Puerto rican tribal: What Became of the Taíno? | Travel

Puerto Rico Taino – Etsy.de

Etsy is no longer supporting older versions of your web browser in order to ensure that user data remains secure. Please update to the latest version.

Take full advantage of our site features by enabling JavaScript.

Find something memorable,

join a community doing good.

(1,000+ relevant results)

Taino Tribe | Tribalpedia

“If you look far enough beyond your adversities you will always find something to believe in; something to be proud of. ”~Taino Proverb~

”~Taino Proverb~

“The good spirit Yocahú Bagua Maracoti reigned on the sacred mountain of Yuké, protecting the land of Borikén (Puerto Rico) and the Greater Antilles.” -Taino Belief-

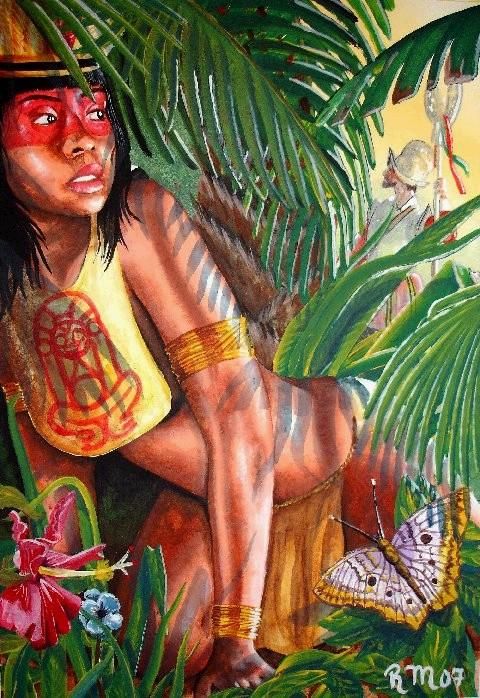

Taino woman.

Taino Dona Varin Cheverez, from the town Morovis in Puerto Rico.

Taino Flag image Antonio Martins

History

The Taínos were pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Bahamas, Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. It is thought that the seafaring Taínos are relatives of the Arawak people of South America. The Taíno language is a member of the Arawakan language family, which ranges from South America across the Caribbean. At the time of Columbus’s arrival in 1492, there were five Taíno chiefdoms and territories on Hispaniola (modern day Haiti and Dominican Republic), each led by a principal Cacique (chieftain), to whom tribute was paid.

Puerto Rico, also, was divided into chiefdoms. As the hereditary head chief of Taíno tribes, the cacique was paid significant tribute. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the largest Taíno population centers may have contained over 3,000 people each. The Taínos were historically enemies of the neighboring Carib tribes, another group with origins in South America who lived principally in the Lesser Antilles. The relationship between the two groups has been the subject of much study. For much of the 15th century, the Taíno tribe was being driven to the northeast in the Caribbean (out of what is now South America) because of raids by Caribs. Many Carib women spoke Taíno because of the large number of female Taíno captives among them. By the 18th century, Taíno society had been devastated by introduced diseases such as smallpox, as well as other problems like intermarriages and forced assimilation into the plantation economy that Spain imposed in its Caribbean colonies, with its subsequent importation of African slave workers.

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the largest Taíno population centers may have contained over 3,000 people each. The Taínos were historically enemies of the neighboring Carib tribes, another group with origins in South America who lived principally in the Lesser Antilles. The relationship between the two groups has been the subject of much study. For much of the 15th century, the Taíno tribe was being driven to the northeast in the Caribbean (out of what is now South America) because of raids by Caribs. Many Carib women spoke Taíno because of the large number of female Taíno captives among them. By the 18th century, Taíno society had been devastated by introduced diseases such as smallpox, as well as other problems like intermarriages and forced assimilation into the plantation economy that Spain imposed in its Caribbean colonies, with its subsequent importation of African slave workers.

The first recorded smallpox outbreak in Hispaniola occurred in December 1518 or January 1519. It is argued that there was substantial mestizaje (racial and cultural mixing) as well as several Indian pueblos that survived into the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico, did not bring women. They took Taíno women for their wives, which resulted in mestizo children.

It is argued that there was substantial mestizaje (racial and cultural mixing) as well as several Indian pueblos that survived into the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico, did not bring women. They took Taíno women for their wives, which resulted in mestizo children.

Culture Then

Taíno society was divided into two classes: naborias (commoners) and nitaínos (nobles). These were governed by chiefs known as caciques (who were either male or female), who were advised by priests/healers known as bohiques. Bohiques were extolled for their healing powers and ability to speak with gods and as a result, they granted Taínos permission to engage in important tasks. Taínos lived in a matrilineal society. When a male heir was not present the inheritance or succession would go to the eldest child (son or daughter) of the deceased’s sister.

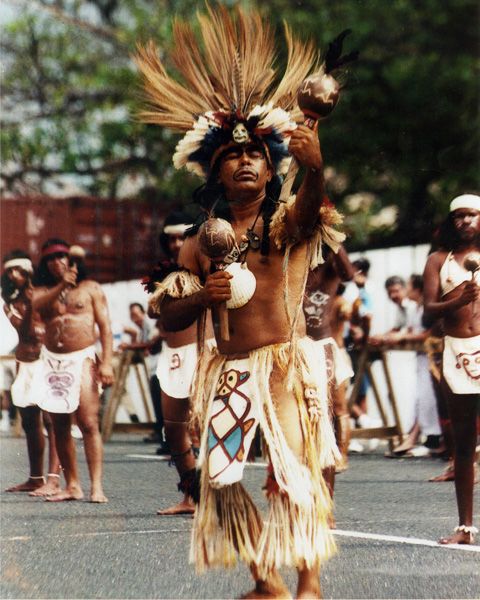

The Taínos had avunculocal post-marital residence meaning a newly married couple lived in the household of the maternal uncle. The Taínos were very experienced in agriculture and lived a mainly agrarian lifestyle but also fished and hunted. A frequently worn hair style featured bangs in front and longer hair in back. They sometimes wore gold jewelry, paint, and/or shells. Taíno men sometimes wore short skirts. Taíno women wore a similar garment (nagua) after marriage. Some Taíno practiced polygamy. Men, and sometimes women, might have two or three spouses, and it was noted that some caciques would even marry as many as 30 wives.

The Taínos were very experienced in agriculture and lived a mainly agrarian lifestyle but also fished and hunted. A frequently worn hair style featured bangs in front and longer hair in back. They sometimes wore gold jewelry, paint, and/or shells. Taíno men sometimes wore short skirts. Taíno women wore a similar garment (nagua) after marriage. Some Taíno practiced polygamy. Men, and sometimes women, might have two or three spouses, and it was noted that some caciques would even marry as many as 30 wives.

Taínos lived in metropolises called yucayeques, which varied in size depending on the location; those in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola being the largest and those in the Bahamas being the smallest. In the center of a typical village was a plaza used for various social activities such as games, festivals, religious rituals, and public ceremonies. These plazas had many shapes including oval, rectangular, or narrow and elongated. Ceremonies where the deeds of the ancestors were celebrated, called areitos, were performed here. Often, the general population lived in large circular buildings (bohios), constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. These houses would surround the central plaza and could hold 10-15 families. The cacique and his family would live in rectangular buildings (caney) of similar construction, with wooden porches. Taíno home furnishings included cotton hammocks (hamaca), mats made of palms, wooden chairs (dujo) with woven seats, platforms, and cradles for children.

Often, the general population lived in large circular buildings (bohios), constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. These houses would surround the central plaza and could hold 10-15 families. The cacique and his family would live in rectangular buildings (caney) of similar construction, with wooden porches. Taíno home furnishings included cotton hammocks (hamaca), mats made of palms, wooden chairs (dujo) with woven seats, platforms, and cradles for children.

Tainos Today

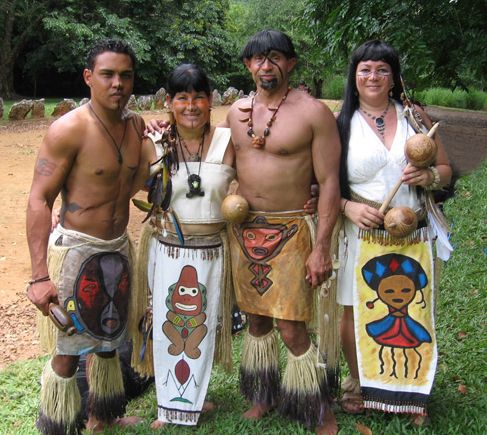

Descendants of Taino- Carib

Although some historians asserted that the Caribbean Taino-Arawak Indians were wholly extinct, victims of Spanish conquest, today, it is known that thousands of Taino descendants are alive and well, not only in Cuba but in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Florida, New York, California, Hawaii and even Spain. Frank Moya Pons, a Dominican historian documented that Spanish colonists intermarried with Taíno women, and, over time, these mestizo descendants intermarried with Africans, creating a tri-racial Creole culture.

Anthropologist and archaeologist Dr. Pedro J. Ferbel Azacarate writes that Taínos and Africans lived in isolated Maroon communities, evolving into a rural population with predominantly Taíno cultural influences. Ferbel documents that even contemporary rural Dominicans retain Taíno linguistic features, agricultural practices, foodways, medicine, fishing practices, technology, architecture, oral history, and religious views. “It’s surprising just how many Taino traditions, customs, and practices have been continued,” says David Cintron, who wrote his graduate thesis on the Taíno revitalization movement. “We simply take for granted that these are Puerto Rican or Cuban practices and never realize that they are Taino.”

A recent study conducted in Puerto Rico suggests that over 61% of the population possess Amerindian mtDNA Heritage groups, such as the Jatibonicu Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken, Puerto Rico (1970), the Taíno Nation of the Antilles (1993), the United Confederation of Taíno People (1998) and El Pueblo Guatu Ma-Cu A Boriken Puerto Rico (2000), have been established to foster Taíno culture.

Taino Myth: The Rainbow

The forest dwarfs had caught Yobuenahuaboshka in an ambush and cut off his head. The head bumped its way back to the land of the Cashinahuas. Although it had learned to jump and balance gracefully, nobody wanted a head without a body.

“Mother, brothers, countrymen,” it said with a sigh, “Why do you reject me? Why are you ashamed of me?” To stop the complaints and get rid of the head, the mother proposed that it should change itself into something, but the head refused to change into what already existed. The head thought, dreamed, figured. The moon didn’t exist. The rainbow didn’t exist. It asked for seven little balls of thread of all colors. It took aim and threw the balls into the sky one after the other. The balls got hooked up beyond the clouds; the threads gently unraveled toward the earth.

Before going up, the head warned: “Whoever doesn’t recognize me will be punished. When you see me up there, say: ‘There’s the high and handsome Yobuenahuaboshka!’” Then it plaited the seven hanging threads together and climbed up the rope to the sky.

That night a white gash appeared for the first time among the stars. A girl raised her eyes and asked in astonishment: “What’s that?” Immediately a red parrot swooped upon her, gave a sudden twirl, and pricked her between the legs with his sharp-pointed tail. The girl bled. From that moment, women bleed when the moon says so.

Next morning the cord of seven colors blazed in the sky. A man pointed his finger at it. “Look, look! How extraordinary!” He said it and fell down. And that was the first time that someone died.

Sources:

Puerto Rico Taino

El Boricua

Taino Flag

Wikipedia

Myth:

Memory of Fire: Genesis

Words /phrases from the Reading.

Maroon

Boriken

Mysteries of history. Rubric “Disappeared Civilizations”. People who met Columbus

These people gave humanity a hammock, cigars, canoes, dry cakes and some words that have passed into European languages. They had long black hair and copper skin; they smoked pipes and chewed tobacco, drank coffee from small fig cups, ate a lot of cassava, and wore linen slippers. We are talking about the Indians, united by the name “secretly.”

They had long black hair and copper skin; they smoked pipes and chewed tobacco, drank coffee from small fig cups, ate a lot of cassava, and wore linen slippers. We are talking about the Indians, united by the name “secretly.”

Secret – the collective name of the Indian tribes that once inhabited Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas and a number of the Lesser Antilles. It became widespread only in the 20th century. Before that, other ethnonyms were in use. For example, Europeans called the same ethnic group Arawaks, which means cassava flour (tapioca), which was the main food of these tribes.

A good peaceful person

In August 1492, three ships of Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain, crossed the Atlantic, and a couple of months later the exhausted crew saw a riot of tropical vegetation in the middle of the ocean. It was land – the island of San Salvador in the Bahamas. Since then, this day – October 12, 1492 – is considered the official date of the discovery of America.

The natives who inhabited the island warmly welcomed the Spanish sailors. They called themselves “secretly”, which meant “a good peaceful person” or “we are good”, in contrast, probably, with the “bad” Caribs – neighbors from the east and their traditional rivals. But the Europeans had no doubt that they had sailed to India, so they considered the locals to be Indians. In a letter to the King of Spain, Columbus wrote: “I saw how three of my people put a crowd of Indians to flight. They have no weapons, and they walk around naked… These people are friendly and not at all aggressive… They care about their neighbors and talk to each other quietly and peacefully with an unchanging smile on their faces.”

It is believed that it was the discoverer of America who called the secretly “Indians”, and this name eventually covered all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere. On this occasion, he wrote: “In all these islands, I did not notice a great variety either in the appearance of people, or in their customs and language. On the contrary, they all understand each other … ”Later, Columbus realized that this was not so. Acquaintance of Europeans with secretly occurred in stages as they colonized the Caribbean.

On the contrary, they all understand each other … ”Later, Columbus realized that this was not so. Acquaintance of Europeans with secretly occurred in stages as they colonized the Caribbean.

There is a point of view that the natives who inhabited the region before the arrival of the Spanish sailors descended from tribes that came from the tropical forests of Venezuela and from the banks of the Orinoco River. For a long time, travelers used various terms for their names. Today, historians, linguists and anthropologists believe that the term “Taino” should refer to all the Taino (Arawak) tribes, except for the Caribs. At the same time, most experts have come to the conclusion that there has never been a single Indian people or tribe under this name. However, no one denies the Taino civilization, which was the most developed in those places and which had a huge impact on the way of life and culture of neighboring tribes in the pre-Columbian period.

Conuco fruit

Secretly engaged in agriculture, as well as fishing and hunting. They cultivated their crops on the so-called “conuco” – large ridges, which were planted with various plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. With the help of primitive wooden hoes, the Indians grew maize (corn), squash, legumes, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts and other crops. Vegetables, as well as meat and fish, secretly formed the basis of nutrition. There was never a lot of big game on the islands, so any living creature was eaten: rats, bats, worms, turtles, ducks and other local “delicacies”.

They cultivated their crops on the so-called “conuco” – large ridges, which were planted with various plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. With the help of primitive wooden hoes, the Indians grew maize (corn), squash, legumes, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts and other crops. Vegetables, as well as meat and fish, secretly formed the basis of nutrition. There was never a lot of big game on the islands, so any living creature was eaten: rats, bats, worms, turtles, ducks and other local “delicacies”.

Secretly, cotton, hemp and palm trees were widely used to make fishing nets and ropes. Their canoes could carry from 2 to 150 people. The average canoe accommodated about 15-20 people. They secretly used bows and arrows and sometimes smeared the tips with various poisons. For fishing, they used harpoons, and for military purposes – wooden combat clubs.

An ordinary Indian village consisted of a flat area in the center, surrounded by large round huts built of wooden poles, woven straw mats and palm leaves. 10-15 families lived in each of them. From the furniture in the house there were cotton hammocks, palm mats, wooden chairs with wicker seats, platforms and baby cradles.

10-15 families lived in each of them. From the furniture in the house there were cotton hammocks, palm mats, wooden chairs with wicker seats, platforms and baby cradles.

The society secretly had a strict class hierarchy. It was divided into four main groups – ordinary people, junior leaders, clergy (they are also healers) and leaders (caciqs). There were also slaves – captured foreigners who did the hardest work. Kasiki, unlike ordinary tribesmen, lived in rectangular buildings with a wooden porch. Some tribes practiced polygamy, when a man could have 2 or 3 wives, and caciques – up to 30 wives. At the same time, there are cases when women had 2 or 3 husbands.

Secretly had a popular “trademark” hairstyle: bangs on the forehead and long hair on the back of the head. Often they wore gold items and decorated the body with colored paintings and shells. Their traditional clothing consisted of short “nava” – loincloths in the form of aprons, worn by both men and women after marriage.

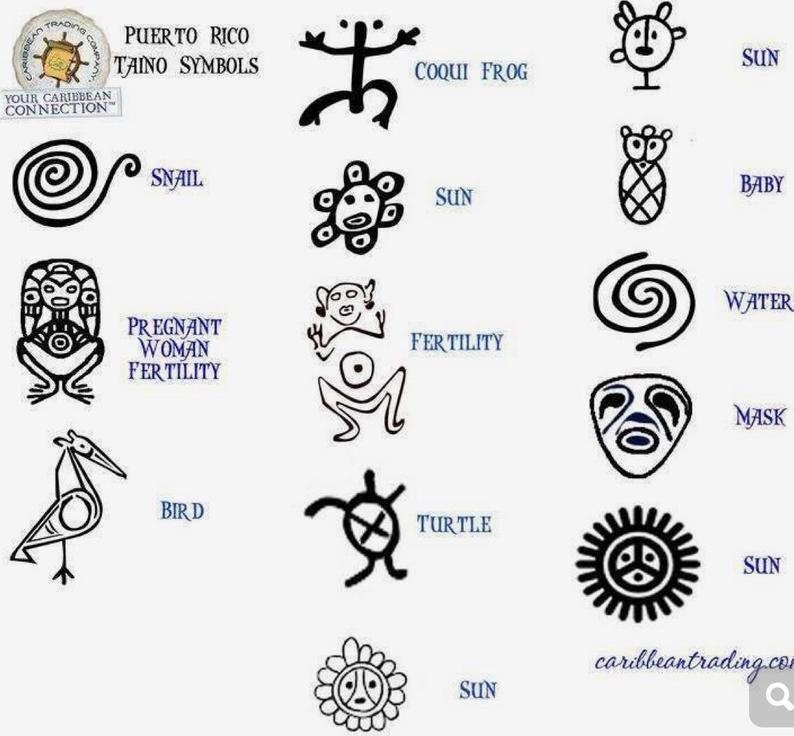

Secretly revered all forms of life and worshiped the ancestors and spirits, which were called “seven” or “zem”. Their images in the form of figurines and sculptures made of wood and stone, as well as special masks and amulets were supposed to protect people from misfortunes and illnesses. Many “seven” have survived in the form of toads, turtles, snakes, caimans, as well as various abstract and humanoid faces. Some of these include a small table or tray on which a special hallucinogenic mixture (“cohoba”) is believed to have been placed to be inhaled through the nose. During some rites, vomiting was secretly induced using a swallowing stick. This was done in order to cleanse the body of impurities – both literal physical and symbolic spiritual cleansing. However, all these rituals could not protect them from the colonialists.

Surviving ethnos

Throughout the 20th century, it was believed that everyone secretly died out in the 17th century. Scientists were sure that the Indians were mostly destroyed by the Spanish colonizers, and the surviving tribes could not survive the diseases introduced by Europeans and backbreaking work on plantations. The importation of a huge number of slaves from Africa into the Caribbean colonies also played a huge role. In Cuba, on the islands of Hispaniola (Haiti) and Puerto Rico, active miscegenation of the local population began. Not only Africans, but also Spaniards played their role in this process. They did not bring women with them and actively entered into civil marriage with graceful Tainos. This often led to conflicts. At 149In the year 3, the Indians even destroyed the Spanish fort Navidad (“Christmas”) based in Haiti and killed almost all of its defenders. As it turned out, this happened because the Spaniards committed violence against the natives.

Scientists were sure that the Indians were mostly destroyed by the Spanish colonizers, and the surviving tribes could not survive the diseases introduced by Europeans and backbreaking work on plantations. The importation of a huge number of slaves from Africa into the Caribbean colonies also played a huge role. In Cuba, on the islands of Hispaniola (Haiti) and Puerto Rico, active miscegenation of the local population began. Not only Africans, but also Spaniards played their role in this process. They did not bring women with them and actively entered into civil marriage with graceful Tainos. This often led to conflicts. At 149In the year 3, the Indians even destroyed the Spanish fort Navidad (“Christmas”) based in Haiti and killed almost all of its defenders. As it turned out, this happened because the Spaniards committed violence against the natives.

During his second journey, Columbus began to demand secret payment of tribute. Every Indian over the age of 14 had to give a certain amount of gold. Initially, for failure to comply with these requirements, the Indians were executed or, at best, mutilated for edification. Later, for fear of losing their labor force, they were forced to hand over 11 kilograms of cotton. Secretly worked for the colonists for most of the year, which did not allow them to develop their own economy.

Initially, for failure to comply with these requirements, the Indians were executed or, at best, mutilated for edification. Later, for fear of losing their labor force, they were forced to hand over 11 kilograms of cotton. Secretly worked for the colonists for most of the year, which did not allow them to develop their own economy.

The result was disastrous: the indigenous population practically disappeared. It seemed that only fantastic legends remained from him. For example, about a strange creature “higue” – an Indian dwarf who lived in the waters of rivers and lakes, who lured and led travelers astray. It surprisingly resembles gnomes from European legends. Or the myth of “cagueiros” – people who can turn into animals. From this world of ancient religion comes the famous Cuban spiritualism with its frightening rituals, which were mistakenly seen as having African roots.

Today it turns out that many people consider themselves direct descendants of the Taino, especially among Puerto Ricans. In addition, in Cuba, according to ethnographers, more than a thousand people have preserved elements of this culture. They mainly live in the mountains in the east of Cuba, in the hard-to-reach province of Guantanamo, where even the air is permeated with the “Indian spirit”. About the local customs, cuisine, crafts and even the appearance of local residents are secretly reminded of.

In addition, in Cuba, according to ethnographers, more than a thousand people have preserved elements of this culture. They mainly live in the mountains in the east of Cuba, in the hard-to-reach province of Guantanamo, where even the air is permeated with the “Indian spirit”. About the local customs, cuisine, crafts and even the appearance of local residents are secretly reminded of.

Evgeniy YAROVOY

Indians in the USA, tribes and families, features of life

The American Indian family has been studied in a wide and varied way over the centuries. However, this applies exclusively to its traditional forms or their remnants that existed in the so-called pre-reservation period. And one cannot help but regret that family relations among the indigenous population in the modern period were practically not analyzed. At present, with a huge number of sociological and demographic surveys of the family in the United States, as such, issues related to the Indian family are almost not covered. Of the works that most closely affect the problem of interest to us, we can single out the articles of the American scientists E. Warheftig and L. Ruffing, as well as the Soviet ethnographer S.V. Cheshko. Those materials about the modern family of Indians, which can still be extracted from American statistics, official documents and ethnographic works, are attracted by us to the maximum.

Of the works that most closely affect the problem of interest to us, we can single out the articles of the American scientists E. Warheftig and L. Ruffing, as well as the Soviet ethnographer S.V. Cheshko. Those materials about the modern family of Indians, which can still be extracted from American statistics, official documents and ethnographic works, are attracted by us to the maximum.

Contents

- 1. Indian family

- 2. Indian Marriages and Divorces USA

- 3. Number of children in families

- 4. Indians after World War II

- 5. Causes of the breakup of Indian families

- 6. Indians in the USA in the 80s

- 7. Benefits and material support for the elderly

Family of Indians

It is advisable to preface the article with the following comment. An Indian family, as defined by the US census, is a group of people who live together in a marriage relationship (registered or unregistered) or parent-child relationship. Along with this, the unit of the socio-demographic survey is also the household (household), i.e. a person or group of persons occupying a separate dwelling. Thus, a family can have at least two people, and a household can consist of a single person, a family in the generally accepted sense of this term, and, finally, of such associations in which close and distant relatives live, etc.

Along with this, the unit of the socio-demographic survey is also the household (household), i.e. a person or group of persons occupying a separate dwelling. Thus, a family can have at least two people, and a household can consist of a single person, a family in the generally accepted sense of this term, and, finally, of such associations in which close and distant relatives live, etc.

By the beginning of our century, the family had become the basis of the social organization of Native Americans, if not completely displacing, then at least sharply reducing the significance of the clan. The resettlement of Indians on reservations, which was generally completed by the 1980s, the introduction of private land ownership into communities by legislative procedure, breaking the traditional economic models of certain tribes, destroyed tribal groups as economic cells. Their place was taken by a family, or rather, a household. And although some remnants of the tribal organization among some Indian peoples were found to a certain extent until the beginning of the 60s of the XX century, the mentioned study by S. V. Czeshko convincingly showed that its functional role was symbolic.

V. Czeshko convincingly showed that its functional role was symbolic.

If we systematize the extremely fragmentary data available for the first decade of our century on Indian households, we will see that they usually consisted of an extended family, which at that time met in two typological variants. The first is a polygamous marriage. By 1910, about 490 such families were recorded among the American Indians; they were all polygynous. Basically, polygamous marriages were common among the Iawahs, who accounted for more than 90% of such unions. The main reason for the stability of polygamy among the Navajos is the persistence of the practice of inheriting livestock through the female line. To become the owner of a large herd, a man had to marry several women at the same time. However, already in those years, polygamy, according to an eyewitness agent of the Iawah reservation, was becoming an unpopular and outgoing form of marriage, remaining the lot of the older generation. Suffice it to say that among young Indians under the age of 30, only 80 people were in polygamous marriages at the beginning of the century; in general, polygamous families accounted for less than 2% of the total number of Indian families. In addition to the Navajos, isolated cases of polygamous marriages were noted among the Tetons, Apaches, Blackfoots, Kiowas and Northern Cheyennes.

In addition to the Navajos, isolated cases of polygamous marriages were noted among the Tetons, Apaches, Blackfoots, Kiowas and Northern Cheyennes.

The second dominant variant of the family union among the indigenous population of the United States in the first half of the 20th century. there was a married couple with several (usually three) generations of relatives. This type as a whole was similar to the all-American type of rural family, however, it had a number of characteristic features, which together constitute some specifics of the Indian family collective. First of all, it concerned its composition. Usually, in addition to parents and their unmarried children, an extended family of Indians included not only older married children who had their own offspring, but also other relatives of its head, including adopted ones. In conditions when agriculture was the basis of the livelihood of the indigenous inhabitants of the country and the entire burden of economic activity fell directly on the family collective, the undivided Indian family maintained considerable stability throughout the entire period until the Second World War. In this regard, the US census data are very characteristic.40, from which it is clear that in each registered Indian family, except for its core, an average of 3.8 relatives lived. Thus, the extended family remained a typical component of Indian social life longer than the rest of their fellow citizens.

In this regard, the US census data are very characteristic.40, from which it is clear that in each registered Indian family, except for its core, an average of 3.8 relatives lived. Thus, the extended family remained a typical component of Indian social life longer than the rest of their fellow citizens.

A certain originality distinguished the family of indigenous people in the sphere of marriage and family relations. In the pre-war period, the vestiges of tribal norms and ethnic traditions of the pre-reservation period were, perhaps, preserved to the greatest extent. For example, until the 1930s, among the Californian Maidu, there was a custom according to which young spouses, after marriage, were obliged to live with their wife’s parents for about six months. Their neighbors, the Yokuts, showed signs of tribal exogamy in the same years. The Indians of the Great Basin, especially the Shoshone, practiced cross-cousin marriage quite widely. The peoples of the Southwestern United States – the Hopi, the Pueblo – had a matrilineal kinship account and a matrilocal settlement. Similar phenomena were recorded in the 1940s among the Iowa Foxes.

Similar phenomena were recorded in the 1940s among the Iowa Foxes.

US Indians Marriage and Divorce

With regard to the average age of marriage, US Indians did not differ significantly from the rest of the country in this indicator. On the eve of World War II, it was about 20 years for women and 25 years for men. However, at the beginning of the XX century. some indigenous peoples sometimes nevertheless observed marriages concluded in childhood. “Although the Indians are no more immoral than other people,” documents of that time noted, “ugly things are practiced among them … the worst of which is the marriage of girls. A child aged 10-13 is sold to a 40-50-year-old man for a few pony heads. However, already at that time such phenomena were of a single nature: census 1910 revealed only 44 cases where a girl younger than 15 was married.

On the whole, marriage rates among Native Americans were at a high level. During the first half of the XX century. the proportion of married men over 18 years of age was 54%, and women, respectively, 60%. Marriages, as a rule, were registered with the agent of the corresponding reservation, much less often – in the church. True, at the beginning of the century, there were cases of evasion of many married couples from the official registration of their union. The reason was the need to pay legal formalities, which the Indians tried to avoid. But under pressure from the American authorities, the procedure for registering marriage under US law has become the norm for the indigenous population.

Marriages, as a rule, were registered with the agent of the corresponding reservation, much less often – in the church. True, at the beginning of the century, there were cases of evasion of many married couples from the official registration of their union. The reason was the need to pay legal formalities, which the Indians tried to avoid. But under pressure from the American authorities, the procedure for registering marriage under US law has become the norm for the indigenous population.

In terms of divorce, the situation in Indian families generally corresponded to the norms of a rural patriarchal society that cemented marriage due to economic necessity, which is partly confirmed by statistical data. At the beginning of the 20th century, among the inhabitants of the reservations, the proportion of people who were divorced did not exceed 0.5% for men and 0.7% for women. By 1940, however, it had increased to 1.4% and 1.9%, respectively. These more than favorable statistics, of course, could not reflect the actual breakup of families without an official divorce procedure. The likelihood of such cases, in our opinion, was quite high, given that the indigenous peoples at that time were relatively tolerant of pre- and extramarital sexual relations.

The likelihood of such cases, in our opinion, was quite high, given that the indigenous peoples at that time were relatively tolerant of pre- and extramarital sexual relations.

Number of children in families

In the first half of our century, Indian families were distinguished by a high level of children. Native American values stimulated motherhood. An Indian woman, married and unmarried, always wants to have a child, even if she does not have a penny to her name and she will be forced to swaddle him in rags. She is not ashamed of giving birth … which sometimes happens in front of other children, and they are aware of what happens to their mother when she is going to have another child, testified an American publicist who studied life in Indian communities in the late 20s years. As a result of these attitudes, Native American birth rates remained consistently high in the prewar period, with an average of four children per woman of childbearing age. The proportion of families with many children was also high: almost 40% of all family groups had more than five children each. If we add to them 45% of families with three or four children, then only 15% remained for the share of small children. In other words, the reproduction of the Indians was of a pronounced extended nature, and one would have expected a very rapid rate of natural growth of the Indian population, if not for the extremely high level of infant mortality associated with poor medical care for the inhabitants of the reservations and especially with insufficient obstetric care. The latter was usually carried out not by medical personnel in the clinic, but by older relatives at home, and the only tool used was scissors to cut the umbilical cord. And although among most Indian peoples, according to custom, the mother of a newborn was released for the first time from housework and she had the opportunity to devote herself to caring for the baby, unsanitary conditions and the prevalence of infections did their job. As a result, for the period from 1900 to 1940, the number of indigenous people increased only 1.

If we add to them 45% of families with three or four children, then only 15% remained for the share of small children. In other words, the reproduction of the Indians was of a pronounced extended nature, and one would have expected a very rapid rate of natural growth of the Indian population, if not for the extremely high level of infant mortality associated with poor medical care for the inhabitants of the reservations and especially with insufficient obstetric care. The latter was usually carried out not by medical personnel in the clinic, but by older relatives at home, and the only tool used was scissors to cut the umbilical cord. And although among most Indian peoples, according to custom, the mother of a newborn was released for the first time from housework and she had the opportunity to devote herself to caring for the baby, unsanitary conditions and the prevalence of infections did their job. As a result, for the period from 1900 to 1940, the number of indigenous people increased only 1. 2 times – from 265 to 333 thousand people.

2 times – from 265 to 333 thousand people.

Indians after the Second World War

Family relationships and families among the Indians of the United States after the Second World War have undergone significant changes due to the entire course of the socio-political development of the country and the integration of the indigenous population into the American economy. This was especially evident from the 1960s, when a rapid outflow of Indians from agriculture to other branches of production and the associated rapid increase in the proportion of urban residents began. Suffice it to recall the following: if by the beginning of the 60s more than 33% of Native Americans were employed in agriculture, and no more than 26% of them lived in cities, then in the 70s, respectively, 2 and 50%. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the circumstances mentioned led to a change in the social composition of the Indian population, which turned from predominantly small rural owners into hired workers. At 19In the 1980s, more than 80% of the natives of the United States were employed, while less than 35% two decades earlier.

At 19In the 1980s, more than 80% of the natives of the United States were employed, while less than 35% two decades earlier.

The most important problem of the existence of the modern Indian family is its stability as a special social institution. Statistics show that the situation among Native Americans is quite stable in this regard: in the 60s, families formed over 80% of officially registered Indian households, in the 70s – 82 and in the 80s – more than 77%. These indicators, which are noticeably higher than the national ones, are primarily associated with the very high marriage rate of Indians: in the 1980s, more than 49 people were married.% of Indian women over the age of 18 and almost 50% of men. However, the average marriage data varies depending on the age of the individuals. In the age group of 18-25 years, the number of women who entered into marriage is 1.5 times more than men, which is explained by the slightly higher average marriage age of the latter. In the groups of 26-35 and 36-45 years, the marriage rates for both sexes are almost the same. After the age of 45, the proportion of women who are married begins to gradually exceed the similar proportion of men, and in the group over 65 years of age quite significantly – 1.5 times. This is due to the lower average life expectancy of the stronger sex and, as a result, a rather large number (about 44 thousand) of widowed Indian women, whose share among adult women is almost 10%.

After the age of 45, the proportion of women who are married begins to gradually exceed the similar proportion of men, and in the group over 65 years of age quite significantly – 1.5 times. This is due to the lower average life expectancy of the stronger sex and, as a result, a rather large number (about 44 thousand) of widowed Indian women, whose share among adult women is almost 10%.

The decline in the prestige of family and marriage that has affected the United States of America in the past decades has affected, albeit to a lesser extent, Native Americans. In the early 1960s, the proportion of persons of each sex among the Indians who were married was higher than in the early 80s – 55 and 61%, respectively.

Divorces, the number of which is gradually increasing, should be singled out among the factors that undermine the stability of the family. In 1960, the divorce rate among indigenous people was 4.7% for men and 5.2% for women. K 1970, these figures increased to 6. 3 and 9.3%, and by 1980 they reached 10.5 and 14.1%. Of course they are lower; than the rest of the inhabitants of the United States, but the trend towards an increase in the number of broken marriages among the Indian population cannot be denied. But the more serious problem here, in our opinion, is the sharp increase in the number of legally unregistered divorces among acts of this kind. If in the 60s such cases were isolated, in the 80s they accounted for almost 1/3 of all divorces, and the number of women abandoned by their husbands exceeds that of men by 2.4 times.

3 and 9.3%, and by 1980 they reached 10.5 and 14.1%. Of course they are lower; than the rest of the inhabitants of the United States, but the trend towards an increase in the number of broken marriages among the Indian population cannot be denied. But the more serious problem here, in our opinion, is the sharp increase in the number of legally unregistered divorces among acts of this kind. If in the 60s such cases were isolated, in the 80s they accounted for almost 1/3 of all divorces, and the number of women abandoned by their husbands exceeds that of men by 2.4 times.

Reasons for the breakup of Indian families

The reasons for the breakup of Indian families are varied. Here is the dissatisfaction of the spouses with their life together, and the gap between the hopes placed on marriage and their real embodiment – in a word, everything that can destroy any family. However, as the American media emphasize, the main role in the collapse of Native American families is played by socio-economic factors: poor housing conditions and, in many cases, an elementary lack of means of subsistence, which very often acts as the root cause of family conflicts and an insurmountable obstacle to further living together. spouses. Thus, in modern conditions, the US Indian family as a whole shows rather great stability, however, the negative factors listed above, which resulted in numerous divorces, lead to a slow but steady increase in the proportion of people living outside the family: in the 70s it was 18 %, and in the 80s – already 23%, i.e., in other words, according to the latest data, 212 thousand Indians and 190 thousand Indian women.

spouses. Thus, in modern conditions, the US Indian family as a whole shows rather great stability, however, the negative factors listed above, which resulted in numerous divorces, lead to a slow but steady increase in the proportion of people living outside the family: in the 70s it was 18 %, and in the 80s – already 23%, i.e., in other words, according to the latest data, 212 thousand Indians and 190 thousand Indian women.

In terms of structure, the Indian family in the post-war period evolved from an undivided multigenerational family to a small nuclear family consisting of parents and their unmarried children. In the early 1960s, the bulk of Native Americans, especially on reservations, mostly in rural areas, lived in large families with a complex interweaving of vertical, or paternal, and horizontal, or fraternal, ties. A clear example of the existence of such kindred groups is the following description of a typical family for that time on the Pine Ridge Reservation (South Dakota). “Not far from Wounded Knee lives an ordinary family – an elderly husband and wife, their two married adult children and six grandchildren … sun with an awning stretched over pine poles. The summer house was a common kitchen, but in hot weather they slept there. Married children, however, lived separately in houses made of planks nearby. However, one should not think that such extended families were characteristic only of Indian communities in rural areas. The American media noted that many large Indian families lived in the cities as well.

“Not far from Wounded Knee lives an ordinary family – an elderly husband and wife, their two married adult children and six grandchildren … sun with an awning stretched over pine poles. The summer house was a common kitchen, but in hot weather they slept there. Married children, however, lived separately in houses made of planks nearby. However, one should not think that such extended families were characteristic only of Indian communities in rural areas. The American media noted that many large Indian families lived in the cities as well.

The 1960 census recorded the retention of large families among Indians in various parts of the country. As is clear from the data contained in it, an Indian family could include, in addition to parents and their unmarried younger children, also married older children with offspring. In such a family, as in the pre-war period, there lived indirect relatives of its head – by blood, by marriage, and even by adoptive members. The national average for every Indian household at that time was 3. 5 such persons, and in rural areas there were more of them than in cities – respectively 3.6 versus 3.4 people. Another indirect confirmation of the fact of the existence of large kindred groups is a comparison of data on the quantitative composition of Native American families. Although the average Indian family at that time consisted of 4.5 people, more than 26% of families in rural areas consisted of 5-6 people, and almost 27% of 7 or more (in the city, the share of such groups was 23 and 16%).

5 such persons, and in rural areas there were more of them than in cities – respectively 3.6 versus 3.4 people. Another indirect confirmation of the fact of the existence of large kindred groups is a comparison of data on the quantitative composition of Native American families. Although the average Indian family at that time consisted of 4.5 people, more than 26% of families in rural areas consisted of 5-6 people, and almost 27% of 7 or more (in the city, the share of such groups was 23 and 16%).

The main reasons for the stability of extended family groups were related to the sphere of the economy. In the 60s, production activities in the agricultural sector of the economy fell mainly on the rural family of the indigenous people. In conditions of low mechanization, every pair of hands, including the elderly and teenagers, counted. However, as the Indian population urbanized and entered the wage labor market, the economic side of family life changed. The productive activity of its members went beyond the family framework, and in everyday life the Indian family became a predominantly consuming unit, whose economic activity was limited mainly to the house.

More details about the economic functions of the family will be discussed below. Here we emphasize that the above-mentioned processes have accelerated the withering away of the undivided family as a special socio-economic organism and the isolation of small nuclear collectives from it. In the 70s, according to the observations of American ethnographers, large families among the Indians, although still quite common, remained mainly on reservations. The same is true of the statistics. The average size of a Native American family has hardly decreased since the 1960s, amounting to 4.4 people. The share of large family groups in rural areas remained close to the previous level: families of 5-6 people made up 24% there, and 26% of 7 or more people. However, in the cities their number visibly decreased, reaching 21 and 10%, respectively. In the composition of a large family, the main changes were manifested in a reduction in the number of indirect relatives of its head living with him. In the 70s, there were no more than 2.7 such persons on average per household, and in cities this figure was 2 people, while in rural areas – 3.2.

In the 70s, there were no more than 2.7 such persons on average per household, and in cities this figure was 2 people, while in rural areas – 3.2.

In the past decade, despite the fragmentation of the data, in our opinion, we can say that the multigenerational undivided families of Indians have practically sunk into the past. The number of members of an Indian family in the 80s averaged only 3.8 people, and the number of relatives of its head living in one household, even on reservations, was only 0.5 people. In cities, this figure is even lower – 0.3. It is interesting to note that in the few surviving large-family groups, vertical ties have practically disintegrated: only in 6% of families of this type, adult, married children lived with their parents. The rest of the households were fraternal multilineage groups of siblings and cousins with spouses and offspring. All this suggests that the small nuclear family has become the dominant form of family ties.

Thus, in the post-war period, the withering away of undivided large families took place gradually, and the difference in the rate of their disintegration was associated primarily with the socio-economic development of the Indian peoples. Therefore, extended family groups were better preserved in rural areas than in urban areas; where their production functions were more significant. As for the cultural and historical traditions of the indigenous people in the family sphere, we find the opinion of S.V. Cheshko, who considers their role in the conservation of extended families in the modern period insignificant. In other words, the almost complete completion of this process by now is a consequence of the Indians’ transition to subsistence through wage labor.

Therefore, extended family groups were better preserved in rural areas than in urban areas; where their production functions were more significant. As for the cultural and historical traditions of the indigenous people in the family sphere, we find the opinion of S.V. Cheshko, who considers their role in the conservation of extended families in the modern period insignificant. In other words, the almost complete completion of this process by now is a consequence of the Indians’ transition to subsistence through wage labor.

Indians in the USA in the 1980s

So, by the 1980s, the family of indigenous people in the USA had become two-generation and small in number. But as it separated from the extended kindred collective, the small family fell under the influence of various negative socioeconomic factors (unemployment, high cost of living, housing problem, etc.). Lacking the cementing foundation that its members once had in common, the nuclear family, in turn, began to suffer destruction, manifested in a constant, albeit slow by American standards, increase in the number of divorces, both formal and informal. The consequence of this was a steady increase in the number and proportion of incomplete families, mostly matrifocal, i.e. consisting of a mother and her minor children. If in the 60s the Indians had 9 such familiesthousand and they accounted for less than 14% of their total number, then in the 70s there were already 17.9 thousand (18.3%). In the 1980s, the number of incomplete families reached 50.2 thousand, and the share was 25%, i.e. almost one in four Indian families consisted of a mother and children, and thus about 107,000 young Native Americans grew up without a father. Incidentally, the prevalence of matrifocal families is also indirect evidence of the extinction of the historical traditions of Indian tribes that ensured the normal existence of a family without a breadwinner, for example, the custom of levirate or the custom of a brother settling with the family of a widowed sister, etc.

The consequence of this was a steady increase in the number and proportion of incomplete families, mostly matrifocal, i.e. consisting of a mother and her minor children. If in the 60s the Indians had 9 such familiesthousand and they accounted for less than 14% of their total number, then in the 70s there were already 17.9 thousand (18.3%). In the 1980s, the number of incomplete families reached 50.2 thousand, and the share was 25%, i.e. almost one in four Indian families consisted of a mother and children, and thus about 107,000 young Native Americans grew up without a father. Incidentally, the prevalence of matrifocal families is also indirect evidence of the extinction of the historical traditions of Indian tribes that ensured the normal existence of a family without a breadwinner, for example, the custom of levirate or the custom of a brother settling with the family of a widowed sister, etc.

The evolution of the type of Indian family from large to small has led to a change in the roles of its members, mainly the elderly and advanced ages. Representatives of these age categories, whose leading position in the system of relationships of a large family was previously determined by its way of life and reinforced by behavioral norms, literally had no place in a nuclear family with a different social climate (especially in cities). Elderly people, emphasized, in particular, in a statement of the Indian Council for the Elderly in Los Angeles, are in a state of severe moral crisis. On the one hand, it is generated by material reasons: the transformation from a family breadwinner into a dependent is perceived by many Indians as extremely painful. On the other hand, this circumstance is exacerbated by sociocultural factors. Separated from their communities, in which their respected position was sanctified by tradition and … emphasized by the kinship system, having lost their social function – the transmission of the cultural values of their tribe to the youth, the elderly urban Indians … lost their indisputable authority in the eyes of their young relatives .

Representatives of these age categories, whose leading position in the system of relationships of a large family was previously determined by its way of life and reinforced by behavioral norms, literally had no place in a nuclear family with a different social climate (especially in cities). Elderly people, emphasized, in particular, in a statement of the Indian Council for the Elderly in Los Angeles, are in a state of severe moral crisis. On the one hand, it is generated by material reasons: the transformation from a family breadwinner into a dependent is perceived by many Indians as extremely painful. On the other hand, this circumstance is exacerbated by sociocultural factors. Separated from their communities, in which their respected position was sanctified by tradition and … emphasized by the kinship system, having lost their social function – the transmission of the cultural values of their tribe to the youth, the elderly urban Indians … lost their indisputable authority in the eyes of their young relatives . .. which further increased the burden of old age ”, — noted later in the mentioned document.

.. which further increased the burden of old age ”, — noted later in the mentioned document.

Benefits and material support for the elderly

Naturally, the moral situation in Indian communities is much better than in cities, but the problem of older people on reservations is no less acute. Here, the issues of material support for the elderly came to the fore. Only 6% of older Indians were able to provide themselves with feasible work for hire. There is practically no opportunity for them to receive state benefits. Acting in the United States since 1965, the law on assistance to the elderly, until recently, did not apply to Indians in general. After entering it at 19In 1978, a corresponding amendment began to allocate $ 6 million for assistance and assistance to residents of elderly reservations, but this allowed only 16,000 Native Americans to be covered by benefits. Since communities are also generally unable to provide assistance programs for the elderly, care for them falls entirely on the young members of the family. And although it must be noted to the credit of the youth that the vast majority of them do everything possible for this, young people themselves have too little means to properly help their elderly relatives, the documents of some Indian communities emphasized.

And although it must be noted to the credit of the youth that the vast majority of them do everything possible for this, young people themselves have too little means to properly help their elderly relatives, the documents of some Indian communities emphasized.

Another side of the role changes in the Indian family was the gradual transformation of married women from housewives to hired workers. The need for this was dictated by the economic needs of a small family, whose material well-being was sometimes impossible to maintain without connecting the mother of the family to the labor market. The growth in the employment of married women has been quite rapid. In the 60s, only 7.8% of Jewish women worked in the public sector (in cities, their proportion was slightly higher than in reservations: 9.6 versus 7.1%), in the 70s this figure increased almost 5 times, reaching 34% (in cities – 39, in reservations – 28%). By the 1980s, the share of married women working for hire was already 41%.