Cuba indigenous groups: World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples

Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples

Environment

Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic.

The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands.

History

Pre-Colombian

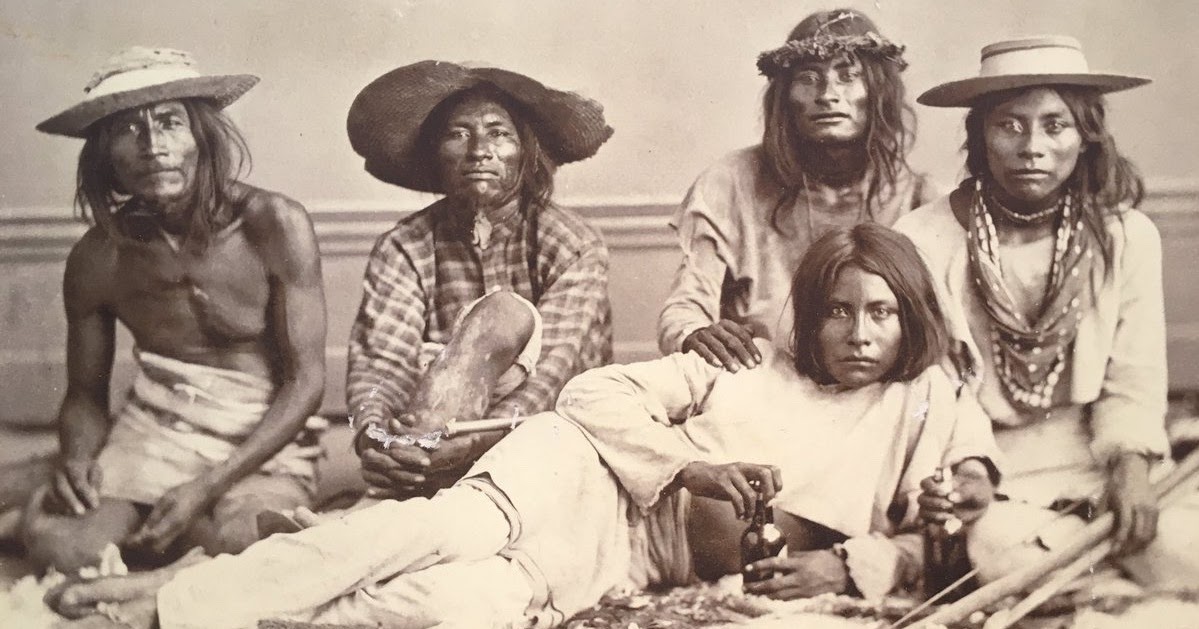

The original inhabitants of Cuba were the indigenous Ciboney and other Arawak speaking groups. As a result of the island’s location at the entrances to the Gulf of Mexico, as well as the Yucatán Channel, it was used by the early Taino Arawak (4000 BCE) in their original migrations from Belize and the Yucatán and across the windward passage to Hispaniola (Ay-iti). That neigbouring island subsequently became the regional centre of Taino-Arawak culture and religion and sent colonists back to eastern Cuba. The name Cuba, is derived from its original indigenous name, Cubanascnan.

That neigbouring island subsequently became the regional centre of Taino-Arawak culture and religion and sent colonists back to eastern Cuba. The name Cuba, is derived from its original indigenous name, Cubanascnan.

Early colonial

Columbus first landed on Cuba in 1492 but Spanish colonization of the island did not begin until 1511, with the establishment of settlements at Baracoa, Santiago de Cuba (1514) and Havana in 1515. Cuba served as a staging area for the successful Spanish colonizing expeditions to Mexico and Florida.

Although the first enslaved Africans were taken to Cuba in 1513, initial Spanish gold mining depended primarily on savage extortion of forced labour from the indigenous Taino-Arawak population. The Taino-Arawak mostly died in captivity, or engaged in resistance and disappeared into the remote mountains creating a labour shortage. This necessitated the importation of captured West Africans to provide the needed labour, with the first large group of enslaved Africans to work underground entering the mines in 1520.

The first recorded uprising of enslaved Africans in Cuba took place in 1533 at the Jobabo mines. Uprisings were frequent with the participants escaping into the mountains and linking with indigenous groups to forming maroon settlements called Palenques, from which they mounted raids on Spanish settlements. One of these maroon raids, conducted jointly with pirates in 1538, destroyed part of Havana.

Gold trade

Given its location on the Windward Passage that links the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, Cuba became a key part of the most important trade route in the New World. After the mid-1500s, gold, silver and emeralds from Spanish mining centres in Bolivia, Peru and Mexico were trans-shipped to Havana, Cuba, and then on to Spain.

As the capital of Cuba, Havana became a very important city. Havana held a monopoly on local as well as international trade, which reduced local interest in producing sugar in the surrounding countryside, and the need for forced labour on plantations. Enslaved Africans in Havana worked primarily at the ports, in construction (ships, housing), domestic service and also as artisans, merchants, small shopkeepers, and even as itinerant street vendors.

Enslaved Africans in Havana worked primarily at the ports, in construction (ships, housing), domestic service and also as artisans, merchants, small shopkeepers, and even as itinerant street vendors.

Cuba prospered as a trading hub and became the prime target of pirates, smugglers and rival European navies, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Despite trade regulations laid down by the Spanish crown colonists conducted brisk contraband trade with neighbouring colonies and privateers, thereby making it easy for the English to capture and occupy Havana in 1762-1763.

The British, who by then had a monopoly on slave trading, met the pent-up local demand for slave labour. During the year they controlled Havana, the British imported 10,000 Africans for sale in less than 10 months, mostly to work in the sugar factories (ingenios). After this the Spanish government liberalized its Cuban policy and encouraged greater agricultural development, commercial expansion. and increased colonization.

The remaining restrictions on trade were officially eliminated with the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, which encouraged Spaniards and later non-Spanish Europeans to settle and populate Cuba and Puerto Rico. Between 1774 and 1817 the population of Cuba increased from about 161,000 to more than 550,000, some of these being colonial refugees from the Haitian revolution.

The decree especially encouraged slave labour to revive agriculture and to attract the new settlers. Consequently large numbers of enslaved Africans continued arriving in Cuba after the late 1700s. This led to a significant rise in sugar production. Cuba became the worlds largest sugar producer, with a highly structured class and caste-conscious plantation society, in which cruelty towards dark-skinned Africans was routine practice.

This situation also led to increased African resistance to slavery and a high rate of escape to maroon Palenques. There were a series of slave uprisings in the island that would eventually become interwoven into the struggle for Cuban independence.

During the 1830s, in the effort to hang on to its few remaining colonies, Spanish rule became increasingly repressive. This provoked a widespread movement among the colonists for independence. Revolts and conspiracies against the Spanish regime, like those of 1834 and 1838, dominated Cuban political life throughout the remainder of the century.

By 1843 enslaved Africans constituted nearly half the Cuban population. With slavery already abolished elsewhere in the region, pro-slavery forces in both the United States and Cuba made periodic calls for the US to annex, buy or invade the island to help safeguard the profitable slave societies of both countries. Offers by the US government to purchase the island were repeatedly rejected by Spain.

In 1868 revolutionaries under the leadership of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, a wealthy landowner with pro-abolitionist sentiments, proclaimed Cuban independence. He raised an army composed mostly of freed slaves and fought against Spanish rule.

The ensuing Ten Years’ War became a costly struggle to both Spain and Cuba and also had an impact on its Caribbean neighbours. (See Dominican Republic) The guerrilla war raged mostly in the eastern provinces and took nearly 200,000 lives. It was terminated in 1878 by a truce granting many important concessions to the rebels, especially the abolition of slavery.

Slavery was finally abolished in Cuba in 1886, more than half a century after its elimination in the British Empire. Importation of cheap labour from China was ended by 1871 and the equal civil status of blacks and whites proclaimed in 1893.

US guidance

Despite the 1878 truce, the Spanish failed to institute the promised reforms, resulting in a resumption of revolutionary activities under the leadership of Jose Martí. The US seized the chance to intervene on the side of the rebels, precipitating the Spanish-American War. In April 1898, Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba, and the US established a military government in Cuba, setting up a new constitution in 1901.

As in all the previous battles, Afro-Cubans also played a prominent role in this War of Independence (1895-8), which finally ended Spanish colonial rule. However while the constitution of 1901 guaranteed formal equality for all Cubans, at the same time those in control pursued a policy of blanqueamiento (whitening) whereby 400,000 new Spanish immigrants were invited to enter Cuba between 1902 and 1919, making it the most Spanish of Latin American countries.

Furthermore Cubans still had not gained full and true independence. A few material benefits did accompany US occupation, but as in the nearby Dominican Republic it mainly allowed US corporate interests to gain control of the island’s resources, especially the sugar-industry which had long been connected to slavery, low wages and poor working conditions.

Popular dissatisfaction led to series insurrections that continued until the end of WW1. Mounting economic difficulties, caused by complete US domination of Cuban economy especially finance, agriculture, and industry, also marked the period following World War I. Unrest and frequent regime changes continued, but no real reforms occurred until Fulgencio Batista Zaldívar won the presidential contest of 1940 and served a term in office.

Unrest and frequent regime changes continued, but no real reforms occurred until Fulgencio Batista Zaldívar won the presidential contest of 1940 and served a term in office.

Revolution

Fluctuations in world sugar prices and a continuing inflationary spiral kept the political situation unstable in the postwar era.

In March 1952 the former president Batista seized power with army support, reintroduced reforms and in July 1953 crushed an uprising in Oriente Province led by a young lawyer named Fidel Castro, who went into exile.

Undaunted, Castro-led insurgents tried again in December 1956 and were once more defeated. Then in the tradition of the abolitionist Maroon Palenques, the group escaped to the mountains to plan and formed the 26th of July Movement. They used maroon-style hit and run guerrilla tactics to challenge the government, and mobilized considerable popular support. In March 1958, Castro called for a general revolt. On 1 January 1959, the revolutionary militia entered Havana, forcing Batista to resign and flee the country.

On 1 January 1959, the revolutionary militia entered Havana, forcing Batista to resign and flee the country.

Revolutionary Cuba

The reformist tendencies of the highly populist new Cuban regime alarmed US companies on the island. The agrarian reform laws and decrees prohibiting the operation of plantations controlled by non-Cubans mainly affected US sugar interests; So too did the initial revolutionary efforts to de-emphasize sugar production in favour of food crops.

The line was crossed when the Castro government expropriated an estimated US$1 billion in US-owned properties in 1960. The US imposed a trade embargo and broke off diplomatic relations. Furthermore, covert attempts to dislodge the Castro regime failed on April 17 1961, when the group of over 1,200 US-supported anti-Castro exiles who landed at the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba were either killed or captured.

US-Cuban relations grew still worse in the autumn of 1962, with the discovery of Soviet-supplied missile installations in Cuba, which caused a naval blockade.

In 1965 the Cuban government agreed to permit Cuban nationals to emigrate to the United States. Large numbers of European- descended Cubans took the opportunity. By April 1973, when the airlift formally ended, more than 260,000 mostly white Cubans had left, many to settle in South Florida.

In 1980, when Castro temporarily lifted exit restrictions again, another 125,000 people left for the United States. With the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s, Soviet-bloc aid and trade ended. As the effects of this change filtered down through the population, greater numbers of Cubans attempted to leave the country for economic reasons.

In February 1996, Cuban jet fighters shot down two civilian planes piloted by Miami-based exiles which the government said had violated Cuban airspace. Following this incident, US President Bill Clinton in March 1996 made permanent the economic embargo, which previously had been renewed each year. Canada, Mexico, and the European Union complained about the US law, arguing that it contravened World Trade Organization rules.

Peoples

Main languages: Spanish

Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions

The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population’s cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population.

More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule.

During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. During the 18th century this necessitated the steady importation of Africans in chains to provide forced labour, thereby creating an enduring set of colour, caste and class relationships and contributing to the present profile of the national population.

Chinese

Besides the large number of Cubans of African descent, there is a small but visible Chinese minority. Chinese began migrating to Cuba in 1847 as indentured labourers to work on the sugar plantations. Over several decades hundreds of thousands arrived to replace and/or work alongside enslaved Africans. At the end of their contracts some Chinese immigrants settled permanently in Cuba. In addition, in the late 1800s some 5,000 Chinese immigrated from the US to avoid the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

Generations of Chinese-Cubans married into the larger Spanish, mulatto and Afro-Cuban populations. Today almost all Chinese-Cubans have African, Spanish, and Chinese ancestry. Many have Spanish surnames. The majority of Chinese left after the revolution. However, as part of a cultural rescue and tourism promotion, Cuban Chinese have been provided with small businesses, like beauty parlours, mechanical shops, restaurants, and small groceries to help them recreate a scenic Barrio Chino (Chinatown).

Today almost all Chinese-Cubans have African, Spanish, and Chinese ancestry. Many have Spanish surnames. The majority of Chinese left after the revolution. However, as part of a cultural rescue and tourism promotion, Cuban Chinese have been provided with small businesses, like beauty parlours, mechanical shops, restaurants, and small groceries to help them recreate a scenic Barrio Chino (Chinatown).

Governance

Cuba is governed under a 1976 constitution that defines the country as a socialist state. All power belongs to the working people and the Communist Party is the country’s sole political party.

The central legislature of Cuba is the National Assembly of People’s Power, whose 510 members are elected to five-year terms by universal voting. The Council of State includes a president, who is the country’s head of state.

Judicial power is exercised by the People’s Supreme Court and courts of justice at provincial or regional levels. When required, revolutionary tribunals are convened to deal with crimes against the state.

When required, revolutionary tribunals are convened to deal with crimes against the state.

Sugar and sugar products make up about 75 per cent of annual Cuban exports. Tobacco, nickel and copper ores, foodstuffs, and petroleum products are other important export commodities. A second crop of commercial importance is tobacco, a large part of which is manufactured into the internationally popular Havana cigars.

The collapse of Eastern bloc communism in 1989 signalled the end of Cuba’s preferential trading relationship with the Soviet Union and led to a severe economic crisis. As one of the last centrally planned economies in the world, Cuba began to introduce market reforms while attempting to preserve its existing political system.

Minorities

- Afro-Cubans

Resources

Minority based and advocacy organisations

Centro Félix Varela

Tel: +53 776 337 731

Email: [email protected]

Centro De Estudios De America

Tel: +537 206 745

Sources and further reading

General

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2005, retrieved 14 May 2007, http://www. state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61723.htm

state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61723.htm

Afro-Cubans

Breaking the Silence: Learning about the Transatlantic Slaved Trade. Slave Routes: Cuba. retrieved 14 May 2007, http://www.antislavery.org/breakingthesilence/slave_routes/ slave_routes_cuba.shtml

Dzidzienyo, A. and Casal, L., The Position of Blacks in Brazilian and Cuban Society, London, MRG report, 1971, 1979.

McGarrity, G. and Cárdenas, O., ‘Cuba’, in MRG (ed.), No Longer Invisible: Afro-Latin Americans Today, London, Minority Rights Publications, 1995.

Stubbs, J. and Perez Sarduy, P. (eds), Afro-Cuba: An Anthology of Cuban Writing on Race, Politics and Culture, London, Latin America Bureau, 1993.

Copyright notice: © Minority Rights Group International. All rights reserved.

Indigenous Cuba: Hidden in Plain Sight

Cuba is picturesque everywhere, but most visitors trek to the more accessible western end of the island – Havana and the nearby white-sand beaches, the historic bay and its boardwalk (malecón). This is the tourist mecca of colonial architecture and burgeoning arts, old time cars in a modern metropolis.

This is the tourist mecca of colonial architecture and burgeoning arts, old time cars in a modern metropolis.

But Cuba the island – in the popular imagination and poetry – is a long crocodile (caiman). The west – and Havana – is the tail. The head of the caiman, my old people always said, is in the rugged east, the craggy mountain cordilleras of the fabled region called Oriente.

“Tierra soberana,” sing the troubadours – “sovereign land.”

Cuba begins through the Oriente, where the most settled Indian territories or cacicazgos, held sway. Through here the Spanish arrived in their conquest of Cuba in 1511 and here it was that the early Indian rebellions later evolved into the independence movements and wars of the 19th century. José Martí, the “Cuban Apostle” in the war against Spain was killed in battle near here. Teddy Roosevelt fought Spanish infantry nearby, at San Juan Hill. Even Fidel Castro’s revolution of the 1950s emerged in the history of these eastern mountains.

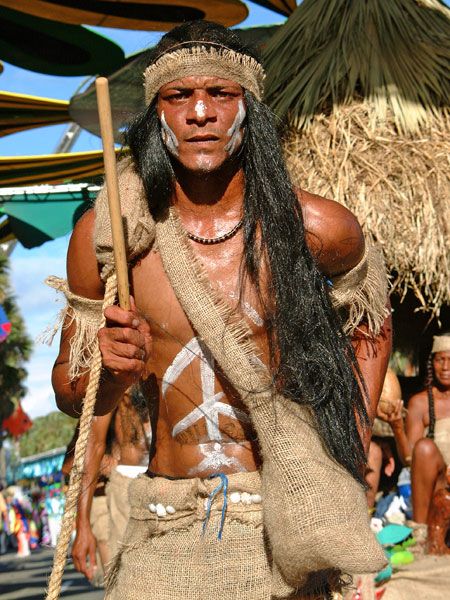

“Cuba profunda,” Alejandro Hartmann, calls it, “Deep Cuba.” Hartmann is city historian and director of the Matachin Museum, in the town of Baracoa, an ancient Native (Taíno) coastal village that became the first Spanish settlement in Cuba. Baracoa is still considered the gateway to indigenous Cuba. When Hartmann refers to Cuba profunda, he is signaling this reality: despite all the claims of Native people’s extinction in the Caribbean, in this region, encompassing the thick mountain chains inland from Baracoa to Guantanamo, and through the wider sierras, a Cuban indigenous presence is still recognizable.

I recently trekked with Hartmann up the coastal hills to the mountain cordilleras and the Indian community of La Rancheria. We went to visit our old friend, cacique Francisco Ramirez Rojas, “Panchito.”

La Rancheria is one of numerous small caserios or homesteads of the Native descended clan of Cubans known as the Rojas-Ramírez, called by anthropologists “la Gran Familia,” or the largest family in Cuba. The Rojas-Ramírez families are descendants of the Native Caribbean people that today are popularly and academically known as the Taíno. There are numerous caserios of Rojas-Ramírez families in over 20 localities in the Cuban eastern mountains and coasts, a kinship with upwards of 4,000 people.

The Rojas-Ramírez families are descendants of the Native Caribbean people that today are popularly and academically known as the Taíno. There are numerous caserios of Rojas-Ramírez families in over 20 localities in the Cuban eastern mountains and coasts, a kinship with upwards of 4,000 people.

The particular community of La Rancheria is nestled high up the wooded mountains of a pueblo called Caridad de los Indios. Nearby, about half an hour by horse, is another Native community of La Escondida, or “the hideout.” These were the most remote refuge areas – called palenques, in Cuba – where numerous Indian families migrated after losing lowland farms and their last Indian jurisdiction, El Caney, as late as 1850.

After four hours of riding up the mountain first in a jeep, then a large open truck, we find Cacique Panchito in good health. At 81, he has taken up using a cane, but has good mobility and is lucid as ever. Healthy and mobile too is the family matriarch and Panchito’s wife of 60 years, Reina. They are busy today with a visit from several related families. A pig has been butchered by sons and grandsons, who are making fire and roasting it in a pit. Several of their daughters and granddaughters chat and cut up tubers such as malanga, boniato and yucca – all original Indian crops – and sort rice, corn and beans to cook for the feast.

They are busy today with a visit from several related families. A pig has been butchered by sons and grandsons, who are making fire and roasting it in a pit. Several of their daughters and granddaughters chat and cut up tubers such as malanga, boniato and yucca – all original Indian crops – and sort rice, corn and beans to cook for the feast.

Panchito Ramirez is a born and bred Indio campesino, whose deep roots in the teachings of his elders singled him out for respect and recognition as main authority – cacique – of his community for more than 40 years. Other caciques had come before him in these remote mountain communities, but were so marginalized and out of sight that the national society assumed all Cuban Indians extinct. The reality of actual small communities was obscured by the fog of national scholars who predicated a strict Spanish-African origin for the Cuban population, repeatedly denying the indigenous strand in the national braid.

Panchito has pressed the fact of his community’s existence for over 30 years, a consistent effort to break through the wall of invisibility built by the adamant and widespread assertion of extinction for Cuban Native peoples. Among other regional historians, Hartmann refers to the fact of many Indian families surviving through colonial times as “something well-known in the eastern region.” He added: “This idea of a total Indian extinction was prescribed and cemented by cosmopolitan scholars.” The researchers who established the extinction dictum, he said, wrote from limited archival research and kept repeating each other. “Few visited and none of them studied in these mountains.”

Panchito touched on the subject during our visit, recounting the long and compelling history of his particular kinship gens, the Rojas-Ramírez families. The ancestry goes back to the last wave of indigenous settlement in Cuba – Taíno – who greeted the Spanish conquest and who, contrary to the popular narrative of their extinction, actually survived, as small groups and through intermarriage, through the centuries. It happened in Cuba that the Spanish colonial encomienda, based on the imposed labor of Indians, gave way to the founding of several pueblos of free Indian families. Among these, San Luis de los Caneyes (El Caney), near Santiago de Cuba, became the origin and survival place for the Rojas-Ramírez families for three centuries. These newly liberated or recently isolated Indian families were granted the names Rojas and Ramirez, en masse, in baptisms under a Spanish governor and a Bishop with those last names.

It happened in Cuba that the Spanish colonial encomienda, based on the imposed labor of Indians, gave way to the founding of several pueblos of free Indian families. Among these, San Luis de los Caneyes (El Caney), near Santiago de Cuba, became the origin and survival place for the Rojas-Ramírez families for three centuries. These newly liberated or recently isolated Indian families were granted the names Rojas and Ramirez, en masse, in baptisms under a Spanish governor and a Bishop with those last names.

The Spanish Royal grant of Indian jurisdiction over their community lands in El Caney was squelched by the colonial audiencia in 1850, but several Indian kinship or extended family groups remained together as they resettled in more remote lands over the mountains. “In my childhood here,” Reina explains, “la Rancheria was all Indian families; just in this community we had 30 houses or more. Now we are only 12 houses here. Many moved to the coast and other places looking for better conditions. ”

”

As of 2016, dozens of Rojas-Ramírez multifamily homesteads are scattered throughout the eastern mountains and a formal family count of the kinship group, still incomplete, stands at around 4,000. The Indian families as a whole retain considerable traditional ecological knowledge, along with legendary stories and ceremonies of fertility and protection that invoke the Moon, the Sun and the Mother Earth. In their healing traditions, they work with sacred trees, and they make wide use of medicinal herbal plants. They are proud agriculturalists – campesinos – who enjoy and suffer the ups and downs of raising crops on the land.

Along with Hartmann and a research team of community members, we traveled these thin mountain trails and visited with a good range of the Rojas-Ramírez folks. Beyond the bustle of the city and the frenetic salsa-driven cubanía of urban culture, a core of the national soul, the essence of its origin, resides in the Cuban countryside, in the mountains and remote coastal areas, among the people who work the land with the old Indian coa, or digging stick, plow with oxen-driven rigs and still ride horses as their main source of transportation. The high mountain lifestyle incorporates many Spanish and African cultural elements, yet the sense of Native belonging is obvious. This Cuba profunda, as Hartmann deems it, still yields a wonderful oral tradition, of the people and by the people.

The high mountain lifestyle incorporates many Spanish and African cultural elements, yet the sense of Native belonging is obvious. This Cuba profunda, as Hartmann deems it, still yields a wonderful oral tradition, of the people and by the people.

After half a century of socialist revolution, a new Cuban generation seeks to deepen its identity, to see and experience an everwidening vision of society. In Cuba, as in most of the Americas, exploring the deeper layers of a country’s cultural origins reveals foundational forces, within which resonates indigeneity, the nexus of the people and the land.

It surprises many people, even many Cuban people, that an indigenous community of substantial documented history and contemporary presence exists. It particularly elates many people that the elders of the Indian families continue to express spiritual and practical messages of respect for the Mother Earth and the productive qualities of mountain-farming techniques.

For a country that experienced severe food shortages, and near-starvation conditions just a generation ago, it is a message that resonates. Many well remember that when the high-input Soviet style farms went defunct with the whole socialist bloc, it was in fact the old Taíno crops and endemic herbal medicines, applied along with new organic farming technologies, that saved the country from starvation.

Many well remember that when the high-input Soviet style farms went defunct with the whole socialist bloc, it was in fact the old Taíno crops and endemic herbal medicines, applied along with new organic farming technologies, that saved the country from starvation.

In Cuba, the discussion goes beyond acknowledging the Indian kinship group of the Rojas-Ramírez people of the Oriente. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, a broader debate on Cuban identity issues has intensified as well. Things ancient and traditional, practical and high-minded constitute a current of discussion. A vigorous urban agriculture, a green or agro-ecological movement grew and has matured in the past 30 years.

As elsewhere, the discussion of indigeneity is impacted by new genetic studies, which for Cuba reveal that 34.5 percent of the general population is inheritor of Native-American mitochondrial DNA. The highest levels are found in the eastern region of Cuba: Holguín (59 percent) and Las Tunas (58 percent). This news has dealt a frontal blow to the historical dictum of early Native extinction.

This news has dealt a frontal blow to the historical dictum of early Native extinction.

A current of scholars and, more interestingly, of young activists is finally excavating not only archeological material but intangible cultural elements of indigenidad en la cubanía. A new direction is suggested; writes new generation Cuban scholar Robaina Jaramillo: “[Academic thinking] limited… our self-concept in the Cuban cultural identity… by omitting…the first transculturation process in the genesis of the Cuban nation, [that] between Indian and Spanish and Indian and African.”

After years of modest traveling through Cuba rekindling the Native family bonds, the old campesino Cacique Panchito, mostly non-literate, formally broke through the historical extinction barrier in 2014, when his community was acknowledged at a formal national-international conference on Indigenous cultures of the Americas. He got to bring his message there, and to introduce his daughter, Idalis, to help him represent their community.

As always, Panchito’s message was about working, loving and dreaming Mother Earth. Very simply, very consistently, he frames his words around the most important issue: invoking the proper farming and forestry techniques, and the spiritual values that underpin such a philosophy, to produce food and other natural gifts for the people. His consistent representation of the spiritual values that can still inform Cuba’s strong movement of ecoagriculture has resonated with currents in the new generation ready to engage the issues of people and the land.

Today, one of Panchito and Reina’s daughters has requested a community baptism for her newborn granddaughter. The job belongs to Doña Luisa, 94, oldest woman in the community. A circle is formed, outside, and under the midday sun. Doña Luisa bundles herbs with which to bless with water and leads a long prayer. The baptism has Christian elements but it is not merely so. A signal song and prayer of the community, appreciation to the Sun and the Moon, is intoned.

The grandmother requests a tobacco prayer circle. She asks Panchito and Idalis to lead it. The rolled cigar is lit and smoked to the four directions. Panchito calls on his prayer to the natural potencies of the world. As he ends, the elder woman of the community sanctifies the baby and presents her to her parents, she reminds them, “now no longer just of the monte, and as casi, or almost-Christian.”

I asked Panchito later why the term almost-Christian? “Because we respect everything,” he says. “The nina belongs to her parents, and she belongs to us, she belongs to the nation, she belongs to nature, and she belongs to God.”

Doña Luisa says. “Yes, we have our own way of being (“nuestra manera de ser”).”

News detail RU – DOCIP

- you tube

Stay up to date with news affecting indigenous peoples every day: conferences, documentation, international processes, debates, etc.

Being a Docip volunteer is about using your knowledge and skills to help Indigenous peoples during their participation in UN activities.

Tweets by @Docip_en

Docip @Docip_en 01-11-22 – 13:24

New call for applications from the UN Voluntary Fund for Indigenous Peoples👉 https://t.co/ESAOM1kybc#TreatyBodies… https://t.co/Npxt9cvWKu

Stay up to date with news that affects Indigenous Peoples. Subscribe to our newsletter!

14.01.2022

16 – January 22, 2022

89th meeting of the Children’s Rights Committee

January 17 – February 11, 2022, Palace of Nations, Switzerland

- 9000 9000 9000 9000

- Provisional agenda (English)

- Consideration of State reports: Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Djibouti, Greece, Kiribati, Madagascar, Netherlands, Somalia

003 Website

Fourth intersessional meeting of the Human Rights Council on Human Rights and the 2030 Agenda

January 18, 2022 Virtual Session

- Topic: on human rights”

- Web site

- Preliminary agenda (English)

- Conceptual Note (English)

Outgoing Fores

Acceptance: Photo of WHIS for Youth from among the indigenous peoples and local communities

9000

Call for Applications – Membership in the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 2023-2025

- Deadline: January 25, 2022

Novelty: Request for comments: draft general recommendations on the rights of women and girls from among the indigenous peoples (KLJ)

- Outopoi: January 31, 2022

Novinka: Supply: Call United Nations Report on Violence against Indigenous Women and Girls (Special Rapporteur)

- Deadline: January 31, 2022

Call for Applications: EMRIP Study on Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements Among Indigenous Peoples and states, including the peace agreement and reconciliation initiatives and their constitutional recognition”

- Out of term: January 31, 2022.

Acceptance of applications: EMPKN report on “Militarization of land of indigenous peoples: an approach based on human rights”

- Otherwise: January 31, 2022

Request for participation in the Study of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

- Deadline: February 2, 2022

Call for Applications: Report on Mercenary Victims, Mercenary-Associated Entities and Private Military and Security Companies

- Out of time: February 28, 2022.

Novelty: NGO contributions to the reports of interested parties for mentioned 41 (October – November 2022)

countries: Bahrain, Ecuador, Tunisia, Morocco , Indonesia, Finland, Great Britain, India, Brazil, Philippines, Algeria, Poland, the Netherlands, South Africa

- Otherwise: March 31, 2022

Future

40th session of the universal periodical.

)

)

January 24 – February 4, 2022, Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland

- Website

- Registration and information

- Planned countries: Sudan, South Iceland, Lithuania , Sudan, Syria, Timor-Leste, Togo, Uganda, Venezuela and Zimbabwe

49th Human Rights Council

28 February – 1 April 2022, Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland

- Website

- Registration

21st session of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples

April 25-May 6, 2022, UN headquarters, New York, USA

- Web sites

Military publications recent publications

- IACHR: The Right to Self-Determination of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (English | Spanish)

- Looking Back and Looking Forward: Orang Asli Self-Government and Democracy (English)

The latest additives to our online documentation center:

- 10th UN Business and Human Rights Forum

- KS26 RKICOON

Send us your proposals or corrections related to the Calendar of Meetings news!

<- back to: News

Refworld | Search by publisher

Last update:

Friday, October 28, 2022 at 14:45 GMT

- English

- | Español

- | Russian

- UNHCR

- Legislation

- Jurisprudence

- Country information

- View

- Resources

- My Profile

- Home page»

- Search by publisher»

- Narrow your search

- Type

- Country

- Subject

- Type

Search using this filter did not return any results.