Puerto rican community: About the Puerto Rico Community Survey

Puerto Rico; un pueblo diaspórico

|

Csar J. Ayala

haga clic para versión en español

In 2018, 64 percent of all Puerto Ricans lived in the 50 states and in the District of Columbia, while the remaining 36 percent lived in Puerto Rico. At the turn of the 21st century, the population of Puerto Rico was still slightly larger than the Puerto Rican population stateside. The Puerto Rican population in the continental United States surpassed that of the Island in 2006, the same year in which the 936 tax exemptions to industry expired in Puerto Rico, accelerating the exodus propelled by the loss of manufacturing jobs. The tax exemptions to industry provided by section 936 of the U.S Internal Revenue Code were phased out gradually during 1996-2006, causing a catastrophic drop in manufacturing employment in Puerto Rico.

Source: Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org )

The Puerto Rican economy, which was never able to provide enough employment to the population throughout the 20th century, began to collapse as a result of the elimination of section 936. By the time the population figures of the 2020 Census are released, in all probability two thirds of Puerto Ricans will be located stateside, one third in the Island. At present, the Puerto Ricans are a diasporic people.

The increase in the Puerto Rican population in the continent happened simultaneously with an absolute decrease of the population of the Island. Puerto Rico had more population in 2000 than it has today. The great exodus of the last two decades differs from the migration of Puerto Ricans in the 1950s in that the previous migratory wave did not produce an absolute decline of the population, but rather a slowdown of the increase in population in the Island. There was positive population growth despite the large number of Puerto Ricans that left for the United States every year.

Source: US Census, American Community

The migratory flow of the last two decades is also different from the migration of the 1950s in terms of the destination of the migrants. The great receiving magnet for Puerto Ricans in the 1950s was New York City, followed by Philadelphia and Chicago. In the 21st century, the principal destination for Puerto Ricans is the state of Florida, which today houses the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans, having surpassed New York state. In 2018, 1,073,673 Puerto Ricans lived in the state of New York, which is 29,738 less than in the year 2000. During this same period the Puerto Rican population of Florida increased by 692,939, reaching a total of 1,171,637 in 2018.

There are other states in which the Puerto Rican population experienced significant growth between 2000 and 2018. In Pennsylvania the increase amounted to 269,282, bringing the total Puerto Rican population to 472,213. In Texas the increase of 129,368 brough the total up to 213,809, while in the Commonwealth of Massachussets the increase amounted to 124,182, pulling the total upwards to 329,532 in the year 2018. The Puerto Rican population in the 50 states, which will soon reach 6 million, is distributed as indicated in the table at the end of this note.

These demographic indicators raise many questions.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

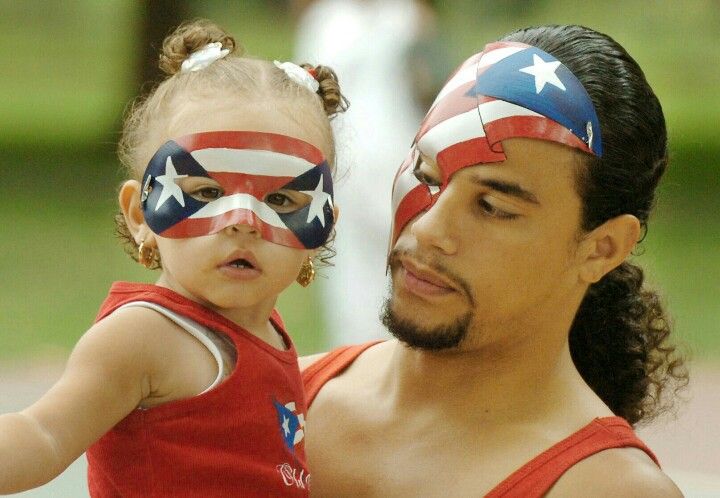

The Puerto Rican Community – The Faces of Gentrification

The 1960s saw a spike in Puerto Rican Immigration to Williamsburg. The new immigrants sought out this area as a means for jobs, as there were many factories in the surrounding area and it would be easy for them to find work in places such as the Domino Sugar Factory and Refinery. (bklynlibrary.org) But the Puerto Rican community has been present in the neighborhood of Williamsburg since as early as the 1920s. They even have a street named for them, Graham Avenue, or “Avenue of Puerto Rico” located at the south end of the block. (baruch.cuny.edu) At the time of World War II, a second wave of Puerto Rican Immigrants found their way into Williamsburg and this area became an established Puerto Rican community and cultural “hub”. (southsidewilliamsburgproject.weebly.com) The Southside of Williamsburg’s streets became a flourishing Puerto Rican neighborhood, bringing about the emergence of many cultural and structural icons of Williamsburg’s history. The increase of these residents brought into action a plan for the Metropolitan Pool and Bath, a pool that is still extremely popular to Williamsburg natives today. During this time, many working class citizens are living in this area, with jobs revolving around the factories present in the neighborhood at this time. This southside area inhabited by Puerto Ricans became known as “Los Sures” or, in English, “The Souths”.

(bklynlibrary.org) But the Puerto Rican community has been present in the neighborhood of Williamsburg since as early as the 1920s. They even have a street named for them, Graham Avenue, or “Avenue of Puerto Rico” located at the south end of the block. (baruch.cuny.edu) At the time of World War II, a second wave of Puerto Rican Immigrants found their way into Williamsburg and this area became an established Puerto Rican community and cultural “hub”. (southsidewilliamsburgproject.weebly.com) The Southside of Williamsburg’s streets became a flourishing Puerto Rican neighborhood, bringing about the emergence of many cultural and structural icons of Williamsburg’s history. The increase of these residents brought into action a plan for the Metropolitan Pool and Bath, a pool that is still extremely popular to Williamsburg natives today. During this time, many working class citizens are living in this area, with jobs revolving around the factories present in the neighborhood at this time. This southside area inhabited by Puerto Ricans became known as “Los Sures” or, in English, “The Souths”. (ny.curbed.com)

(ny.curbed.com)

The Puerto Rican community has thrived in Williamsburg since the 1920s, contributing a vibrant culture to the neighborhood in their time there. Puerto Rican restaurants, stores and flags crowded the streets of the southside. However, in the early 2000s, things began to take a turn for the Puerto Rican as well as the Hispanic community in general calling Williamsburg their home. A new art community was forming and unfortunately, at the expense of the Puerto Rican culture already present there. A gentrification was occurring on the streets of Brooklyn and especially Williamsburg. People noticed the cheap prices and proximity to Manhattan and began moving in. Soon, stores popped up accommodating those artists, their budgets and their preferences. Restaurants, supermarkets, and stores, all of these things began to take a sudden change. Prices increased, rent increased and the Puerto Rican community decreased. In 2000, 4,036 Hispanics lived on the southside of Williamsburg and in 2010, 3,459 remained. (Center of Urban Research of CUNY)

(Center of Urban Research of CUNY)

This not only caused a serious rift in the Puerto Rican culture that had previously thrived in Williamsburg but it also introduced a new social stratification to the area. The Puerto Ricans and other hispanics became the “poor” and those moving in became the “rich”. The north was where the “wealthy” people lived and the south was for the “lower class”. Prior to this, Williamsburg had been home to working class people, pursuing the American Dream. (http://larespuestamedia.com)

Due to these social and economic changes occurring within the neighborhood, a lot of other things have changed as well. Prices have risen, rent has increased drastically and local businesses have lost income due to newer, swanky stores opening every week. Gentrification in the area has affected a community of people who have lived in a working class, struggling, but culturally rich neighborhood for many years.

Mexican society | History of Mexico | Henry Bamford Parkes

Mexico was destined to eventually become the home of a new nation, born from the union of two races with different characters and traditions. During the colonial period, under the careless and despotic rule of the viceroys, the Spaniard and the Indian slowly drew closer. Indian habits and the influence of the Mexican environment softened the initial gloominess and severity of the Creoles. Spanish customs and beliefs merged with the traditions of Indian villages. A new mixed race – mestizos – became more and more numerous.

During the colonial period, under the careless and despotic rule of the viceroys, the Spaniard and the Indian slowly drew closer. Indian habits and the influence of the Mexican environment softened the initial gloominess and severity of the Creoles. Spanish customs and beliefs merged with the traditions of Indian villages. A new mixed race – mestizos – became more and more numerous.

The Mexican population was divided into four different castes: Gachupins, Creoles, Mestizos and Indians. The aristocratic passion for subtle differences led to the fact that the category of mestizos was subdivided into 16 groups, representing various combinations of Spanish, Indian and Negro origin.

The growth of the Mexican nation and the mestizo struggle for power will be a slow and painful process, a process punctuated by periods of anarchy and dictatorship, revolutions and civil wars. However, already in the colonial period, the qualities inherent in the new nationality affected. Mexican society acquired its own individual character, which could not be called either Indian or Spanish, but only Mexican. The whole country was imbued with the old Mexican love for music, colors and colors. On city streets, singers played the marimbas (a kind of primitive xylophone) and sang songs (corridos) in honor of popular heroes. In the evenings, uneducated rancheros and shepherds (vaqueros) gathered in the villages and improvised verses, choosing melodies for them on the guitar. Artists depicted bullfights or episodes from the life of saints on the walls of pubs (pulquerias) and sold images of miraculous rescues from accidents or healings from illnesses. Spread under the tropical sun, under the sky, against the backdrop of an endless vista of blue mountains, Mexican cities with their wide, straight streets, white or red houses, with their courtyards (patios) decorated with roses and orange trees, towers of churches and monasteries, with Indian markets and garishly painted squash, presented a beautiful picture, which was not equal in all of America.

Mexican society acquired its own individual character, which could not be called either Indian or Spanish, but only Mexican. The whole country was imbued with the old Mexican love for music, colors and colors. On city streets, singers played the marimbas (a kind of primitive xylophone) and sang songs (corridos) in honor of popular heroes. In the evenings, uneducated rancheros and shepherds (vaqueros) gathered in the villages and improvised verses, choosing melodies for them on the guitar. Artists depicted bullfights or episodes from the life of saints on the walls of pubs (pulquerias) and sold images of miraculous rescues from accidents or healings from illnesses. Spread under the tropical sun, under the sky, against the backdrop of an endless vista of blue mountains, Mexican cities with their wide, straight streets, white or red houses, with their courtyards (patios) decorated with roses and orange trees, towers of churches and monasteries, with Indian markets and garishly painted squash, presented a beautiful picture, which was not equal in all of America.

The city of Mexico, the residence of the viceroys and the main center of luxury and elegance of the Creoles, was until the 19th century. large and beautiful city in the Western Hemisphere. In the XVIII century. it was no longer an island. Deforestation reduced the amount of water in the valley, and the viceroys built a canal in the mountains to prevent floods, which drained some of the lakes, diverting water from them into the Tula valley and the Panuko River. In the center of the city there was a large square, once the temple area of the Aztecs, now bordered by a cathedral, a palace of viceroys and a town hall. To the west, past the monastery of St. Francis, was the main street of the business district of Calle de Plateros [1] (Silversmiths Street), leading to the poplars, fountains, and cobbled paths of the Alameda, beyond which stretched the willow-lined Paseo driveway.

No less magnificent were the aristocrats themselves – the Creoles and Gachu Pins, who constituted the most important part of the population of Mexico City. Every evening at five o’clock, carriages of wealthy ladies dressed in Chinese silks moved along the Paseo; they were surrounded by riders, whose horses were adorned with bridles and bridles heavy with silver, and leather blankets from which hung silver bells. The cavaliers wore wide sombreros hats, silk jackets with gold embroidery, green or blue pantaloons open at the knees and decorated with silver buttons, and huge silver spurs. In the evening, having changed their entire costume, the ladies and their gentlemen met in the theater or danced at a masquerade, where the ladies appeared in purple or yellow dresses and green or pink shoes. During the summer, Creole families would retire to country houses nestled among the fruit orchards of San Angel. And in August, on the day of St. Augustine, the entire population of the city gathered in Tlalpama, where rich ladies sat next to beggars and thieves and spent their days gambling heaps of silver or enjoying cockfights, and their evenings in dancing.

Every evening at five o’clock, carriages of wealthy ladies dressed in Chinese silks moved along the Paseo; they were surrounded by riders, whose horses were adorned with bridles and bridles heavy with silver, and leather blankets from which hung silver bells. The cavaliers wore wide sombreros hats, silk jackets with gold embroidery, green or blue pantaloons open at the knees and decorated with silver buttons, and huge silver spurs. In the evening, having changed their entire costume, the ladies and their gentlemen met in the theater or danced at a masquerade, where the ladies appeared in purple or yellow dresses and green or pink shoes. During the summer, Creole families would retire to country houses nestled among the fruit orchards of San Angel. And in August, on the day of St. Augustine, the entire population of the city gathered in Tlalpama, where rich ladies sat next to beggars and thieves and spent their days gambling heaps of silver or enjoying cockfights, and their evenings in dancing. The fortunes in New Spain were made chiefly in the mines; therefore, in Creole society there has always been something of the carelessness and barbaric boastfulness of the inhabitants of the mining village.

The fortunes in New Spain were made chiefly in the mines; therefore, in Creole society there has always been something of the carelessness and barbaric boastfulness of the inhabitants of the mining village.

By the end of the 18th century. in Mexico there were about a million people who claimed to be Creoles, although many of them had Indian blood in their veins. During the time of the conquistadors, mixed marriages were frequent. The removal of the Creoles from power was justified on the grounds that they were an “inferior race”. The American environment was supposed to lead to degeneration. There was a grain of truth in this theory. The Creoles were generous, amiable and sometimes cultured, although they also had a tendency to laziness, licentiousness and frivolity. Of course, the reason for their degeneration was not the climate, but the fact that the possession of mines and haciendas or paid positions in the church and state apparatus gave them the opportunity to live in luxury, and due to the policy of the Spanish government they were not entrusted with any responsible affairs. Their favorite pastimes were playing cards and love affairs, and their entertainment was attending bullfights and cockfights. Instead of rebelling against the Gachupins, they slavishly imitated their habits. Many Creoles sought minor positions in the administrative apparatus, and the viceroys were very willing to satisfy their passion for rank by selling them positions. The cities of New Spain were teeming with petty officials who had no power or duties, but who enjoyed the prestige that belonged to the bureaucracy gave them. Toward the end of the XVIII century. a new field of activity opened up for them: an army was organized to protect New Spain from a possible English invasion. The ordinary soldiers of this army were mestizos or mulattoes, and the officers were Creoles. The officers, shining in their blue and white uniforms, who, like the clergy, enjoyed the fuero (privilege) to sue only in military courts, soon became accustomed to considering themselves an independent and privileged caste.

Their favorite pastimes were playing cards and love affairs, and their entertainment was attending bullfights and cockfights. Instead of rebelling against the Gachupins, they slavishly imitated their habits. Many Creoles sought minor positions in the administrative apparatus, and the viceroys were very willing to satisfy their passion for rank by selling them positions. The cities of New Spain were teeming with petty officials who had no power or duties, but who enjoyed the prestige that belonged to the bureaucracy gave them. Toward the end of the XVIII century. a new field of activity opened up for them: an army was organized to protect New Spain from a possible English invasion. The ordinary soldiers of this army were mestizos or mulattoes, and the officers were Creoles. The officers, shining in their blue and white uniforms, who, like the clergy, enjoyed the fuero (privilege) to sue only in military courts, soon became accustomed to considering themselves an independent and privileged caste.

Outside the cities, the valleys of Central and Southern Mexico were dotted with huge white houses where Creole landowners lived in solitary splendor. They owned estates stretching over hundreds of 90,003 90,004 square miles of mountains and forests, where herds of bulls, sometimes several hundred thousand heads, grazed. The landlords spent their time on horseback, hunting, shooting, and supervising the peons who worked in the wheat fields or sugarcane plantations. The traveler who disturbed their solitude was received with Castilian courtesy and entertained with a bullfight, a picnic with music, or a demonstration of the dexterity of the vaqueros shepherds who caught the master’s bulls. Only in the far north, in the steppes of Durango, Sonora and Chiguagua, so remote from Mexico City and so inaccessible that almost nothing was known about them, did a more democratic society emerge. It was the land of energetic and industrious Creole and Mestizo ranchers, working their own land and grazing herds of sheep and goats on the hills.

Three or four million Indians lived almost the same as their ancestors before the conquest. In the fertile lands of the valleys of the central provinces, many of the Indians became peons in haciendas. Some outlying mountain villages have retained communal lands (ejidos). In the deserts of the north, wild tribes roamed, raiding Spanish settlements. Peons, like independent peasants, almost did not succumb to the influence of Spanish culture. True, Spanish influences appeared from time to time in their food and clothing, tools and utensils. The religion of the Indians turned into a mixture of paganism and Catholicism. But in its main features, the way of life of the Indians has not changed. They continued to eat cakes, peppers and beans. The Oki still built huts for themselves out of wood, mud, or unhewn stone, and spread their straw mats on the bare ground. They did not eat beef, lamb, wheat bread, did not drink wine, did not wear woolen or silk fabrics. They still planted maize with pointed sticks, baked it on coals, obeyed their caciques, and spoke the old tribal languages.

The Spanish conquest caused great damage to Indian culture. But under Spanish rule, it was often useless for the Indians in the villages to show industriousness and intelligence. Every village that produced more than needed for a meager existence could seduce the greedy corregidor. In Mexico, there was evidence of the talents inherent in the Indian peoples. But Palenco and Chichen Itza were buried in impenetrable forests, the pyramids of Teotihuacan turned into grass-covered hills, the site of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl could be recognized only by a few oddly shaped mounds, and the ruins of Tenochtitlan were hidden under the cathedral and the square of the Spanish city.

The best works of Indian culture were destroyed. Temples were destroyed, pyramids demolished, idols burned, colleges of priests disbanded. The burning of Indian manuscripts attributed to Sumarraga seems not to have taken place [2] ; on the contrary, some of the more enlightened clerics tried to preserve Indian pictographic writing, but soon there were no Indians able to read them. The science of Mexico before the Spanish conquest became a closed book. But although the superstructure of the old society has disappeared, its basis – the economic and social organization – has been preserved. Under the Spanish yoke, the Indian society was crushed, but not killed. In the XX century. the Indians will meet the Creoles on an equal footing – not as an inferior race, but as the heirs of the Maya and the Aztecs.

The science of Mexico before the Spanish conquest became a closed book. But although the superstructure of the old society has disappeared, its basis – the economic and social organization – has been preserved. Under the Spanish yoke, the Indian society was crushed, but not killed. In the XX century. the Indians will meet the Creoles on an equal footing – not as an inferior race, but as the heirs of the Maya and the Aztecs.

During the colonial period, the intermediate race, the mestizos, were in almost the same predicament as the Indians. In the XVI century. racial mixing was tolerated, but later, when the racial prejudices of the Creoles increased, the mestizos were deprived of the privileges of the winning race, and at the same time they were even forbidden to live in Indian villages so that they would not incite the inhabitants to rebellions. Some mestizo families became actually Indian. Other mestizos became muleteers, ranchers, or found work in the mines and in industry, and in the 16th! began to infiltrate the ranks of the lower clergy. But a mestizo born out of wedlock could only choose between begging or robbery. In Spanish cities, a huge population of tramps (leperos) gradually appeared. In the city of Mexico alone, there were 15-20 thousand of them. Homeless and half-naked, they crowded the streets and squares. During the day they begged for alms, and under the cover of night they were capable of robbery and murder.

But a mestizo born out of wedlock could only choose between begging or robbery. In Spanish cities, a huge population of tramps (leperos) gradually appeared. In the city of Mexico alone, there were 15-20 thousand of them. Homeless and half-naked, they crowded the streets and squares. During the day they begged for alms, and under the cover of night they were capable of robbery and murder.

By begging or stealing a few reais, they could satisfy their thirst for pulque, and every night wagons circled the city, picking up drunks and taking them to prison. The most energetic of these pariahs organized robber bands in the mountains. For centuries, the main trade routes were teeming with bandits, who excelled in their inherent cruelty, but sometimes became the legendary heroes of the Indian villages – they were told that they steal from the rich in order to generously give gifts to the poor. In the XVIII century. A special police force was organized – “akordada” – with the right to carry out the death penalty. Whoever fell into her claws was immediately crucified, and the decaying corpses of the crucified adorned the roads as a warning to all those passing by.

Whoever fell into her claws was immediately crucified, and the decaying corpses of the crucified adorned the roads as a warning to all those passing by.

Nevertheless, it was the mestizos who were to create the Mexican nation in the future. A man of dubious origin, with indeterminate connections, the mestizo possessed a volcanic energy very different from the slowness of the Creole, as well as from the passivity of the Indian. Resenting the Spanish claim to superiority, he inherited enough Spanish individualism to fight them. The Mestizos were a revolutionary force that was to play a leading role in the struggle against the Spanish government and Spanish institutions. By the end of the XVIII century. this category was 2 million people. and continued to grow, so that it seemed likely that it would absorb both the full-blooded Creole and the full-blooded Indian[3].

[1] Now part of Francisco Madero’s umsha.

[2] However, in Yucatan Bishop Landa burned Maya manuscripts.

[3] Mestizos of Mexico were a social rather than an ethnic category. In any case, the features of the mestizo population of Mexico in the 18th century. were due precisely to his inferior social position, and not to some kind of “racial character” (Ed. note)

Mexico urged its citizens to follow US migration policy

https://ria.ru/20170211/1487728311.html

Mexico urged its citizens to follow US migration policy

Mexico urged its citizens to follow US migration policy – RIA Novosti, 02/11/2017

Mexico urged its citizens to follow the US migration policy

The Mexican Foreign Ministry called on the citizens of their country who are in the United States to take preventive measures and follow the American migration policy… RIA Novosti, 02/11/2017

2017-02-11T04:21

2017-02-11T04:21

2017-02-11T06:52

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

2 /html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

USA

Mexico

RIA Novosti

1

5

4. 7

7

96

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA “Russia Today”

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn-p1ai/Awarts/

2017

RIA

1

5,000,0002 4000 4000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 4

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https: //xn—c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96 96

9000 7 495 64 646 646 64 64 646 64 646 64 646 646 646 646 646 646 645 646 646 645 645 64 645-66002 FSUE MIA “Russia Today”

https: //xn—C1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/Awards/

1920

1080

TRUE

1920 9000 1440

True

HTTPS: // CDNANNANNAL img.ria.ru/images/103882/42/1038824259_175:0:2987:210

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og. xn--p1ai/awards/

xn--p1ai/awards/

in the world, USA, Mexico

in the world, USA, Mexico 9002 MOSCOW, February 11 – RIA Novosti. The Mexican Foreign Ministry called on citizens of their country who are on US soil to take preventive measures and monitor US migration policy after reports of the deportation of a Mexican citizen.

Media: Mexican Foreign Minister changed Trump’s speech about building Wall

NaN , NaN:NaN

“The case of Ms. Guercia de Reyos demonstrates the new reality that the Mexican community in the United States is living in after the introduction of stricter measures to control migrants. As such, we urge the entire Mexican community to take precautions and is in closer contact with the consulates in order to receive the necessary assistance in confronting situations of this kind,” the Foreign Ministry said in a statement.

Trump wall on the US-Mexico border will cost $21.

06%

06% 38%

38% In the current wave, however, the exodus is compounded by the decline in natality rates, resulting in the shrinkage of the population from 3,810,605 inhabitants in 2000 to 3,193,354 in 2018, a reduction of 16%. One could say that one of every six inhabitants has left the Island.

In the current wave, however, the exodus is compounded by the decline in natality rates, resulting in the shrinkage of the population from 3,810,605 inhabitants in 2000 to 3,193,354 in 2018, a reduction of 16%. One could say that one of every six inhabitants has left the Island. Two thirds of the increase in Florida in the period 2000-2018 was due to inflows from other U.S. states (452,462), while one third was due to an inflow of residents of Puerto Rico (240,472). Overall, the two states with the greatest concentrations of Puerto Ricans, Florida and New York, account for almost 40 percent of the 5,771,813 Puerto Ricans who lived stateside in the year 2018.

Two thirds of the increase in Florida in the period 2000-2018 was due to inflows from other U.S. states (452,462), while one third was due to an inflow of residents of Puerto Rico (240,472). Overall, the two states with the greatest concentrations of Puerto Ricans, Florida and New York, account for almost 40 percent of the 5,771,813 Puerto Ricans who lived stateside in the year 2018. What is the significance of the fact that two thirds of Puerto Ricans now live outside Puerto Rico? Evidently, Puerto Ricans are a people who speak two languages, but not all Puerto Ricans speak two languates. What impact does the demographic fact of a Puerto Rican majority in the 50 states have on Puerto Rico and its political status options? What do these Puerto Rican demographics mean within the framework of massive changes in the demographic composition of the United States, where one of six inhabitants is, and soon one out of five will be Hispanic? There are now more than 60 million Hispanics in the United States (59,740,273 in the year 2018), which in economic terms means a Gross Domestic Product that is larger than that of the most populous Latin American countries (Brazil, Mexico). The increasing demographic weight of Latinos in the United States represents, potentially, a new political powerhouse capable of redefining the U.S. political system. What is the meaning of all these changes for Puerto Rico? We do not have the answers.

What is the significance of the fact that two thirds of Puerto Ricans now live outside Puerto Rico? Evidently, Puerto Ricans are a people who speak two languages, but not all Puerto Ricans speak two languates. What impact does the demographic fact of a Puerto Rican majority in the 50 states have on Puerto Rico and its political status options? What do these Puerto Rican demographics mean within the framework of massive changes in the demographic composition of the United States, where one of six inhabitants is, and soon one out of five will be Hispanic? There are now more than 60 million Hispanics in the United States (59,740,273 in the year 2018), which in economic terms means a Gross Domestic Product that is larger than that of the most populous Latin American countries (Brazil, Mexico). The increasing demographic weight of Latinos in the United States represents, potentially, a new political powerhouse capable of redefining the U.S. political system. What is the meaning of all these changes for Puerto Rico? We do not have the answers. For the moment, it is worth nevertheless to begin formulating the questions.

For the moment, it is worth nevertheless to begin formulating the questions. 61%

61% 52%

52% 70%

70% 06%

06% 14%

14% 15%

15% 94%

94% 65%

65% 54%

54% 59%

59% 51%

51% 55%

55% 96%

96%