Jerusalem coat of arms: Kingdom of Jerusalem Medieval Coat of Arms Digital Art by Serge Averbukh

Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem

Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem

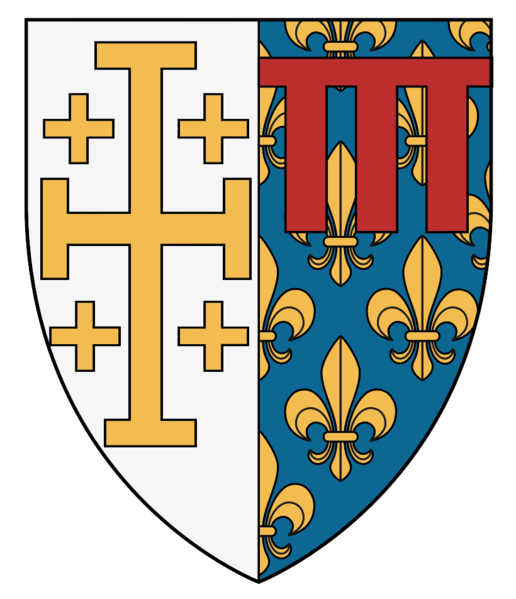

- Arms of the Kingdom

- Claimants to the Throne

- Other Crusader States

- See also heraldry in Cyprus

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was created in 1098, when the members of the

First Crusade captured Jerusalem and elected Godfrey of Boulogne, or Godefroi

de Bouillon, duke of Lower-Lorraine, as king of Jerusalem. The city was

itself finally taken back by the Muslims in 1291, although the title continued

to be claimed for centuries.

The Corpus Inscriptionum Crucesignatorum

is online, listing inscriptions from the Crusader times that have been found in the Middle East.

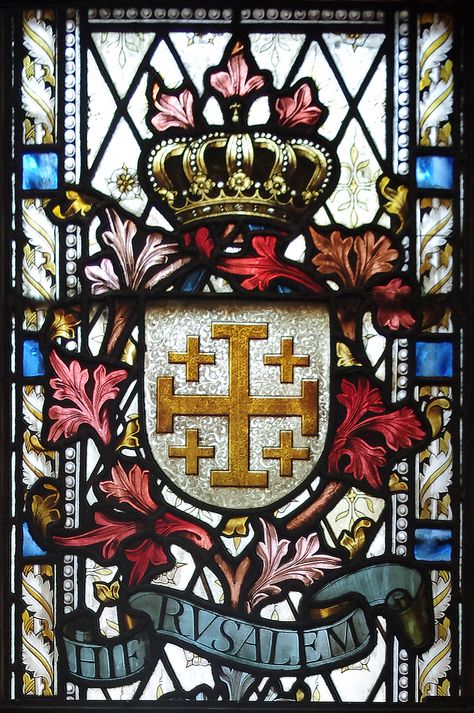

The Arms of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem are well-known: Argent a cross

potent between four crosses or. It is the most well-known violation

of the rule of tinctures.

Insignia of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre (from Diderot’s

Encyclopédie. They are A cross potent between four

crosslets gules.

Whether these arms were ever used by the kings of Jerusalem is another

matter. According to an article by Hervé Pinoteau in the Cahiers

d’Héraldique, vol. 4, the earliest representation of the cross

potents between crosslets is on the seal of a nephew and ward of John of

Brienne, king from 1210 (the seal is from 1227). The arms of Jerusalem

also appear on a reliquary called “la cassette de Saint-Louis”

which he dates to 1236. (See also an

article by Elliot Nesterman on early evidence of the Cross of Jerusalem).

The arms of Jerusalem pop up in a number of places. The reason for this

is the rather tortuous history of the throne and title. The short version

is this: three lines stemmed from Queen Isabeau (d. 1206), the eldest

of which ruled in absentia until 1268, at which time the two other

lines entered in dispute over the succession. From this dispute stems

the claims of (1) the kings of Cyprus and (2) the kings of Sicily.

The claim to Cyprus (1) became object of dispute in

1474 as the result of an usurpation: the claims of the usurper (1a) passed

to Venice, while those of the displaced ruler (1b) passed to Savoy. As

As

for the claims of the kings of Sicily (2), it became part of the dispute

in 1434 between the duke of Anjou and the king of Aragon. The claims

of the former (2a) passed briefly to the kings of France (1494-1515) and

were later resurrected by the dukes of Lorraine in 1700 (whose descendants

became emperors of Austria), while the the claims of the latter (2b) passed

along with Sicily itself to the kings of Spain (1506-1700), then becoming

the object of yet another dispute until returning to a younger son of

the king of Spain in 1738; henceforth the title was used both by the

kings of Spain and those of the Two Sicilies.

The kingdom of Jerusalem was founded as a consequence of the 1st crusade

of 1099. Godefroi de Bouillon died in 1100 and was succeeded by his brother Baudoin

I (+ 1118) and a great-nephew Baudoin II (+ 1131), who left an eldest daughter

Mélissende. She passed the throne to her husband Foulques d’Anjou

(+ 1147), and to her sons Baudoin III (+ 1163) and Amaury or Amalric (+

1173). Amaury had a son and successor Baudoin IV (d. 1185), and two daughters,

Amaury had a son and successor Baudoin IV (d. 1185), and two daughters,

Sybille and Isabeau (1169-1206).

Sybille married in 1176 William of Montferrat (+ 1177), by whom she had

a posthumous son Baudoin. She was then married in 1180 to Guy de Lusignan (d. 1194),

count of Jaffa and Ascalon who was also appointed regent of the kingdom

by the invalid Baudoin IV. But Baudoin

IV then changed his mind, took away the regency, and abdicated in 1182

in favor of Sybille’s son Baudoin V. This child died in 1186, soon after

his uncle, and Sybille became queen of Jerusalem, and was crowned with

her husband Guy de Lusignan. However, a rival in the person of Conrad of

Montferrat, brother of Sybille’s first husband, rose up. In the end an

agreement was reached: Guy would retain the title for his life, Conrad

would marry Sybille’s sister Isabeau and succeed as well as his posterity.

By that time, the city itself had actually been lost. Sybille had died

in 1190, Conrad was murdered in 1192, leaving only a daughter Marie (1191-1212),

and Guy renounced his claim in 1192 and bought the island of Cyprus from Richard

Lionheart who had just conquered it from the Byzantine empire.

This left only Isabeau as the heir, and she became queen in 1192. All

subsequent claims to the throne of Jerusalem stem from her. She

married the same year Henri de Champagne (1166-97), who became king with her and

died in 1197, leaving two daughters Alix and Philippa. Queen Isabeau

next married Amaury de Lusignan (1145-1205),

elder brother of Guy and his successor as king of Cyprus, by whom she had Sybille

(married to Leo II of Armenia) and

Mélissande. Isabeau died in 1205 and was succeeded by her

eldest daughter Marie (1191-1212), married to Jean de Brienne (d. 1237) in 1209.

Their only daughter Isabeau (1211-28) was married to the Emperor Frederic II who forced his parents-in-law

to turn over the throne to him in 1225. Frederic was succeeded as Emperor

and king of Jerusalem by his only child of that marriage, Conrad (1228-54),

himself succeeded by his only child Conradin of Hohenstaufen 1252-68),

who lost his throne of Naples and his life to Charles of Anjou.

With him the issue of queen Isabeau’s first daughter died out.

The Hohenstaufens were ruling in absentia, and their rule was not liked.

The local barons managed to induce various people to claim the regency.

Alix de Brienne, second daughter of queen Isabeau, had married Hughes

de Lusignan (d. 1218), son of Amaury by a previous wife, and king of Cyprus.

Alix died in 1246 and her son Henri (1218-53) succeeded her as regent of Jerusalem.

At his death, his son grandson Hugues II (1252-67) was a minor and the widow

Plaisance (d. 1261) was regent of both Cyprus and Jerusalem. At her death,

a new regent was required; the late king Henri had two sisters Marie (d. 1252)

married to Gauthier de Brienne, and Isabelle (d. 1264), married to Henri de Poitiers.

The elder one’s son, Hugues de Brienne, was passed over in favor of the younger one’s son Hugues d’Antioche as

regent of Cyprus, while Isabelle herself was accepted as regent for Jerusalem.

On her death in 1267, Hugues de Brienne’s attempt to claim his rights was

rebuffed and the throne of Cyprus, along with the regency of Jerusalem,

passed to Hugues d’Antioche, whose descendants assumed the name of Lusignan and

reigned over Cyprus.

At the death of Conradin, the issue of Queen Isabeau’s eldest daughter

became extinct. Hugues III of Cyprus, descended from her second daughter

and already regent, now claimed the throne. But another claim emerged through

the third daughter of Queen Isabeau, Mélissende,

who married Bohémond IV of Antioch (uncle of Hugues III) and whose

only daughter Marie of Antioch claimed the throne as being closer in kinship to

Isabeau. She was unsuccessful and Hugues III was crowned king of Jerusalem in

1269. She went to Rome to plead her case with the Pope, and was eventually

induced to cede her rights in 1277 to Charles of Anjou, whom the pope had

established as king of Naples and Sicily (the same who

had defeated Conradin in 1268). Henceforth there were two lines of claimants,

the kings of Cyprus and the kings of Naples.

The kings of Cyprus continued to be crowned kings of Jerusalem, although from

1277 to 1282 the remnants of the kingdom (Acre) were actually under

Charles d’Anjou’s control, and the kings of Cyprus only gradually restored

their authority. But soon after, with the fall of Acre in 1291,

But soon after, with the fall of Acre in 1291,

there was nothing left of the kingdom of Jerusalem.

In 1458 Jean III, last male of the line, died without male heirs.

His only sister Anne had (d. 1462) married Louis I de Savoie. His only daughter Charlotte (d. 1487)

was recognized as queen of Cyprus, Armenia and Jerusalem, and married to

her first cousin Louis de Savoie. But she was dethroned

in 1460 by a bastard son of her father, namely Jacques II (d. 1473), and fled to Italy.

Ultimately, in 1485, she ceded her rights to her husband’s nephew Charles I, duke

of Savoie, and his successors; at that point the dukes of Savoie (later

kings of Sardinia and kings of Italy) added the title of king of Jerusalem,

Cyprus and Armenia to their titles and the arms to their achievement. The

kings of Italy used the title until 1946.

Jacques II died in 1473, leaving a widow Caterina Cornero (1454-1510), from the

Venitian aristocracy. His posthumous son Jacques III soon died. The city

of Venice turned Cyprus into a protectorate, and, in 1489, forced Caterina

Cornero to return to Venice and cede her rights to the Republic. From then

From then

on, the Republic of Venice also added the title and arms of Jerusalem,

Cyprus and Armenia to its own, until 1797 when the Republic was abolished

and its territories handed over to Austria by the Treaty of Campo-Formio.

Cyprus was under Venetian control until 1571 when it was conquered by the

Turks. Venice became part of the kingdom of Italy in 1866.

Meanwhile, the kings of Sicily also claimed the title of king of Jerusalem.

In 1282, Charles d’Anjou lost Sicily and his descendants reigned in Naples

only (albeit under the title of kings of Sicily) while Sicily itself was

ruled by branches of the house of Aragon.

When the descendants of Charles d’Anjou became extinct in 1434, the two claimants were

René d’Anjou and Alfonso, king of Aragon and Sicily, and the latter

won, at which point his successors the kings of both Sicilies added the claim

of Jerusalem to their own. Ren’s claim was resurrected by his grand-nephew

king Charles VIII of France in 1494, who managed to conquer and briefly hold

Naples, and who used the title of Jerusalem, as did his successor Louis XII

(but no other French king did so). In 1506 the Two Sicilies was finally

In 1506 the Two Sicilies was finally

regained by king Ferdinand of Aragon, and henceforth possessed, along

with the claim to Jerusalem, by the kings of Spain, descendants of

Fernando’s daughter Juana and her husband Philip of Habsburg, until

their extinction in male line in 1700.

As a result of the war of Spanish Succession (1701-13), Naples and Sicily

were ceded by Spain to the Habsburg emperor Charles VI in 1720, and

the pope duly invested the emperor with the titles of king of Sicily

and Jerusalem on June 5, 1722 (the kingdom being a papal fief). In the

course of the war of Polish

Succession (1733-38), the younger son of the king of Spain, Don Carlos,

managed to conquer the Two Sicilies, a conquest recognized by the peace

of Vienna of 1738, and by the pope in the same year. Carlos became

king of Spain in 1759 and left Naples and Sicily to his younger son

Ferdinand, whose descendants reigned until 1860. The kings of Spain

continued to use the title of Jerusalem until 1931, as did the kings of Two-Sicilies.

On the other hand, René’s daughter Yolande married Ferry de Vaudémont,

one of whose sons became duke of Lorraine. The modern house of Lorraine

took up the claim to Jerusalem in 1700 (although it wasn’t the best

claimant from a genealogical point of view, as pointed out by W. A. Reitwiesner) when duke Leopold returned to

his duchy after 28 years of French occupation, and adopted a closed royal

crown and the style of king of Jerusalem. His son François, duke of

Lorraine, married the Empress Maria-Theresa, and their descendants as

rulers of Austria inherited the claim. The arms of Jerusalem could be seen in the grand arms

of State of the Austrian Empire in the 19th century and the title was used

until 1918.

There is very little evidence on the arms of the Crusader states. The

traditional arms of the kingdom of Jerusalem are not known before the

1230s, when the city had already been lost. Numismatic evidence is scant,

epigraphic evidence even more so (there are very little heraldic traces

of the Crusaders in the Middle East, outside Cyprus; see an

interesting exception).

Numismatic evidence

The best work is Gustave

Schlumberger’s Numismatique de l’Orient Latin (Paris, 1878; reprint Graz 1954).

In a coin auction catalogue I recently received, coins from Tripoli feature:

- Obverse: horse with cross above, Reverse: a cross between four roundels

(bronze, Raymond II 1137-52) - Obv: cross patty, Rev: eight-point star (Bohemond VI, 1251-75, silver gros)

- Obv: cross slightly patty, Rev: three-towered castle (Bohemond VII, 1275-87,

silver gros)

I believe the 8-pt star was a recurrent motif on Tripoli coins.

Coins of Antioch feature:

- Raymond Roupen (1216-19): helmeted head between crescent and 5-pt star, Rev:

cross patty with crescent in one quarter.

(coins from early 12th c. have a bust of St Peter and inscriptions, or the

Mother of God facing nimbate).

Interestingly, coins from Cyprus (1306-1473) constantly feature on the reverse a

cross potent between four crosses, never crosslets but sometimes patty or formy.

But what is peculiar is that the main cross is “quadrat in the centre”, that is,

its center is thickened by a square. This is, according to Parker’s Glossary,

called a cross of S. Chad, because it features in the arms of the see of

Lichfield and Coventry, of which S. Chad was the first bishop. The quadrating

on the Cyprus coins is much less pronounced than in the drawing in Parker, but

this is nevertheless quite intriguing.

Other evidence

- monuments (carved arms, epitaphs, etc): two or three epitaphs with arms are

known; some graffiti carved on marble columns of the church of the Nativity in

Bethleem were made by 14th-15th c. pilgrims. That’s all that survived. One

notable exception: the

tomb of Philippe d’Aubigni in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. - Monuments in the West: Marguerite, daughter of Louis d’Acre, vicomte de

Beaumont, himself son of Jean de Brienne, king of Jerusalem, was married to

Bohemond VII, count of Tripoli (d. 1287) and eldest son of Bohemond VI,

last prince of Antioch. She died in France in 1328, and her tomb in the

She died in France in 1328, and her tomb in the

abbey of Maubuisson was described as “parsemée de croix de Jérusalem

dans des losanges de gueules, et de lions rampants dans des losanges de sable

fleurdelisés” in Du Cange’s Familles d’Outremer (Paris, 1869, p. 486).

The tomb was destroyed in 1793 (reference to Dulaure, Environs de Paris,

vol. 2, p. 331, n. 2, which I have not checked). - objects: a handful survive, mainly from Cyprus.

- seals: Gustave Schlumberger’s Sigillographie de l’Orient Latin (Paris, 1943)

is probably quite comprehensive, and there is little heraldry to glean from it.

Lots of seals of the kings of Jerusalem, princes of Antioch, counts of Tripoli

are known, but they bear no arms. See for example the seals of

Baudoin II (1118-31),

Amalric (1162-75),

Jean de Brienne (1212-37).

In Antioch, Raymond of Poitiers (1136-49) is

shown riding a horse and bearing a cross on his shield and banner, but that’s

it. Among lesser barons, the Ibelin family, lords of Arsur and Beyrut

apparently had “Or a cross patty gules”. The device certainly appears on their

The device certainly appears on their

shields and banners as shown on their seals. Aside from that, there are arms

here and there: Hugues de Giblet (Biblos) has a 8-pointed star, the Porcellet

family has a boar passant, the lordship of Loron or Thoron was a lion rampant.

There is more armory from Cyprus and Constantinople; but then, those arms are

well known. The Courtenay arms appear on Philippe de Courtenay’s seal (d.

1283). Interestingly, the earlier emperors of Constantinople, Baudoin of

Flanders (d. 1205), Henri I (d. 1216), Baudoin II (d. 1261) all use the lion of

Flanders, although one contemporary cronicler describes Henri riding in battle

with a coat-armour gules semy of crosses or. Villehardouin, princes of Achaia,

use the family arms of a cross recercelee; later, Louis a cadet of Burgundy who

claimed Achaia added a quarter of Villehardouin to his arms of Burgundy ancient

(14th c.). Achaia was also claimed by a junior branch of Savoy, who differenced

with a bend.

Heraldry and The Crusades, part 3. The Arms of Jerusalem – Heraldic Jewelry

QUEENS COLLEGE ARMS

No Coat of Arms from the time of the Crusades are more reverently regarded than those of the crusader’s Kingdom of Jerusalem, which consists of five crosses. The central one is a large cross ‘potent”, or crutch shaped, and it is surrounded by four small plain crosses, one in each corner of the shield. All crosses are gold upon a silver shield which is one of the rare exceptions to the rule in Heraldry whereby a metal object may not lay upon a metal field in the Coat of Arms. It is thought that the violation was intentional due to the specials sacredness of the Arms of Jerusalem. There are various schools of thought as to the meaning of the Arms of Jerusalem, some writers see in the form of the central cross a combination of the letters ‘I” and “H” standing for Iesus (Jesus) and Hierusalem (Jerusalem). The number of crosses has also been thought to represent the Five Wounds of Christ; but the most probable theory is that the crosses symbolize the Savior, Jesus and the four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The reference to Jerusalem in the Psalms may have been the reason for the metal upon metal design of the Coat of Arms:

The reference to Jerusalem in the Psalms may have been the reason for the metal upon metal design of the Coat of Arms:

“Though ye have lien among the pots

Yet shall ye be as the wings of a dove

Covered with silver and her feathers with gold”

To modern minds this may seem like a stretch however it must be remembered that in the Middle Ages much importance was attached to the prophetic interpretations of the scriptures; and it may well be that the designers of the Arms of Jerusalem had this text in mind, and felt they were assisting in its fulfillment.

ARMS OF JERUSALEM

.

ARMS OF THE SEE OF LICHFIELD

The close resemblance between the Arms of Jerusalem and those of the See of Lichfield are too close to be merely a coincidence. In the Lichfield Arms the central cross is squared at the center, and the four small crosses are of the form known as “paty”. The field is divided vertically in red and silver, and the crosses are counterchanges, silver on the red background and red on the silver background. An early Bishop of Lichfield is believed to have assumed this Coat of Arms after a journey to Jerusalem; but as the patron of the Cathedral is St. Chad ( a 7th century Bishop of Mercia), the Arms have come to be incorrectly associated with him.

An early Bishop of Lichfield is believed to have assumed this Coat of Arms after a journey to Jerusalem; but as the patron of the Cathedral is St. Chad ( a 7th century Bishop of Mercia), the Arms have come to be incorrectly associated with him.

They were deflected still further from their true significance when they became the basis of the Arms of the family of Chad, baronets from the 18th century. The Arms of Jerusalem are quartered in the shield of Queens’ College Cambridge, founded by Henry VI’s Queen, Margaret of Anjou, daughter of the landless King of Naples and Jerusalem; and the Arms of Lichfield have been embodied in the shields of Selwyn College, Cambridge; Denstone College, Derbyshire and other foundations linked in some way with the Diocese of Lichfield.

Coat of arms of Jerusalem – | Articles on tourism from votpusk.ru

Coat of arms of Jerusalem – | Articles on tourism from votpusk.ru

Top 7 best

spa hotels in Russia

Top 7 best

spa hotels in Russia

3639 views

0 like

share

Vkontakte

Odnoklassniki

Copy

Interesting

- Jerusalem

- Map of Jerusalem

- Photos of Jerusalem

What else to read?

- Where is the Dead Sea located?

- Flag of Israel

- New Year in Israel

- Tours to Eilat

- Treatment in Israel

- What to bring from Israel

- Resorts in Israel

- Airports in Israel

- Holidays in Eilat

- Holidays in Israel in February

All articles

The center of faith on the planet, undoubtedly, is this small Israeli city, where adherents of different religions rush all year round. It is also in the focus of attention of tourists who do not belong to any of the world’s confessions, but who seek to get acquainted with ancient monuments and shrines. The coat of arms of Jerusalem is the main symbol of the city.

It is also in the focus of attention of tourists who do not belong to any of the world’s confessions, but who seek to get acquainted with ancient monuments and shrines. The coat of arms of Jerusalem is the main symbol of the city.

At the same time, it is the emblem of the municipality, which can tell a lot to the initiate in the secrets of history. The coat of arms was adopted in 1950 after a competition among designers. The author is Eliyahu Koren, a well-known book designer in Israel, who works in one of the departments of the Jewish National Fund.

Description of the coat of arms of the holy city

Stylishness of the Jerusalem coat of arms is the first thing that is noted by those who see the main heraldic symbol of the city. It looks especially good on a color photo, since the palette, on the one hand, is very simple, only two colors are used, on the other, it looks quite harmonious. The coat of arms of Jerusalem features several major and minor elements that play their part, including:

- a lion, turned to the right, standing on its hind legs;

- two olive branches framing the protagonist;

- brick wall in the background;

- inscription in Hebrew – the name of the city.

The wall symbolizes the Old City, the historical center of Jerusalem, now divided into four quarters, corresponding to the main world religions. This is not just a brick fence, but a kind of reference to one of the most famous Israeli cultural and historical sights, the so-called Western Wall.

Olive branches, forming a symbolic wreath surrounding a lion, are important heraldic symbols. They are used in the images of coats of arms, flags, heraldic signs of many states of the planet and famous families. On the coat of arms of Jerusalem – the olive means the desire for peace, the establishment of balance on the planet, the balance between religions and beliefs.

Excursions in Jerusalem

Holy places in Jerusalem. History of the three world religions

Touch the ancient relics and understand the meaning of the Holy Land for the whole world

Explore Jerusalem in 3 hours

Saturated walk through the northern or southern part of the city with immersion in its ancient history

All Jerusalem on foot

Big sightseeing tour of the main attractions of the city

Holy places in Jerusalem. History of the three world religions

History of the three world religions

Touch the ancient relics and understand the meaning of the Holy Land for the whole world

Explore Jerusalem in 3 hours

Saturated walk through the northern or southern part of the city with immersion in its ancient history

All Jerusalem on foot

Big sightseeing tour of the main sights of the city

show more

Lion of Judea – the main symbol

Terrible and predatory animal has long been used in world heraldry. But for the Jews it has a special meaning. The lion is one of the main symbols of Judaism, a representative of one of the twelve tribes, from which, according to beliefs, the Jews originated.

In addition, the lion is associated with the biblical Judas (Yehuda), who was called the “young lion”. The tribe of Judah was one of the most powerful ancient Israeli families, so the appearance of this particular animal on the official emblem of Jerusalem is deeply symbolic.

Olga Sokolova

All articles by the author

Like this article?

Subscribe to our channel and don’t miss new articles!

Our channel in Yandex Zen

Interesting

- Jerusalem

- Map of Israel

- Map of Jerusalem

- Photos of Jerusalem

What else to read?

- Where is the Dead Sea located?

- Flag of Israel

- New Year in Israel

- Tours to Eilat

- Treatment in Israel

- What to bring from Israel

- Resorts in Israel

- Airports in Israel

- Holidays in Eilat

- Holidays in Israel in February

All articles

Categories of Jerusalem

- How to get there

- religious

- Events

- Leisure

- hiking

- bars

- Excursion rest

- Pilgrimage

- Christianity

- New Year’s and Christmas

- Where to go in summer

Attractions

Jerusalem

All attractions

Hotels

Jerusalem

All hotels

Discount tours

to Jerusalem

All tours

Getting to Jerusalem on your own

From

Popular articles

All articles

Vkontakte

Odnoklassniki

Copy

Arms of the Kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem

Arms of the Kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem

Heraldic

website of Sergey Panasenko

Author

site Russian artist Sergey

Petrovich Panasenko (Mikhalkin).

Born in the city of Astrakhan at 1970

year. In 1977-1979 he lived in

Krabozavodsk (Shikotan Island,

Kuril Islands, Sakhalin

region). In 1989 he graduated

Astrakhan art

College named after Pavel Alekseevich

Vlasov (Astrakhan, AHU imp. P. A.

Vlasov). Since 1990 he has been living in Moscow.

Painted over 850 paintings and performed

more than 10500 graphic works.

S. P. Panasenko seriously studies

art history (preferably

“small Dutch”, Biedermeier,

Wanderers, Pre-Raphaelites, early

impressionists and realist

European painting

mid-late 19th century) and history

(heraldry, genealogy,

sphragistics, chronology,

historical geography,

source study). In art

adheres to realistic

directions. With your creativity

contributes to the revival and

development of classical

Russian painting, and

Russian and Eastern European

heraldry. The site is divided into

several parts: painting (in

art gallery

compositions, portraits, still lifes and

landscapes), coats of arms (state,

territorial, ecclesiastical and

family heraldry, laws

Russian Empire on coats of arms),

genealogy (lists of noblemen

surnames, family trees) and

science articles.

Coats of arms

kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem.

Dynasty de Lusignan.

(Article published

in No. 84 of 2005 of the magazine “Herboved”).

Extended

electronic version of the article

preparing for publication on the site.

Illustrations.

1. Coat of arms of Hugo X lord de

Lusignan (de Lusignan) Comte de La Marche (de

La Marche).

2. Coat of arms of Hugo VI lord de

Lusignan (de Lusignan).

3. Coat of arms on the gravestone of Emer

(Aimer) de Valence Bishop

Winchester (reconstruction), XIII century.

4. Coat of arms of the Seigneurs de Lezay.

5. Arms of the Comtes de La Marche (de La

Marche). Flemish manuscript

Flemish manuscript

(“Chifflet-Prinet Roll”), 1297

6. Arms of Aymer de Valens

(Aymer de Valance) Earl of Pembroke.

Manuscript of the Carlaverock Poem, 1300

(the same coat of arms in Falkirk

manuscripts, 1298 years). Similar coat of arms

William de Wales Earl of Pembroke

(Walford manuscript, ca. 1273;

Camden manuscript, c. 1280).

7. Coat of arms of William de Valens

Earl of Pembroke on his tombstone in

Westminster, 1296

8. Coat of arms of John Hastings, 1308

9. Arms of the Earl of Pembroke, 1418. Rod

Hastings succeeded the Lusignans

(de Valens) their coat of arms and title of Earls

Pembroke.

10. Coat of arms of Hugo III lord de

Partenay. Walford manuscript, c.

1273

11. Coat of arms of the kings of Cyprus,

middle of the fifteenth century. stone slab in

Colossus. Cyprus.

12. Coat of arms of the kings of Cyprus (Cipern). v.

Coat of arms of the kings of Cyprus (Cipern). v.

Solis. “Wappenbuchlein”. 1555

13. Coat of arms of the kings of Cyprus.

Camden manuscript, c. 1280

14. Coat of arms of King Jacques I of Cyprus and

Jerusalem (coat of arms of the King of Cyprus),

1370-1386 Similar coat of arms

used by kings Amory II (1197 y.) and

Hugo IV (depicted on the plate).

15. Coat of arms of Levon de Lusignan

King of Armenia (Cilicia). “Armorial de

Gelre”. 1370-1386

16. Coat of arms of the King of Cyprus.

Walford manuscript, c. 1273

17. Coat of arms of Prince Hugo de Lusignan

Galilee. Armorial de Gelre. 1370-1386

18. Coat of arms of the kings of Cyprus. So

coat of arms used by kings Hugo IV

(depicted on the plate) and Hugo III (X), c.

1273 and 1265-1288

19. Coat of arms of the Constable

Jerusalem. Armorial of Vermandois,

Armorial of Vermandois,

1280-1300

20. Coat of arms of João Infante

Portuguese, Duke de Coimbra.

21. Coat of arms of Guy (Guido) de Lusignan,

King of Cyprus (authenticity of the coat of arms

is doubtful).

22. Coat of arms of Jerusalem. Mathieu

(Matthew) Parisian. “Story

England”, 1244

23. Coat of arms of Jerusalem. Mathieu

(Matthew) Parisian. “Story

England”, 1244

24. Coat of arms of the kings of Jerusalem.

One of the plates of the Cypriot King Hugo

IV, XIV century.

25. Coat of arms of the kings of Jerusalem.

The coat of arms used by the kings

Baldwin I, John I (“Le Roy d’Acre” in

Walford manuscript, c. 1273),

Peter (Pierre) I and Hugo III.

26. Coat of arms of the kings of Jerusalem.

Zurich armorial, ca. 1370

27. Coat of arms of the “patriarch”

Coat of arms of the “patriarch”

Jerusalem”. Armorial “Van den

Ersten”, about 1380

28. Arms of Louis II (d. 1417) Duke

Angevin and King of Sicily (coat of arms

kings of Sicily). 1370-1386

Blanca has a similar coat of arms (d. 1310),

daughters of the Neapolitan king

Carlo II.

29. Coat of arms of the kings of Jerusalem.

Codex Bergsgammar, c. 1435.

A similar coat of arms in the Herbovnik

Vermandois, 1280-1300

30. Coat of arms of Duke Gottfried

Bouillon, king of Jerusalem.

Armorial de Gelre. 1370-1386

31. Coat of arms of the kingdom

Jerusalem (Jerusalem). V. Solis. “Wappenbuchlein”,

1555

32. Flag of one of the participants

crusade. Miniature XVI (?)

century.

33. Coat of arms of the kings of Jerusalem.

Armorial of Konrad Grunenberg, 1483

g. (“Austrian Chronicle”?, 1480

G.).

34.

-HartmannSchedel.jpg) She died in France in 1328, and her tomb in the

She died in France in 1328, and her tomb in the The device certainly appears on their

The device certainly appears on their