History of music and dance: Music and Dance | Encyclopedia.com

Music and Dance

Quick Reference

Literature | Painting

| Music | Architecture

Glossary of Musical Terms

The following section details the major innovations in both music and dance.

Composers and instuments are listed where applicable.

ORIGINS

Music. The earliest forms of music were the

improvised rhythms of pre-historic man. They probably had a magical or spiritual

meaning and were found in rituals and ceremonies up to the fall of the Roman

Empire.

Instruments: Flute, drum, harp, trumpet,

lyre.

Dance. As with music, dance started out as

a ritual. It portrayed the hunt (by costumed figures), preparation for war,

fertility rites and so on.

THE MIDDLE AGES (400-1300)

Music. The middle ages saw the invention

of plainsong and polyphony, the musical scale by Pope Gregory I (540-604)

and a system of writing music by Guido d’Arezzo (980-1050). Minstrels and

troubadours emerged during the 11th century.

Instruments: Recorder, organ, bagpipes.

Dance. The first organised dances were processional

Court dances. By the 12th century these had progressed to couples dancing

alone. The Pavane was probably the first stylized dance.

RENAISSANCE (1300-1600)

Music. Mostly polyphonic church music.

Harmonics and instrumental music emerged along with national styles in open-air

pageants and theatre.

Instruments: Harpsichord, lute, guitar, violin

family, bassoon.

Dance. Early renaissance dances were: danse

basse (low gliding steps) and hault danse (high fast steps). A European

dance manual was published in 1416 and the first ballet performed in 1489.

Beginning of the clog dance. First printed account of a ballet, 1581.

BAROQUE (1600-1750)

Music A period of great operatic works, the

first true opera written by Monteverdi, 1607. Naples later became the centre

of operatic development. In France and Britain the spread of opera was hampered

In France and Britain the spread of opera was hampered

by the strength of court (chamber) music. Instrumental music became

much more popular. The baroque period saw the first appearance of

a full orchestra performing concertos, sonatas and symphonies. Polyphonic

music at its height.

Instruments: Oboe, french horn.

Composers: Monteverdi, Purcell, Vivaldi,

Bach, Handel.

Dance. Ballet masquerade with its hideous

and ornate masks bekame very popular. The main baroque dances were the mazurka,

jigs, saraband, chaconne, gavotte and minuet. The waltz, derived from

the minuet, was condemned as evil in England. A popular book was the ‘English

Dancing Master’ written by Playford in 1651. The five classical ballet positions

were codified.

CLASSICAL (1750-1800)

Music. The symphony is symbolic of the classical

style. Composed initially with 3 movements (fast-slow-fast) this had developed

by the end of the 18th century into 4 movements (fast-slow-fast-fast). Early

Early

symphonies were relatively short but later composers produced long and very

complex pieces. Church music became less popular, string quartets more popular

and opera less serious.

Instruments: Clarinet, piano.

Composers: Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven.

Dance. The beginning of the movement to away

from formal dance and towards free expression. Ballet became more physical,

dances now included pirouettes and leaps. Masques were removed.

ROMANTIC (1800-1900)

Music. A break away from formal composition.

Great symphonies and concertos and the height of the piano virtuoso. Opera

had less set pieces and became more continuous. In Italy there was a move

away from classical themes and towards more realistic subjects. From the

mid 19th century onwards came brass bands, operetta and music hall. Beginnings

of the blues and musicals in the late 19th Century.

Instruments: Harp, saxophone, tuba.

Composers: Early Romantic: Beethoven, Paganini,

Schubert, Mendelssohn. High Romantic: Liszt, Wagner, Verdi, Brahms, Tchaikovsky,

Grieg.

Dance. Dancing became more professional both

in the court and theatre. Ballet abandoned Greek mythology and dancers were

on points for the first time. Introduction of the square dance, can-can,

polka and the great waltzes.

The Modernists. Post romantic movement in

the 1900’s writing dreamlike and expressive music.

Composers: Puccini, Debussy, Strauss, Ravel,

Elgar.

20th CENTURY

Music. The 20th century has seen the spread

of many generic styles such as: rock, country and western, folk, soul, reggae

and so on. The birth of popular music (pop) is said to have began in the

fifties with rock and roll, a style derived from rhythm and blues and aimed

directly at the young. Such is the variety of popular music it is now almost

impossible to categorize all of its forms.

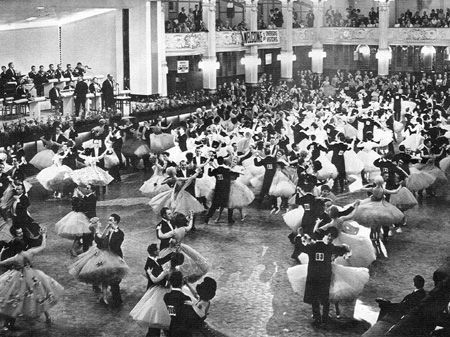

Dance. Russian ballet introduced to the west.

Beginning of free dance incorporating international styles. Ballroom dancing

widespread, many dances with Latin-American origins such as the samba, tango

and rumba. Also new were the two-step and foxtrot. The tap dance was introduced

in 1920. Modern free dance began in the fifties with Rock and Roll, the

dance styles often following the music charts.

Print this page

The History of Dance Music

It takes only one look at the grandeur of today’s electronic music culture to see that dance music has never been bigger or more celebrated than it is now. The scale of its stadium-quivering events, the numerous dance-dominated charts and the hundreds of millions of ecstatic fans make it hard to imagine the times when dance music was nothing more than a small dot in a stubborn world that didn’t want to embrace change at first.

So how could something so small and initially insignificant have grown into a booming industry against the odds? And who so bravely put the pieces together, drastically changing the course of music evolution? Read on for an eventful roller coaster ride through the history of dance music.

DISCO MUSIC

There are so many moments that could be cited as the first steps of electronic music, from the launch of Robert Moog’s first commercial synthesizer in 1964 to the dub artists of Jamaica, who started overlapping multiple tracks on reel-to-reel audio tape recorders in the ‘60s to create a fresh offshoot of reggae. But all things considered, the one thing that truly kicked off club culture was disco.

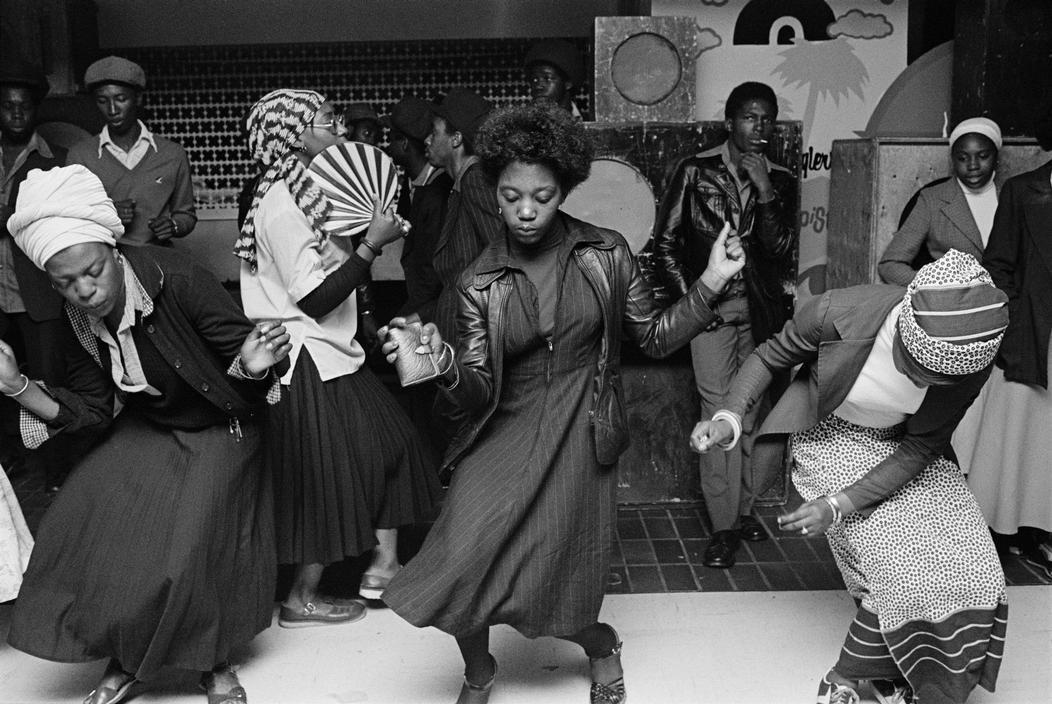

It’s no mere coincidence that disco music is rooted deep in African-American music culture. Almost every style of popular music in the twentieth century started off as black dance music, from jazz and R&B to rock ‘n’ roll, funk, hip-hop and eventually techno and house. Perhaps more so than their Western counterparts, most non-Western cultures have long been inseparable from music. Dancing to the rhythm of the drums and vocal chants was an important part of rituals, as well as a form of expression nothing else could come close to. And when the United States officially did away with slavery in 1865, the descendants of the African peoples who were transported to the States over the course of multiple centuries started to influence the country’s main music culture.

Ultimately, Disco music came to see the light of day in the mid-1960s to celebrate newly won freedoms, especially those of gay people. And although disco wasn’t as inherently electronic as most dance music styles are today, it did provide the spark that shifted the record industry’s focus from radio to dance floors.

HOUSE MUSIC

Even though it shared a headspace with disco in terms of rhythm, intensity and danceability, house music started to take over when the world became fed up with disco near the end of the ‘70s. Visionaries such as Frankie Knuckles (who started mixing up a variety of musical styles at Chicago night club The Warehouse), Jesse Saunders and Farley Jackmaster Funk laid the foundations of house music, with Farley Jackmaster Funk’s cover of Isaac Hayes’ ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ becoming the first international house hit.

Another figurehead of the first wave of house producers was Marshall Jefferson, whose style became synonymous with Chicago house. He tied the now trademark vocals, thumping piano and strings to the minimal, energetic rhythms whilst adopting a slightly faster tempo (bpm – beats per minute) than its New York counterpart. House music soon flourished across the United States, even more so when the demand for dance-floor-oriented tracks built a fire under the world of electronic equipment. By the mid-80s, the rise of drum machines, synthesizers and samplers had caused a whole world of new possibilities to open up, and house music thrived greatly in the slipstream of these technological developments.

He tied the now trademark vocals, thumping piano and strings to the minimal, energetic rhythms whilst adopting a slightly faster tempo (bpm – beats per minute) than its New York counterpart. House music soon flourished across the United States, even more so when the demand for dance-floor-oriented tracks built a fire under the world of electronic equipment. By the mid-80s, the rise of drum machines, synthesizers and samplers had caused a whole world of new possibilities to open up, and house music thrived greatly in the slipstream of these technological developments.

TECHNO MUSIC

In another American city, the evolution of music took a different turn. A new, less conventional style of electronic music popped up in the late ‘80s, and it was aptly called “techno” to reference the technologically evolved city it originates from: Detroit. It came to reflect the underlying socio-economic differences within the city, as the oil crisis of the ‘70s caused many people to lose their jobs in Detroit’s automotive industry.

The ones who played a fundamental part in the rise of Detroit Techno were The Belleville Three: Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson. The high school friends, who were black students in a predominantly white neighborhood in the suburbs of Detroit, connected over a mutual love for sports and, most importantly, the new wave of synthesizer music coming from Europe. Their music became the soundtrack for the youths whose parents had been working side by side to secure a better future for the next generations until they lost their jobs.

After Juan Atkins set up his Metroplex label in 1985 and used it to send off his early techno hit ‘No Ufo’s’ under his Model 500 moniker, Derrick May followed suit with his Transmat label in 1986 and started releasing seminal techno tracks like ‘Nude Photo’ and ‘Strings Of Life’ as Rhythim Is Rhythim. Kevin Saunderson, who also garnered huge success later on as Inner City and E-Dancer, launched his label KMS (which stands for Kevin Maurice Saunderson) in 1987, and that label has been a massive presence in the world of techno to this day.

TRANCE MUSIC

In the early and mid-‘90s, after history shows a brief and localized surge of hardcore and “gabber” music coming from the Netherlands, trance music slowly crept to the surface as a minor sub genre within the house spectrum. It shared traits with house, techno, new age and synthesizer pop, of which the latter two gave it most of its dreamy ambience.

It wasn’t a tremendous success off the bat, mostly because there wasn’t enough new material being made to warrant complete trance sets or devoted trance nights. But that all changed when tracks from the likes of Robert Miles (‘Children’), BBE (‘Seven Days And One Week’) and Sash (‘Encore Une Fois’) transcended those limitations. As these records became huge club hits and crossed over into the mainstream charts, more and more producers began to deep-dive into the world of trance, helping the genre claim a spot alongside the other great dance music styles of that time.

Spurred onward by the melodic tendencies of Ferry Corsten, DJ Tiësto and later Armin van Buuren, trance music gradually developed into the newest dominant style of dance music. Armin van Buuren became the first of the three to fully exploit the reach of the Internet. His A State Of Trance radio show, which was launched in 2001 and remained a mostly national show for its first four years, suddenly rose to global importance when a U.K. company called Radio Department snatched up the show and started broadcasting it worldwide. The globalization of dance music, and in particular trance, proved a huge turning point.

Armin van Buuren became the first of the three to fully exploit the reach of the Internet. His A State Of Trance radio show, which was launched in 2001 and remained a mostly national show for its first four years, suddenly rose to global importance when a U.K. company called Radio Department snatched up the show and started broadcasting it worldwide. The globalization of dance music, and in particular trance, proved a huge turning point.

A JUMP FORWARD

After the rise of trance, the evolution of dance music can be best described as a feedback loop. New dance music genres sprouted left and right, front and center, from hardstyle, progressive (house) and big room to drum ‘n’ bass, dubstep and pretty much every spinoff of a main genre that comes to mind. And as more and more flavors of electronically produced music tickled the taste buds of so many people across the globe, the dance music industry saw this incredible window of opportunity for what it was: a way to break the dwindling supremacy of the more traditional styles of music and build an empire of their own.

In the past ten to twenty years or so, the rise of dance music has proven to be consistently meteoric and self-amplifying. Dance music’s most prominent artists now sell out stadium shows in a heartbeat, initially small labels have become premier world brands and the long-outdated views on music consumption got swept along with the tide. And as the industry continues to innovate off the back of more technological advancement, the circle is drawn to completion.

Dance music is taking all the steps to continue its streak of dominance. But in the end, no one can tell what the industry will look like in ten, twenty or thirty years from now. One thing is for certain though. Against all the odds and in spite of the belittling grins of its early-day skeptics, dance music has managed to become a major force in the world of music. And thanks to the brave individuals that pushed onward against the stream and made their dreams reality, dance music now stands tall and proud like an electronic giant.

Source list

– How The Netherlands Took The Lead In Electronic Music Culture – Mark van Bergen

– Mary Go Wild – Gert van Veen, Arne van Terphoven

– Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, The History Of The Disc Jockey – Bill Brewster, Frank Broughton

– This Is Our House: House Music, Cultural Spaces, And Technologies – Hillegonda C. Rietveld

– The Underground Is Massive. How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America – Michaelangelo Matos

– Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture – Simon Reynolds

– Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture – Simon Reynolds

Header image credits

© Bill Bernstein – https://www.billbernstein.com/…

New Music By DMTL, Mahalo, Dombreksy, Andrew Rayel, Luke Bond, Saje & Chill Executive Officier Vol. 2

Read

Dance and dance music. History of emergence and development

Dance in Ancient Greece

Like the emergence of cave painting, the initial purpose of the appearance of dances was to accompany ancient rituals. The first dance lessons became part of the initiation rites. At the same time, the subconscious desire for pleasure has never been alien to dancing. This was largely facilitated by repetitive movements, which (in combination with the rhythm of tambourines and other ancient percussion instruments) were able to bring the dancers into an ecstatic state.

The first dance lessons became part of the initiation rites. At the same time, the subconscious desire for pleasure has never been alien to dancing. This was largely facilitated by repetitive movements, which (in combination with the rhythm of tambourines and other ancient percussion instruments) were able to bring the dancers into an ecstatic state.

Being the basis of dance, rhythm is also the formative element of music. Thus, the general rhythmic principle initially connected music (and singing) with dance. Since ancient times, both types of art have been an integral part of magical rituals.

In most ancient civilizations, dancing in front of an image or sculpture of a deity was an important part of the temple ceremony. So, in ancient Egypt, priests and priestesses (accompanied by harps and trumpets) performed movements illustrating cosmological subjects. For this purpose, there were special “rhythms of the day” and “rhythms of the night.” During the funeral, with the help of certain movements, women had to express the state of grief. In part, this was reminiscent of the plots of the paintings with “mourners” (groups of women who were charged with the duty to mourn the dead noble Egyptians, including the pharaoh himself).

In part, this was reminiscent of the plots of the paintings with “mourners” (groups of women who were charged with the duty to mourn the dead noble Egyptians, including the pharaoh himself).

In ancient history, starting from the 8th century BC, the Olympic Games were opened by dancing virgins in the temple. Such a dance (performed in a circle in honor of a deity) was originally shoros (choros). From the 6th century BC, it became the culmination of performance in the Greek theater.

In India, descriptions of the regulated hand movements of priestesses in Hindu temples are found in documents dating back to the first century AD. At the same time, each gesture had a fairly precise and subtle meaning. Dances based on them are still found today in the performance of highly qualified artists. In a certain sense, such a tradition could be attributed to sign language.

Anyone who has taken part in a fast dance knows how much the pulse quickens. In combination with alcohol, it can greatly excite the body. A similar effect has been known since ancient times, as evidenced, in particular, by the Dionysian dances of Ancient Greece. At the end of the harvest, the villagers held festivities (often escalating into drunken orgies) in honor of the god of wine, Dionysus (or his Roman counterpart, Bacchus). The trampling of grapes is one of the most common plots of images on Greek vases, and extreme forms of excited consciousness (leading even to murders) are immortalized in the tragedies (Bacchae) of Euripides.

A similar effect has been known since ancient times, as evidenced, in particular, by the Dionysian dances of Ancient Greece. At the end of the harvest, the villagers held festivities (often escalating into drunken orgies) in honor of the god of wine, Dionysus (or his Roman counterpart, Bacchus). The trampling of grapes is one of the most common plots of images on Greek vases, and extreme forms of excited consciousness (leading even to murders) are immortalized in the tragedies (Bacchae) of Euripides.

The erotic element of dancing has also existed since antiquity. Starting from 1400 BC, on the walls of Egyptian tombs there are images of half-naked dancing girls in the company of musicians. According to the plot, they were supposed to please men during their journey to the afterlife. But, the plots of the afterlife reflected the realities of the earth, so it is quite acceptable to assume the opposite correspondence.

Dancing was one of the favorite forms of entertainment in France and Italy during the Renaissance. Regular celebrations, accompanied by dancing, were strongly encouraged by Catherine de Medici after she married the French king. In 1581, the director of organizing court festivities at the royal court created the Ballet Comique de la Reine, which often included dance numbers in performances. Surviving descriptions present them as “geometric figures of people dancing together.” These events are associated with the birth of a dramatic ballet action.

Regular celebrations, accompanied by dancing, were strongly encouraged by Catherine de Medici after she married the French king. In 1581, the director of organizing court festivities at the royal court created the Ballet Comique de la Reine, which often included dance numbers in performances. Surviving descriptions present them as “geometric figures of people dancing together.” These events are associated with the birth of a dramatic ballet action.

The passion for dancing continued in France and Italy well into the 17th century. They were regularly arranged in Turin at the court of the Savoy dynasty. In France, Louis XIII (son of Marie de Medici) loved dance performances. Historical evidence draws attention to the fact that the king preferred to portray exclusively comedic characters, dressing up: an itinerant musician, a Dutch captain, a grotesque warrior, a peasant, and even a woman. His son, Louis XIV also encouraged dancing, but in their classical tradition. The characters of theatrical performances acted as protagonists of Bacchantes, ancient heroes, etc. In 1661, on the royal initiative, the Academy of Dances was organized. The undertaking turned out to be successful, and soon, in 1669after her, the Royal Academy of Music was organized. Later, both institutions were merged into the Paris Opera. That’s right, music and dance traditions coexist in France to this day.

In 1661, on the royal initiative, the Academy of Dances was organized. The undertaking turned out to be successful, and soon, in 1669after her, the Royal Academy of Music was organized. Later, both institutions were merged into the Paris Opera. That’s right, music and dance traditions coexist in France to this day.

An interesting and important stage in the ballet and musical traditions was associated with the work of JB Lully. Then, for the first time, a system for determining steps during dance (ballet) numbers was developed (or recorded). A performance with numbers created according to this system was held with great success in 1681. Soon, the virtuoso dances of men became one of the most spectacular attractions of the ballet. Between 1691 to 1710, their performance at the Paris Opera was demonstrated by Jean Ballon (Vallon). A distinctive feature of the dancer’s skill was the ability to “suspend” slightly in the air during the jump.

The further development of dance and dance music has consistently developed the traditions that have developed over the previous centuries. It was not until the 20th century that the changes came to light with the advent of the mass entertainment industry. Its result was a rapid increase in the number of dance schools and studios, as well as dance floors. However, issues of culture and aesthetics left the dance no less quickly, retaining only the desire for its sports and entertainment component.

It was not until the 20th century that the changes came to light with the advent of the mass entertainment industry. Its result was a rapid increase in the number of dance schools and studios, as well as dance floors. However, issues of culture and aesthetics left the dance no less quickly, retaining only the desire for its sports and entertainment component.

Dance music | Vvedenskaya side

What is dance music? The definition of this concept is very simple – this is music invented or performed in order to dance to it. Dance music includes many variations from waltz to tango, from disco to rock music.

Dance cannot be imagined without music. Many centuries ago, dances could be seen both in rural squares, where peasants circled to the sounds of home-made instruments, and in magnificent palace halls, where they danced to the accompaniment of trumpets, viols, and an orchestra. Music and dance brought people together. Most of the old dances in one form or another have survived to our time. Of course, they are very different from each other depending on the country in which they were born, on the time when this happened, and on who performed them and where. Over time, based on dance rhythms, musical compositions created specifically for listening appeared. These are instrumental pieces, separate parts of classical sonatas and symphonies. Dance music is widely used in opera and ballet is based on it.

Of course, they are very different from each other depending on the country in which they were born, on the time when this happened, and on who performed them and where. Over time, based on dance rhythms, musical compositions created specifically for listening appeared. These are instrumental pieces, separate parts of classical sonatas and symphonies. Dance music is widely used in opera and ballet is based on it.

The history of dance music goes back many thousands of years. Dancing in ancient times was a matter of paramount importance. Primitive people, accompanied by the simplest percussion instruments, built it with the usual order of hunting or fighting, turning to spirits and demons for help. Its wide distribution in the countries of the ancient world can be judged on the basis of mythology, sculptural and graphic, as well as a few written musical monuments.

The main leaders of the Greek dance were the gods – Apollo and Dionysus. Apollo patronized the nine muses who patronized various arts. Among them was the muse of dance – Terpsichore. Dionysus was revered as the god of winemaking, fertility, the god of creative nature. He was always accompanied by a motley and noisy retinue, dancing frantically. Apollo was honored by aristocrats, he was considered the embodiment of harmony. And Dionysus was more revered by the common people.

Among them was the muse of dance – Terpsichore. Dionysus was revered as the god of winemaking, fertility, the god of creative nature. He was always accompanied by a motley and noisy retinue, dancing frantically. Apollo was honored by aristocrats, he was considered the embodiment of harmony. And Dionysus was more revered by the common people.

In the Middle Ages, dance continued to live both among the people and in aristocratic circles. Itinerant actors dedicated their lives to dancing, each country having its own name. In France – jugglers, in Germany – shpilmans, in Rus’ – buffoons. They wandered all over Europe, amusing the audience with dances, songs, playing musical instruments. At the court of Mikhail Romanov, the dancer Ivan Lodygin even received a salary for teaching “dances and all sorts of fun.” He was the first dance teacher in Rus’.

A fertile time for the heyday of dance was the Renaissance. Since the beginning of the Renaissance, movements in the dance were constantly connected in a new way, the dancer had to not only perform them separately, but also firmly remember how they follow each other.

In 1463 the most prominent dance teacher Guglielmo Ebreo wrote a Treatise on the Art of Dance. In his book, he describes in detail the festivities that have gained wide popularity, tells dancers how to coordinate movements with music, and gives useful advice to musicians who would like to compose music for dancing. He writes about the commonwealth of music and dance and about what great opportunities this commonwealth has: it helps to perform dances of any people in their own manner, as well as “compose dances according to their imagination and talent.”

The most common dances in Europe in the 16th century were the pavane and the galliard. Pavane is an ancient dance of Spanish origin, which also existed in Italy and other European countries. Translated from Latin means “peacock”, “pava”, this dance procession was performed solemnly and proudly. Strict movements – steps, turns, bows – were in harmony with the splendor of the costumes. The ladies were wearing long dresses with trains, tall pointed hats. On gentlemen? – raincoats, swords and unusual shoes with long, bent like a bird’s beak, noses. After the pavane, the galliard (from Italian means “peppy”) was often performed – a three-beat dance with light jumps. In Italy, “competitions” were held at balls for the best performance of the galliard. Pavane and galliard were not only dances, but also instrumental pieces. In music collections, the galliard has always followed the pavane. This is how the old two-part suites appeared, written for the lute, a favorite European musical instrument. In the 17th century, the pavane and galliard gradually give way to the suite allemande and courante, sarabande and jig. These dances formed the four-movement cycle of the ancient suite (suite in French means “sequence”). The pieces followed each other in a certain order and were connected according to the principle of contrast: slow and moving.

On gentlemen? – raincoats, swords and unusual shoes with long, bent like a bird’s beak, noses. After the pavane, the galliard (from Italian means “peppy”) was often performed – a three-beat dance with light jumps. In Italy, “competitions” were held at balls for the best performance of the galliard. Pavane and galliard were not only dances, but also instrumental pieces. In music collections, the galliard has always followed the pavane. This is how the old two-part suites appeared, written for the lute, a favorite European musical instrument. In the 17th century, the pavane and galliard gradually give way to the suite allemande and courante, sarabande and jig. These dances formed the four-movement cycle of the ancient suite (suite in French means “sequence”). The pieces followed each other in a certain order and were connected according to the principle of contrast: slow and moving.

At the beginning of the suite there was a serious, strict, unhurried allemenda. As an everyday court dance, it appeared in England, France and the Netherlands in the middle of the 16th century. The allemenda was born from the greeting signals of the trumpeters, sounding at the meeting of high persons – princes, rulers of counties and duchies. Having entered the suite, the allemenda became an introductory piece of a solemn nature.

The allemenda was born from the greeting signals of the trumpeters, sounding at the meeting of high persons – princes, rulers of counties and duchies. Having entered the suite, the allemenda became an introductory piece of a solemn nature.

The second part of the suite is the chimes, a rather lively French dance, translated as “running”, “flowing”. They danced the chimes with a smooth sliding step. The size is triple, the complex and whimsical figures of the dance are reflected in a bizarre melodic pattern.

A completely different soraband, slow, majestic, somewhat stern, even having a mournful tone. Its time signature is in three beats, with an emphasis on the second beat of the bar.

The finale of the suite is an energetic jig, a fast, unconstrained dance of English sailors. It was usually performed in pairs, and the sailors – one at a time. The jig music flows non-stop in even triplets, like a merry stream.

Gradually, composers began to include other dances in the suite: minuet, bure, gavotte, rigaudon.