Miguel enriquez corsario: Corsario puertorriqueo y Pirata Cofres-Puerto Rico-datos y fotos

Miguel Enríquez recibe la Medalla de la Real Efigie (12 marzo 1712) – España en la historia

Miguel Enríquez

Miguel Enríquez fue

uno de los personajes extraordinarios que produjo el Imperio Español. Nacido en

1674, en San Juan de Puerto Rico, fruto de los amores de Graciana Enríquez,

esclava negra liberada y de padre blanco desconocido, su familia era de lo más

pobre. Sin embargo el Imperio le ofreció la posibilidad de medrar y subir en el

escalón social de forma estratosférica. Si el destino le hubiera hecho nacer en

el Imperio Británico, un mulato, de padre desconocido, no hubiera tenido la más

mínima posibilidad de escalar en la sociedad de la época, por muchos apoyos y

estudios que tuviera. Sin embargo, Miguel, no solo logró amasar una fortuna, si

no que llegó a enviar cartas al rey de España. Veamos como sucedió.

Su padre, es una

incógnita histórica, pero lo cierto es que fue escolarizado y aprendió a

escribir en forma suficiente como para poder redactar documentos complejos.

Alguien tuvo que pagar esas “misas’ y no pudo ser su madre. Su padre a buen

seguro estuvo vigilante y aportó capital. Sin embargo, en aquellos tiempos, a

temprana edad se debía ser capaz de sobrevivir y Miguel a los diez años era

aprendiz de zapatero. Y así estuvo hasta los 16, cuando ingresó en el ejército,

cosa bastante habitual en aquellos tiempos. Durante 10 años, mantuvo su

ocupación principal de zapatero, con su servicio al ejército, y poco sabemos de

sus actividades, pero en 1700 ocurrió algo.

Este algo pudo

terminar con su carrera definitivamente, ya que se le acusó de vender

contrabando en su casa. Enríquez fue condenado a un año de trabajos forzados en

el Castillo San Felipe del Morro y se le impuso una multa de 100 piezas de

ocho. No recurrió. Pagó la multa y solicitó cambiar la sentencia por un servicio

en el Cuerpo de Guarnición de Elite de artillería. No parece muy probable que

con las ganancias como zapatero, pudiera pagar todo. Más bien se presume que

las ganancias como contrabandista fueran bastante pingues o que su padre

siguiera ayudándole en la sombra.

Al año siguiente cambió

su suerte. En 1701, llegó el nuevo gobernador Gutierrez de la Riva, con la

orden directa de evaluar el costo de construir un buque diseñado para finalizar

con el comercio de extranjeros que amenazaban la economía de la zona. No se

sabe la razón, pero desde el primer momento, Enríquez trabajó a las órdenes de

Gutierrez y consiguió que en 1704 se iniciara la construcción de la nave y que

el apareciera como responsable de la operación, que consistía en hacer el corso

sobre las naves extranjeras y repartir el botín entre la Corona Española y los

socios del barco. La operación tuvo un gran éxito y Enríquez pasó de zapatero y

contrabandista a comerciante influyente y corsario.

En el servicio a la Corona, se convirtió en el corsario más agresivo de Puerto Rico, siendo mencionado en una carta de 1705, elogiando el trabajo realizado. EL rey Felipe V, elogió su actividad y de paso reclamó las armas capturadas a las víctimas. Enríquez operaba con dos buques, pero estos eran repuestos rápidamente en el caso de perdida por captura o naufragio. No eran barcos pequeños y mantenía tripulaciones entre 100 y 200 marinos por buque.

No eran barcos pequeños y mantenía tripulaciones entre 100 y 200 marinos por buque.

Diez años mas tarde de su paso como condenado por el Castillo del Morro, Enríquez recibía el nombramiento oficial de Capitán de Mar y Guerra y era el personaje más activo en la defensa de Puerto Rico, no solo porque su flote garantizaba la defensa de la zona, sino porque además era prestatario del gobierno en caso de destrozos causados por tormentas y tifones. Era el principal proveedor de víveres y suministros militares de Puerto Rico e indispensable para el gobierno de la isla. Ello le empezó a provocar la inquina de las clases altas de la sociedad insular, como era de esperar. Sin embargo el nuevo gobernador Danio, escribió a Felipe V solicitando un reconocimiento honorifico de sus logros. Después de consulta con el Consejo de Indias, el 12 de marzo de 1712 se le concedió la Medalla de la Efigie Real y se le nombró caballero. Nada mal como logro, para un mulato de padre desconocido.

Pero la situación había

empezado a cambiar un año antes con la llegada de un nuevo gobernador. Juan de

Ribera. Con este se iniciaron una serie de acontecimientos que se repitieron

durante muchos años. Podrían escribirse decenas de series televisivas con todas

las intrigas que se repitieron a la llegada de nuevos gobernadores. A pesar de

la inquina de la alta sociedad local, Enríquez logró mantenerse y acrecentar su

fortuna y fue más bien el cambio de la política internacional y el fin del

corso en el Atlántico, que llevó a la decadencia de Enríquez.

Acusado de contrabando a gran escala, en 1735 se refugia en el Convento de Santo Tomas para evitar ser encarcelado en El Morro. Allí permaneció 8 años pero no ciertamente inactivo. Escribió hasta seis veces directamente al Rey solicitando la revisión de su caso. Nunca obtuvo respuesta y el que había sido el verdadero gobernador en la sombra durante más de veinte años, terminó sus días en una celda del monasterio, protegido por los frailes dominicos. En octubre de 1743, moría repentinamente, el que había sido el mayor propietario de Puerto Rico.

En octubre de 1743, moría repentinamente, el que había sido el mayor propietario de Puerto Rico.

Enríquez tuvo una vida

agitada y acabó en la ruina, pero si hubiera nacido en Inglaterra, nunca

hubiera salido de la miseria. El racismo del Imperio Británico le hubiera

impedido salir del hueco en que había nacido. En el denostado Imperio Español,

llegó a ser el más rico de los habitantes de las Antillas.

Manuel de Francisco Fabre

https://es.qwe.wiki/wiki/Miguel_Enríquez_(privateer)

https://www.monografias.com/docs/Biograf%C3%ADa-Miguel-Enr%C3%ADquez-PK423FYBY

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miguel_Enr%C3%ADquez_(privateer)

Apuntes sobre el racismo heredado – Categoría Cinco

María de los Ángeles Castro Arroyo

José Campeche, Ex-voto del Ataque Británico a San Juan en 1797 (detalle)

Bien sabéis que en Puerto Rico, como en casi todos los lugares de las Indias, el ser pardo es una loza sobre la cabeza, que tienen que soportar aquellos que por su infortunio nacen con esa sombría mancha…, y por tanto estoy expuesto a las reglas que los blancos, que sin ningún pudor se llaman hombres de honor, principales, distinguidos, etc.

han establecido para su personal provecho.

Miguel Enríquez

Así resumió el corsario puertorriqueño lo que significaba ser mulato en la sociedad puertorriqueña del primer tercio del siglo XVIII. El entonces hombre más rico y poderoso de la isla terminó sus días víctima de sus transgresiones en una sociedad donde el mayor baldón era ser negro o su descendiente. Fray Íñigo Abbad lo reafirmó con una frase lapidaria: “no hay cosa más afrentosa en esta Isla que ser negro o descendiente de ellos…”. Peor aún si se era mulato e hijo ilegítimo. Los epítetos que les dirigía la élite blanca – “raza infesta”, “mala raza”, “raza inferior”— recalcaban la deshumanización que se les atribuía como arma de subordinación.

La esclavitud africana fue potenciada por civilizados estados europeos como parte de una empresa económica centrada en la trata trasatlántica y la explotación de los territorios americanos. Para justificarla, se inventaron múltiples teorías, inclusive con la complicidad de la iglesia, al atribuirle al negro defectos de origen divino y otras tantas conjeturas para acreditar la imposición sobre aquellos a quienes se obligaba a realizar los duros trabajos desdeñados por los grupos blancos dominantes.

Agotada la mano de obra indígena, el trabajo esclavo prevaleció en la minería, las obras públicas, la construcción de las ciudades, el servicio doméstico, las labores manuales y en las agrícolas, sobre todo en la industria azucarera. Su tardía abolición ayudó a consolidar el estigma sobre aquellos que la habían sufrido y sus descendientes, señalados por sus rasgos físicos y su cultura. El racismo, en todas sus tonalidades y disfraces, es el más viejo y pernicioso de los males heredados de la esclavitud africana, aunque muchos niegan su existencia en la sociedad actual. La idea de que en Puerto Rico ha prevalecido la armonía interracial descansa sobre la infundada creencia de que bajo el régimen español todos convivían como una “gran familia”.

En apoyo a esa falacia, suelen destacarse casos de negros y mulatos que estamparon una huella en su momento histórico. Los ejemplos de Miguel Enríquez y José Campeche, en el siglo XVIII, y los del maestro Rafael Cordero y su hermana Celestina (también maestra, aunque menos recordada), el contratista Julián Pagani y el médico José Celso Barbosa, en el XIX, han servido en ocasiones para mostrar el indulgente prejuicio local, la tolerancia hacia el subalterno denigrado, pero olvidan que el reconocimiento a sus indudables méritos nunca llegó al punto de considerarlos semejantes a un miembro de la élite blanca.

A dos seres con vidas tan diferentes como fueron Enríquez y Campeche los igualaba ante la sociedad el ser descendientes de esclavos y su condición de mulatos. El primero enriqueció y adquirió gran poder económico mediante el contrabando; el segundo brilló como retratista y pintor de cualidades sobresalientes. Ambos tuvieron amistad con personajes de la élite y miembros del alto clero de la ciudad y vivieron entre blancos en la calle de la Cruz. Sus rostros eran agradables, sus cuerpos proporcionados y suaves sus pelos. Fueron hombres devotos, protectores de sus familias. El corsario tuvo amores e hijos de uniones libres, mientras que la vida del pintor lindaba con la monástica. Su fama trascendió los confines insulares siendo la ciudad su base de operaciones.

Antonio Martorell, “Don Miguel Enríquez (corsario del rey)”, 2021, Colección Chocolate Cortés.Ramón Atiles, Reproducción del autorretrato de José Campeche (perdido), siglo XIX

Como era usual, los dos se apropiaron de prácticas y usos de las clases altas, entre ellos la tenencia de esclavos que formaba parte del ambiente en que vivieron. Tenerlos demostraba cierto poder económico y ascenso social. Mas esto lo resentían y temían las élites blancas. Llegar a disfrutar de cierto prestigio no significaba aceptación igualitaria; se mantuvo en el plano de la condescendencia por las virtudes de cada uno. A pesar de la riqueza acumulada y los servicios prestados por Enríquez, la Corona —con la complicidad de los principales de la ciudad— se deshizo de él cuando ya no servía a sus intereses; murió solo, asilado en el convento de los dominicos, despojado de sus bienes y, quizás, envenenado. En cambio, a la hora de su muerte, Campeche tuvo el entierro que había dispuesto, con exaltaciones y evocaciones a su arte. Sin embargo, dejó pocos bienes y su hermana tuvo que suplicarle a la Corona una pensión. La fuerza de ambos atemperó el prejuicio solo hasta cierto punto. Ni siquiera la vida ejemplar del pintor y el reconocimiento a su pintura le ganó la igualdad social. Para aquella sociedad, pese a su celebridad, continuaron siendo un contrabandista y un artesano a pesar de que se destacaban sobre la elite blanca con la que convivían.

Tenerlos demostraba cierto poder económico y ascenso social. Mas esto lo resentían y temían las élites blancas. Llegar a disfrutar de cierto prestigio no significaba aceptación igualitaria; se mantuvo en el plano de la condescendencia por las virtudes de cada uno. A pesar de la riqueza acumulada y los servicios prestados por Enríquez, la Corona —con la complicidad de los principales de la ciudad— se deshizo de él cuando ya no servía a sus intereses; murió solo, asilado en el convento de los dominicos, despojado de sus bienes y, quizás, envenenado. En cambio, a la hora de su muerte, Campeche tuvo el entierro que había dispuesto, con exaltaciones y evocaciones a su arte. Sin embargo, dejó pocos bienes y su hermana tuvo que suplicarle a la Corona una pensión. La fuerza de ambos atemperó el prejuicio solo hasta cierto punto. Ni siquiera la vida ejemplar del pintor y el reconocimiento a su pintura le ganó la igualdad social. Para aquella sociedad, pese a su celebridad, continuaron siendo un contrabandista y un artesano a pesar de que se destacaban sobre la elite blanca con la que convivían.

El racismo, en todas sus tonalidades y disfraces, es el más viejo y pernicioso de los males heredados de la esclavitud africana, aunque muchos niegan su existencia en la sociedad actual.

Los fueros militares y la iglesia, opuestos al mestizaje, prohibían los matrimonios desiguales, pero no podían impedir las uniones consensuales, las relaciones sexuales libres, ni las violaciones de mujeres negras, esclavas o no, que resultaban en hijos ilegítimos, desdeñados por ser mulatos espurios. Aparte del abusivo control que les daba el poder, se trataba de una censura hipócrita, porque militares, clérigos y altos funcionarios del imperio copulaban con las mismas mujeres que despreciaban. El corsario Enríquez era probablemente hijo de un sacerdote, sin ser esto una singularidad. Hubo gobernadores notorios por sus impúdicas excursiones nocturnas e incluso quien vendió una hija mulata como esclava. El poderoso cabildo no admitía negros ni mulatos en su cuerpo. En 1806 el regidor Manuel Hernáiz tuvo que pelear el puesto que había comprado en subasta pública, impugnado porque su esposa descendía de mulatos. Tras el rechazo estaba el temor del Estado y de la élite blanca al ascenso de los mulatos y la competencia que estos podían representar a sus privilegios de clase, amén de perderlos como mano de obra en oficios mecánicos.

En 1806 el regidor Manuel Hernáiz tuvo que pelear el puesto que había comprado en subasta pública, impugnado porque su esposa descendía de mulatos. Tras el rechazo estaba el temor del Estado y de la élite blanca al ascenso de los mulatos y la competencia que estos podían representar a sus privilegios de clase, amén de perderlos como mano de obra en oficios mecánicos.

Las repercusiones que tuvo la Revolución Haitiana (1791-1804) agravaron el terror ante la gente de color. Los rumores de posibles sublevaciones esclavas y la invasión haitiana de Santo Domingo (1821-1844), exacerbaron el resquemor de los blancos principales y de las autoridades quienes actuaron para salvaguardar sus intereses. Intentaron blanquear la población mediante el fomento de la inmigración y tomaron otras precauciones extremas desplegadas en los bandos de policía y circulares que culminaron con el opresivo y cruel Bando contra la raza africana del gobernador Juan Prim en 1848. Es decir, el Estado procedía en total sintonía con los estratos dominantes, reforzando las medidas de control frente a los que podrían subvertir el orden político y social establecido. .

.

Esclavizados ajusticiando a esclavisas blancos en la Revolución Haitiana c. (Principios s. XIX)

Es difícil precisar el cumplimiento de dichos códigos, mas lo significativo es el envilecimiento de los afrodescendientes en ellos.

Por otro lado, el crecimiento desmedido de la población a lo largo del XIX generó en San Juan la aglomeración que provocó situaciones de insalubridad e incomodidad. Las estrecheces de una ciudad asentada en el extremo oeste de una isleta con topografía accidentada, amurallada, fortificada y regida por reglamentaciones militares, sin posibilidades de crecer hacia lo alto por el temor a los terremotos y las restricciones defensivas, abastecida de agua mediante aljibes, tuvo las repercusiones más visibles sobre los sectores pobres poblados mayormente por afrodescendientes. Muchos vivían en el medio de la ciudad, alquilados en estrechas habitaciones en las plantas bajas de las casas, en zaguanes o en rincones habilitados como dormitorios, pero otros muchos fueron empujados hacia los bordes que quedaban sin construir, formando barriadas señaladas, incluso por expresivos nombres como el de Culo Prieto, en el recinto norte.

Plano de la Ciudad de San Juan de Puerto Rico (1770)

Para contrarrestar el serio hacinamiento existente, las autoridades propusieron el ensanche de la ciudad con el derrumbe de las murallas, conseguido en 1897, y con el desplazamiento de la “gente sobrante y mal entretenida…”, como los tildaron en 1800 los regidores del cabildo, hacia los sectores de Puerta de Tierra y Santurce.

Mujer afrodescendiente en San Juan, c. finales del s. XIX

Desde el siglo XVI las casas de la ciudad albergaban un número variable de personas. Al núcleo familiar se unían criados, esclavos, agregados e inquilinos varios que ocupaban distintas áreas de las viviendas, según lo demuestra el padrón de 1673 ordenado por el obispo Bartolomé García de Escañuela. En el siglo XIX, con el aumento demográfico, la falta de espacios para acogerlo cambió el tono de la condescendencia comunitaria porque la aglomeración aproximaba a los diferentes componentes sociales más de lo que les gustaba a las élites que reprobaban sus conductas y la cercanía estrecha. Sobre todo, los patios comunes fueron un foco de irritación continua por los olores de sus cocinas, la algarabía, la presencia de animales sueltos y el comportamiento bullanguero que chocaban con los hábitos de las clases altas que habitaban los pisos superiores. La intolerancia y el desdén hacia ellos se acentuaron más.

Sobre todo, los patios comunes fueron un foco de irritación continua por los olores de sus cocinas, la algarabía, la presencia de animales sueltos y el comportamiento bullanguero que chocaban con los hábitos de las clases altas que habitaban los pisos superiores. La intolerancia y el desdén hacia ellos se acentuaron más.

El Consejo de Administración local, con subidos tintes segregacionistas, denunció el “repugnante aspecto de suciedad e indigencia” causado por el amontonamiento, sobre todo de gente de color, en detrimento y molestia del “resto del vecindario”.

Los remedios recomendados eran dos: “el uno de fácil e inmediata ejecución, aunque sometido a la prudencia, es eliminar la población que nada representa en la Capital, que solo perjuicios le originan; el segundo, digno de más detenido examen y más difícil en su aplicación… [por la falta de espacios] es el aumento de construcciones”.

Es decir, el Consejo insular achacaba el repulsivo panorama del hacinamiento a los pobres, por lo que había que empujarlos fuera del cerco murado hacia Puerta de Tierra y Santurce. Muchos salieron, pero otros pudieron educarse, alcanzaron cierto bienestar económico permanecieron como propietarios en calles céntricas de la urbe. El contratista negro Julián Pagani, cuyas talentosas hijas dominaban el canto e instrumentos musicales, celebraba animadas veladas en su casa, con cena y baile, a las que asistían jóvenes blancos. José Celso Barbosa ejerció la medicina, alcanzó el liderato político, fue promotor del cooperativismo y debatiente en la prensa, admirado por unos y minusvalorado e injuriado por otros. El intelectual Arturo Alfonso Schomburg llegó niño a San Juan en 1872 procedente de Saint Thomas, estudió en el Colegio de Párvulos, fue tipógrafo y publicó artículos en La Correspondencia en 1891 antes de marcharse a Nueva York ese mismo año, cuando todavía era un adolescente de 17.

Muchos salieron, pero otros pudieron educarse, alcanzaron cierto bienestar económico permanecieron como propietarios en calles céntricas de la urbe. El contratista negro Julián Pagani, cuyas talentosas hijas dominaban el canto e instrumentos musicales, celebraba animadas veladas en su casa, con cena y baile, a las que asistían jóvenes blancos. José Celso Barbosa ejerció la medicina, alcanzó el liderato político, fue promotor del cooperativismo y debatiente en la prensa, admirado por unos y minusvalorado e injuriado por otros. El intelectual Arturo Alfonso Schomburg llegó niño a San Juan en 1872 procedente de Saint Thomas, estudió en el Colegio de Párvulos, fue tipógrafo y publicó artículos en La Correspondencia en 1891 antes de marcharse a Nueva York ese mismo año, cuando todavía era un adolescente de 17.

Las biografías de estos y otros afrodescendientes magníficos demuestran sus logros, pero también las complicaciones y el detente que la etnia significó en sus vidas y el lugar que les asignó a ellos y a sus familias en el escalafón social. Sus ascensos fueron siempre hasta cierto límite y ellos combatieron ese racismo con las armas a su alcance. Enríquez lo enfrentó imponiéndose sobre las actividades contrabandistas de la elite. Ante la calidad de los retratos de Campeche, los privilegiados se avinieron a posar para él. Barbosa, sin bajar cabeza, sobrellevó el prejuicio de los jesuitas para poder educarse en el Seminario Conciliar y defendió su raza en el periódico El Tiempo, cuando creyeron insultarle llamándole negro. Schomburg alcanzó sus metas en la diáspora.

Sus ascensos fueron siempre hasta cierto límite y ellos combatieron ese racismo con las armas a su alcance. Enríquez lo enfrentó imponiéndose sobre las actividades contrabandistas de la elite. Ante la calidad de los retratos de Campeche, los privilegiados se avinieron a posar para él. Barbosa, sin bajar cabeza, sobrellevó el prejuicio de los jesuitas para poder educarse en el Seminario Conciliar y defendió su raza en el periódico El Tiempo, cuando creyeron insultarle llamándole negro. Schomburg alcanzó sus metas en la diáspora.

El prejuicio racista heredado de tiempos de la esclavitud se manifiesta hoy en un abanico de actitudes, gestos, palabras y acciones con múltiples disfraces. La dureza de los testimonios racistas en Estados Unidos, por ejemplo, choca con los nuestros porque acá se muestran de otra manera. Pero los encontramos a diario en el menosprecio, la subvaloración, el hostigamiento y la limitación de oportunidades educativas, de empleo, de ascenso social, de tener mejor calidad de vida que mantienen a un sector de los afrodescendientes puertorriqueños en los márgenes de la pobreza.

Bibliografía mínima

Baerga, María del Carmen. Negociaciones de sangre: dinámicas racializantes en el Puerto Rico decimonónico. San Juan de Puerto Rico, Ediciones Callejón, Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2015.

Barbosa, José Celso. Problema de razas. Selección y recopilación por Pilar Barbosa de Rosario, San Juan de Puerto Rico, La obra de José Celso Barbosa, 1937.

Díaz Quiñones, Arcadio. “Estudio preliminar” en Tomás Blanco, El prejuicio racial en Puerto Rico. Río Piedras, Ediciones Huracán, 1985. La primera edición es de 1942.

Díaz Soler, Luis M.. Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico. 2da ed., Río Piedras, Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1974.

El proceso abolicionista en Puerto Rico: documentos para su estudio. San Juan de Puerto Rico, Centro de Investigaciones Históricas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1974 y 1978, 2 vols.

González, Lydia Milagros. Tras las huellas del hombre y la mujer negros en la historia de Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico, Departamento de Educación, Programa de Estudios Sociales, 2005.

Tras las huellas del hombre y la mujer negros en la historia de Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico, Departamento de Educación, Programa de Estudios Sociales, 2005.

López Cantos, Ángel. Historia y poesía en la vida de Miguel Enríquez. Biografía de Miguel Enríquez en sus documentos personales (Los “papeles” del Rastro) y Raimundo Ferrer, un poeta apologista de Miguel Enríquez. San Juan de Puerto Rico, Editorial LEA, Ateneo Puertorriqueño, Cuadernos de Historia, núm. 6, 2004.

____________. Miguel Enríquez, corsario boricua del siglo XVIII. San Juan, Ediciones Puerto, 1994.

Morales Carrión, Arturo. Auge y decadencia de la trata negrera en Puerto Rico (1820-1860). San Juan, Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1978.

Naranjo, Consuelo y Miguel Ángel Puig Samper, eds. Color, raza y racialización en América y el Caribe. Madrid, Editorial Catarata, 2022.

Piqueras, José Antonio. La esclavitud en las Españas. Un lazo trasatlántico. Madrid, Ediciones Catarata, 2012.

La esclavitud en las Españas. Un lazo trasatlántico. Madrid, Ediciones Catarata, 2012.

Pizarro Santiago, Vilma. Tras la huella del negro. Los barrios intramuros y extramuros del arrabal metropolitano de finales del siglo XIX en Puerto Rico. San Juan, Publicación independiente, 2021.

Sued Badillo, Jalil y Ángel López Cantos. Puerto Rico negro. Río Piedras, Editorial Cultural, 1986.

Taylor, René et al. José Campeche y su tiempo. Catálogo de la exposición en el Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Metropolitan Museum of Art y el Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1988-1989.

On the 40th anniversary of the death of Miguel Enriquez

In October 1974, the head of the Chilean Marxist-Leninist organization MIR died in a battle with the bourgeois secret services.

Companero

que hermoso canto me ha tocado interpretar

que clara aurora cada dia veo brillar

ya mi guitarra ni una voz para dudar

solo una bala que en tu pecho nos llamo

a ti,

a mi, 9005 por esta historia sin perdon

Companero

ni por un dia te olvidaste de seguir

siempre aferrado a tu consciencia de existir

quitando cercos, trabajando de aprendiz

siempre sembrando esa alegria de vivir

en ti

en mi

en nosotros

por esta historia sin perdon

Aqui nadie muere companero

Aqui nadie cesa de luchar

Aqui nada termina companero

Aqui cada dia es continuar

Aqui se dice todo companero

De aqui saldra la luz la libertad

Aqui nadie muere companero

Aquel es el primero aqui estara

Companeros

hace ya siglos que empezo esta balacera

los mismos siglos que nos matan por monedas

la misma muerte que se aferra a nuestras venas

la mano armada de tu ejemplo hasta vivir

en ti

en mi

en nosotros

por esta historia sin perdon

por esta historia sin perdon

por esta historia sin perdon

por esta historia sin perdon

—–

,

that every day I see a bright morning dawn

but in the ringing of my guitar, in my voice suddenly notes of anxiety . ..

..

and a bullet in your chest called to you

you,

me,

us,

through this story, which is not there will be forgiveness

Compañero,

on this day you forgot to stay,

but your living consciousness tells me how to live,

removes barriers, leads a student

and sows the power to live

in you

in me

in us

through this story, which there will be no forgiveness

No one dies here Compañero

No one stops fighting here

Nothing ends here at all, buddy

Here every day continues the work

Every comrade’s word echoes here

From here comes the light of liberation

No one dies here, buddy

He comes here again , but already to be the first

Companions

of the past, started this battle.

The same time they kill us all for money.

The same death clings to us.

But in order to live, you armed with your example

you

me

us

through this story, which will not be forgiven

through this story, which will not be forgiven

through this story, which will not be forgiven . ..

..

=== =======================

(translated from Spanish. Google)

Miguel, your name is

Like a mountain stream,

That breaking from the mountains

breaks through us path.

Miguel, your eyes

look at us from the future,

your song is a song of the purest ideals,

and it hits harder than projectiles.

Miguel, your hand

did not tremble in front of the enemy,

outnumbered,

but not in spirit

Miguel Henriquez, your fighters –

with a lump in their throat,

mourn you with weapons in their hands,

with your death seeing your greatness.

I want to write a letter

engraved in gold letters:

Miguel Enriquez did not die,

he only gave his life to his homeland.

1974

(Angel Parra)

———————————

HYMN MIR (PEACE OF HUMANS will rise with MIR rifles) Patcis. Dedicated to the memory of the fallen soldiers of the organization

=======================

In memory of Miguel Enriquez

source – http://9e-maya. com/index .php?topic=4350.msg1037312#msg1037312

com/index .php?topic=4350.msg1037312#msg1037312

Tags: Latin America, heroes, historical memory, history of resistance

In memory of Miguel Enriquez Espinosa | Left radical

Chilean brothers and sisters!

I am writing to you on behalf of the women, men, children and old people of the Zapatista National Liberation Army, mostly Maya, who are fighting back in the mountains of southeastern Mexico against neo-liberalism and for the sake of humanity.

Young Chileans and Chilean women, please accept our Zapatista greetings.

We would like to thank our brothers and sisters who have given us this opportunity today to take our word to a reluctant Chile.

We ask for this word a place in your indignation, in your pain and, above all, in your hope.

I won’t tell you about us Mexican Zapatistas, about our struggles, our aspirations, our dreams, our nightmares and our resistance. After all, compared to the men and women born of your land who so brightly illuminated the skies of Latin America, we Zapatistas are but a distant and dim ray of light.

No, our word goes to you in order to unite our memory and our greetings to the Latin American and Chilean from the Left Revolutionary Movement, MIR, who fell in battle with the Pinochet dictatorship on October 5, 1974 years old.

Our word today is a greeting to Miguel Enriquez Espinosa[1].

We greet him today under the sky of that same Latin America that suffers today from the Rio Bravo[2] to Patagonia, while those in power pour a handful of ashes into our palms and say to us: “This is all that is left of your motherland.”

Today, the same as always – those who are at the top – continue to show us their version of “geography”, imposed on part of our land.

Where yesterday there was a banner, today there is a shopping center. Where there was history yesterday, there is fast food today. Where the copihue flower grew yesterday, today it is a swamp. Where yesterday there was memory, today there is oblivion. Where there was justice yesterday, there is charity today.

In place of the motherland – a pile of ruins. In place of memory are short-term solutions. In the place of freedom is a grave. In place of democracy – a commercial. Instead of reality, there are numbers.

They, those from above, tell us: “This is the future you were promised, enjoy.”

They tell us this and lie.

This future is too similar to the past. And if we look closely, maybe we can see that they, those on top, are the same as yesterday. The same ones who, like yesterday, ask us for patience, maturity, prudence, humility, capitulation. We have seen and heard all this before.

We Zapatistas remember. We take memory out of our guerrilla packs, out of our field uniform pockets. We remember.

Because there was a time when the whole of Latin America was somewhere here, right next to each other.

It was enough to reach out and the hearts of the Latin American peoples touched.

It was enough to look a little to the side – and very close at hand one could see the spreading lightning of the Amazon, the indelible scar of the Andes, the arrogant presence of the peak of Aconcagua[4], the endless Tierra del Fuego and the eternally restless Popocatepetl[5].

And with them were peoples who gave name and life to these lands.

Because there was a time when Chile and all the countries of Latin America were much closer to Mexico than the empire, which from its geographical and political north imposes distances on us, who have always felt their historical neighborhood.

There was a time.

Maybe there is still time left.

Today, as yesterday, money is the common basis for all kinds of arrogance.

Today, as yesterday, in the same ranks with the almighty transnational giants, foreign military power continues to suck the juices of our bowels, sometimes dressed in the uniforms of local armies, sometimes in the form of advisers, embassies, consulates, secret agents.

Today, as yesterday, this money is used to buy official certificates of impunity for the “gorillas” who served them, who – as we always knew – when they said “homeland” did not mean Chile, Uruguay, Argentina or Brazil. No, the flag they saluted was only a grille and muddy stars.

Today, as yesterday, the warlike and merciless north surrounds and seeks to stifle the lone star of dignity that shines in the Caribbean.

Today, as yesterday, the governments of some of our countries are helping him as extras in a shameful attempt to break the Cuban people.

Today, as yesterday, the empire that takes on the role of world policeman and destroys laws, reason and entire nations remains the same.

Today, as yesterday, the one who tries to destabilize legitimate governments for not obeying him (yesterday in Chile, today in Venezuela and always in Cuba) is the same.

Today, as yesterday, the system, built on lies, deceit, falsification and the dictatorship of money, seeks to give us lessons in democracy, freedom and justice.

Both today and yesterday, the same people “democratize” our America, that is, they bring her pain, poverty and death.

Today, as yesterday, the one who persecutes, tortures, imprisons, kills is the same.

Today, as yesterday, a war is being waged against us, sometimes with bullets, sometimes with economic programs, and always with lies.

Today, as yesterday, the real terror, the one from above, calls on God as a lawyer.

Today, just like yesterday, they try to hide from us that the god who inspires all this exists, but his real name is Money.

Today, as yesterday, the most timid and powerless part of some of our countries are their governments.

Today, as yesterday, capitulation is covered up by complex and lengthy arguments, public opinion polls, exclusive brand suits, mirrors turned inside out.

Maybe there is still time left.

Maybe not.

Because today a new and intricate outfit, in which the savagery of profit for the few is dressed at the cost of loss for the majority, is waging a real world war against humanity.

Entire countries are in ruins.

Territories are being conquered.

The geography of the planet is brought to a new order.

Boundaries for money are being torn down and new ones are being erected – for peoples.

They are trying to replace the historical cultures of our peoples with momentary vulgarity.

In some countries the place of national governments has been taken by regional governors.

Natural resources, land, history are squandered at reduced market prices; and above the mountain ranges that cut and unite America from the south of the Rio Grande[6] to Tierra del Fuego, they are trying to erect a billboard that announces, warns, threatens: “For sale.”

The poor and the dispossessed, that is, those who are the vast majority of humanity, are subject to confiscation and segregation.

Their dignity is confiscated, they are segregated on the outskirts of big cities, on the margins of government programs, in the farthest corners of the future being defined today in some countries, not in parliaments or presidential palaces, but at meetings of shareholders of transnational corporations.

Today’s exploitation is the wildest of all that has existed in the history of mankind, cynicism today is the philosophical credo of those who claim to rule the planet, that is, those who have everything but shame.

Today’s war against humanity, that is, against reason, is the most global of all that have been before in history.

Today’s war is being waged on all fronts and in all countries.

And if yesterday the struggle, opposition and resistance to the idiotic logic of gain was a moral duty, today it has simply become a matter of personal, local, regional, national, continental and worldwide survival.

Chilean brothers and sisters!

There was a time when all of Latin America was here, right next to each other.

Maybe there is still time left.

Maybe the collective memory that unites us as Latin Americans will find names and dates in the calendar to tell us, to tell us that there is a greater homeland than the one that gives us the flag.

How many names are there in the calendar of pain in our lands?

For our America, Ernesto Che Guevara is one of the names consecrating October[7]; our calendar – of those below[8] – is consecrated with the names of Turcios Lima[9] and Jon Sosa[10] in Guatemala, Roque Dalton[11] in El Salvador, Carlos Fonseca[12] in Nicaragua, Camilo Torres[13] in Colombia, Carlos Lamarck[14] and Carlos Marigella[15] in Brazil, Inti and Coco Peredo[16] in Bolivia, Raul Sendik[17] in Uruguay, Roberto Santuccio[18] in Argentina, Cesar Yañez[19] in Mexico

each in his own way decided to attach a trigger to hope, the names of those who, in addition to the share of tenderness that Latin America requires of us in order to love her, added some portion of lead … and blood … their blood.

Because all of them, all those who are a pain in our calendar, do not just leave us. On the contrary, they leave, leaving us with something like a debt, something that we must return in order to be able to call their names without shame and without sadness.

Someone says that men and women who have entered and are embarking on the path of armed struggle were or are worshipers of death, had or have a call to self-sacrifice, a desire for messianism, that they only sought to take their place in protest songs, in poetry , in folk couplets, on youth T-shirts, on the shelves of revolutionary tourism souvenirs.

Someone thinks and says that any cause is defeated when those who fight for it, that is, those who live for it, perish.

Some say that the harsh Latin American October shattered hope in Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico, throughout Latin America.

Maybe it is. But maybe not.

Maybe those who, like Miguel, took up arms to say “No” were actually saying “Yes” to tomorrow, which then seemed so far away.

Maybe those who, like Miguel, added flame to their word, did it not to set fire to death, but to illuminate life.

Perhaps those who, like Miguel, thought and shot, did so not in order to take their place in the museum of revolutionary nostalgia, but so that peoples, each and every one, would take their true place in the world.

Maybe there will be no name in the calendar that will be tomorrow, or, better yet, there will be a place for each of the names.

Because, perhaps, it is precisely for this reason that the departed, who respond to us with pain every Latin American month, put their crosses on the calendar – the same as this one, who suffers on October 5th.

Maybe because these departed, instead of feeling empty, leave us with a desire to fight for hope, that is, as the Zapatistas say, “to change the world.”

Maybe.

Maybe hope, like our America, is fed from memory.

And maybe memory is nothing more than glue to put together the hope that has been shattered in the calendar that is being forced upon us.

Perhaps this memory that unites us today and brings Latin America back here, side by side, is not a legacy of pain bequeathed to us, but a duty passed on to us.

Maybe.

Perhaps we are here just to find out about this, and even those who are not here are also.

Because maybe today will not be the same as yesterday.

One Chilean revolutionary, one of those who made some people tremble when he took up the guitar, Victor Jara, perhaps thinking about this time that falls on our shoulders today, said and continues to tell us: “How difficult it is to find clarity in the shade, when the sun that illuminates us discolors the truth. And he said and continues to say to us: “To find a way along the way in order to continue the path”[20].

And it was here, on Chilean soil, that a very long time ago Manuel Rodriguez[21] said and continues to say to us, as if pointing the way: “Citizens, we still have a homeland.”

And another, also a Chilean, here, very close, under the bullets that were looking for his heart, found the courage and wisdom to say and continue to tell us: “Not far, but close is the day when the wide road will open again, along which a worthy person will go to build a better society”[22].

Maybe today will not be the same as yesterday.

Perhaps we have already learned these lessons, and soon, in the place where the pages of Latin American history used to be covered with blood, the word will triumph, which will finally be clearly read by those who look from below: “democracy”, “freedom” and “justice” – these full-bodied words with an emphasis on the region of the heart that beats in our common chest.

With all this I want to say that we will win, that we will not be stopped, that the future will be ours, that the wall of chains will be broken, that freedom is the near horizon, but we Zapatistas do not think that this will happen as a result of arcane magic or a declaration written by someone, but because we will continue to work and fight for this.

Brothers and sisters!

And this is what our word wants to tell you:

Fortunately, in this opened vein of Latin America[23] named Chile, the blood is not “ITT”[24], not “Anaconda Cooper”[25], not “ United Fruit”[26], not Ford, not the World Bank, not Pinochet, not those in whose names one or another of them dressed up, but the blood of her workers, her peasants, her students, her Mapuche[27], her women, her youth, her Victor Jara, her Violeta Parra, her Salvador Allende, her Pablo Neruda, her Manuel Rodríguez, her Miguel Enriquez, her memory.

Chilean brothers and sisters!

Receive this greeting from those who admire and love you, the Mexican Zapatistas.

Hello Chile!

From the mountains of southeastern Mexico,

Subcomandante Marcos

Mexico, October 2004

P.S. Forgive me if these words of mine did not become a call for a holiday, like the life and death of someone who today, 30 years later, continues to speak to us. In fact, we only wanted to take advantage of this meeting to modestly and respectfully ask you all to put a red copihue flower on our behalf on the land that preserves it and tell him that here, in the mountains of southeastern Mexico, the name of October is the same – Miguel.

Translation by Oleg Yasinsky

Scientific editing Alexander Tarasov

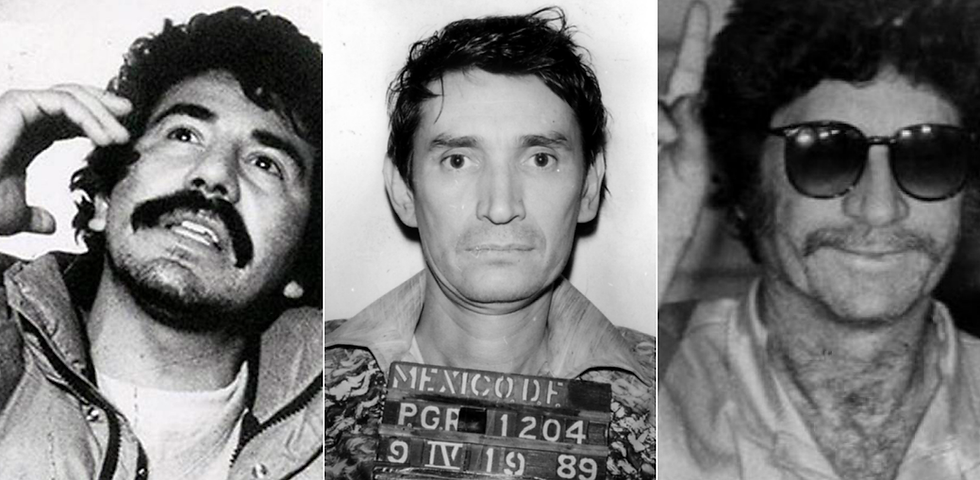

1. Miguel Enrices Espinos (1944-1974)-General Secretary General of the Chilean Left Revolutionary Traffic (Mira), who died on October 5, 1974 1974 1974 1974 unequal battle with the troops of the dictatorship of Pinochet, who cordoned off the house in which he was hiding. The battle of Miguel and his comrades against almost 200 soldiers participating in the special operation lasted more than two hours.

The battle of Miguel and his comrades against almost 200 soldiers participating in the special operation lasted more than two hours.

2. Rio Bravo is the informal (cinematic) name of the Rio Grande del Norte (see footnote 6)

3. Copihue is the symbol of Chile.

4. Aconcagua – the highest mountain in Latin America (6969 m above sea level), located in Argentina near the border with Chile

5. Popocatepetl – a volcano near Mexico City, 5452 m above sea level.

6. Rio Grande del Norte – the river along which the border between the United States and Mexico passes. The common phrase “south of the Rio Grande” means the same as “Latin America”.

7. E. Che Guevara died on October 8, 1967.

8. A reference to the novel by the classic of Mexican literature Mariano Azuela “Those Who Are Below” (1916), dedicated to the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th century.

9. Luis Augusto Turcios Lima (1932-1966) – an outstanding Guatemalan partisan, one of the leaders of the Revolutionary Movement of November 13, died in battle.

10. Marco Antonio Yon Sosa (? -1970) – the legendary Guatemalan guerrilla, the creator of the Revolutionary Movement of November 13. Killed by Mexican military in Chiapas.

11. Roque Dalton Garcia (1935-1975) – an outstanding Salvadoran poet, communist, one of the founders of the partisan Revolutionary Army of the People. He was shot by partisans on charges of treason, fabricated by the partisan commander Joaquin Villalobos (according to one version, an adventurer, according to another, a CIA agent; Villalobos currently works as an adviser to the Colombian army on counterguerrilla warfare).

12. Carlos Fonseca Amador (1936-1976) – one of the founders and leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua, who committed suicide at 1979 with the dictatorship of the Somoza dynasty. In 1976, his group was ambushed by government troops. He was captured alive, executed, and his severed head and hands were delivered to the capital at the personal request of the dictator Anastasio Somoza.

13. Camilo Torres Restepo (1929-1966) – an outstanding Colombian sociologist, theorist of “liberation theology”, a priest who joined a partisan detachment and died in his first battle. Victor Jara dedicated a poignant song to him, ending with the words “Camilo Torres died for life.”

14. Carlos Lamarca (1937-1971) – former junior officer of the Brazilian army, who created the guerrilla movement People’s Revolutionary Vanguard. In an unequal battle with regular troops, he was wounded, then executed.

15. Joao Carlos Marigella (1911-1969) – an outstanding public figure in Brazil, a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Brazilian Communist Party, who led the Action for National Liberation (ALN) – an organization of urban guerrillas that embarked on the path of armed struggle after the overthrow of the democratic government in a coup d’état Joao Goulart. Author of the famous mini-textbook of urban guerrilla warfare. He died in a police ambush.

16. Inti and Coco Peredo – Guido Alvaro “Inti” Peredo Leige (1937-1969) – Bolivian revolutionary, Che’s closest associate in his Bolivian epic, who tried to continue this project after his death. In one of the houses of La Paz, he fought against 150 policemen, was seriously wounded, captured and died from torture. Roberto “Coco” Peredo Leige (1938-1967) – Inti’s brother, an active member of the Che partisan detachment, died in battle a month before his commander.

Inti and Coco Peredo – Guido Alvaro “Inti” Peredo Leige (1937-1969) – Bolivian revolutionary, Che’s closest associate in his Bolivian epic, who tried to continue this project after his death. In one of the houses of La Paz, he fought against 150 policemen, was seriously wounded, captured and died from torture. Roberto “Coco” Peredo Leige (1938-1967) – Inti’s brother, an active member of the Che partisan detachment, died in battle a month before his commander.

17. Raul Sendik (1926-1989) is an outstanding Uruguayan revolutionary thinker and partisan, leader of the National Liberation Movement. Tupac Amaru (“Tupamaros”) – the world’s first organization of urban guerrillas. Spent almost 13 years in solitary confinement in one of the worst prisons in Uruguay, died from the effects of torture three years after his release.

18. Roberto Santucho (1936-1976) – the famous Argentine partisan, leader of the Guevarist Revolutionary Army of the People, which led the armed resistance to the military dictatorship. Died in an unequal battle with the army at 1976 year.

Died in an unequal battle with the army at 1976 year.

19. Cesar Yáñez (?-1974) – creator of the guerrilla center in Chiapas, first called the National Liberation Front and eventually turned into the Zapatista National Liberation Army. Founder of the military-political organization of the Zapatistas. Arrested by Mexican government security agents and considered “missing” ever since.

20. “How difficult it is to find clarity in the shadows, when the sun that illuminates us discolors the truth”, “To find a way on the way to continue the path” – words from Victor Jara’s song “On the Road” (“Caminando, caminando”).

21. Manuel Rodriguez Erdoisa (1785-1818) – Chilean partisan, hero of the struggle for independence from Spain. He was captured and shot. During the dictatorship of Pinochet in Chile, the Patriotic Front. Manuel Rodriguez, who led the armed struggle against the regime.

22. From Salvador Allende’s last radio address to the people of Chile from the encircled presidential palace “La Moneda” on September 11, 1973, a few hours before his tragic death.

han establecido para su personal provecho.

han establecido para su personal provecho.