in which the United States had some kind of involvement from November 1, 1955 to April 30, 1975, official records show some 48,000to 60,000 Puerto Ricans serving, and 345 to 450 killed in action (KIA) or dying of their wounds or in captivity. The numbers’ discrepancy is rooted in the difficulty to estimate those Puerto Ricans who were drafted or volunteered while state-side. During the Vietnam War, Puerto Ricans fought as combat troops since the beginning of it. Yet, their participation numbers (when state-side estimates are included) hover around that of the Korean War, and the fatal casualty ratio still about half of the Korean War. The casualty rate was lower in Vietnam (compared to Korea) because the Puerto Ricans were spread throughout all the branches of the armed forces and performing all kinds of tasks or military occupational skill (MOS). That was not the case in Korea in which most of the Puerto Ricans who served did so as infantry men and as part of the 65th United States Infantry Regiment. The history of this regiment is another element making the Korean War so different from other conflicts in Puerto Rican history.

The casualty rate was lower in Vietnam (compared to Korea) because the Puerto Ricans were spread throughout all the branches of the armed forces and performing all kinds of tasks or military occupational skill (MOS). That was not the case in Korea in which most of the Puerto Ricans who served did so as infantry men and as part of the 65th United States Infantry Regiment. The history of this regiment is another element making the Korean War so different from other conflicts in Puerto Rican history.

Borinqueneers boarding a transport ship to complete a voyage from San Juan to Pusan, Korea. 1950

The 65th U.S. Army Regiment of Infantry, the Borinqueneers

The 65th U.S. Infantry Regiment, also known as the “el sesenta y cinco” and its men as the “Borinqueneers,” was a distinctively Puerto Rican outfit. “Borinqueneers” is both a Spanish and English transliteration of Boriken- the Arawak or Taino- indigenous name for Puerto Rico- the three first syllables are meant to be read in Spanish and the last one in English. The unit’s nickname in itself tells you much about the role of this regiment in Puerto Rican history. They fought in Korea from 1950 to 1953 as part of the U.S. Army 3rd Infantry Division.

The unit’s nickname in itself tells you much about the role of this regiment in Puerto Rican history. They fought in Korea from 1950 to 1953 as part of the U.S. Army 3rd Infantry Division.

The 65th’s enlisted men, non-commissioned officers (NCOs), and some of its junior officers hailed from the Island, although the regiment also had many officers who were continental white Americans, particularly in senior positions. The 65th was part of the active United States Army. It was not a reserve component of a National Guard unit. The fact that it was a segregated regiment for Puerto Rican enlisted men and led mostly by non-Puerto Rican whites, made its rank-and-file colonial troops, and the only “Hispanic” segregated unit in the United States Armed Forces. For most of its history (which dates back to 1899), the 65th Infantry was a garrison unit. Intended for service on the island, regarded as unfit for combat and overseas deployment, and colloquially called a “Rum & Coke” outfit, the 65th was kept far from combat until the Korean War, when the U. S. Army decided to use the Borinqueneers as first-line combat troops.

S. Army decided to use the Borinqueneers as first-line combat troops.

The Korean War

The decision to send the Borinqueneers as combat troops was influenced by several factors. Chief among them was Executive Order 9981, signed in 1948 by President Harry Truman, which paved the way for the desegregation of the armed forces. Up to the Korean War, institutional racism had kept Puerto Rican units from the battlefield- just like most African-American units- they were simply not trusted in battle because of their race and culture- as many official documents form the war department evidence.

On October 12, 1950, Puerto Ricans learned that the 65th was fighting in Korea. The island’s newspapers were full of stories and pictures of the soldiers and the ceremonies held previous to their departure. Island-wide, the people of Puerto Rico joined to support the 65th throughout the war. Governor Luis Muñoz Marín often made reference to the men of the 65th in his speeches.:origin()/pre13/0145/th/pre/i/2015/125/b/3/tg_caption___the_best_by_ugu_d_deviant-d8s95tp.png) The crest of the regiment was painted in public buses and train cars.

The crest of the regiment was painted in public buses and train cars.

Plazas and avenues were named to honor the regiment. Returning soldiers, especially the wounded, were received as heroes and treated to public receptions by government officials. Governor Muñoz Marín himself, attended the burials of the fallen and sent his recorded speeches to the troops in Korea. In the early days of the war, a day did not pass in which the island’s press didn’t write about the Puerto Rican soldiers. Soldiers were paid to endorse local products, from non-alcoholic malt beverages to powder milk. Some of the soldiers’ exploits even found their way to comic strips. The 65th had become a national icon on the island and among the growing Puerto Rican communities in the mainland.

Most of the men of the 65th Infantry could not have been prouder to belong to a regiment with such strong ties to Puerto Rico, and the island’s civilian population shared that pride. What were the reasons for such sentiments? Most of the 65th’s enlisted men had entered the military to escape the island’s economic problems. Once they joined the regiment, however, they remained in uniform for something besides steady pay. Many Borinqueneers who served during World War II reenlisted during the Korean War. Furthermore, even after the Korean War had become a bloody stalemate and the Puerto Rican press began to publish long casualty lists, the recruiting stations in Puerto Rico never lacked for enthusiastic volunteers. The daily news in the local press- detailing the heroics of the Borinqueneers, led to many men enlisting hoping to be assigned to the 65th, the Puerto Rican regiment. Many Puerto Ricans did not serve with the 65th, even after volunteering. Of the 43,434 men who served with the 65th, 39,591 or roughly 91% were volunteers. The numbers of Puerto Ricans volunteering to fight in this war led to recruitment centers in Puerto Rico rarely having to use the draft.

Once they joined the regiment, however, they remained in uniform for something besides steady pay. Many Borinqueneers who served during World War II reenlisted during the Korean War. Furthermore, even after the Korean War had become a bloody stalemate and the Puerto Rican press began to publish long casualty lists, the recruiting stations in Puerto Rico never lacked for enthusiastic volunteers. The daily news in the local press- detailing the heroics of the Borinqueneers, led to many men enlisting hoping to be assigned to the 65th, the Puerto Rican regiment. Many Puerto Ricans did not serve with the 65th, even after volunteering. Of the 43,434 men who served with the 65th, 39,591 or roughly 91% were volunteers. The numbers of Puerto Ricans volunteering to fight in this war led to recruitment centers in Puerto Rico rarely having to use the draft.

The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Estado Libre Asociado) is presented to Colonel César Cordero, Commanding Officer, 65th Infantry, and Major Silvestre Ortiz, Adjutant, 65th. 1952. Image, U.S. Army Signal Corps. In the fall of 1952, Puerto Rican flags would be carried by leading elements of the 65th Infantry during attacks. The flag and appeals to national pride and unity helped the Puerto Rican soldiers overcome shortcomings such as inadequate training, a language and cultural barrier, and deficient leadership.

1952. Image, U.S. Army Signal Corps. In the fall of 1952, Puerto Rican flags would be carried by leading elements of the 65th Infantry during attacks. The flag and appeals to national pride and unity helped the Puerto Rican soldiers overcome shortcomings such as inadequate training, a language and cultural barrier, and deficient leadership.

The Meaning of the Borinqueneers’ Sacrifice for Puerto Rico and the Growing Diaspora

The press and Puerto Rican politicians shared much of the responsibility for their people’s willingness to go to war. These opinion-makers heralded the Borinqueneers as heroes, even before they reached Korea. The press, the politicians, elected officials, and the private sector praised “our boys fighting alongside the United Nations to defend world freedom and democracy.” In addition, the press talked about the experience of the 65th as a possible catalyst for getting rid of the “old man, and for forging a modern Puerto Rican nationality. ” These same articles also praised the role of the Borinqueneers in abolishing Puerto Ricans’ inferiority complex, “the byproduct of hundreds of years of colonial type regimes.” 2

” These same articles also praised the role of the Borinqueneers in abolishing Puerto Ricans’ inferiority complex, “the byproduct of hundreds of years of colonial type regimes.” 2

The Puerto Rican press, elected officials, and politicians saw in the Korean War an opportunity to prove that Puerto Ricans were politically mature, and hence ready for self-determination. By doing so, political leaders and the news media placed a heavy burden on the Puerto Rican people, who came to see it as their duty either to volunteer for military service or support the war effort. The local press and leadership, especially the Popular Democratic Party under Luis Muñoz Marín, promoted the ideals of heroism, democracy, freedom, and the war as a sort of rite of passage from which a new Puerto Rican man ready to build a modern Puerto Rico would emerge. They crafted and repeated this message to secure a more autonomous government for the island. In many ways the PPD tied its political projects to participation in the war. In a very real sense, the battle Puerto Ricans fought in Korea was a battle for equality and for many, one of decolonization. At least, that is how many of the men perceived it and how the political elites imagined it.

In a very real sense, the battle Puerto Ricans fought in Korea was a battle for equality and for many, one of decolonization. At least, that is how many of the men perceived it and how the political elites imagined it.

Borinqueneers, Sargent First Class Gilberto Acevedo on the left (San Germán) and Private First Class Aponte Martinez Santos (Lajas) Puerto Rican read a segment of the constitution of the Estado Libre Asociado, 1952. The regiment’s newspaper, The Maltese Cross, published the document by instalments so that all Puerto Rican soldiers in Korea could have the opportunity to read the new constitution. Ines Mendoza de Muñoz sent the copy to the regiment. Mendoza de Muñoz wrote in her dedication: “All Puerto Ricans are proud of their regiment in Korea,” she continued, “and we hope this constitution will “give further assurance of the freedoms you are defending so gallantly.” Pacific Stars and Stripes, Spring 1952.

Donning the uniform during the Korean War, in particular that of the U. S. Army, also had political and social value for emerging Puerto Rican communities in the Eastern seaboard of the United States. The actions of the 65th were included in the acts and annals of Congress and published in the national press. The Puerto Rican state-side local communities and press also followed the war and the Borinqueneers. They kept an eye on the returning soldiers, and in particular on the wounded and repatriated former prisoner of war (POWs) as they completed a circuit that took them from Korea to Japan, to the U.S. west coast, often to Walter Reed Military Hospital in Maryland, New York, and for most, finally to Puerto Rico.

S. Army, also had political and social value for emerging Puerto Rican communities in the Eastern seaboard of the United States. The actions of the 65th were included in the acts and annals of Congress and published in the national press. The Puerto Rican state-side local communities and press also followed the war and the Borinqueneers. They kept an eye on the returning soldiers, and in particular on the wounded and repatriated former prisoner of war (POWs) as they completed a circuit that took them from Korea to Japan, to the U.S. west coast, often to Walter Reed Military Hospital in Maryland, New York, and for most, finally to Puerto Rico.

The Puerto Rican community and press followed in detail the return of their heroes and New York City officials gave several of them the keys of the city while parades were organized to honor them. This happened at a time in which some elected city officials sought answers to “the Puerto Rican problem.” This “problem” was nothing but the constant influx of Puerto Ricans to the Eastern Seaboard as Puerto Rico transitioned from an agrarian to an industrial-based economy and relied on the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans to the mainland to alleviate unemployment. As Puerto Rican communities grew, they faced all kinds of discrimination. Highlighting the service and sacrifice of Puerto Ricans in the war became a form to engage in politics of respectability and staking a claim of belonging for sprawling Puerto Rican state-side communities. The 65th’s status as a national icon and source of pride went beyond the archipelago.

As Puerto Rican communities grew, they faced all kinds of discrimination. Highlighting the service and sacrifice of Puerto Ricans in the war became a form to engage in politics of respectability and staking a claim of belonging for sprawling Puerto Rican state-side communities. The 65th’s status as a national icon and source of pride went beyond the archipelago.

The call to arms, nevertheless, was ambiguous. The press and the governor of the island told Puerto Ricans that it was their duty- as Puerto Ricans- to defend the American nation, to which they belonged. The enthusiastic response to this call further complicated the essence of Puertoricaness. It was common for soldiers deployed in Korea to express they felt they were both Puerto Ricans and Americans. This phenomenon could be understood as a dual nationality paradigm, or as the fusing of political and cultural identities. This is one of the central issues I explore in my forthcoming book, Fighting on Two Fronts: The Experience of the Puerto Rican Soldier in the Korean War because this narrative regarding the Puerto Ricans’ identities became one of the ideological pillars for the creation of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico- the Estado Libre Asociado, which was established on July 25, 1952, and still defines the relations between the United States and the island.

“Ultimos en salir.” Last United Nations’ troops to leave the besieged port of Hugnam in North Korea after the battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Borinqueneers, Corporal Julio Guzmán and Master Sgt. Lupercio Ortíz December 24th 1950. Hugnan, Korea. When I interviewed him, Lupercio Ortíz still had a picture of himself and his assistant as they left the Hugnan beachhead. The picture was first published on Life Magazine and reprinted by the press in Puerto Rico. El Imparcial de Puerto Rico: Periódico Ilustrado, 27 December 1951.

The Borinqueneers knew they were in the spotlight and came to internalize their iconic status. On Christmas Eve of 1950, the men of the 65th, the last United Nations troops in Hungnam, were finally evacuated from the besieged port after covering the last stage of the 1st Marines division retreat from the Chosin Reservoir. Last year, an American graduate student studying in the Netherlands sent me an email in which she shared that her grandfather was one of those Marines who, when they reached American lines and safety, were met by men from Puerto Rico. She is forever grateful and so was his grandfather. (https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/centrovoices/chronicles/puerto-rican-soldiers-korean-war-battle-chosin-reservoir)

She is forever grateful and so was his grandfather. (https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/centrovoices/chronicles/puerto-rican-soldiers-korean-war-battle-chosin-reservoir)

As the 65th’s commanding officer, Colonel William W. Harris, boarded the last transport out of Hugnam, someone handed him a copy of an article from the Pacific Stars & Stripes. The article quoted Corporal Ruiz of Puerto Rico s saying:

We are proud to be part of the United Nations Forces, and we are proud of our country. We feel that too many people do not know anything about Puerto Rico; they think that we are all natives who climb trees… We are glad for the chance to fight the communists and also for the chance to put Puerto Rico on the map. It will be a great accomplishment if we can raise the prestige of our country in the eyes of the world.

Sergeant First Class, Modesto Cartagena of Cayey, home of the “Monument to the Puerto Rican Jíbaro”, earned a Distinguished Service Cross in Korea and became a national hero. Cartagena’s citation credits him with “single-handedly” knocking out enemy machine-gun emplacements on hill 206 near Yonchon, Korea, in April 1951. He destroyed the enemy positions hurling back grenades the Chinese threw at him. His citation reads that “although knocked to the ground by exploding enemy grenades,” he made three more assaults on enemy positions before being wounded by automatic weapons fire. His actions saved his whole squad. Periódico El Mundo, November 13, 1952.

Cartagena’s citation credits him with “single-handedly” knocking out enemy machine-gun emplacements on hill 206 near Yonchon, Korea, in April 1951. He destroyed the enemy positions hurling back grenades the Chinese threw at him. His citation reads that “although knocked to the ground by exploding enemy grenades,” he made three more assaults on enemy positions before being wounded by automatic weapons fire. His actions saved his whole squad. Periódico El Mundo, November 13, 1952.

The Debacle

During the first part of the Korean War Puerto Ricans soldiers were praised as heroes and champions of democracy abroad and at home. Things would change during the second half of the war and the record of the Borinqueneers would be temporarily stained. The replacement of combat-hardened troops with poorly trained—yet enthusiastic—recruits who spoke little English; an acute dearth of bilingual NCOs; and new Continental officers that did not speak Spanish (some who openly showed their disdain for Puerto Rican soldiers and officers) led to tragic events during the battles of Outpost Kelly and Jackson Heights in the autumn of 1952.

The back-to-back debacles were followed by a series of mass court martials in which eighty-seven enlisted men and one Puerto Rican officer received sentences ranging from six months to ten years imprisonment, total forfeiture of wages, and dishonorable discharges for charges varying from willful disobedience of a superior officer to cowardice before the enemy. https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/centrovoices/chronicles/honor-and-dignity-restoring-borinqueneers-historical-record

Such news was hard to swallow for the Puerto Rican public. An assembly of the soldiers’ parents drafted and sent a rather Spartan message to President Dwight Eisenhower: “PREFERIMOS VERLOS MUERTOS”. The parents’ resolution, published in the January 26, 1953 edition of the daily El Imparcial, stated; “We prefer to receive the corpses of our sons, killed heroically on the battlefields of Korea, than to have them return stained with the stigma of cowardice.”

The parents asked for their sons to have the chance to prove their accusers wrong by returning to the battlefield. Many of the sentenced soldiers wrote similar letters which were then published in the local press. In a rare display of national unity, Puerto Ricans from all walks of life, and different political affiliations and ideologies, found common ground and rallied in defense of the Borinqueneers.

Many of the sentenced soldiers wrote similar letters which were then published in the local press. In a rare display of national unity, Puerto Ricans from all walks of life, and different political affiliations and ideologies, found common ground and rallied in defense of the Borinqueneers.

They were joined by Continental officers who had served with the regiment. General J. Lawton Collins, who had visited the training camps in Puerto Rico and was very familiar with the 65th, told the House Armed Services Committee: “The Puerto Ricans have proved that they are brave and can fight as well as any other soldier when properly trained and equipped.”

Under pressure, the military agreed to conduct a review of the sentences. Few of the soldiers from the 65th had their sentences reduced. The review board found the verdicts and sentences to be correct in law and fact. But, between June and July of 1953, however, the Secretary of the Army reviewed the cases and remitted the unexecuted portions of the sentences of all but four of the accused. The soldiers who had their sentences remitted were returned to duty.

The soldiers who had their sentences remitted were returned to duty.

The Puerto Rican public was still roiling from the effects of the mass trials when more bad news reached the island. On March 4, 1953, an Army spokesman announced that the 65th would be integrated with Continental troops, and the excess Puerto Rican soldiers would be sent to other units. The 65th would cease to exist as a Puerto Rican unit.

Unidentified Puerto Rican soldiers serving with the 65th Infantry in Korea hold the Puerto Rican. Fall 1952. Photo taken by Marcelino Cruz Rodríguez, by permission from Carlos Cruz and Mirta Cruz-Home; reproduction by Noemi Fuigueroa-Soulet.

The vast majority of the Puerto Rican soldiers serving with the 65th Infantry promptly condemned the army’s decision. Pedro Martir, a member of the 65th for seventeen years, declared that he would rather lose his pension than continue to serve in an integrated 65th. Other soldiers objected to integration on the basis of unit pride and the fear of being laughed at by continental troops because of cultural differences and their difficulties with the English language. Corporal Felix Rodríguez insisted, “I think is better to fight with my own people, we understand each other.” Private First Class Antonio Martínez, a Borinqueneer from New York, commented that racial prejudice might make life hard for Puerto Ricans serving in other regiments. The regiment, however, was quickly integrated as planned.

Corporal Felix Rodríguez insisted, “I think is better to fight with my own people, we understand each other.” Private First Class Antonio Martínez, a Borinqueneer from New York, commented that racial prejudice might make life hard for Puerto Ricans serving in other regiments. The regiment, however, was quickly integrated as planned.

Eventually, the Borinqueneers’ record would be restored. In 1954, the 65th Infantry returned to Puerto Rico and was reconstituted as an all-Puerto Rican formation. The island had its regiment back, but not for long. The 65th was de-activated in 1956. But the unit’s story did not end there.

A Rescue and Recovery Mission

Colonel César Cordero, who had led the 65th during the battle for Outpost Kelly, and who had advanced to brigadier general and adjutant general of Puerto Rico’s National Guard, led a campaign that culminated with the reactivation and transfer of the 65th from the regular army to the Puerto Rico National Guard in 1959. This is the first and only time in U.S. military history in which a federal unit, a unit of the regular United States Army is reconstituted as a National Guard outfit. Needless to say, this was a major concession to the Borinqueneers and the Puerto Ricans who insisted on saving their regiment, the Puerto Rican regiment.

This is the first and only time in U.S. military history in which a federal unit, a unit of the regular United States Army is reconstituted as a National Guard outfit. Needless to say, this was a major concession to the Borinqueneers and the Puerto Ricans who insisted on saving their regiment, the Puerto Rican regiment.

Unlike its participation during the war, however, this event received scant publicity and soon el sesenta y cinco and its epic ordeal during the Korean War faded into a distant and distorted memory. The Puerto Ricans had rescued their beloved regiment, but its history had not been restored. The Borinqueneers’ record remained stained.

The rescue, recovery and restoration process culminated with the awarding of the Congressional Gold Medal to the regiment. Since the American Revolution, Congress has commissioned Gold Medals as its highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions. Since George Washington received it, only 160 individuals and entities had been awarded the medal to date. Few combat units have earned this accolade. The 65th is the first unit to receive it for service during the Korean War and they join Roberto Clemente as the only Puerto Rican or Latino recipients.

Few combat units have earned this accolade. The 65th is the first unit to receive it for service during the Korean War and they join Roberto Clemente as the only Puerto Rican or Latino recipients.

Obtaining the award came from the efforts of many groups and organizations and, the Borinqueneers CGM Alliance (BCGMA). The effort to restore their record was led mostly from the diaspora, a diaspora the Borinqueneers helped to build.

The medal has been awarded to other famous minority units including the Tuskegee Airmen, the Navajo Code Talkers, the Nisei Soldiers, and the Montford Point Marines, and recently, the WWII Filipino Scouts. The Borinqueneers are the first unit from the Korean War to receive the award. The ethnicity and race of former recipients is no coincidence. All of them fought during times of crisis to defend a country that at the time treated them, at best, like second class citizens.

The medal recognizes the valor and sacrifice of units like the African-American marines and aviators whose bravery in combat, at a time when lynching was common and racial segregation the norm, disproved the myths of racial inferiority and unfitness for military service; the courage of Navajo code talkers, who at a time when their language was prohibited in schools, used it for communications in the battlefield saving countless American lives; or the pride of Japanese-American soldiers who volunteered to join the army and requested combat duty while their families were kept in internment camps.

The Borinqueneers made a similar contribution. The men of the 65th were willing to pay the ultimate price at a time when Puerto Ricans were openly labeled in the press, in academic circles, and by elected officials, “a problem” to be dealt with. The bill awarding the Congressional Gold Medal passed both houses of Congress unanimously. When President Barack Obama signed the bill On June 10, 2014, it recognized the honorable service of the 65th, which during the Korean War had to fight on two fronts. On both fronts the Borinqueneers conducted themselves with honor and dignity.

Dr. Frank Bonilla, the 65th, and the Center for Puerto Rican Studies are connected in many ways. Bonilla, a Puerto Rican born in New York, participated in the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 during WWII. In the spring of 1945 he was reassigned as replacement to the 65th Infantry. His experience with the Borinqueneers m changed his life. He noticed the men of the 65th coming to attention when La Borinqueña played. Even the food was different- and he enjoyed the rice and beans the regiment’s cooks always seem to find. In the middle of a war that took him all the way to France, Belgium and Germany, Frank felt at home in the 65th. After the war ended, he went back to Puerto Rico with the Borinqueneeers. It was his first time in Puerto Rico. There were parades to receive the soldiers and thousands of Puerto Ricans lined up the streets of San Juan with Puerto Rican and American flags to receive their Puerto Rican soldiers. He spent eight months in Puerto Rico with the 65th before going back to the United State and went back to New York changed by his experience with the Borinqueneers. He eventually founded the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, at Hunter College in 1973.

Even the food was different- and he enjoyed the rice and beans the regiment’s cooks always seem to find. In the middle of a war that took him all the way to France, Belgium and Germany, Frank felt at home in the 65th. After the war ended, he went back to Puerto Rico with the Borinqueneeers. It was his first time in Puerto Rico. There were parades to receive the soldiers and thousands of Puerto Ricans lined up the streets of San Juan with Puerto Rican and American flags to receive their Puerto Rican soldiers. He spent eight months in Puerto Rico with the 65th before going back to the United State and went back to New York changed by his experience with the Borinqueneers. He eventually founded the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, at Hunter College in 1973.

For over a decade now, we have witnessed the restoration and celebration of the Borinqueneers’ sacrifices during the Korean War. As it happened in the Puerto Rican archipelago during the war, avenues, plazas, and monuments have been named or built on their honor across the United States. And on April 13, 2021, we will observe for the first time, National Borinqueneers Day. For some, this may look like too little and too late- for most Borinqueneers have passed. Other critics will say it is too much- they did their duty, move on. It is not too much. The generation of Puerto Ricans who participated in this conflict, dubbed the Forgotten War, is quickly shrinking. Let us make sure that their sacrifices and their ordeal, and what they accomplished for Puerto Rico as they fought both the enemy and racism, is never forgotten. Let us not forget the meaning of the monuments, roads and plazas erected and named after them- or why Puerto Rico has so many Barrios and sectors named: Barrio or sector Corea.

And on April 13, 2021, we will observe for the first time, National Borinqueneers Day. For some, this may look like too little and too late- for most Borinqueneers have passed. Other critics will say it is too much- they did their duty, move on. It is not too much. The generation of Puerto Ricans who participated in this conflict, dubbed the Forgotten War, is quickly shrinking. Let us make sure that their sacrifices and their ordeal, and what they accomplished for Puerto Rico as they fought both the enemy and racism, is never forgotten. Let us not forget the meaning of the monuments, roads and plazas erected and named after them- or why Puerto Rico has so many Barrios and sectors named: Barrio or sector Corea.

And let us remember that they represented the hopes of a people willing to sacrifice their youth for a better future, to pay a tribute of blood in search for acceptance, respectability, equality, a path towards decolonization, and a democracy that has proven elusive to them.

In a ceremony before the unveiling of the Congressional Gold Medal, surviving Borinqueneers placed a wreath with the 65th’s crest in front of the Korean War Memorial in memory of the fallen Borinqueneers. Washington D.C. April 13, 2016. Image captured by author.

© Center for Puerto Rican Studies. Published in Centro Voices 12 April 2021.

1 El Imparcial de Puerto Rico: Periódico Ilustrado, 12 October 1950.

2 Periódico El Mundo (San Juan), 12 October 1950.

3 THE PROBLEM OF PUERTO RICAN MIGRATIONS TO THE UNITED STATES, HENRY L. HUNKER. Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, Columbus 10, THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE 51(6): 342, November, 1951. 342-346

The Film – The Borinqueneers

Borinqueneers Trailer

A DOCUMENTARY ON THE 65TH INFANTRY REGIMENT

About the Film

EL POZO PRODUCTIONS, in collaboration with Raquel Ortiz, acclaimed producer of Mi Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of The Borinqueneers, the first major documentary to chronicle the never-before-told story of the Puerto Rican 65th Infantry Regiment, the only all-Hispanic unit in the history of the U. S. Army. A one-hour version of this award-winning film premiered nationally on PBS in 2007 and on WTJX (the U.S. Virgin Islands’ PBS station) in 2011. A Spanish expanded version was broadcast on WIPR (Puerto Rico’s PBS station). The Armed Forces Network (AFN) broadcast the film for five years to more than 850,000 U.S. troops overseas. The Pentagon Channel also aired the film. Many screenings have been organized in various major cities throughout the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

S. Army. A one-hour version of this award-winning film premiered nationally on PBS in 2007 and on WTJX (the U.S. Virgin Islands’ PBS station) in 2011. A Spanish expanded version was broadcast on WIPR (Puerto Rico’s PBS station). The Armed Forces Network (AFN) broadcast the film for five years to more than 850,000 U.S. troops overseas. The Pentagon Channel also aired the film. Many screenings have been organized in various major cities throughout the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

Narrated by Hector Elizondo, the documentary explores the fascinating stories of courage, triumph and struggle of the men of the 65th through rare archival materials and compelling interviews with veterans, commanding officers, and historians.

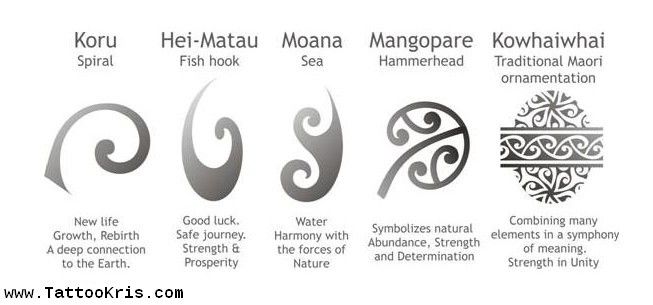

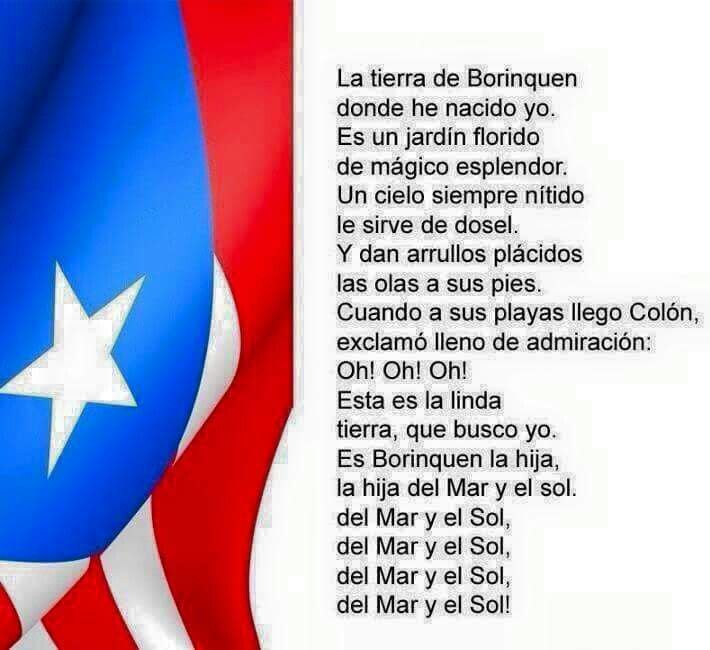

The 65th Infantry Regiment was created in 1899 by the U.S. Congress as a segregated unit composed primarily of Puerto Ricans with mostly continental officers. It went on to serve meritoriously in three wars: World War I, World War II and the Korean War. The unit was nicknamed after “Borinquen”, the word given to Puerto Rico by its original inhabitants, the Taino Indians, meaning “land of the brave lord”.

When they were finally called to the front lines in the Korean War, the men of the 65th performed impressively, earning praise from General MacArthur. They performed a critical role containing the Chinese advance and supporting the U.S. Marines in the aftermath of the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Sent to every corner of the peninsula, they showed outstanding resilience and a legendary fierceness as combatants, even as they faced discrimination within the Army. But in the fall of 1952 the regiment was at the center of a series of dramatic events that would threaten its very existence.

Puerto Ricans occupy a special place in the history of the U.S. Army. Because of the island’s commonwealth status, they don’t have the right to vote in U.S. elections, and yet they serve in the military and can be drafted. For many of the veterans of the 65th, this paradox became an incentive to be even more patriotic, to prove themselves in battle 200%.

Although thousands of Puerto Ricans have served courageously in the Armed Forces since World War I, their contribution and sacrifices have gone largely unnoticed. Until now. The Borinqueneers explores the rich history of this unique regiment and uncovers the circumstances that led to its darkest hour. This film is a result of extensive historical research and interviews with 250 veterans and commanding officers of the 65th Infantry from all over the United States and Puerto Rico. We have been honored by their support and willingness to share their stories with us.

Until now. The Borinqueneers explores the rich history of this unique regiment and uncovers the circumstances that led to its darkest hour. This film is a result of extensive historical research and interviews with 250 veterans and commanding officers of the 65th Infantry from all over the United States and Puerto Rico. We have been honored by their support and willingness to share their stories with us.

FILM FESTIVALS & SCREENINGS

- Award of Excellence – Accolade Competition, 2008

- Award of Excellence – Insight Awards by National Association of Film & Digital Media Artists (NAFDMA), 2008

- Award of Excellence for Hector Elizondo – Voice-over Narration – Insight Awards by NAFDMA, 2008

- Honorable Mention – Chris Awards, 2008

- Nominee for Best Documentary for Television – Imagen Awards, 2008

- Finalist – Outstanding Made-for-Television Documentary – ALMA Awards, 2008

- Finalist – Estela Award – National Association of Latino Independent Producers (NALIP), 2008

- Winner – Military Channel Award – GI Film Festival (Washington, DC), 2012

- Special Screening of 100 Years of Puerto Rican Cinema – Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano (Havana, Cuba), 2012

- Among the Best – 1st Ten Years – Latino & Native American Film Festival (CT), 2021 (Selected in 2016 as an “Official Selection”)

- Winner – Audience Award– Orlando Hispanic Film Festival (FL), 2009

- Best Professional Documentary – Real to Reel International Film Festival (NC), 2008

- Best Puerto Rican Documentary – Rincon International Film Festival (Puerto Rico), 2008

- Best Documentary – Georgia Latino Film Festival (GA), 2013

- Official Screening – Casa de America (Madrid, Spain), 2012

- Official Selection – Lancaster Latino Film Festival (PA), 2012

- Official Selection – Rochester Latino Film Festival (NY), 2012

- Official Selection – Buffalo International Film Festival (NY), 2012

- Official Selection – International Puerto Rican Heritage Film Festival (NY), 2012

- Official Selection – Cinesol Film Festival (TX), 2008

- Official Selection – Tulipanes Latino Art & Film Festival (MI), 2008

- Official Selection – Orlando Latin American Film & Heritage Festival (FL), 2008

- Official Selection – Puerto Rican Film Series, Puerto Rico Institute of Arts & Culture (IL), 2007

- Official Selection – Saginaw Film Festival (MI), 2009

- Official Screening – National Association of State Directors of Veterans Affairs Conference, 2012

- Official Screening – Organization of American Historians Annual Conference, 2009

- Official Screening – National Guard Equal Opportunity Annual Conference, 2008

REVIEWS

“A passionate rejoinder to Ken Burns, whose World War II documentary drew sharp criticism from Latino and American Indian groups for initially ignoring their contributions during that war…. The Borinqueneers gives a once-storied Puerto Rican regiment its due.” – The New York Times

The Borinqueneers gives a once-storied Puerto Rican regiment its due.” – The New York Times

“An excellent choice for libraries…. The strength of the film is the commentary provided by former members; they are exceptionally candid about their military experiences, reasons for serving, and relationships formed under fire. Historians’ and former military officers’ commentary provide an outside view of the regiment, praising their heroism and bravery. The film also examines how mismanagement of the unit by assigning non-Spanish-speaking officers led to mass insubordination and the arrest of 100 soldiers. A number of relevant topics are covered: racism in the military, America’s relationship with Puerto Rico, and the Korean conflict. But what makes the film most compelling is its examination of friendship and camaraderie under fire.” – School Library Journal

“Highly recommended for libraries serving Puerto Ricans or with collections of Puerto Rican studies… In a very effective interview technique, veterans of the 65th Infantry comment on its performance and express their pride in having served as American citizens despite the limits imposed upon them as a “colored” battalion. Issues pertaining to Puerto Rican culture are also presented, such as their strong adherence to religious customs, praying the rosary before fighting, and their playing music, even in the war camps.” – Criticas

Issues pertaining to Puerto Rican culture are also presented, such as their strong adherence to religious customs, praying the rosary before fighting, and their playing music, even in the war camps.” – Criticas

“The Borinqueneers, is both informative and heartbreaking. The film is a necessary step in revealing the complex history of these Puerto Rican soldiers — brave, proud men — and their contributions should be celebrated, especially given how they’re glaringly absent from history books… the film is dense and well-researched, and it does its best to remain objective, instead largely allowing viewers to interpret these historical events according to their own belief systems.” – Si TV

“Highly recommended… The film, sensitive to the plight of the 65th and its veterans, while remaining cautiously objective, should be considered required content for any collection or institution supporting a Puerto Rican population or Latin American studies.” – Educational Media Reviews Online

The Team

NOEMÍ FIGUEROA SOULET

Producer / Director / Writer

PATRICIA GARCÍA-RIOS

Consulting Producer

RAQUEL ORTIZ

Co-Producer / Director

HÉCTOR ELIZONDO

Narrator for English Version

MIGUEL PICKER

Editor and Original Music

DAVID ORTIZ ANGLERÓ

Narrator for Spanish Version

About the Team

Funding

Film Credits

Lyrics and lyrics Marc Anthony

I s what are the highlights

With my beautiful Borinquen

That’s why I want to like

By always calling the beautiful

I with them trigueas women

S smell your roses

4 my riquea land

By always calling beautiful

Caribbean island

Caribbean island

Borinquen

Call you Precious waves

The sea that bathes you

It is a great charm of

in EDN

and you have a noble Hidalgua

from the mother of Spain

and cruel bravo Indian song

We also have

Chorus:

Bards call you precious

Singing

History

No matter the tyrant heals

With black evil

Beautiful lasers without a flag

No laurel, no glory

Beautiful, beautiful

They call you sons of freedom

You are beautiful inside of me

Deep inside my heart di

And the more time goes by

T my love comes out

Because now I understand

Because now I understand

At least it happened

Being a puertoriqueo

Being a puertoriqueo

Wherever you go, Ooohhh

Cause it’s in my blood

About the inheritance of my fathers

And I repeat with pride

I love you Puerto Rico

I love you Puerto Rico

And that’s why I was born today

Dedicate this song

For this noble Jibarito Rafael

And my island of charm

Yaiko love you Puerto Rico

I love you Puerto Rico

I know that charming

About my beautiful Borinquen

That’s why I love her so much

And ill always call her precious

I know about my dark-skinned women

I know about the smell of her roses

That’s why to my rich country

Ill always call her precious

Caribbean

Caribbean

Borinquen

Calls you

ocean waves precious

you swim precious

ocean waves

Precious for being charming,

For being Eden

And you have nobility

Mother, Spain

And fiery song fierce Indian

You have it too

Chorus:

The bards sing This is your story

Call you precious

It doesn’t matter what the tyrant

Treats you with black hatred9

You will still be without

Precious flag, achieved or glory

Precious, precious

Youre Libertys call children

Precious, I carry you inside

Very deep in my heart

And the more time goes by

My love for you grows and grows

Because its now that I understand

Because its now that I understand

That no matter what happens

I will always be Puerto Rico

I will always be Puerto Rico

Because wherever I go, Oooohhhh

Because I carry it in my blood

Because of my parents’ heritage

And proudly repeat

I love you Puerto Rico

I love you Puerto Rico

And that’s why its born in me

To dedicate this song

This nobleman ** To Jibarito Rafael

And to my island with charms

I love you Puerto Rico 9003 love you Puerto Rico , Oooohhhh

Dancing with Dictators | Colta.

ru

ru

Dancing with Dictators | Colta.ru

March 24, 2014Contemporary music

11242

text: Egor Antoshchenko

1 of 6

close

Diplomatic sanctions and public condemnation do not always frighten representatives of show business: musicians and athletes are not averse to earning a million or two at the birthday or wedding of this or that dictator – they are not stopped even by unpleasant questions that they are then asked at home.

1. Jennifer Lopez

The ideals of democracy have never become an obstacle for J. Lo to earn extra money. Last year, Human Rights Watch accused the singer of earning $10 million speaking to dictators and corrupt businessmen.

Lopez sang at the celebration of the birthday of President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, where she performed not only her hits, but also a toast “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” . The singer’s management had to make excuses that she was not aware of human rights violations in Turkmenistan, but the president of HRW Thor Halvorssen was not satisfied with this excuse. “The fact that she does not know how to use Google could be believed if this was an isolated case,” said Halvorssen. In 2011, the singer performed at the birthday party of the son of Uzbek businessman Azam Aslamov, one of whose guests was Ramzan Kadyrov. Human Rights Watch urged the singer to return the fee for these performances, but it is not known whether this was done. Lopez was also invited to the anniversary of the general director of JSC “Slavyanka” Alexander Elkin – according to some reports, she was promised a fee of $ 2 million for the concert. A businessman suspected of embezzlement at the Ministry of Defense, who was friends with Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, was imprisoned the day before the celebration of the 50th anniversary.

Lopez sang at the celebration of the birthday of President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, where she performed not only her hits, but also a toast “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” . The singer’s management had to make excuses that she was not aware of human rights violations in Turkmenistan, but the president of HRW Thor Halvorssen was not satisfied with this excuse. “The fact that she does not know how to use Google could be believed if this was an isolated case,” said Halvorssen. In 2011, the singer performed at the birthday party of the son of Uzbek businessman Azam Aslamov, one of whose guests was Ramzan Kadyrov. Human Rights Watch urged the singer to return the fee for these performances, but it is not known whether this was done. Lopez was also invited to the anniversary of the general director of JSC “Slavyanka” Alexander Elkin – according to some reports, she was promised a fee of $ 2 million for the concert. A businessman suspected of embezzlement at the Ministry of Defense, who was friends with Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, was imprisoned the day before the celebration of the 50th anniversary.

Did you like the material? Help the site!

Share link / Share

twitter vkontakte

New in Contemporary Music sectionMost read

Today online

Colta Specials

“Social movement” in Russia of the XIX-XX centuries

Kirill Solovyov on the concept, scale and nature of the phenomenon

March 20, 202010750

Theater

Instead of war

Andrey Arkhangelsky about what remains – except for panic and fear

March 20, 202013540

Bridges

Claudia Pieralli.

Lopez sang at the celebration of the birthday of President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, where she performed not only her hits, but also a toast “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” . The singer’s management had to make excuses that she was not aware of human rights violations in Turkmenistan, but the president of HRW Thor Halvorssen was not satisfied with this excuse. “The fact that she does not know how to use Google could be believed if this was an isolated case,” said Halvorssen. In 2011, the singer performed at the birthday party of the son of Uzbek businessman Azam Aslamov, one of whose guests was Ramzan Kadyrov. Human Rights Watch urged the singer to return the fee for these performances, but it is not known whether this was done. Lopez was also invited to the anniversary of the general director of JSC “Slavyanka” Alexander Elkin – according to some reports, she was promised a fee of $ 2 million for the concert. A businessman suspected of embezzlement at the Ministry of Defense, who was friends with Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, was imprisoned the day before the celebration of the 50th anniversary.

Lopez sang at the celebration of the birthday of President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, where she performed not only her hits, but also a toast “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” . The singer’s management had to make excuses that she was not aware of human rights violations in Turkmenistan, but the president of HRW Thor Halvorssen was not satisfied with this excuse. “The fact that she does not know how to use Google could be believed if this was an isolated case,” said Halvorssen. In 2011, the singer performed at the birthday party of the son of Uzbek businessman Azam Aslamov, one of whose guests was Ramzan Kadyrov. Human Rights Watch urged the singer to return the fee for these performances, but it is not known whether this was done. Lopez was also invited to the anniversary of the general director of JSC “Slavyanka” Alexander Elkin – according to some reports, she was promised a fee of $ 2 million for the concert. A businessman suspected of embezzlement at the Ministry of Defense, who was friends with Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, was imprisoned the day before the celebration of the 50th anniversary.