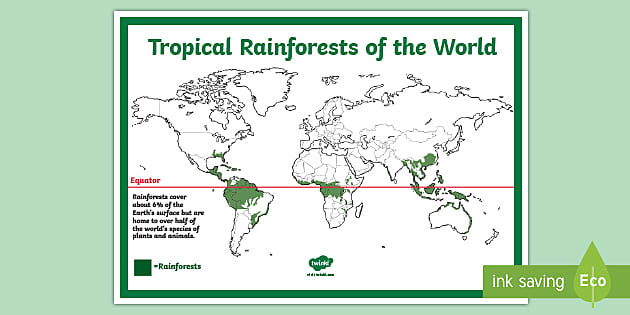

El yunque rainforest map: Map of the El Yunque rainforest trails on road #191

Hiking El Yunque Caribbean National Forest in Puerto Rico

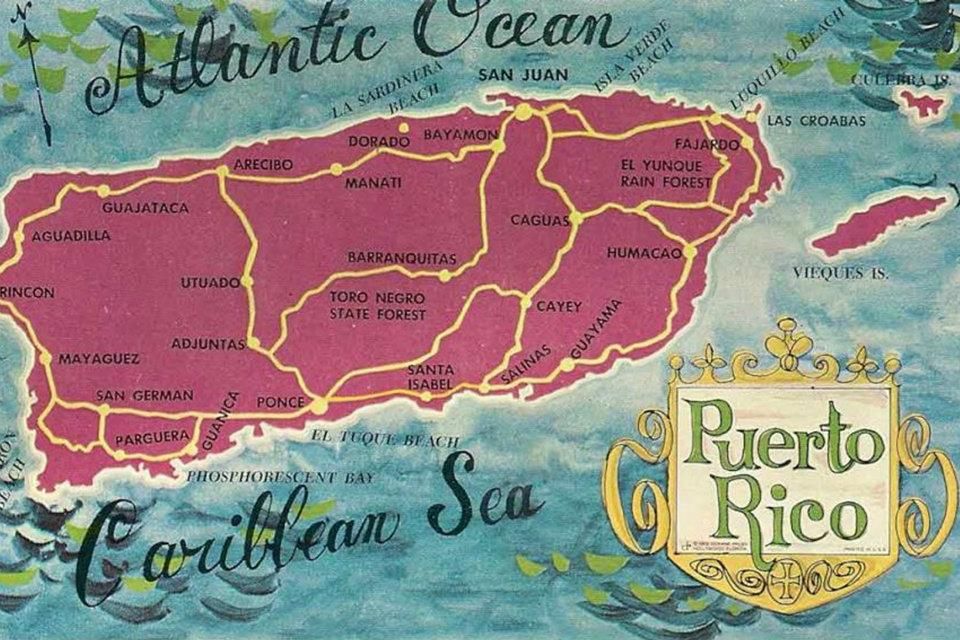

It is commonly called El Yunque rainforest, but the official name of this spectacular natural preserve is the Caribbean National Forest. The name El Yunque technically refers to the forest’s second-highest peak (3,469 ft.), and it’s also the name of the forest’s recreational area. But regardless of its moniker, it is without a doubt Puerto Rico’s crowning jewel of natural treasures.

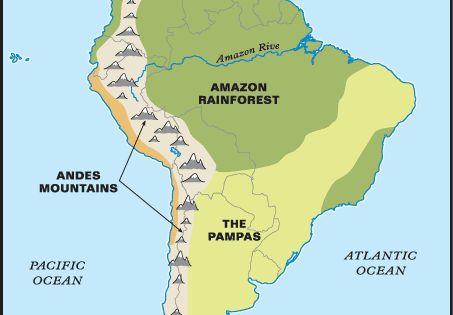

The only tropical forest in the U.S. National Forest System—not to mention the smallest and most ecologically diverse—the Caribbean National Forest is a must-see for visitors to Puerto Rico. Nearly half of the 28,000-acre area contains some of the only virgin forest remaining on the island, which was completely covered in forest when Columbus arrived in 1493. It also contains one of the world’s most accessible rainforests.

El Yunque National Forest, Puerto Rico. Photo © Geoff Gallice CC-BY via Wikimedia Commons.

El Yunque is about 35 minutes east of San Juan off Carretera 3. Go south on Carretera 191 and it will take you into the forest and to El Portal Tropical Forest Center.

Go south on Carretera 191 and it will take you into the forest and to El Portal Tropical Forest Center.

Trails

Although it’s possible to do a quick drive-by tour of El Yunque, the only way to fully appreciate its beauty and majesty is to park the car and hike into the jungle. It doesn’t take more than a couple of dozen steps to become completely enveloped by the dense lush foliage. One of the greatest joys of hiking in El Yunque is the sound. Here the aural assault of the 21st century is replaced by a palpable hush and the comforting, sensual, eternal sounds of water dripping, gurgling, rushing, raining. It’s more restorative than a dozen trips to the spa.

El Yunque Caribbean National Forest

There are 12 trails spanning about 14 miles in El Yunque. Many of the trails are paved or covered in gravel because the constant rain and erosive soil would require continuous maintenance to keep them passable. Nonetheless, hiking boots with good tread are a necessity. Even paved trails can be slippery and muddy. The warm air and high humidity also require frequent hydration, so bring plenty of water. And naturally, it rains a lot, so light rain gear is recommended. Avoid streams during heavy rains as flash floods can occur. Primitive camping is permitted in some areas. Permits are required and can be obtained at El Portal Tropical Forest Center.

The warm air and high humidity also require frequent hydration, so bring plenty of water. And naturally, it rains a lot, so light rain gear is recommended. Avoid streams during heavy rains as flash floods can occur. Primitive camping is permitted in some areas. Permits are required and can be obtained at El Portal Tropical Forest Center.

Footpaths at El Yunque National Forest. Photo © drbeachvacation, via Wikimedia Commons.

The following trails are found in El Yunque Recreation Area. All trail lengths and hiking times are approximate.

- Angelito Trail (0.5 mile, 15 minutes, easy, clay and gravel) crosses a stream and leads to Las Damas, a natural pool in the Mameyes River. To get to the trailhead, proceed south on Carretera 191 just past El Portal and turn left on Carretera 988, 0.25 mile past Puente Roto Bridge.

- La Coca Trail (2 miles, 1 hour, moderate to strenuous, gravel) starts at La Coca Falls and requires navigating over rocks to cross a couple of streams.

- La Mina Trail (0.5 mile, 25 minutes, moderate, paved and steps) starts at Palo Colorado and follows the La Mina River, ending at La Mina waterfall, where it connects with Big Tree Trail.

- Big Tree Trail (1 mile, 35 minutes, moderate, paved and steps) is an interpretive trail with signs in Spanish and English. It passes through tabonuco forest, over streams, and ends at La Mina waterfall, where it connects to La Mina Trail. The trailhead is by a small parking area at Carretera 191, kilometer 10.2.

- Caimitillo Trail (0.5 mile, 25 minutes, easy, paved and steps) begins at Sierra Palm Recreation Area and crosses a stream. Along the way you’ll pass a picnic area and structures used by the Puerto Rican parrot recovery program. It connects to the Palo Colorado Visitors Center and El Yunque Trail.

- Baño de Oro Trail (0.25 mile, 20 minutes, moderate, paved and gravel) starts just south of the Palo Colorado Visitors Center and passes by Baño de Oro before connecting with El Yunque Trail.

- El Yunque Trail (2.5 miles, 1 hour, strenuous, paved and gravel) is one of the forest’s longest and most strenuous hikes. It starts a little north of the Palo Colorado Visitors Center and climbs to an altitude of 3,400 feet. Along the way it passes several rain shelters, through the cloud forest, and ends at the peak of El Yunque. The lower part of the trail is accessible from Caimitillo Trail and Baño de Oro Trail. The higher reaches of the trail connect with Mount Britton Trail and Los Picachos Tower Trail.

- Mount Britton Trail (1 mile, 45 minutes, strenuous, paved) starts at Carretera 9938, a loop road at the end of Carretera 191. It is an uphill hike through tabonuco, sierra palm, and cloud forests. The trail crosses two streams and runs along a service road for a short distance—if you’re not sure which way to go, just keep heading straight up. It ends at the Mount Britton Tower, built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

- Mount Britton Spur (1 mile, 30 minutes, moderate, paved) connects Mount Britton Trail to El Yunque Trail.

- Los Picachos Trail (0.25 mile, 25 minutes, strenuous, unpaved and steps) is a steep ascent from El Yunque Trail to an observation deck built by the CCC.

The forest’s remaining two trails are outside El Yunque Recreation Center on the western side of the forest. The trails are unpaved, muddy, not maintained, and often overgrown in parts. Long sleeves and pants are recommended for protection against brush, some of which can cause skin irritation on contact. These trails are for adventurous hikers who really want to get away from it all.

- Trade Winds Trail (4 miles, 4 hours, strenuous, primitive) is the forest’s longest trail. To reach the trailhead, drive all the way through El Yunque Recreation Area to the end of Carretera 191 where the road is closed. Be mindful not to block the gate. Walk past the gate 0.

25 mile to the trailhead. The trail ascends to the peak of El Toro, the highest peak in the forest, where it connects with the El Toro Trail.

25 mile to the trailhead. The trail ascends to the peak of El Toro, the highest peak in the forest, where it connects with the El Toro Trail. - El Toro Trail (2 miles, 3 hours, difficult, primitive) starts at Carretera 186, kilometer 10.6, and traverses tabonuco, sierra palm, and cloud forests. It connects with the Trade Winds Trail.

Related Travel Guide

El Yunque National Forest Map – Map-N-Hike

Item added to cart!

790 :: El Yunque National Forest Map

$7.95

$14.95

-47% OFF

$7.95

$14.95

-47% OFF

0

LEFT IN STOCK

Tags:

Puerto Rico & Virgin IslandsTrails Illustrated Topographic Map

• Waterproof • Tear-Resistant • Topographic Map

Let National Geographic’s Trails Illustrated map of El Yunque National Forest guide you as you explore this tropical rain forest on the eastern side of Puerto Rico. Created in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service and others, this expertly researched bilingual map (English and Spanish) is a comprehensive guide to the area for all outdoor enthusiasts, novice and experienced alike. Not only is there an abundance of recreation information, but also background information about the forest, its history, plant and animal life, climate, points of interest, safety tips and accommodations. A trail guide will help you select a suitable area to explore, with trail descriptions, length and hiking time.

Created in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service and others, this expertly researched bilingual map (English and Spanish) is a comprehensive guide to the area for all outdoor enthusiasts, novice and experienced alike. Not only is there an abundance of recreation information, but also background information about the forest, its history, plant and animal life, climate, points of interest, safety tips and accommodations. A trail guide will help you select a suitable area to explore, with trail descriptions, length and hiking time.

The map covers the entire forest, including the Baño de Oro Natural Area, enhanced by an inset map showing the El Yunque Recreation Area in greater detail. Clearly pinpointed trailheads and mapped trails will lead you on your adventure. Other marked facilities and recreation features include picnic areas, drinking water stations, restrooms, parking areas. scenic overlooks and lookout towers. Your navigation will be aided by the map’s contour lines, elevations, water features, selected waypoints and clear boundaries between public and private land, as well as a complete road network of the area.

Every Trails Illustrated map is printed on “Backcountry Tough” waterproof, tear-resistant paper. A full UTM grid is printed on the map to aid with GPS navigation.

Other features found on this map include: El Toro Wilderness, El Yunque National Forest, Sierra de Luquillo.

Folded Size: 4.25″ x 9.25″

Flat Size: 37.75″ x 25.5″

Scale: 1:25,000

Copyright Date: 2001

Weight: 3 oz

Page Count: 2

Zoom

Map

The Perfect Companion

Never trust your life to a battery! Learn how to navigate with map and compass.

+

-29% sale

+

-47% sale

Total price: $57. 90$84.95

90$84.95

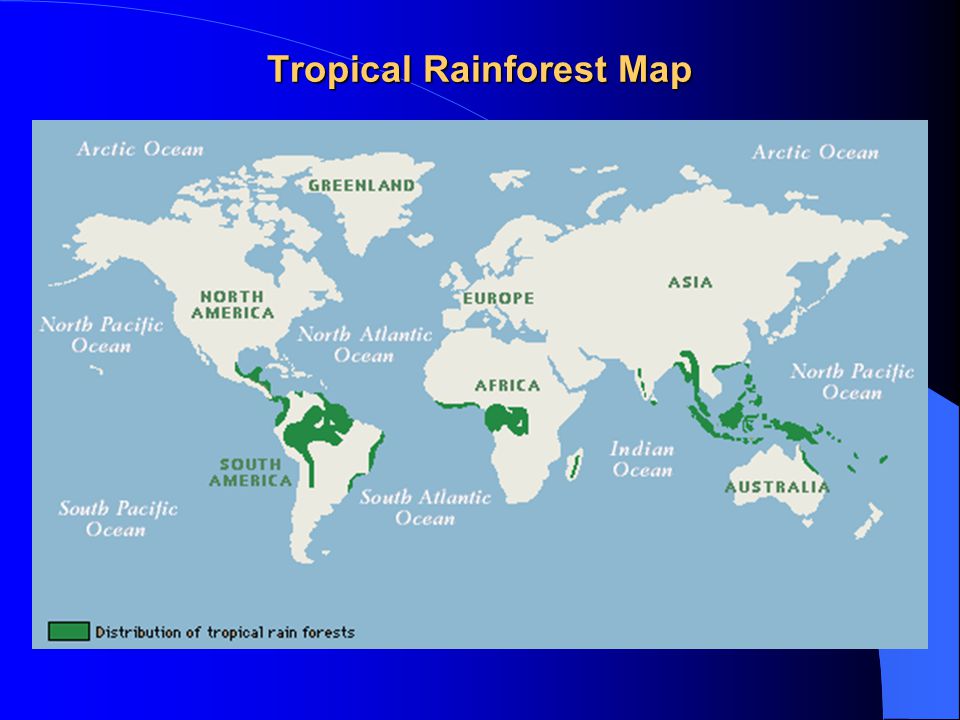

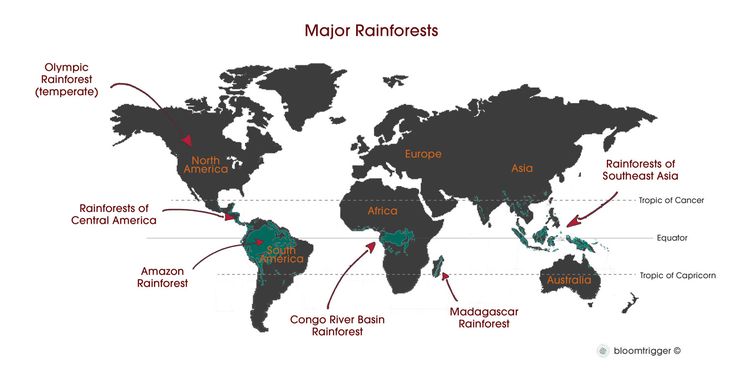

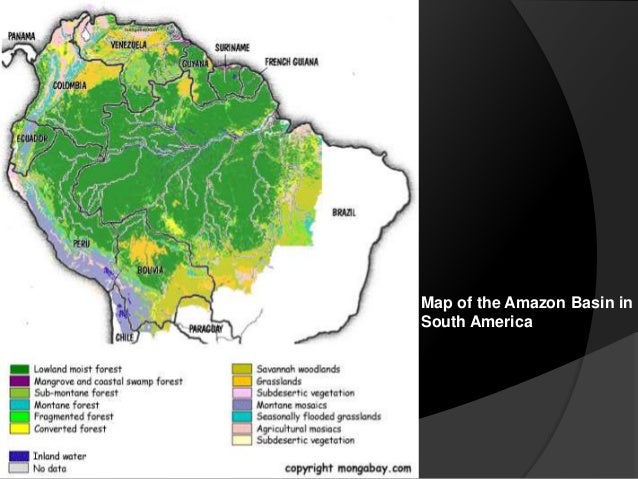

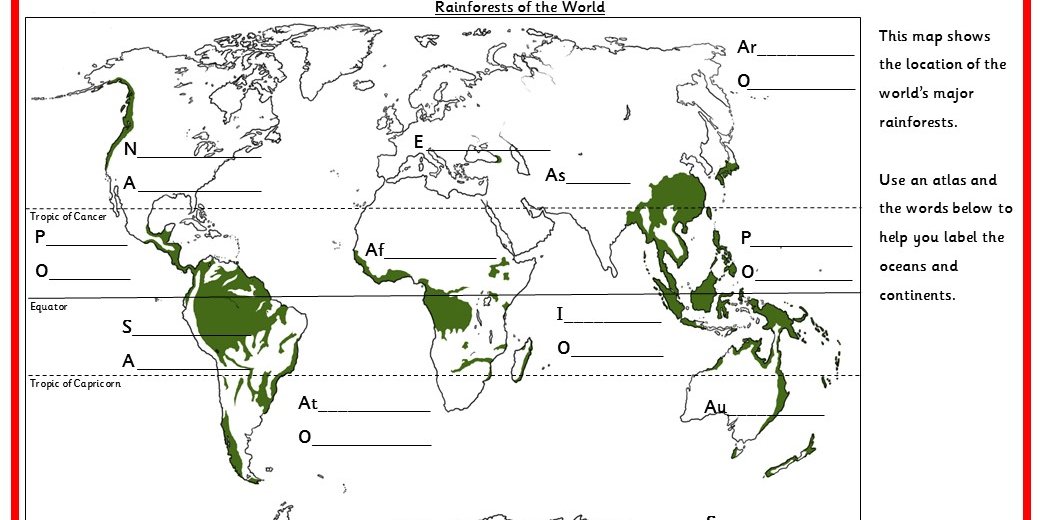

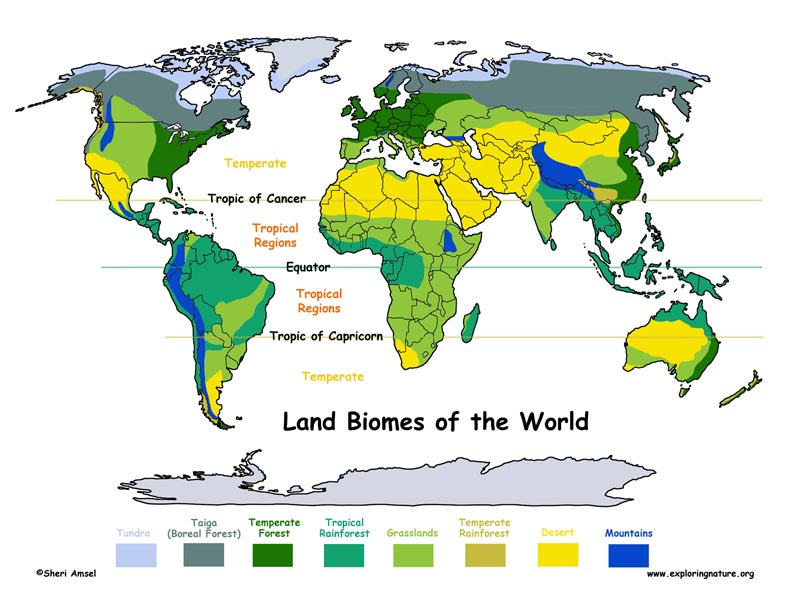

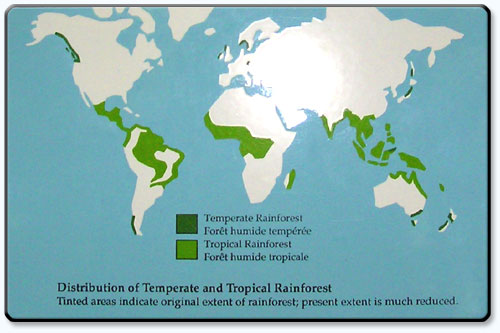

Tropics – Wikipedia – Study in China 2023

Tropics (from other Greek τροπικός κύκλος – turning circle) – climatic zones of the Earth [ source not specified 715 days ] . Since the angle of 23°26′14″ is the angle of inclination of the Earth’s axis of rotation, in a strictly geographical sense, the tropics are located between the Tropic of Capricorn (Southern Tropic) and the Tropic of Cancer (Northern Tropic) — the main parallels located at 23°26′14″ (or 23.43722°) south and north of the equator and defining the greatest latitude at which the Sun can rise to its zenith at noon. On the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, the Sun is at its zenith only once a year: on the day of the summer solstice and on the day of the winter solstice, respectively. At all intermediate latitudes, the Sun at noon is at the zenith 2 times a year, once during the annual movement to the north and the second time – to the south.

Tropics on the map of the planet

Noon in the tropics: the shadow under the palm tree indicates the presence of the sun at its zenith

Tropical regions are characterized by a hot climate.

The opposite of the tropic is the polar circle, where the latitude is (90°- 23°26′14″ = 66°33′46″).

The tropics make up 40% of the earth’s surface and contain 36% of the earth’s land [1] . In 2014, 40% of the world’s population lived in this region, and the number is projected to increase by another 10% by 2050 [2] .

Contents

Show / Hide

Seasons and climate

Main articles: Tropical climate and Rainy season

Many tropical areas have dry and wet seasons. The wet season, or rainy season, or green season, is the time of the year, which can last from one month or more, when the largest part of the average annual rainfall in the region [3] falls.

Ecosystems

Tropical plants and animals are species that grow and live, respectively, in the tropics. Tropical ecosystems may consist of tropical rainforests, seasonal rainforests, dry (often deciduous) forests, spiny forests, deserts, and other types of habitats. There is a large biological diversity of species, as well as endemics. Some examples of important ecosystems of biodiversity and high endemism include the El Yunque Rainforest Reserve, Puerto Rico, the rainforests of Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the Amazon rainforest areas in several South American countries, the dry forests of Madagascar, the Waterberge Biosphere Reserve in South Africa and tropical forests of eastern Madagascar. Often, rainforest soils are depleted, making them even more vulnerable to slash-and-burn deforestation practices, which are sometimes part of shifting agricultural cropping systems.

There is a large biological diversity of species, as well as endemics. Some examples of important ecosystems of biodiversity and high endemism include the El Yunque Rainforest Reserve, Puerto Rico, the rainforests of Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the Amazon rainforest areas in several South American countries, the dry forests of Madagascar, the Waterberge Biosphere Reserve in South Africa and tropical forests of eastern Madagascar. Often, rainforest soils are depleted, making them even more vulnerable to slash-and-burn deforestation practices, which are sometimes part of shifting agricultural cropping systems.

Literature

- Tropical zone // Great Soviet Encyclopedia: in 66 volumes (65 volumes and 1 additional) / ch. ed. O. Yu. Schmidt. – M. : Soviet Encyclopedia, 1926-1947.

- Tropics // Great Russian Encyclopedia: [in 35 volumes] / ch. ed. Yu. S. Osipov. – M. : Great Russian Encyclopedia, 2004-2017.

See also

- Tropical climate

- Tropical belt

- Subtropical

- Tropical year

- Tropical diseases

Notes

- ↑ National Geographic Society.

tropics (English) . National Geographic Society (January 21, 2011). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived 24 November 2020.

tropics (English) . National Geographic Society (January 21, 2011). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived 24 November 2020. - ↑ Allie Wilkinson. Jun. 29, 2014, 8:30 am. Expanding tropics will play greater global role, report predicts . Science | AAAS (29June 2014). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Rainy season (undefined) . Glossary of Meteorology (2009). (Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived February 18, 2012.

#Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Wiki (Study in China) is an independent company and has no affiliation with Wikimedia Foundation.

Related topics

Scientists have named a new danger of tropical hurricanes in the Atlantic

https://ria.ru/201

/1552082697.html RIA Novosti, 03/25/2019

Scientists have named a new danger of tropical hurricanes in the Atlantic

2019-03-25T13: 03

2019-03-25T13: 03

2019-03-25T13: 03

Science

USA

USA

Atlantic Ocean

Global warming 9000

Caribino sea

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21 .img.ria.ru/images/155208/23/1552082363_0:155:3092:1894_1920x0_80_0_0_415b7ab71aa2ef5abef6a2fba070be68.jpg

MOSCOW, March 25 – RIA Novosti. The most powerful hurricanes in the tropical latitudes of the Atlantic not only cause enormous economic damage, but also have an extremely negative impact on the state of forests on the islands of the Caribbean Sea and on the coast of America. In the future, natural disasters will become the main threat to their existence, scientists write in the journal Nature Communications. In the past three years, the most powerful hurricanes regularly hit the coast of North America, causing enormous economic damage to coastal cities and towns in America and causing great problems for the populations of some rare animals, such as monarch butterflies. In August and September 2017 alone, four most powerful hurricanes of the fourth and fifth categories of danger arose in the Atlantic at once: Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria, which left Puerto Rico without electricity and created a potentially catastrophic situation on the Atlantic coast USA and Mexico. In addition to the destruction, which takes tens of billions of dollars to eliminate every year, such whirlwinds have an extremely negative impact on the ecosystems of the Caribbean and Central America, destroying colonies of rare species of animals and plants. For example, the 2016 hurricanes killed about half of the monarch butterflies that wintered in Mexico. Assessing the state of the island after the Maria swept through and past, less powerful storms, Uriarte and her colleagues found that the destructive effect of hurricanes will affect not only rare species of plants and animals , but also all forest ecosystems in general.

In the past three years, the most powerful hurricanes regularly hit the coast of North America, causing enormous economic damage to coastal cities and towns in America and causing great problems for the populations of some rare animals, such as monarch butterflies. In August and September 2017 alone, four most powerful hurricanes of the fourth and fifth categories of danger arose in the Atlantic at once: Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria, which left Puerto Rico without electricity and created a potentially catastrophic situation on the Atlantic coast USA and Mexico. In addition to the destruction, which takes tens of billions of dollars to eliminate every year, such whirlwinds have an extremely negative impact on the ecosystems of the Caribbean and Central America, destroying colonies of rare species of animals and plants. For example, the 2016 hurricanes killed about half of the monarch butterflies that wintered in Mexico. Assessing the state of the island after the Maria swept through and past, less powerful storms, Uriarte and her colleagues found that the destructive effect of hurricanes will affect not only rare species of plants and animals , but also all forest ecosystems in general. For this, scientists went to the El Yunque reserve, located near San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. Ecologists have been observing its flora and fauna for more than three decades, which allowed the Uriarte team to compare its current state with what the island’s forests looked like after hurricanes Hugo and George in 1989 and 1998. As it turned out, “Maria” was much more destructive than her two predecessors: she destroyed and seriously damaged two and three times more trees than hurricanes of the third category of danger. At the same time, the elements affected the forests in an extremely uneven way – some tree species were not actually affected, while others were almost completely destroyed. Among the first were those types of palms, whose low height and high flexibility protect against strong gusts of wind, as well as cecrops, distant relatives of nettles , unable to resist the action of storms, but at the same time growing rapidly after they end. Most of all, “Maria” damaged trees, in which wood has a high density and strength, for which they are especially valued in the woodworking industry.

For this, scientists went to the El Yunque reserve, located near San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. Ecologists have been observing its flora and fauna for more than three decades, which allowed the Uriarte team to compare its current state with what the island’s forests looked like after hurricanes Hugo and George in 1989 and 1998. As it turned out, “Maria” was much more destructive than her two predecessors: she destroyed and seriously damaged two and three times more trees than hurricanes of the third category of danger. At the same time, the elements affected the forests in an extremely uneven way – some tree species were not actually affected, while others were almost completely destroyed. Among the first were those types of palms, whose low height and high flexibility protect against strong gusts of wind, as well as cecrops, distant relatives of nettles , unable to resist the action of storms, but at the same time growing rapidly after they end. Most of all, “Maria” damaged trees, in which wood has a high density and strength, for which they are especially valued in the woodworking industry. In general, the hurricane destroyed 12 times more of these representatives of the flora than other species. Their disappearance, as Uriarte notes, will not only lead to massive environmental changes and a decrease in the number of animals that need such plants, but also to the fact that the tropics will not absorb carbon dioxide and release it. This will accelerate global warming and make hurricanes even more destructive, scientists conclude.

In general, the hurricane destroyed 12 times more of these representatives of the flora than other species. Their disappearance, as Uriarte notes, will not only lead to massive environmental changes and a decrease in the number of animals that need such plants, but also to the fact that the tropics will not absorb carbon dioxide and release it. This will accelerate global warming and make hurricanes even more destructive, scientists conclude.

https://ria.ru/20180606/1522200057.html

https://ria.ru/20170916/1504869141.html

USA

Atlantic Ocean

9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 5

4.7

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acblog.xdlkab09

2019

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA Today

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og. xn--p1ai/Awards /

xn--p1ai/Awards /

News

en-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96

0009

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards09

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA “Russia Today”

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn-p1ai /awards/

ecology, usa, atlantic ocean, climate, global warming, caribbean

Science, Ecology, USA, Atlantic Ocean, Climate, Global warming, Caribbean Sea

MOSCOW, March 25 – RIA Novosti . The most powerful hurricanes in the tropical latitudes of the Atlantic not only cause enormous economic damage, but also have an extremely negative impact on the state of forests on the islands of the Caribbean Sea and on the coast of America. In the future, natural disasters will become the main threat to their existence, scientists write in the journal Nature Communications.

In the future, natural disasters will become the main threat to their existence, scientists write in the journal Nature Communications.

“What happened in Puerto Rico is a forecast for the future. Hurricanes will destroy more and more trees – everything that protected them in the past from the destructive force of the elements is no longer effective. The area of \u200b\u200bforests will shrink, they will become smaller and smaller diverse, as they will not have time to recover,” said Maria Uriarte of Columbia University in New York (USA).

In the last three years, the most powerful hurricanes regularly hit the coast of North America, causing huge economic damage to coastal cities and towns in America and causing great problems for the populations of some rare animals, such as monarch butterflies.

In August and September 2017 alone, four of the most powerful hurricanes of the fourth and fifth categories of danger arose in the Atlantic at once: Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria, which left Puerto Rico without electricity and created a potentially catastrophic situation on Atlantic coast of the USA and Mexico.

June 6, 2018, 20:00Science

Scientists have figured out why hurricanes are becoming more destructive rare species of animals and plants. For example, the 2016 hurricanes killed about half of the monarch butterflies that wintered in Mexico.

Assessing the state of the island after the passing “Maria” and past, less powerful storms, Uriarte and her colleagues found that the destructive effect of hurricanes will affect not only rare species of plants and animals, but also all forest ecosystems in general.

To do this, the scientists went to the El Yunque nature reserve, located near San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. Ecologists have been observing its flora and fauna for more than three decades, which allowed the Uriarte team to compare its current state with what the island’s forests looked like after hurricanes Hugo and George in 1989 and 1998.

As it turns out, “Maria” was much more destructive than its two predecessors: it destroyed and seriously damaged two and three times more trees than Category III hurricanes.

25 mile to the trailhead. The trail ascends to the peak of El Toro, the highest peak in the forest, where it connects with the El Toro Trail.

25 mile to the trailhead. The trail ascends to the peak of El Toro, the highest peak in the forest, where it connects with the El Toro Trail. tropics (English) . National Geographic Society (January 21, 2011). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived 24 November 2020.

tropics (English) . National Geographic Society (January 21, 2011). Retrieved 23 November 2020. Archived 24 November 2020.