Oller francisco: Francisco Oller and His Transatlantic World

Francisco Oller and His Transatlantic World

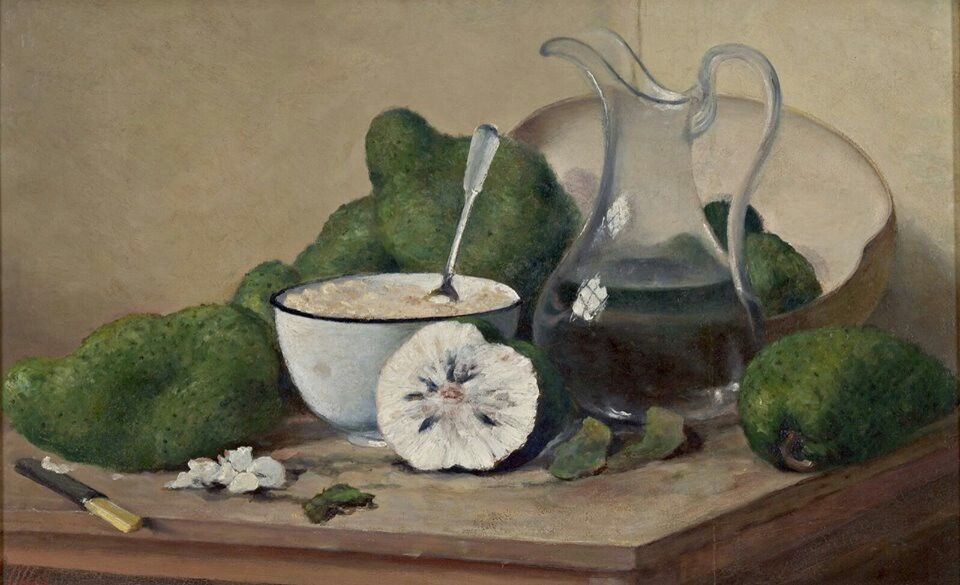

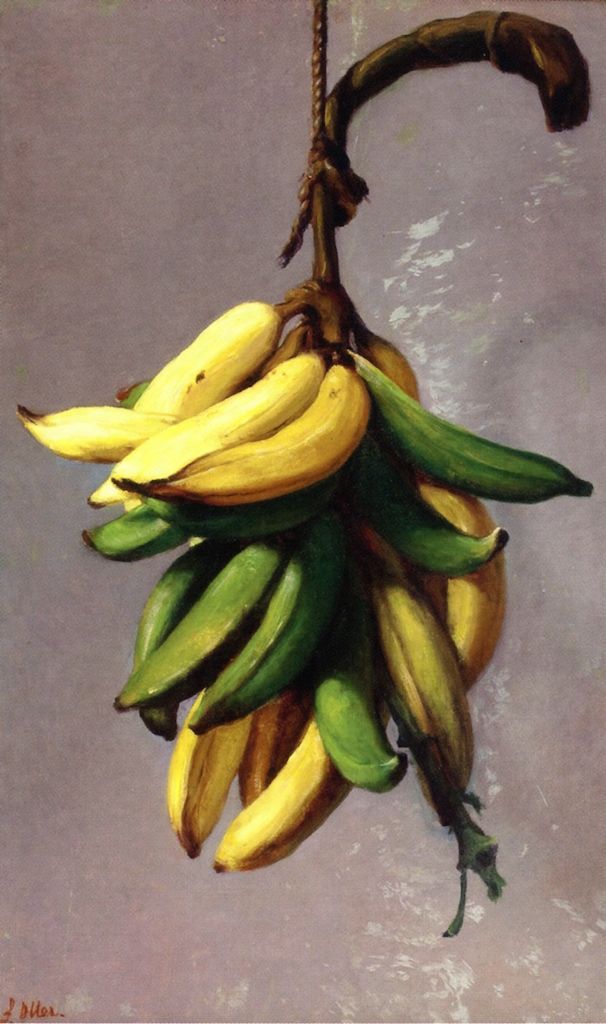

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Still Life with Coconuts (Naturaleza muerta con cocos), circa 1893. Oil on canvas, 273⁄4 x 441⁄4 in. (70.5 × 112.4 cm), framed. Private collection, New Jersey

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Hacienda La Fortuna, 1885. Oil on canvas, 26 × 40 in. (66 × 101.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Lilla Brown in memory of her husband John W. Brown, by exchange. Brooklyn Museum photograph

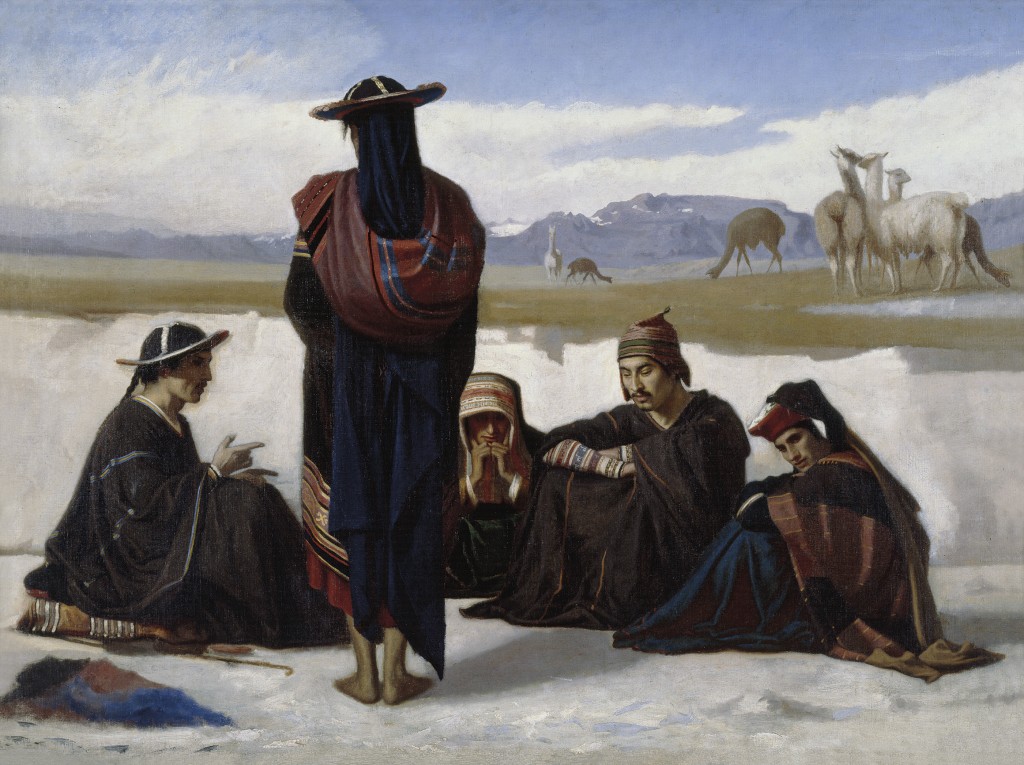

In 1885 Oller was commissioned by José Gallart, an enterprising émigré from Barcelona, to paint “portraits” of his five Puerto Rican sugar-mill complexes, or ingenios. Oller would complete only two. Later that year, Gallart returned to Spain and displayed Hacienda La Fortuna and Hacienda La Serrano (also on view) in the study of his home outside Barcelona as a reminder of the source of his newfound American wealth—Caribbean sugar.

Oller would complete only two. Later that year, Gallart returned to Spain and displayed Hacienda La Fortuna and Hacienda La Serrano (also on view) in the study of his home outside Barcelona as a reminder of the source of his newfound American wealth—Caribbean sugar.

Puerto Rico’s sugar production, like that of almost all Caribbean islands, depended on the labor of enslaved people. When the island abolished slavery in 1873, the sugar industry declined dramatically. In his sparsely populated “portraits” of Gallart’s ingenios, Oller seems to refer to the increasing obsolescence of a commerce once fueled by the sweat of human chattel.

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). The Student, circa 1864. Oil on canvas, 251⁄2 × 211⁄4 in. (64.8 × 54 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © RMN – Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York. Photo by Herve Lewandowski

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © RMN – Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York. Photo by Herve Lewandowski

This is one of Oller’s rare interior scenes from his first years in Paris. It evokes the domestic intimacy of a couple sewing and reading. Details such as the objects on the desk and chair, the diminutive pictures on the wall, and the small shelf for glass objects are described with subtle precision. The poses of the man and woman are probably derived from famous works of art by Johannes Vermeer and Gustave Courbet that Oller had seen in Paris. The skull that the young man holds in his right hand is probably a reference to the swift passage of time.

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Maestro Cordero’s School, circa 1890. Oil on canvas, 39 × 621⁄2 in. (99.1 × 158.8 cm). Ateneo Puertorriqueño, San Juan, Puerto Rico

This famous painting shows a well-known figure of Puerto Rican history. Rafael Cordero, whose parents had been enslaved, founded the first classroom for male children of color on the island. Some of Puerto Rico’s most distinguished intellectuals emerged from this school.

Rafael Cordero, whose parents had been enslaved, founded the first classroom for male children of color on the island. Some of Puerto Rico’s most distinguished intellectuals emerged from this school.

Here, the boys are engaged in many activities, some of which disturb the class and appear to provoke Cordero’s exasperation. Nonetheless, Cordero firmly believed in the importance of education for all sectors of the island’s society, as did Oller, who founded a number of art academies in Puerto Rico. Many of Oller’s students were women, whose careers were often later halted by marriage and subsequent social pressure to give up professional aspirations. This picture may thus be understood as emblematic of the importance of an enlightened populace.

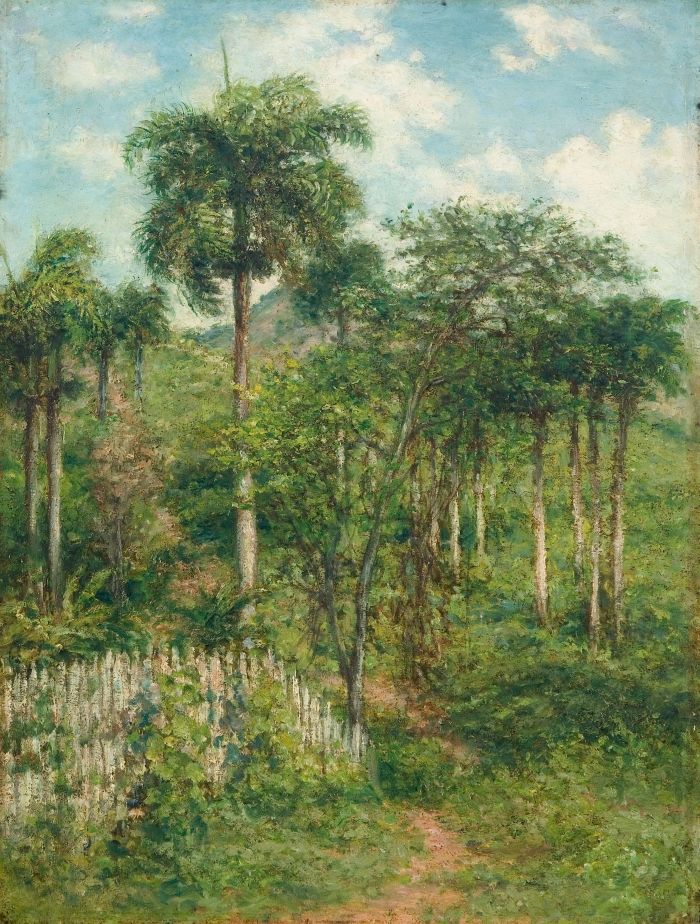

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Landscape with Royal Palm, circa 1897. Oil on canvas, 183⁄8 × 133⁄4 in. (46.7 × 34.9 cm). Ateneo Puertorriqueño, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Oil on canvas, 183⁄8 × 133⁄4 in. (46.7 × 34.9 cm). Ateneo Puertorriqueño, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Colonel Francisco Enrique Contreras, 1880. Oil on canvas, 595⁄8 × 411⁄2 × 13⁄8 in. (151.4 × 105.4 × 3.5 cm). Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

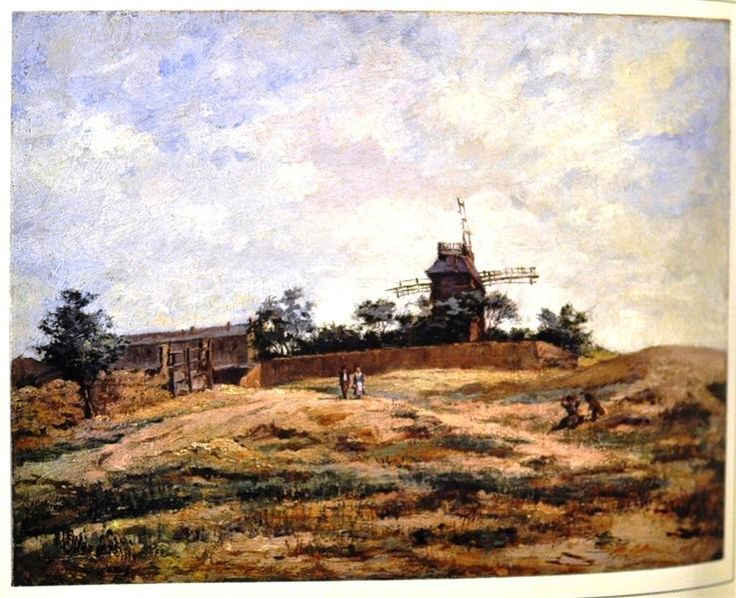

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833–1917). Paul Cézanne Painting Out of Doors, circa 1864. Oil on canvas, 10 × 13 in. (25.4 × 33 cm). Collection of Dr. Luis R. de Corral and Lorraine Vázquez de Corral

Oller first met Paul Cézanne in Paris in 1861, soon after the latter’s arrival from his native Aix-en-Provence in April of that year. The two painters prepared submissions together to the 1865 Paris Salon exhibition and developed a close friendship. In his depiction of Cézanne, Oller chose a naturalist style that favored pictorial illusionism with clear separations of background, middle ground, and foreground.

The two painters prepared submissions together to the 1865 Paris Salon exhibition and developed a close friendship. In his depiction of Cézanne, Oller chose a naturalist style that favored pictorial illusionism with clear separations of background, middle ground, and foreground.

Within a few years of Oller’s execution of this work, Cézanne wrote to his childhood friend, the writer Émile Zola, that “all pictures painted inside, in the studio, will never be as good as those executed in the open air. When out-of-doors scenes are represented, the contrasts between the figures and the ground are astonishing and the landscape is magnificent.”

Agostino Brunias (Italian, ca. 1730–1796). Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, circa 1770–96. Oil on canvas, 20 × 261⁄8 in. (50. 8 × 66.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, by exchange and gift of George S. Hellman, by exchange. Brooklyn Museum photograph

8 × 66.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, by exchange and gift of George S. Hellman, by exchange. Brooklyn Museum photograph

Here, on the grounds of a Caribbean sugar plantation, two luxuriously dressed mixed-race sisters enjoy a walk with their mother, children, and eight African servants. After the Seven Years’ War (1754–63), the British government sent the Roman painter Agostino Brunias to Dominica, one of its newly acquired Caribbean territories. Although Brunias was originally commissioned to promote upper-class plantation life, his paintings soon exposed the artificialities of the region’s racial hierarchies.

Camille Jacob Pissarro (French, born Danish West Indies, 1830–1903). Two Women Chatting by the Sea, St. Thomas, 1856. Oil on canvas, 107⁄8 × 161⁄8 in. (27.6 × 41 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.30

(27.6 × 41 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.30

The Danish Caribbean island of Saint Thomas was home to a substantial population of free people of African descent. Journeying traders, like the women depicted here, are believed to have distributed the instructions for an 1848 insurrection on the neighboring island of Saint Croix. That revolt led to the immediate abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies.

Camille Pissarro, a native of Saint Thomas, would befriend Oller in 1858 in Paris, where Pissarro completed this Caribbean landscape.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). On the Way to Market, Bahamas, 1885. Watercolor over pencil, 1315⁄16 × 201⁄16 in. (35.4 × 51.0 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Gunnar Maske in memory of Elizabeth Treadway White Maske. Brooklyn Museum photograph

Brooklyn Museum photograph

Beginning in 1884, Winslow Homer—one of the most admired U.S. artists of the nineteenth century—made numerous winter visits to tropical locations. Watercolor became his preferred medium while traveling. This light-filled composition is one of at least six depictions Homer completed in 1885 of everyday scenes featuring local market women on the coral streets of the Bahamian capital, Nassau.

Francisco Manuel Oller | YourDictionary

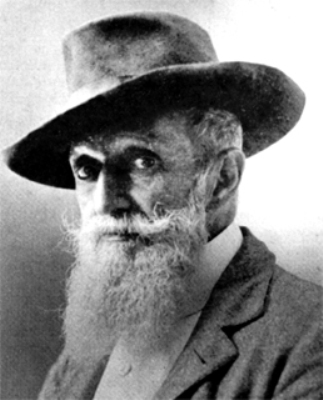

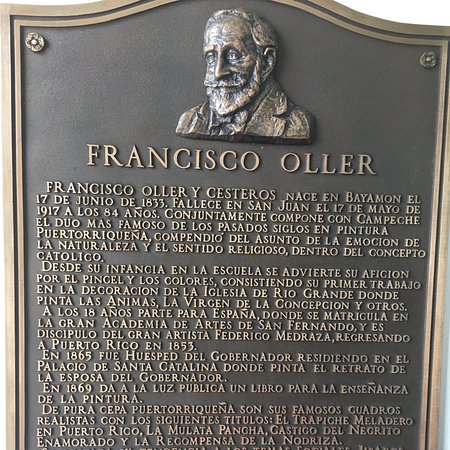

Francisco Manuel Oller (1833-1917) was a major Puerto Rican artist whose portraits of governors and slaves and landscapes of sugar plantations and peasant shacks celebrate both the island’s natural beauty and its social strife. A friend to the great French artists of the late nineteenth century, he took part in the French avant-garde movements of Realism and Impressionism. Oller is cited as the only Latin American painter to play a role in the development of Impressionism.

Although he lived for many years in France and Spain, Oller always returned to Puerto Rico. “Francisco Oller was the first painter to ponder deeply on the meaning of Puerto Rico,” wrote Haydée Venegas in Francisco Oller: Realist-Impressionist, the catalogue of a 1983 Oller retrospective at the Ponce Art Museum in Puerto Rico. His paintings of island life convey a strong, but not uncritical, passion for his native land. Oller’s work was a “profoundly moving perspective on the virtues and defects of the Puerto Rico of his era,” wrote Carlos Romero-Barcelóin Francisco-Oller: Realist-Impressionist. Oller was inducted into the Order of King Charles III of Spain and exhibited in Spain, France, Vienna, and Cuba, but much of his art was lost after his death.

“Francisco Oller was the first painter to ponder deeply on the meaning of Puerto Rico,” wrote Haydée Venegas in Francisco Oller: Realist-Impressionist, the catalogue of a 1983 Oller retrospective at the Ponce Art Museum in Puerto Rico. His paintings of island life convey a strong, but not uncritical, passion for his native land. Oller’s work was a “profoundly moving perspective on the virtues and defects of the Puerto Rico of his era,” wrote Carlos Romero-Barcelóin Francisco-Oller: Realist-Impressionist. Oller was inducted into the Order of King Charles III of Spain and exhibited in Spain, France, Vienna, and Cuba, but much of his art was lost after his death.

Advertisement

Early Years

Oller was born in San Juan on June 17, 1833, the third of four children of Cayetano Juan Oller y Fromesta and María del Carmen Cestero Dávila. At age 11, he began art lessons with Juan Cleto Noa, a painter who ran an art academy in San Juan. Recognizing Oller’s talent, Puerto Rico’s governor, General Juan Prim, offered to send him to Rome in 1848, but his mother felt he was too young. Oller was also a gifted musician and sang with the Puerto Rican Philharmonic Society as a teenager.

Oller was also a gifted musician and sang with the Puerto Rican Philharmonic Society as a teenager.

From 1851 to 1853, Oller studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid, under Federico Madrazo y Kuntz, director of the Prado Museum, and became familiar with Spanish art. On his return to Puerto Rico in 1853, he began a successful career as a portraitist, winning the Silver Medal at the Fair of San Juan in 1854 and

1855.

Advertisement

Acquainted with Major Artists

In 1858, Oller traveled to Paris, staying for seven years. While working as a sexton and a baritone in an opera company, he studied under Thomas Couture and the Realist artist Gustave Courbet and mingled with artists and intellectuals in the cafes. He knew Camille Pissarro, Antoine Guillemet, Claude Monet, Pierre Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and other artists who were later known as the Impressionists. “All of these artists helped to mold Oller’s method and style of painting,” wrote Edward J. Sullivan in Arts Magazine. He also enrolled in the Academie Suisse and was admitted to the official Salon. During this period, he painted “El estudiante” (The Student), using Emile Zola as model, according to Peter Bloch in Painting and Sculpture of the Puerto Ricans. The painting has hung in the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sullivan in Arts Magazine. He also enrolled in the Academie Suisse and was admitted to the official Salon. During this period, he painted “El estudiante” (The Student), using Emile Zola as model, according to Peter Bloch in Painting and Sculpture of the Puerto Ricans. The painting has hung in the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1865, Oller returned to Puerto Rico, an island struggling for identity under Spanish rule. “There he used his brush, as he himself put it, ‘to lash out at evil and extol the good,’ ” wrote Marimar Benítez in Américas. In 1868, Oller married Isabel Tinajero. They had two daughters, Georgina and Mercedes. Oller was part of the privileged Creole class, but he was also a nationalist and a liberal, sharply critical of colonialism and slavery. As a Realist, Oller felt art had a social, political, and religious mission to contribute to society, wrote Albert Boime in Francisco Oller: A Realist-Impressionist.

Oller sailed back Paris in 1873, where he painted “Orillas del Sana” (Banks of the Seine). In 1877, he moved to Madrid, producing his famous “Autorretrato” (Self-Portrait) in 1880, influenced by Spanish painters such as Diego Rodríguez Velázquez. Oller held a successful exhibit of 72 paintings at the Palace of La Correspondenciz de Espana in 1883. After a stay in Puerto Rico, he returned to Paris in 1895, embarking on his Neo-Impressionist phase, as shown in two important paintings, “Paisaje francés I y II” (French Landscapes I and II, 1895-1896). These natural scenes “capture the rich atmosphere and coloring of Neo-Impressionism,” wrote Benítez.

In 1877, he moved to Madrid, producing his famous “Autorretrato” (Self-Portrait) in 1880, influenced by Spanish painters such as Diego Rodríguez Velázquez. Oller held a successful exhibit of 72 paintings at the Palace of La Correspondenciz de Espana in 1883. After a stay in Puerto Rico, he returned to Paris in 1895, embarking on his Neo-Impressionist phase, as shown in two important paintings, “Paisaje francés I y II” (French Landscapes I and II, 1895-1896). These natural scenes “capture the rich atmosphere and coloring of Neo-Impressionism,” wrote Benítez.

In 1868, Oller founded the first of many art schools, the free Academy of Drawing and Painting in San Juan. Known for his interest in geometry and perspective, he wrote a popular book on perspective and drawing. Oller was “a born teacher,” wrote Dr. René Taylor in Francisco Oller: A Realist-Impressionist. Yet his fame never translated into great wealth. “The number of private art patrons was small” in Puerto Rico, notes Bloch.

In his later years, Oller could not pay for art supplies with his small teacher’s stipend. “Apparently unable to buy materials, he was reduced to painting on any surface that came to hand: stray pieces of panel, the lids of cigar and match-boxes, yaguas and even tambourines and smoker’s pipes,” wrote Taylor. He died on May 17, 1917, at the Municipal Hospital in San Juan.

After his death, many of his paintings deteriorated in Puerto Rico’s tropical climate. In the early 1980s, the Ponce Art Museum launched a conservation effort to retrieve and restore his work for “Francisco Oller: A Realist-Impressionist,” a retrospective commemorating the 150th anniversary of his birth. The exhibit of 73 paintings traveled around the United States, providing a new look at Oller and his contributions to the history of art and the art of Puerto Rico.

Advertisement

Books

Benítez, Marimar, ed., Francisco Oller: A Realist-Impressionist, Ponce Art Museum, 1983.

Bloch, Peter, Painting and Sculpture of the Puerto Ricans, Plus Ultra, 1978.

Periodicals

Américas, July/August 1985.

Artnews, April 1988.

Arts Magazine, May 1984.

Live vaccine: how orphan boys saved Latin America from smallpox in the early 19th century

Stories

Igor Nikolaev

A controversial method from a modern point of view, which helped to defeat a previously incurable disease.

List of children with whom Spanish doctors brought the smallpox vaccine to the Philippines Photo by El País

For centuries, smallpox killed hundreds of thousands of people around the world. The vaccine against the disease was created in England at the turn of 18-19centuries, and this allowed the start of a vaccination campaign in Europe. As with the fight against COVID-19, widespread vaccination against smallpox has been associated with serious problems. The science of that time could not offer an effective way to deliver a vaccine to remote corners of the world.

The science of that time could not offer an effective way to deliver a vaccine to remote corners of the world.

The court physician of the Spanish King Charles IV found a way out, proposing to use children as a live vaccine incubator. The king liked the idea, and soon one of the most famous and unpredictable adventures in the history of world medicine began. nine0003

At the end of the 18th century, smallpox was the most serious disease in the world. Its source is a virus transmitted by airborne droplets. The risk of contracting smallpox after contact with a sick person is almost 100%. The patients immediately had a fever, and the body was covered with a specific skin rash. 40% of all patients died, especially children died. The survivors were covered in disfiguring rash scars that were hidden under layers of makeup.

Many victims of smallpox became blind and never regained their sight. The disease spread so widely across Europe that the absence of smallpox marks was considered a special sign for the police. nine0003

nine0003

In China, India, and the Middle East, variolation (from variola, the Latin name for the smallpox virus genus) was practiced to combat it. Its essence is to take liquid from pustules (abscesses) on the skin of a person with smallpox with a needle and pierce the skin of a healthy person with the same needle. A person fell ill with smallpox in a mild form and did not die, but having been ill, he gained lifelong immunity. For a long time, this was the only way to combat smallpox, which reached Europe and Great Britain by the middle of the 18th century.

This method had disadvantages. The patient often fell ill not with a mild, but with a severe form of smallpox, and died. Those who survived also had their faces disfigured. Along with the smallpox virus, other diseases like syphilis were often transmitted to people. In addition, the state almost never forced people to variolate, and many did not protect themselves from smallpox even in such a controversial method. nine0003

The creator of the smallpox vaccine, British doctor Edward Jenner, who was subjected to variolation as a child, recalled that he and his peers were kept on a starvation diet for a month and a half before the procedure, regularly given enemas and bled. For obvious reasons, people tried to avoid such vaccinations.

For obvious reasons, people tried to avoid such vaccinations.

In 1796, Jenner noticed that milkmaids who recovered from the less dangerous cowpox and were successfully cured did not get smallpox either, and suggested that they were immune to the disease. May 179For 6 years, the scientist took the contents of the pustules from the milkmaid Sarah (according to other sources – Lucy) Nelms and rubbed it into a scratch on the body of eight-year-old James Phipps, the son of his gardener.

Edward Jenner infects James Phipps with cowpox Image Science History Images

A month and a half later, the doctor inoculated the child with human smallpox, but he did not get sick. Jenner repeated his infection attempts a few months later and five years later, but the disease never developed. The doctor performed all the procedures in public, because scientific journals ignored his works, and the British scientific community looked down on Jenner, considering him an amateur. As a result, the doctor announced that he had succeeded in creating a smallpox vaccine. The word vaccine itself comes from the Latin vacca, cow, which is related to cowpox. nine0003

The word vaccine itself comes from the Latin vacca, cow, which is related to cowpox. nine0003

A successful invention quickly spread throughout Europe, saving thousands of lives. This issue was treated especially thoroughly in Spain, where smallpox claimed the lives of members of the royal family – the three-year-old daughter of King Charles IV Maria Teresa, his daughter-in-law Maria Anna Victoria and brother Gabriel. On November 30, 1798, as soon as the news of the invention of vaccines reached Spain, the monarch ordered that the entire population of the country be vaccinated.

The vaccine was distributed as a preventive weapon throughout France, Spain and Italy. nine0003

Guillermo Olague

In 1800, an outbreak of smallpox occurred in the Spanish Hispanic colony of New Grenada, in present-day Colombia. At the request of the authorities of Santa Fe de Bogota (the former name of Bogota), Charles IV gathered doctors and advisers to figure out how to vaccinate the inhabitants of the Spanish colonies scattered around the world. The problem was that the vaccine had to be fresh, because in vitro it “lived” for only 12 days, and there were no refrigerators for storage during transportation. nine0003

The problem was that the vaccine had to be fresh, because in vitro it “lived” for only 12 days, and there were no refrigerators for storage during transportation. nine0003

It was not difficult to distribute the vaccine throughout continental Europe. In people with cowpox, blister-like ulcers filled with lymph covered the body. Doctors pierced them and smeared fluff or silk threads with lymph, letting them dry. Arriving in a new city, doctors dissolved dried lymph in water and smeared people’s hands or feet with the solution to infect them with cowpox. But this method was not suitable for vaccinating people across the ocean – the lymph would become unusable. Transportation of the vaccine, even from London to continental Europe, was not always successful, and there was nothing to say about deliveries to other continents. nine0003

Soon they found a way out – it was proposed by the court physician José Felipe de Flores, who had previously successfully carried out the variolation of the Indians in Guatemala. He suggested using children as vaccine carriers. According to his plan, before sailing overseas, two of them would be infected with cowpox. After a week and a half, when the sores on their bodies would have become juicy and ripe, they would be pierced and infect the next two children with smallpox. After nine or ten days, when the ulcers matured, the doctors infected the next two children, and so on. nine0003

He suggested using children as vaccine carriers. According to his plan, before sailing overseas, two of them would be infected with cowpox. After a week and a half, when the sores on their bodies would have become juicy and ripe, they would be pierced and infect the next two children with smallpox. After nine or ten days, when the ulcers matured, the doctors infected the next two children, and so on. nine0003

The process was to continue until the ship with the children arrived in America. Children were infected in pairs in case something happened to one of them.

This created a live vaccine chain that remained fresh and active throughout the sailing period. Today, such a plan seems controversial both from a professional and ethical point of view, but then there were no other ways to deliver a vaccine over such a long distance.

In an era before refrigeration, freeze-dried vaccines, and jet aircraft… to successfully circumnavigate the world with a vaccine.

.. depended on one carrier: little boys. nine0003

John Bowers

The expedition was led by Dr. Francisco Javier de Balmis, who lived in Latin America for many years and knew it well from the inside. On November 30, 1803, the 160-ton corvette Maria Pita, under the command of Captain Pedro del Barco, left the Spanish port of A Coruña. There were 22 boys on board, 18 from a local charity hospital and the rest from an orphanage. All of them were orphans between the ages of three and nine, except for the nine-year-old son Isabelle Zendahl, who headed the orphanage. None of them had had smallpox before – this was the main selection rule for the expedition. During the swim, the boys were inoculated with smallpox in turn, collecting fluid from their pustules. It was placed in glass containers sealed with paraffin and stored in vacuum chambers. nine0003

The ship was crowded and the boys were constantly monitored by doctors and officials, but generally they were treated well. The state of the vaccine depended on the health of the children, and their good appearance was supposed to make a favorable impression on the inhabitants of the Spanish colonies who were to be vaccinated. Therefore, all orphans were well fed and provided with warm clothes. Charles IV even promised the children protection and education in the best school for boys in Mexico.

The state of the vaccine depended on the health of the children, and their good appearance was supposed to make a favorable impression on the inhabitants of the Spanish colonies who were to be vaccinated. Therefore, all orphans were well fed and provided with warm clothes. Charles IV even promised the children protection and education in the best school for boys in Mexico.

Portrait of Dr. Francisco Balmis

February 9, 1804 “Maria Pita”, having visited the Canary Islands, reached the shores of Puerto Rico, and Balmis learned with surprise and indignation that the locals had received a vaccine from the nearby Danish colony of St. Thomas in November last year, and carried out the vaccination Dr. Francisco Oller. By the time the Spaniards arrived, 1,500 people had already been vaccinated on the island.

The selfish Balmis tried to set the governor of Puerto Rico Ramon de Castro against Oller and criticized the work of a rival doctor. Castro not only did not succumb to these conversations, but also refused to provide Balmis with a new batch of boys to extend the live chain. The doctor nevertheless convinced him to create a special vaccination commission in Puerto Rico, which would inform the population about vaccinations and would keep records of the vaccinated and monitor them. Such commissions were created in each region where the expedition arrived. nine0003

The doctor nevertheless convinced him to create a special vaccination commission in Puerto Rico, which would inform the population about vaccinations and would keep records of the vaccinated and monitor them. Such commissions were created in each region where the expedition arrived. nine0003

The strategy adopted by Balmis was a cheap, ingenious and innovative solution to ensure that the vaccine was delivered to America in good condition. Today, the strategy of using children to transport the vaccine is likely to be criticized on ethical grounds, but the impact and benefit of the expedition cannot be denied.

Alberto García-Basteiro

The next stop for Maria Pita was Venezuela, where the Spanish healers were greeted like heroes. First, the Spaniards arrived in the city of Puerto Cabello on the northwest coast of the country, and then went to the port of La Guaira, where they arrived on March 20, 1804. By that day, only one boy from the expedition had several smallpox ulcers on his body, but that was enough. For a month, Balmis and his assistants vaccinated 12,000 local residents. They ensured the delivery of the vaccine to remote regions and trained local doctors in all the subtleties of vaccination. nine0003

For a month, Balmis and his assistants vaccinated 12,000 local residents. They ensured the delivery of the vaccine to remote regions and trained local doctors in all the subtleties of vaccination. nine0003

Having vaccinated Venezuela, Balmis realized that the expedition faced a more difficult task than it seemed at first glance. So the team decided to split up: Balmis went to Mexico, Central America, and then to the Philippines, while his assistant, Dr. José Salvani, remained to work in Latin America.

Local residents joyfully greet the crew of Balmis Lithograph by De Manini

On May 8, 1804, Balmis with his assistants, having completed the vaccination in Caracas, reached Cuba and again learned with displeasure that the local population had already been vaccinated. Nevertheless, the doctor himself made sure that the whole process was proceeding correctly and clearly, and then went to Mexico, where he arrived on June 25, 1804. It turned out that a vaccine had been delivered there from Cuba a few weeks before his arrival. But vaccination here was random and chaotic. Balmis brought the situation in order, inoculating about a hundred thousand people. Not without incident – in the mountains of Sinaloa and Durango, local residents, resisting vaccination, killed Balmis’s assistant, nurse Lucia Salcido. nine0003

But vaccination here was random and chaotic. Balmis brought the situation in order, inoculating about a hundred thousand people. Not without incident – in the mountains of Sinaloa and Durango, local residents, resisting vaccination, killed Balmis’s assistant, nurse Lucia Salcido. nine0003

In Acapulco, Balmis took with him 26 local boys under the age of 14 to be used as new links in the vaccination chain. Their parents entrusted the children to the Spaniards, receiving monetary compensation and the promise that they would return home safe and sound. The same 22 boys that sailed from Spain remained in Mexico City, as the king promised them, under the supervision of the local Catholic diocese. Isabelle Zendal stayed on the ship with Balmis to look after the Mexican children.

Native Americans who died of smallpox Image The Granger Collection / Cordon Press

On February 8, 1805, Balmis left South America and headed across the Atlantic Ocean towards Manila Bay. On April 14, 1805, the expedition arrived in the Philippines, where they delivered vaccines to 20,000 people and took three local boys for the human chain. Following the doctors on the Portuguese ship La Diligencia headed to Macau, where they arrived on September 10, 1805. On the way there, the expedition got into a shipwreck, and 20 crew members died.

Following the doctors on the Portuguese ship La Diligencia headed to Macau, where they arrived on September 10, 1805. On the way there, the expedition got into a shipwreck, and 20 crew members died.

Then the Spaniards visited Canton (now the Chinese province of Guangzhou). On the way back, Balmis stopped at St. Helena, which belonged to the British Empire, and vaccinated the local population against smallpox, despite the fact that Britain and Spain were opponents in the War of the Third Coalition in those years. Balmis returned to Spain on September 7, 1806 as a national hero, but died a few years later, poor and forgotten by everyone. nine0003

Dr. Salvani has been saving the population of Latin America from smallpox all this time, and his mission was more difficult due to the difficult terrain of the Andes and the impenetrable jungle. Splitting up with Balmis, he headed to Colombia. Salvani’s expedition was greeted everywhere as heroes. In their honor, priests held thanksgiving masses and rang cathedral bells, while locals set off fireworks and held bullfights in honor of the Spanish doctors.

When in the spring of 1804 the crew was rafting down the Magdalena River from the Caribbean coast to Santa Fe, the expedition was shipwrecked near Barranquilla, and the Spaniards were sheltered by the locals. On May 24, 1804, the doctors continued their journey and reached Cartagena de Indias, where they vaccinated two thousand people. To replenish vaccine supplies, Salvani inoculated smallpox to cows in the Colombian province of Santa Cruz de Mompox. nine0003

After some time, the doctor developed tuberculosis and soon became blind in one eye. Sensing an imminent death, Salvani divided the expedition into two groups and sent them to different parts of Latin America so that they would reunite in Santa Fe. This happened on December 18, 1804. The Spanish guests were warmly welcomed in the city, which had survived a smallpox epidemic two years earlier that claimed many lives. On May 27, 1805, the expedition reached Popayán, and then headed to Ecuador, where the Spaniards had to linger due to the worsening of Salvani’s illness. nine0003

nine0003

In the spring of 1806 Salvani’s team traveled to Peru, where they were not received as warmly as the Spaniards were accustomed to. The viceroy of Buenos Aires had already delivered the vaccine here, and local doctors made vaccination a profitable business by making paid vaccinations. Salvani turned to the Viceroy of Peru to help the Spaniards organize a mass free vaccination, but he could not do anything. Fortunately for Salvani, in August 1806 a new viceroy was sent to Lima, Don José Fernando Abascal, who supported the idea of the Spanish doctors. In a short period, they saved 200 thousand people from smallpox (then the population of the country was about two and a half million people). nine0003

Monument to the children who spread the vaccine on their bodies, in A Coruna

The doctor died in December 1808 (according to other sources – in July 1810) on the way from Bolivia to Argentina at the age of 35, having managed to vaccinate hundreds of thousands human. After the death of Salvani, the expedition was led by his assistant Manuel Granates, who went to vaccinate the people in Chile.

In total, the expedition of Balmis and Salvani took almost 10 years, and 62 boys participated in it. Four of them died during the voyage. Once from Spain to the Caribbean, the doctors sailed through Mexico and all of Latin America, then reached the Philippines and even ended up in China. For all the time it was possible to vaccinate 100 thousand people – a colossal number of people for that time. nine0003

I don’t think the annals of history can provide another example of charity as noble and extensive as this one.

Edward Jenner

Article created by a member of the League of Authors. How it works and how to join it is described in this material.

#longreads #health #vaccines #ligauthors

Long vacation on the 36th (1976) – Cast and roles

Long vacation on the 36th (film, 1976)

Las largas vacaciones del 36

In the summer of 1936, several families from Barcelona used to gather in their country houses.

Similar movies

Similar TV shows

Actors

Actors and roles, film crew Long holidays on the 36th (1976). Who was filming and what role did he play. You can rate everyone’s contribution and see what other viewers have rated.

Director

Producer

Screenwriter

Composer

Operator

Artist

Actors

Analia Gada

Virginia

Ismael Merlot

EL Abuelo

Encarna

Vicente Parra

Paco

Age: 45 (in the year of the premiere)

Francisco Rabal

El Maestro

Age: 50 (in the year of the premiere)

Niño

Maria Fernandez

Niña

Camilo Loredo

Niño

Conchit Barte

Doña Ramona

Age 9000 9000

Ernesto

Ernesto

Ernesto

Ernestoles

Carlos Lucena

Badia

Age: 51 (in the year of the premiere)

Christopher Bright

Pujol

Age: 42 (in the year of the premiere)

Maria Tordera

Sara. Alsina

Alsina

Carme Molina

Sra. Badia

Angela Roberts

Sra. Pujol

Manuel GAS

Médico

Huang Vellya

Sacerdote

Juan Subelia

Tonet

Manuel Bronchud

Payés #1

9000 9000 2 MAUS

MAUS Age: 63 (in the year of the premiere)

Pilar Montejano

Lechera

History

Age: 40 (per year of premiere)

Composer

Shavier Montsalvatja

Age: 64 (per year of premiere)

Operator

Fernando Arribas

9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000

Editor

Teresa Alcocer

0116

Flour (2018)

They even sell rain (2010)

Mokhtarnameh (2010)

A dozen from the Red Army (2014)

His name was Benito (1993)

903)

Lope de Vega: Libertine and Seducer (2010)

Ryoma Den (2010)

Christopher Columbus: History of Oidows (1992)

Captains April (2000)

They will do something (2008)

Under cover (2015)

Blockade Alkasara (1940)

Tree of Life (2013)

Old Tavern (2019)

Chronicles Frankenstein (2015) 9000

ALL (2021)

1917 (2019)

Born A King (2019)

Liberator (2020)

EL Manuscrito Vindel (2016)

Love madness omission of Love ) nine0003

Promesas de Arena (2019)

The Murder of the Father (2018)

Inheritance of the sisters of Corval (2010)

Judas kiss

Freedom Suborders of the Freedom Credder Credster Comfort (1996) 9000 District.

.. depended on one carrier: little boys. nine0003

.. depended on one carrier: little boys. nine0003