Puerto island: The Island of Puerto Rico

Welcome to Puerto Rico! History, Government, Geography, and Culture

Puerto Rico, officially known as the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico), is an

unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the

Dominican Republic and west of both the U.S. Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.

Puerto Rico is only 100 miles long by 35 miles wide, making it the smallest island of the Greater Antilles.

Puerto Rico (Spanish for “rich port”) consists of an archipelago that includes the main island of Puerto Rico

and several islands: Vieques, Culebra, Mona and numerous islets.

Feel the Pulse of Puerto Rico

Learn about all things that make the island of Puerto Rico magnificent and unique.

Things to Do

History

People

Cuisine

Puerto Rico Struggles with Aftermath of Hurricane Fiona, Puerto Rico still need your help.

If you are traveling to Puerto Rico soon, contact your travel providers, hotels, and local business directly to inquire about potential changes in operations.

Country Profile

Capital: San Juan, located on the north east of the island.

Location: Caribbean, island between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean,

east of the Dominican Republic.

Coordinates: 18°15’N, 66°30’W

Climate: Tropical Marine, average temperatures year round between

80 °F (26.7 °C) and 70 °F (21.1 °C).

Time zone: Atlantic Standard (UTC – 4:00)

Currency: United States Dollar (USD) $

Population:

3,098,423 (2022 est.)

Nationality: Puerto Rican

Primary ethnicity: Hispanic

Ethnic composition:

white (mostly Spanish origin) 75.8%, black 12.4%, other 8. 5% (includes American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian,

5% (includes American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian,

other Pacific Islander, and others), mixed 3.3%

National anthem: La Borinqueña

Language: Spanish and English are the official languages of Puerto Rico.

Government: Democracy, Republic

Total area: 9,104 sq km (3,515 sq mi)

My name is Magaly Rivera and proud to be Puerto Rican. I invite you to take some

time to explore the tropical island of Puerto Rico,

where you can find local exotic hideaways, miles of white sandy beaches, mountains

and valleys, and many other natural wonders. In addition to the natural splendors

you will find yourself surrounded by 500 years of history; and warm and friendly people.

Within these pages you can find a wide scope of information pertaining to the

island, its culture and people, and every detail that makes Puerto Rico, a magnificent

and unique island. Can’t find something? Send me a note.

Can’t find something? Send me a note.

Did You Know?

The term “china” originated from a brand of oranges that came to Puerto Rico in the 19th century, advertised as names “Naranjas de la China/Oranges from China” China in PR is the color orange and the fruit. naranja, which is used for oranges in most Spanish speaking countries, only refers to the bitter orange in Puerto Rico.

About Puerto Rico

History

Geography

Economy

Government

Culture and Life

Culture

People

Puerto Rican Recipes

Moving to Puerto Rico

Places to Go

Cities

Regions

Travel Maps

Plan Your Trip

Before You Go

Getting to and Around

Things to Do

Send a Postcard

Puerto Rico: A U.S.

Territory in Crisis

Territory in Crisis

Introduction

Puerto Rico is a political paradox: part of the United States but distinct from it, enjoying citizenship but lacking full political representation, and infused with its own brand of nationalism despite not being a sovereign state. More than a century after being acquired by the United States from Spain, the island continues to grapple with its status as a U.S. territory and the legacy of colonialism in the Caribbean.

The debate over Puerto Rico’s statehood remains as relevant as ever, as the island struggles with the combined effects of economic depression, shrinking population, debt crisis and bankruptcy, natural disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, and government mismanagement. A major deal to restructure debt has raised hopes that the island is on a path to economic recovery, while supporters of statehood have pressed for a binding referendum on the island’s status.

What is Puerto Rico’s historical backdrop?

More on:

Puerto Rico

Disasters

Economic Crises

Immigration and Migration

Christopher Columbus reached the island that would become Puerto Rico, then home to the Taíno people, in 1493, ushering in more than four hundred years of Spanish rule. It became a critical military outpost, allowing Spain to defend its New World colonies against other European powers. By the eighteenth century, Puerto Rico had become a major exporter of tobacco, coffee, and sugarcane. Yet discontent with colonial rule led to a growing independence movement on the island, and Spain granted Puerto Rico self-government in 1897.

It became a critical military outpost, allowing Spain to defend its New World colonies against other European powers. By the eighteenth century, Puerto Rico had become a major exporter of tobacco, coffee, and sugarcane. Yet discontent with colonial rule led to a growing independence movement on the island, and Spain granted Puerto Rico self-government in 1897.

Just months later, however, the United States invaded the island during the 1898 Spanish-American War as part of a broader effort to push Spain out of the Caribbean and the Pacific. Spain lost the war and ceded Puerto Rico to the United States, along with other territories, including Guam and the Philippines.

How has its relationship with the United States evolved?

A raft of legislation and court rulings in the early twentieth century forged a unique relationship between Washington and its Caribbean territory. After two years of direct U.S. military rule, the 1900 Foraker Act reestablished a civilian government and specified Puerto Rico’s territory status. While it had an elected legislature, the U.S. president appointed the island’s governor and other major officials. The Foraker Act also granted Puerto Ricans a nonvoting representative in Congress, but not citizenship. Ambiguity over the island’s status was fueled by Supreme Court cases [PDF] that declared it an unincorporated territory with no clear path to statehood.

While it had an elected legislature, the U.S. president appointed the island’s governor and other major officials. The Foraker Act also granted Puerto Ricans a nonvoting representative in Congress, but not citizenship. Ambiguity over the island’s status was fueled by Supreme Court cases [PDF] that declared it an unincorporated territory with no clear path to statehood.

By 1917, Congress had granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship, as the newly created Panama Canal increased the island’s strategic value. That spurred a wave of migration, with more than one million Puerto Ricans moving to the mainland by the mid-1960s.

Daily News Brief

A summary of global news developments with CFR analysis delivered to your inbox each morning.

Most weekdays.

View all newsletters >

In the wake of World War II and a global wave of decolonization, U.S. policymakers faced pressure to increase Puerto Rico’s autonomy. In 1946, President Harry S. Truman installed the territory’s first native-born governor. A year later, Congress granted residents permission to elect their own governors. In 1952, it approved a constitution that recast the island as a U.S. commonwealth capable of independently conducting its own affairs, including choosing its own leaders.

Truman installed the territory’s first native-born governor. A year later, Congress granted residents permission to elect their own governors. In 1952, it approved a constitution that recast the island as a U.S. commonwealth capable of independently conducting its own affairs, including choosing its own leaders.

More on:

Puerto Rico

Disasters

Economic Crises

Immigration and Migration

Puerto Rico’s economy boomed in the postwar period, with per capita income jumping by more than 500 percent between 1950 and 1971. An economic development plan known as Operation Bootstrap transformed the largely agrarian island into a manufacturing magnet, relying on federal tax exemptions, low labor costs, and other incentives to draw American companies to the territory.

What does its territory status mean?

Article 4, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution, known as the territorial clause, gives Congress broad authority to govern U. S. territories. Puerto Rico is the most populous U.S. territory. Others include American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands. They are granted various measures of self-rule, but lack their own sovereignty.

S. territories. Puerto Rico is the most populous U.S. territory. Others include American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands. They are granted various measures of self-rule, but lack their own sovereignty.

Though Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens eligible for military conscription and subject to federal laws, they lack full congressional representation. A single member of the U.S. House of Representatives, known as the resident commissioner, represents the island’s interests but has no voting power; Jenniffer González-Colón has held the position since 2017. Nor can Puerto Rico residents cast ballots in U.S. general elections, though presidential candidates curried support on the island in 2020 to win votes from the Puerto Rican diaspora in the primary race.

Puerto Rico also lacks economic sovereignty. The U.S. dollar is its currency, U.S. federal regulators oversee its businesses, and U.S. laws dictate its trade policy. Residents pay most federal taxes; their contributions totaled more than $4 billion in fiscal year 2021. However, Puerto Ricans generally do not pay federal income tax, and they continue to enjoy the tax exemptions that have historically incentivized outside investment.

However, Puerto Ricans generally do not pay federal income tax, and they continue to enjoy the tax exemptions that have historically incentivized outside investment.

Largely because of these exemptions, residents receive fewer federal benefits than other Americans. Puerto Rico residents are ineligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit and earn less, on average, in Social Security and veterans’ benefits. However, some benefits could change as a result of legal challenges. In August 2020, a district court judge ruled that denying island residents several forms of federal assistance, including Supplemental Security Income (SSI), is unconstitutional. The federal government appealed the decision, and in November 2021, the case was heard by an appeals court, which held that Puerto Rico’s exclusion from the SSI program violates the Fifth Amendment. In April 2022, the Supreme Court reversed that decision.

Like most U.S. states, the island receives billions of dollars more in federal spending, including on Medicare and Social Security, than its residents pay in taxes. In addition, the U.S. government has allocated more than $25 billion in disaster-recovery funding to the island since 2017.

In addition, the U.S. government has allocated more than $25 billion in disaster-recovery funding to the island since 2017.

What is the island’s economic outlook?

Puerto Rico continues to be ravaged by a sustained recession.

Annual economic growth fell by roughly 12.5 percent overall between 2004 and 2020, while Puerto Rico’s population shrunk by more than 16 percent. It has also struggled under a large public debt in recent years, totaling about $70 billion—or 68 percent of gross domestic product (GDP)—in 2020. Puerto Rico’s downward spiral has been compounded by natural disasters, government mismanagement and corruption, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unable to borrow on global markets, Puerto Rico was in economic limbo for years after turning over its budget to an independent control board appointed by Washington as part of a plan to restructure its debts. Making matters worse, in 2019, U.S. authorities arrested former high-level officials in a corruption scandal, leading to the resignation of Governor Ricardo Rosselló.

The island’s average household income is about one-third of the U.S. average, and its poverty rate is more than twice that of the poorest state, Mississippi. Meanwhile, the territory’s unemployment rate has stayed at almost twice the national average for the past decade, at times reaching double digits. However, it fell to about 8 percent in 2021 and has continued to drop.

What has driven the crisis?

Experts say the island’s economic crisis is rooted in [PDF] twentieth-century legislation that encouraged Puerto Rico’s reliance on debt to fill federal funding gaps. It did this by giving bond investors higher returns and loosening borrowing limits. Since 1917, lenders to Puerto Rico have been exempt from local, state, and federal taxes—the so-called triple tax exemption—effectively boosting their profits and making the island a more attractive investment. The territory’s constitution also allows Puerto Rico to balance its budget with its debt, among other provisions that facilitate borrowing.

The debt problem accelerated after 1996, when the U.S. government began phasing out Internal Revenue Code Section 936. This provision had allowed American businesses to operate tax-free in Puerto Rico, which critics viewed as a windfall for wealthy corporations. Section 936’s repeal triggered a deterioration of Puerto Rico’s manufacturing sector, and the territorial government increasingly turned to debt to cover its spending.

The 2008 global financial crisis hit Puerto Rico especially hard, with the recession further lowering tax revenues, souring an early-2000s construction boom, and giving investors pause. The territorial government implemented austerity measures, including layoffs of public workers, that sent unemployment soaring. It also crafted dubious deals to balance its budget, including letting government agencies borrow from one another to pay back bonds.

On top of that, experts say, much of this money was poorly spent. Leaders failed to parlay the billions of dollars they borrowed into strong institutions, a deficit laid bare by the natural disasters that have devastated Puerto Rico’s underfunded and poorly maintained infrastructure. Hurricane Maria brought ruin to the island in 2017, causing about three thousand deaths [PDF], knocking out the electrical power grid, and costing tens of billions of dollars. An earthquake at the start of 2020, the island’s strongest in a century, also created a power blackout. Months later, the pandemic exposed the territory’s disjointed and inefficient health system, which critics say has impeded care for COVID-19 patients. In September 2022, Hurricane Fiona triggered severe flooding and mudslides and knocked out power to more than one million homes and businesses.

Hurricane Maria brought ruin to the island in 2017, causing about three thousand deaths [PDF], knocking out the electrical power grid, and costing tens of billions of dollars. An earthquake at the start of 2020, the island’s strongest in a century, also created a power blackout. Months later, the pandemic exposed the territory’s disjointed and inefficient health system, which critics say has impeded care for COVID-19 patients. In September 2022, Hurricane Fiona triggered severe flooding and mudslides and knocked out power to more than one million homes and businesses.

The combination of government mismanagement and unrelenting natural disasters has driven an exodus from the territory, further depressing economic activity, crippling schools and other institutions, and leaving fewer taxpayers to shoulder the debt. More than 130,000 residents fled to the mainland after Hurricane Maria alone. Today, more people of Puerto Rican descent live on the mainland than on the island, and a 2019 study projected that the territory’s population would fall by another 8 percent [PDF] by 2024.

How has it dealt with the debt crisis?

Since it began defaulting on major debt obligations in 2016, Puerto Rico has struggled with how to pay its creditors—many of whom hold bonds that are protected by Puerto Rico’s constitution—while maintaining basic public services and avoiding an even deeper economic collapse. It took more than five years of negotiations for a federally appointed oversight board to approve a restructuring plan, and controversy persists.

As a territory, Puerto Rico’s options were limited from the beginning. It could not receive assistance from the International Monetary Fund, like insolvent countries such as Greece have. Neither could it file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, which municipalities such as Detroit have used to receive legal protection against creditor claims while restructuring their payments. Then there is the sheer size of the debt: Puerto Rico’s is by far the biggest government bankruptcy in U.S. history.

The island’s legislature tried to design its own restructuring process [PDF], which would have allowed public services to continue uninterrupted while it negotiated lower debt payments, but the U. S. Supreme Court rejected the law. Congress and President Barack Obama’s administration drew up an alternative plan, the 2016 Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA).

S. Supreme Court rejected the law. Congress and President Barack Obama’s administration drew up an alternative plan, the 2016 Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA).

Most notably, PROMESA created a seven-member financial oversight board appointed by the White House that was granted full control of Puerto Rico’s finances. It also created a debt restructuring process similar to Chapter 9 that governed negotiations with creditors to reduce debt payments.

Those negotiations were beset by controversy, as it became clear that all involved—bondholders, Puerto Rican pension funds, and other public services—faced steep losses. Several versions of a sweeping plan to cut the island’s debt were floated, but creditors promised legal challenges, and efforts were paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In January 2022, a federal judge approved a final plan between the PROMESA board and Puerto Rico’s government, paving the way for the island to escape bankruptcy and resume making payments to creditors. The deal cuts $33 billion in total debt obligations down to $7.4 billion, lowering Puerto Rico’s annual debt payments from nearly $4 billion to just over $1 billion. Supporters say the deal puts the island on a sustainable path while avoiding any cuts to public pensions, which had been a major point of contention.

The deal cuts $33 billion in total debt obligations down to $7.4 billion, lowering Puerto Rico’s annual debt payments from nearly $4 billion to just over $1 billion. Supporters say the deal puts the island on a sustainable path while avoiding any cuts to public pensions, which had been a major point of contention.

However, critics are wary of the resolution. Some argue that cutting debt without requiring deeper structural reforms means problems are likely to repeat. Others worry that maintaining pension obligations—which amount to $2.3 billion yearly—will prove unsustainable. Advocacy groups such as the Center for Popular Democracy say the deal will result in more economic austerity, including cuts to health care and education. They echo many critics who oppose the PROMESA process on the grounds that it undermines the territory’s already weak self-rule. PROMESA’s oversight board will remain in place until Puerto Rico meets several financial milestones—three more years at least.

Meanwhile, experts have suggested that Puerto Rico’s restructuring experience could be a test case for heavily indebted U. S. states such as Illinois and New Jersey, which are also constitutionally ineligible for bankruptcy protections.

S. states such as Illinois and New Jersey, which are also constitutionally ineligible for bankruptcy protections.

What are the arguments for changing Puerto Rico’s status?

The island’s relationship with the rest of the United States is the subject of vigorous debate. Puerto Rico’s political parties, which are distinct from the mainland’s Democratic and Republican blocs, hold different views on changing the island’s status. The five major positions are:

Status quo. Some say the U.S.-Puerto Rico relationship should remain as is. The centrist Popular Democratic Party (PPD) has historically championed the status quo, which is also called the commonwealth position.

Enhanced commonwealth. Others, including some PPD members, advocate what they call an enhanced version of Puerto Rico’s current commonwealth status. This could include allowing the island to conduct its own foreign policy and exempting it from federal law. However, U.S. officials—including a presidential task force and the Justice Department—have repeatedly dismissed this option.

Statehood. Proponents of statehood, including the island’s other major party, the New Progressive Party, say it would finally make Puerto Ricans full citizens. Additionally, the island could receive up to $12.5 billion more in federal benefits, including Medicare and Medicaid, according to recent estimates. The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the authority to create new states, though territories have no defined road to statehood, and giving Puerto Rico senators and full representatives could shift the country’s balance of power.

Independence. Puerto Rico has a long history of pro-independence movements, dating back to uprisings against Spanish and American colonial rule. Nationalists have attempted to assassinate a U.S. president, Harry Truman, and they carried out a wave of more than 130 bombings on the mainland during the 1970s and 1980s. The island’s Independence Party argues for full sovereignty, but support for that position has dwindled to single digits.

Free association. Supporters of free association envision an independent, sovereign Puerto Rico still closely linked to the United States. The federal government has similar relationships [PDF] with the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau, whose residents receive U.S. aid, military protection, and immigration benefits, but not citizenship.

Residents have weighed in on Puerto Rico’s status in six plebiscites since 1967. In November 2020, more than 52 percent of voters favored the territory’s immediate admission into the Union as a state. Roughly half of eligible voters participated in the referendum, up from only 23 percent in 2017, when inconsistent options, allegedly biased ballot language, and boycotts cast doubts on the results.

Some presidents have sought to move the needle on Puerto Rican rights and status. More recently, President Donald Trump opposed granting Puerto Rico statehood. President Biden has expressed his support for statehood, but his administration has prioritized helping the island recover. Though Congress has historically declined to pursue the matter, some House Democrats have advanced the Puerto Rico Status Act [PDF], which proposes a binding plebiscite on the territory’s status to be held in November 2023. However, the bill faces opposition from some lawmakers as well as from some Puerto Rican community leaders. Many experts say it is unlikely to advance in Congress.

Though Congress has historically declined to pursue the matter, some House Democrats have advanced the Puerto Rico Status Act [PDF], which proposes a binding plebiscite on the territory’s status to be held in November 2023. However, the bill faces opposition from some lawmakers as well as from some Puerto Rican community leaders. Many experts say it is unlikely to advance in Congress.

What else could be done?

Beyond a change in political status, Washington could do more to ease Puerto Rico’s crisis, observers say. Some have called for federal policymakers to implement an economic stimulus program, which the territorial government cannot do because of federally imposed spending restrictions. The Obama-era Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided Puerto Rico with billions of dollars in additional spending, but the ACA aid expired [PDF] in 2019.

Others propose that Congress change territory-specific policies that disadvantage Puerto Rico. The Jones Act, passed in 1920, requires goods traveling by sea between the mainland and Puerto Rico to be transported only by U. S.-built, -owned, and -operated vessels, which drives up prices on the island. Repealing it could create more than thirteen thousand jobs [PDF] and inject $1.5 billion into the economy, a 2019 study found. Meanwhile, some experts say that tax changes, including partially resurrecting Section 936, could revive Puerto Rico’s once-thriving pharmaceutical sector, stimulate the territory’s economy, and reduce U.S. dependence on international drug suppliers.

S.-built, -owned, and -operated vessels, which drives up prices on the island. Repealing it could create more than thirteen thousand jobs [PDF] and inject $1.5 billion into the economy, a 2019 study found. Meanwhile, some experts say that tax changes, including partially resurrecting Section 936, could revive Puerto Rico’s once-thriving pharmaceutical sector, stimulate the territory’s economy, and reduce U.S. dependence on international drug suppliers.

Disaster relief is another area of contention. Washington has allocated more than $68 billion in emergency aid to the island since 2017, but the Trump administration was criticized for what researchers say [PDF] was a slower, smaller federal response following Hurricane Maria compared to what states have received after natural disasters. Five years after the storm, only about one-fifth of allocated government relief funds has reached the island. After earthquakes wracked Puerto Rico in January 2020, the administration released about $16 billion in already allocated relief for the territory. However, the aid came with stringent conditions and was subject to PROMESA oversight. That September, the Trump administration announced almost $13 billion in new aid to repair Puerto Rico’s hurricane-ravaged electrical grid and schools.

However, the aid came with stringent conditions and was subject to PROMESA oversight. That September, the Trump administration announced almost $13 billion in new aid to repair Puerto Rico’s hurricane-ravaged electrical grid and schools.

Puerto Rico has also benefited from the federal COVID-19 stimulus. However, experts have urged Washington to authorize additional aid that accounts for gaps in Puerto Rico’s social safety net, which are linked to its status as a territory, and the island’s prepandemic crises. During his presidential campaign, Biden released a plan to ease Puerto Rico’s multilayered crisis, including by facilitating reconstruction; reducing the territory’s debt burden; and expanding access to and funding for social services. In April 2021, Biden freed up more than $8 billion in disaster-relief funding for Puerto Rico, and in July, his administration revived a White House task force to better coordinate federal policy toward the island. In the days following Hurricane Fiona, Biden declared an emergency, dispatched hundreds of federal employees to the island, and announced that Washington would cover a month of aid spending.

Puerto Rico Island – Islands of the World

Map of the island of Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico Island (Spanish version – Puerto Rico) – an island that is part of the Greater Antilles archipelago and located to the east of the island of Haiti (Hispaniola) about 100 kilometers. The island of Puerto Rico is washed in the south by the waters of the Caribbean Sea, and in the north by the open Atlantic Ocean. It is separated in the east from the Virgin Islands by the Virgin Strait, and in the west – from the island of Haiti (Hispaniola) by the Mona Strait. The origin of the name of the island is more than incidental. The Spaniards originally named the island San Juan Bautista in honor of Saint John the Baptist, and the largest settlement on the island is Puerto Rico, which translates as “Rich Port”. However, when making maps of the Caribbean region, an error was made in which the city was designated as San Juan, and the island as Puerto Rico. Subsequently, when the error was revealed, the erroneous name of the island of Puerto Rico stuck to it quite firmly, and it was decided not to change it.

Subsequently, when the error was revealed, the erroneous name of the island of Puerto Rico stuck to it quite firmly, and it was decided not to change it.

The geographical coordinates of the island of Puerto Rico are determined by its conventional geographical center: 18°13′08″ N.S. sh. 66°34′24″ W e.

Puerto Rico has an area of more than 9,000 square kilometers.

Puerto Rico and the adjacent Spanish Virgin Islands currently contain an unincorporated organized territory of the United States called the Freely Associated State of Puerto Rico.

NASA satellite image of Puerto Rico.

History.

Archaeologists say that the first orthoroid people appeared on the island of Puerto Rico around 2000 BC. Between 100 and 400 AD, representatives of the Igneri Indian tribes began to arrive in Puerto Rico from the Orinoco River region in South America, and between the 7th and 11th centuries, Arawak tribes began to penetrate the island, who founded the Taino culture here. .

.

For Europeans, the island of Puerto Rico was discovered by Christopher Columbus on November 19, 1493, who landed on land on the same day.

Spanish colonization of Puerto Rico began in 1508. During this period, from the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo on the island of Haiti (Hispaniola), a detachment of conquistadors arrived under the command of Juan Ponce de León, who easily conquered the local Indian tribes and founded the fortified city of Caparra.

The Indian population of the island was quickly exterminated, so in return, the Spaniards began to import slaves from Africa to work on plantations and mines.

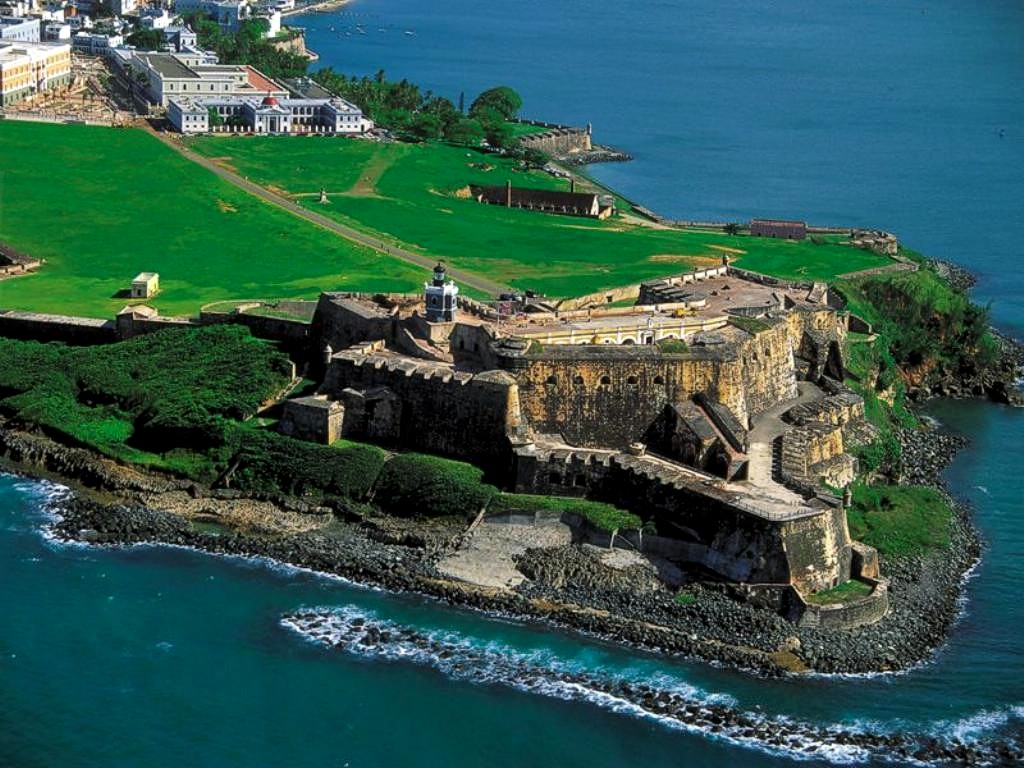

In the period of the XVII-XVIII centuries, in order to protect against French and British pirates, such fortresses as La Fortaleza (La Fortaleza), Fuerte San Felipe del Morro (Fuerte San Felipe del Morro), San – Cristobal (Fuerte San Cristóbal) and others.

On July 25, 1898, almost immediately after the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, American troops landed on the island of Puerto Rico. Encountering no resistance from the Spanish army, the island is quickly captured, and according to the Treaty of Paris 189For 8 years already legally, together with the Philippines, Guam and Cuba, it has been ceded to the United States.

Encountering no resistance from the Spanish army, the island is quickly captured, and according to the Treaty of Paris 189For 8 years already legally, together with the Philippines, Guam and Cuba, it has been ceded to the United States.

In 1917, all interested residents of Puerto Rico were granted US citizenship, and in 1947, the American authorities allowed Puerto Ricans to choose their own governor.

Beginning in the 60s of the last century, a separatist movement for the independence of Puerto Rico under the leadership of Filiberto Ojeda Rios, incited by Cuba and the USSR, is rising, and episodes turn into an armed confrontation with the authorities.

On November 6, 2012, a referendum was held on the island, according to which the majority of the inhabitants of Puerto Rico spoke in favor of joining the island as part of the United States as a full state.

Currently, the island of Puerto Rico is a major tourist center in the Caribbean region with an economy that, in addition to tourism, is also based on the pharmaceutical, food, processing and engineering industries.

East coast of Puerto Rico.

Origin and geography of the island.

The island of Puerto Rico, like the neighboring islands of Haiti (Hispaniola), Cuba and Jamaica, is a surface part of the North Caribbean submarine mountain range, which rose at the boundary of the collision of three geological plates. Numerous experts classify Puerto Rico, like other islands in the Greater Antilles archipelago, as volcanic. Their formation by specialists dates back to the period of the early Miocene, which is about 6-7 million years distant from our time.

There are many smaller islands and reefs off the coast of Puerto Rico. Among the large and significant islands are the islands of Mona (Isla de Mona) and Desecheo (Desecheo) to the west of Puerto Rico, Caja de Muertos (Caja de Muertos) – to the south, Vieques (Vieques) and Culebra (Culebra) – to the east. The latter two are part of the Spanish Virgin Islands and are geologically the western part of the Virgin Islands. It is they of all the islands listed above that have a permanent population. Other offshore islands and reefs are uninhabited, while Mona Island is inhabited only by employees of the Puerto Rican Ministry of National Resources and visiting tourists.

It is they of all the islands listed above that have a permanent population. Other offshore islands and reefs are uninhabited, while Mona Island is inhabited only by employees of the Puerto Rican Ministry of National Resources and visiting tourists.

The island of Puerto Rico is almost rectangular in shape, about 170 kilometers long and 60 kilometers wide. The coastline is quite even and does not form deep bays protruding into the land. However, small and convenient bays for mooring are observed almost along the entire length of the coast.

The island of Puerto Rico is mostly mountainous, but with large coastal flat areas in the north and south. The main mountain system of the island of Puerto Rico is called La Cordillera Central, which translates as “Central Range”. It is in its composition that the highest point of the island is located – Mount Cerro de Punta (Cerro de Punta), towering 1338 meters above sea level. Mount El Yunque, 1065 meters high, should also be attributed to the number of significant mountains of the island.

The rivers on the island of Puerto Rico are not too deep and long. Most of them empty into the Atlantic Ocean in the north. Among the most significant of them, it is worth noting San Sebastien, Araiva, Amalina, Los Jimenas and others.

Tourist area on the west coast of the island of Puerto Rico.

Climate.

The climate on the island of Puerto Rico should be classified as a tropical maritime type. It is characterized by softness with slight seasonal temperature fluctuations. In the south of the island it is a little hotter than in the north, and in the Central Range area it is always a little cooler than on the coast. The average annual air temperature in Puerto Rico is approximately +28°C. It is worth noting that the probability of hurricanes is very high here, especially between the beginning of June and the end of November. A rather powerful hurricane, dubbed “Hortensia”, on September 1996 led not only to catastrophic destruction, but also to numerous human casualties. It rains in Puerto Rico from early May to October. For the most part, these are short-term showers. It is worth noting that even at this time, solar activity does not fall and remains virtually at the same level as during dry periods. On the east coast, there is more precipitation due to moist winds that blow on the island, usually from the northeast.

It rains in Puerto Rico from early May to October. For the most part, these are short-term showers. It is worth noting that even at this time, solar activity does not fall and remains virtually at the same level as during dry periods. On the east coast, there is more precipitation due to moist winds that blow on the island, usually from the northeast.

Panorama of the city of San Juan.

Population.

Puerto Rico has a population of over 3,700. According to the ethnic composition, it is conditionally divided into immigrants from Europe, mainly from Spain, the population of African origin and Indians. This division is very conditional, since over the many years of successful coexistence of various ethnic groups on the island, the peoples and races in Puerto Rico have mixed so much that it is sometimes impossible to determine the nationality of a particular inhabitant.

The official and most spoken languages on the island are English and Spanish.

The administrative center of the island, as well as the entire territorial entity of Puerto Rico, is the city of San Juan, located on the northeast coast. Currently, about 400 thousand inhabitants live in the city. Other significant settlements of the island include the cities of Aguadilla, Arecibo, Cayel, Fajardo, Mayaguez, Caguas, Ponce and others.

The island of Puerto Rico and its adjacent islands are part of an unincorporated organized territory of the United States and are the Freely Associated State of Puerto Rico. General administrative management is carried out by the governor, who is elected by the inhabitants of this territorial entity. Puerto Rico also consists of 78 municipalities, divided into districts, which in turn are divided into sectors. Each municipality elects its own mayor for four years and manages it locally.

The unit of currency in circulation in the Free Associated State of Puerto Rico is the United States dollar (USD, code 840), which is divided into 100 cents.

Promenade along the wall of the old fortress in the city of San Juan.

Flora and fauna.

Flora and fauna of Puerto Rico are quite diverse. So, based on data as of 1998, 239 species of various plants grew in Puerto Rico. The fauna as of this period also consisted of 16 species of birds, as well as 39endemic species of amphibians and reptiles. The so-called “Rico” frogs that live here, which are also called “coquis” (Eleutherdactylus coqui), are the unofficial symbol of the island. These creatures live in large numbers in tropical rainforests, which are called the Caribbean National Forest “El Yunque” (El Yunque).

A large number of ferns grow in the tropical forests of the island, the number of varieties of which exceeds a hundred, as well as orchids. Due to the huge diversity of flora, El Yunque currently has the status of a biosphere reserve under the protection of the UN.

To the west of El Yunque is a similar biosphere reserve, Guánica, which covers tropical dry forests.

In the coastal areas of the island, mangrove forests are of the greatest naturalistic value.

“El Yunque” tropical rainforest in central Puerto Rico.

Tourism.

Tourism in Puerto Rico is perhaps the main source of income for the local treasury. There are almost all conditions for the development of the tourism sector on the island. This is a fabulous nature that endowed the island with a mild tropical climate, clean white sand beaches and azure coastal waters, and a developed infrastructure, including a network of international air and sea ports, luxurious hotels and a complex of entertainment facilities for tourists and guests of the island.

Most tourists visit Puerto Rico in January, February and March, when it is dry, warm and sunny. These are sailing enthusiasts, and windsurfers, and divers diving to the massive coral reef on the south coast.

The relatively high cost of services on the island makes it not very attractive for Europeans to rest on it. For that, there are always a lot of Americans here, who make up the vast majority of vacationers.

For that, there are always a lot of Americans here, who make up the vast majority of vacationers.

Beaches on the south coast of Puerto Rico.

Tags: Eleutherdactylus coqui, Isla de Mona, Juan Ponce de León, La Cordillera Central, Puerto Rico, Aguadilla, Amalina, Araiva, Arecibo, archipelago, Atlantic Ocean, windsurfing, Virgin Islands, geographical coordinates, geological plate, Mount Cerro Cerro de Punta, El Yunque mountain, Guanica, governor, diver, US dollar, Spain, Spanish-American war, Spanish Virgin Islands, history, Caguas, Cayel, Caparra, Caribbean Sea, climate, colonization, coral reef, Cuba, La Fortaleza, Los Jimenas, Mayagüez, municipality, mayor, population, UN, Orinoco, Vieques island, Haiti (Hispaniola), Guam island, Deseceo island (Desecheo), Caja de Muertos Island, Culebra Island, Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island, San Juan Bautista Island, Igneri Tribes, Plaza, Ponce, Virgin Sound, Mona Strait, Puerto Rico, referendum, San Cristobal (Fuerte San Cristóbal), San Sebastien , San Juan, Santo Domingo, Freely Associated State of Puerto Rico, Saint John the Baptist, USSR, USA, Taino, territory, tourism, pharmaceuticals, fauna, Fajardo, Filiberto Ojeda Rios, Philippines, flora, Fuerte San Filipe del Morro (Fuerte San Felipe del Morro), ridge, Christopher Columbus, Juana Ponce de Leon, cent, South America, Jamaica

Puerto Rico: Ponce – Mangrove Island

8:30 – 10:00

Pick up and drive to Ponce, the “southern capital” of Puerto Rico. On the way – a story about the national traditions and customs of Puerto Rico.

On the way – a story about the national traditions and customs of Puerto Rico.

10:00 am – 12:00 pm

Meet and tour of downtown Ponce with a local Russian speaking guide (visiting the historic city center, an ancient fire station and a folk music museum)

Ponce is a major port and the second largest port city of Puerto Rico – located in the southern part of the island, between the mountain range Cordillera Central and Caribbean coast . The city, often referred to as La Perla del Sur (“Pearl of the South”), was founded by Spanish settlers in 1692. Today, the city center – its cozy squares, churches, ornate colonial houses and graceful fountains of the colonial period – is considered a National Historic Treasure.

The majestic Cathedral of our Lady of Guadeloupe, which dominates the city landscape at Las Delicias (Plaza las Delicias/Plaza of Delights).

Directly behind the cathedral, on the square, is the building of the fire station ( Parque de Bombas ). It is one of the most striking pieces of architecture in Puerto Rico and is even considered by some to be the most easily recognizable symbol of the island. For many years, the building housed the central fire station, and currently houses a historical museum. The building has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984.

12:00 – 13:00

Transfer west from Ponce to Guanica.

13:00 – 14:30

Lunch – tourists pay for their own lunch, the guide talks about typical local dishes. Transfer by ferry to the mangrove island (for particularly athletic travelers, you can arrange a swim to the island in kayaks – it takes about 30 minutes of active rowing one way, kayaks are rented by the hour and are paid separately).

14:30 – 16:30

A visit to a unique mangrove island surrounded by clear water and many tiny tropical fish that trustfully swim up to bathing beachgoers.