Spain monetary system: Currency in Spain. Where to exchange money and how to pay

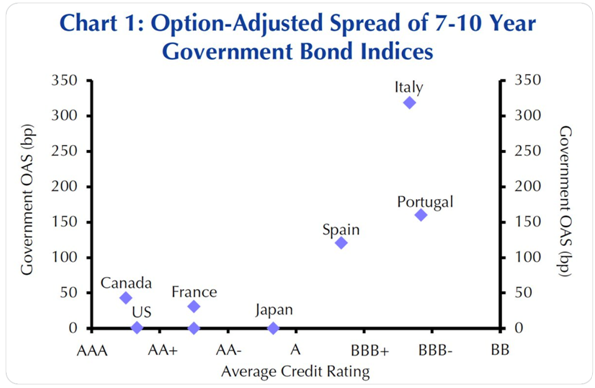

Spain – Global Financial Data

Back to All Currency

- Download PDF

Ferdinand and Isabella removed the last Moorish stronghold from Spain in 1492. Joseph Napoleon, the brother of Napoleon I, was made King of Spain from June 6, 1808 until December 11, 1813 when the Borbón dynasty was restored. Despite attempts to establish a Republic in 1873 and again in 1931, the country remains the Kingdom of Spain. Ceuta and Melilla are two Spanish possessions on the coast of Africa.

Silver coins minted in Sicily, Italy and France were circulating in Spain as early as the fifth century BC and cons were minted in Spain by 350 BC. The Visigoths issued coins until the Arab invasion of Spain in 711-712. During the Islamic period, copper fals, silver dirhems and gold dinars were minted in Spain.

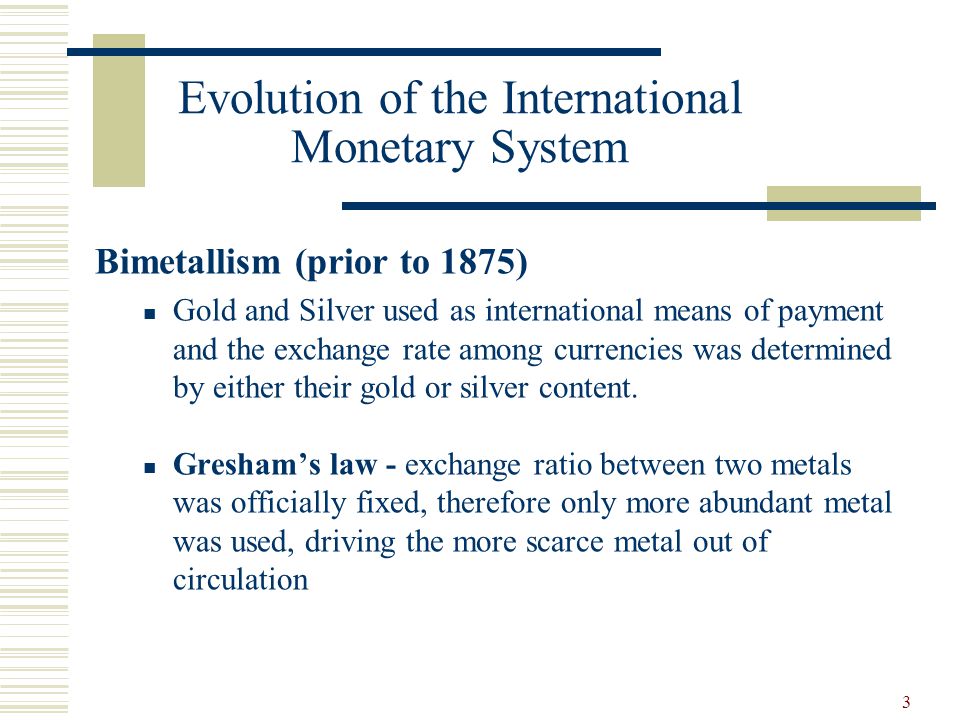

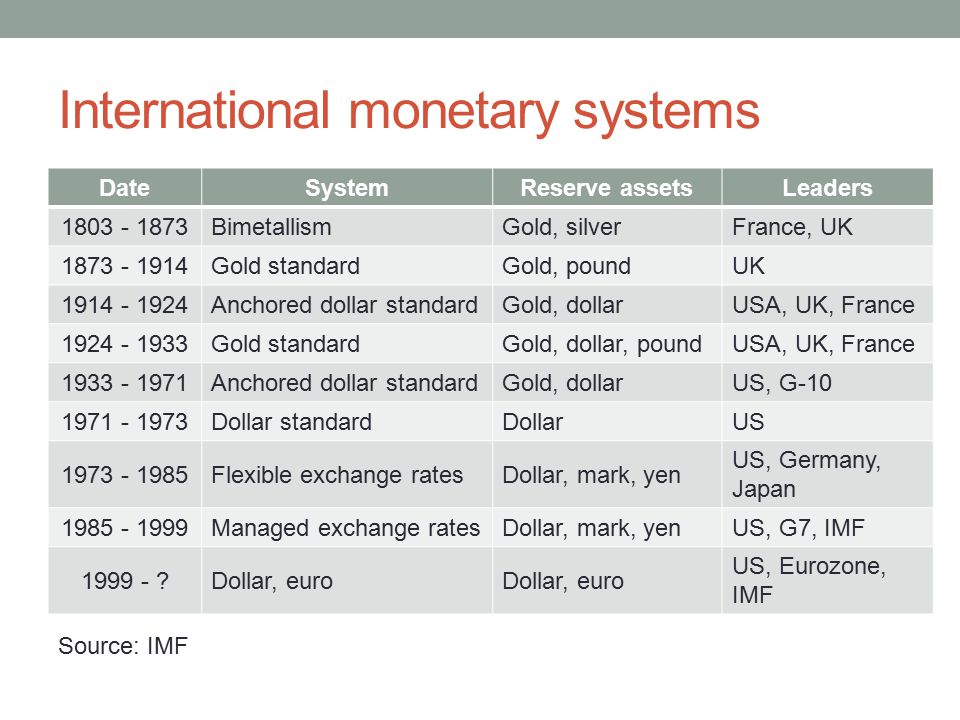

Spain had several different monetary systems that coexisted in different parts of Spain before the unification of the Spanish monetary system using the Peseta. All were units of account that had specie money that tried to reflect the monetary divisions inherent in each system. In 1391, Spain had to endure the simultaneous circulation of 132 types of coins. This led to monetary reforms in 1391, 1471, 1497, 1537, 1542, 1686, 1772, 1847, 1859, and of course 1999. Anyone who longs for the days when money was made out of gold, silver and copper, rather than paper, never lived during those days of monetary chaos. Probably, not even moneychangers could keep track of the different systems.

In 1391, Spain had to endure the simultaneous circulation of 132 types of coins. This led to monetary reforms in 1391, 1471, 1497, 1537, 1542, 1686, 1772, 1847, 1859, and of course 1999. Anyone who longs for the days when money was made out of gold, silver and copper, rather than paper, never lived during those days of monetary chaos. Probably, not even moneychangers could keep track of the different systems.

After Spain was united in 1492, the real, equal to 34 maravedis, was the principal unit of account. Charles V adopted the Ducado/Ducat (XESD) in 1537 with 1 Gold Ducado equal to .833 Pesos or 375 Maravedis. The Escudo (XESE) was introduced with the monetary reform of October 14, 1686 when the Real de Vellon was also introduced with one Piece of Eight (Piastre/Escudo) equal to 20 Reales de Vellon and 10 Reales de Vellon in 1737. The Escudo was divisible into 2 Pesos, 16 Reales or 544 Maravedis. The Escudo and its divisions were the principle coins used in Spain and especially in Spanish America.

The Decree of Aranjuez on May 29, 1772 tried to unify the monetary systems in Spain. The principle system was based upon the Piastre/Peso (XESP), equal to 10 Reales de Plata (silver), 20 Reales de Vellon (Billon of silver and copper), 340 Maravedis de Plata, and 680 Maravedis de Vellon. In Alicante, Catalonia, Mallorca and Valencia, a system based upon the Pound (XESL) was used with 1 Libra equal to 10 Reales, 20 Sueldos (Sous/Shillings), and 240 Dineros (Deniers/Pence). There were further subdivisions into 480 Mallas in Catalonia and 320 Dineros in Aragon. In Malaga, a Real (XESR) equal to 8.5 Quartos, 17 Ochavos, 34 Maravedis, 64 Blancos, 136 Cornados or 340 Dineros was used. In Navarre, the Ducado (XESD) was used with 1 Ducado equal to 49 Tarjas, 196 Ochavos, 392 Maravedis or 784 Cornados. Finally, the Spanish Doubloon (XESD) was used as a trade coin, so called because it was equal to two Escudos. In general 1 Quadruple (equal to a French Livre) was divisible into 4 Doubloons (Pistoles), 8 Escudos, 16 Reales, 80 Pesetas or 320 Reales. Finally, French Ecus (FRT) of 3 Livres Tournois were used in the northern part of Spain until 1821 when they were demonetized.

Finally, French Ecus (FRT) of 3 Livres Tournois were used in the northern part of Spain until 1821 when they were demonetized.

The Decree of Aranjuez hardly succeeded in bringing clarity to the Spanish Monetary system, so on May 31, 1847, Isabella II initiated her monetary reform, introducing the silver Real as the basis for the new system, with 1 gold Doubloon divisible into 5 silver Duros, 10 silver Escudos, 25 Pesetas, 100 Reales or 1000 Decimos de Real. Until 1847, the Spanish currency was quoted in terms of the Peso de la Plata Antigua, which was equal to 64/85 Peso Duros.

The Spanish Law of June 26, 1864 made the Escudo the monetary unit of all Spanish colonies with 1 Gold Doubloon equal to 10 Escudos equal to 100 Silver Reales. The Spanish monetary system was linked to the French monetary system with the introduction of the Peseta, made of equal weight to the Franc Germinal and with 1 Peso Duro = 5 Pesetas = 20 Reales. Spain joined the Latin Monetary Union on October 19, 1868 and simultaneously introduced the peseta, divisible into 100 Centimos, though the silver Spanish Peseta was slightly heavier than the French Franc. A number of private banks issued banknotes in Escudos or Reales de Vellon until l874 when the Banco de Espana obtained a monopoly on note issue and began issuing banknotes in Pesetas. Although the Latin Monetary Union began moving toward a gold standard in 1878, Spain stopped issuing gold coins in 1883.

A number of private banks issued banknotes in Escudos or Reales de Vellon until l874 when the Banco de Espana obtained a monopoly on note issue and began issuing banknotes in Pesetas. Although the Latin Monetary Union began moving toward a gold standard in 1878, Spain stopped issuing gold coins in 1883.

During the Spanish Civil War, the Nationalist Peseta (ESN) was issued by the Banco de Espana in Burgos beginning on November 13, 1936 and existed independently of the Republican Peseta issued from Madrid. After the defeat of the Republican forces on April 1, 1939, the Banco de Espana in Madrid began issuing Pesetas for all of Spain. Republican Peseta banknotes were repudiated on March 13, 1942. Spain also had two special Account Pesetas (ESA and ESB).

Spain adopted the Euro as its currency on January 1, 1999 with 1 Euro equal to 166.386 Spanish Pesetas. Euro banknotes and coins, issued by the European Central Bank began circulating on January 1, 2002, and the Spanish Peseta ceased to be legal tender on February 28, 2002. The Euro is divisible into 100 Cents.

The Euro is divisible into 100 Cents.

Back to All Currency

REQUEST A DEMO with a GFDFinaeon Specialist

History of the Peseta – FNMT

Introduction

With the minting of what was the last 100 Peseta coin on June 19, 2001 the issue of the peseta was finalized and the plates and dies became museum pieces for the reminiscence of future generations. Subsequently, on March 1, 2002, the Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre – Spanish Royal Mint (FNMT-RCM) inaugurated a new period in its history of minting, making it possible for Spanish citizens to live on a daily basis with the Euro.

Fitting Tribute

The farewell given to the peseta was set in motion with the minting of two coins: one, the coin most widely used on a daily basis, the 100 peseta coin, and the other the traditional silver commemorative, that of 2000 pesetas. Both reproduce the image of Hispania that was depicted on the first issue of pesetas in 1869.

A final farewell, a lasting tribute that the Ministry of the Economy, the General Directorate of the Treasury, the Bank of Spain and the Spanish Royal Mint itself wished to offer, in such a way as to put the last Spanish monetary unit within reach of all. It consists of a unique edition constituting of a piece of history that is available through the FNMT-RCM.

History: Learn more

The life of a coin is linked to the history of its country and to the events during the time of its circulation. The peseta, the last circulating coinage in Spain before the European single monetary system was implemented, came into being in 1868 during the reign of Isabel II. It was in circulation for over a hundred years during which time it became steeped in Spanish history.

You are invited to get to know the entire history (only Spanish version). Also, go by the Casa de la Moneda Museum!, where you will be able to trace Spain’s history as reflected in its coinage.

Coins

Every coin brings along with itself a small and particular piece of history. Coins have been exceptional witnesses, means of expression, vehicles of ideologies of each one of the episodes that form the history of a country, constituting a valuable and priced treasure, of much greater value than the motif stamped on the reverse.

Year created

On October 19, 1868, the peseta came into being as the monetary unit by virtue of a decree passed by the Provisional Government after Isabel II was overthrown. This Government decided to centralize the entire currency production in the old Madrid Mint, the beginning of what is today the FNMT-RCM. Since then the Fábrica has minted each and every one of the peseta coins that have circulated up until the advent of the Euro.

Each peseta encloses within its tiny proportions the history, the politics, the religion, the economy and the art of the instant in which it was minted. The peseta houses 134 years of concentrated Spanish history.

The peseta houses 134 years of concentrated Spanish history.

Name

The choosing of the name was mainly due to its familiarity of use. Some denominations such as “maravedi”, “real”, “escudo”, etc. got buried under the term peseta, commonly used during the reign of Isabel II. It also seems that in Catalonia pesetas had circulated since before the War of Independence.

First coins

On one side

The first coin minted in 1869 was the unit. It came into being bearing the legend “Gobierno Provisional” on the obverse, instead of “Spain”, which text would show on the subsequent mintings and on the silver coins. The motif chosen was the personification of Hispania resting on the Pyrennees inspired by the coins of the Emperor Hadrian. The bronze coin, on the other hand, represented Spain as a matronly figure sitting on the rocks. Both were magnificently engraved by Luis Marchionni, who, from 1861 held the position of principal engraver to the Casa de la Moneda (the Royal Madrid Mint).

And on the other

The reverse of the silver coin bore the Spanish coat-of-arms. The bronze portrayed the figure of a rampant lion holding aloft this coat-of-arms. This image gave rise to the popular denomination of “perra gorda” (ten-centime piece) or “perra chica” (five-centime piece), since people saw a dog where there was supposed to be a lion. After an international competition, three different sketches were extracted that served as inspiration for the definitive model by Luis Marchionni.

Iconography

Throughout the lifetime of the peseta as a monetary system, the design has evolved marked by the impressions of each moment and in very different directions.

From the start

In accordance with what was established in 1869 the Spanish national coat-of-arms is kept for the reverse, modifications being added over time. On the obverses the presence of Hispania was replaced by the royal effigy.

The Second Republic marked a break in the typology, as motifs were introduced of a republican inspiration in keeping with the status of the new government. On occasions the models were issued in a poorly finished condition due to the pressing need to get them minted.

On occasions the models were issued in a poorly finished condition due to the pressing need to get them minted.

The coming to power of General Franco involved a turning point in this respect, with the introduction of a portrait modeled in 1947 by Benlliure and adapted by Manuel Marín. The portrait of the mature Franco is by Juan de Avalos.

To the present day

Under the democracy the sizes and values were adhered to while bringing in the likeness of King Juan Carlos I in addition to the Royal Coat-of-arms. However, since 1990 the types were renovated every year in the pursuit of a commemorative intention that put an end to the exclusively monarchical tradition and gave way to cultural, artistic or local motifs.

Values

The fourteen values originally anticipated would not materialize until the reign of Alfonso XIII, when the precious metals were replaced by new metals and alloys, causing the loss of parity between the intrinsic and the nominal values. Even so, the mintings in gold were maintained until 1904 and those in silver to 1933. The latter gave way to the yellow Peseta made of brass and popularly known as “la rubia” (the blonde one). From that moment on the mintings have been based on copper, aluminum and nickel, and the designs have combined all kinds of alloys and sizes.

Even so, the mintings in gold were maintained until 1904 and those in silver to 1933. The latter gave way to the yellow Peseta made of brass and popularly known as “la rubia” (the blonde one). From that moment on the mintings have been based on copper, aluminum and nickel, and the designs have combined all kinds of alloys and sizes.

In parallel, and for purely economic reasons that add interest for collectors, collector coins continue to be minted in previous metals. The symbolic act of the last minting of the 100-peseta coin constitutes the end of the history of the peseta, its comings and goings, the heads and the tails of the beloved coin.

Last issue

- 1 peseta

- 5 pesetas

- 10 pesetas

- 25 pesetas

- 50 pesetas

- 100 pesetas

- 200 pesetas

- 500 pesetas

Banknotes

History in stamping

The arrival of the Euro put an end to part of the history of paper money, the era of the peseta, centuries of legend written and stamped on the banknotes throughout innumerable chapters in the history of Spain.

First issue

The first issue of paper money in pesetas was made in July 1874 coinciding with the concession granted to the Bank of Spain for the sole right to issue banknotes. Once this first step had been taken, the volume of banknotes would grow unceasingly as a reflection of the economic growth of the country. Except for the Civil War period, marked by problems of shortages and the emergence of every kind of means of payment, banknote issues have kept up a steady growth rate in keeping with the economy of the country. The banknote has come to form part of the daily life of Spain’s general public, and is looked upon as a mark of national identity.

Manufacturers

The first issue, printed by the FNMT-RCM, was on October 21, 1940. Until that time the workshops of the Bank of Spain and different British, American and German companies had been entrusted with the manufacture of Spain’s paper money.

Since 1941 the FNMT-RCM has exercised its sole right to manufacture Spanish paper currency. Since January 2002 the future of the FNMT-RCM is taking shape within a framework of close collaboration between the corporation and the European Central Bank in addition to other European manufacturers.

Since January 2002 the future of the FNMT-RCM is taking shape within a framework of close collaboration between the corporation and the European Central Bank in addition to other European manufacturers.

Technique and security

Historically, intaglio printing has been the most difficult to forge. This technique is used to print the main vignette and the ornamental borders. The remaining parts of the banknote are letterpress and offset printed. The methods used for reproducing the original engraving have been perfected over the years, but the figure of the engraver continues to be crucial.

Other elements such as the watermark, inks, fibres, threads and filaments are added to reinforce the security of the banknote.

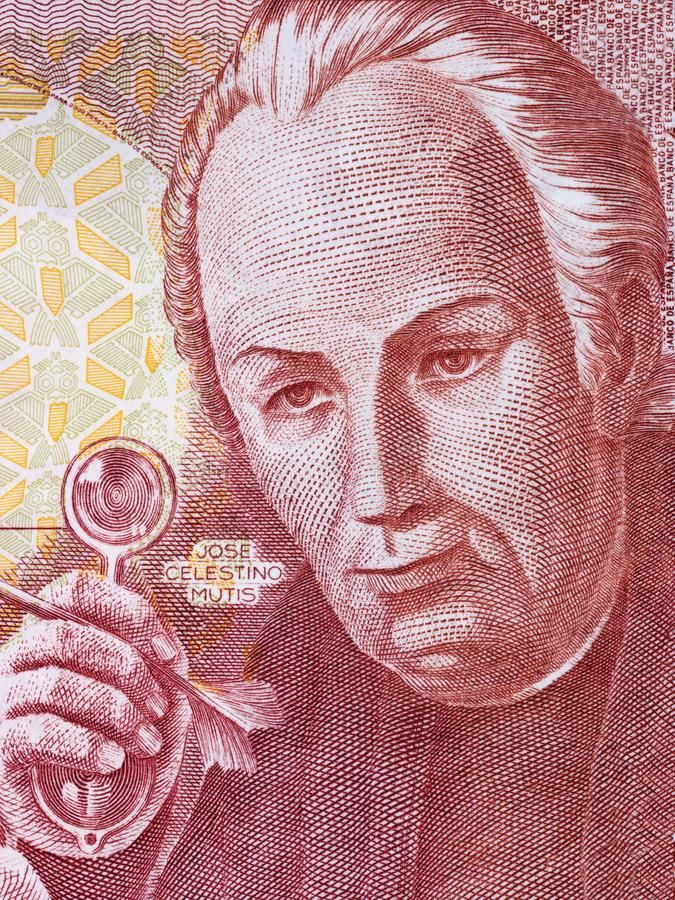

Iconography

Each banknote was designed with the intention of paying tribute to a significant event, a celebrity, or a magnificent work of art. From monarchs, painters, writers and scientists, to monuments, literary passages, or events such as the Discovery of America have had their place on the obverses and reverses of banknotes, a true reflection of the feeling, the culture and the artistic expression of the country.

Last issue

- 1.000 pesetas

- 2.000 pesetas

- 5.000 pesetas

- 10.000 pesetas

Hidden

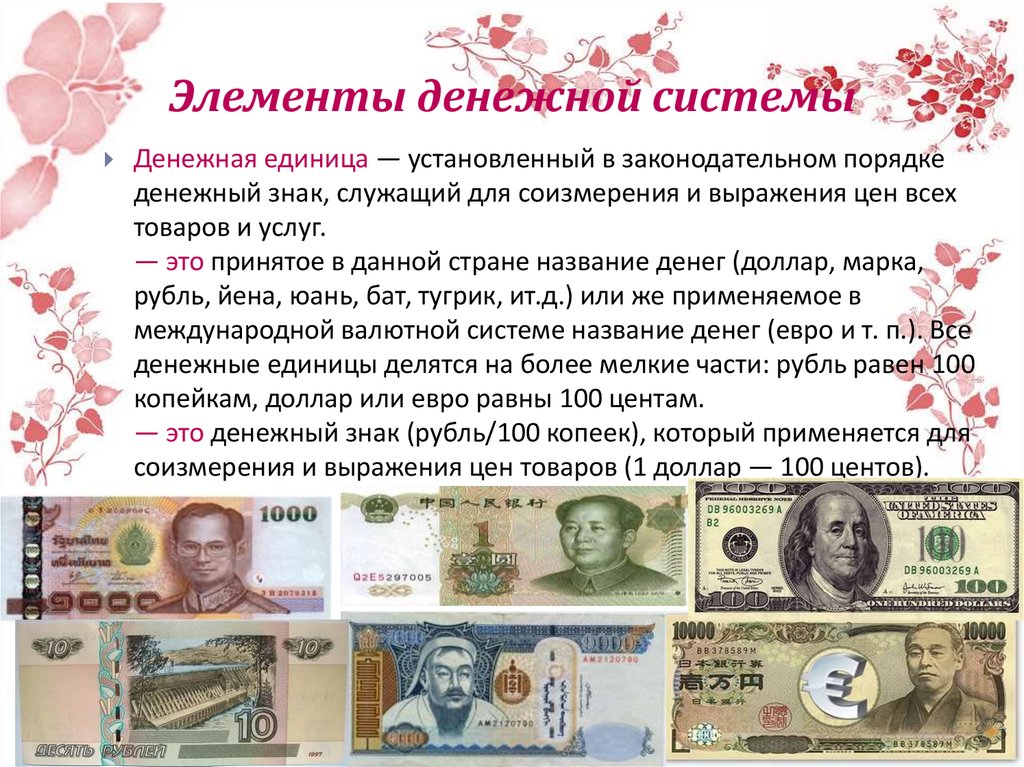

Spain coins, history of the national monetary system

Monetary unit: pesetas (ESP) = 100 centimo

| 1 peseta Spain, (1 peseta) | ||

| 1 peseta 1999 Spain | ||

| 5 pesetas 1975 Spain | ||

| 25 pesetas 1998 Spain | ||

| 100 pesetas 1996 Spain | ||

| 100 pesetas 1999 Spain | ||

| 500 pesetas 1989 Spain, (500 pesetas) |

Spain’s money history

Spain (Kingdom of Spain) – a state in southwestern Europe. It occupies most of the Iberian Peninsula.

The history of Spain has hundreds of centuries of greatness and power. The name “Spain” is of Phoenician origin. The Romans used it in the plural (Hispaniae) to refer to the entire Iberian Peninsula. The indigenous people of Spain are the Iberians. nine0003

The name “Spain” is of Phoenician origin. The Romans used it in the plural (Hispaniae) to refer to the entire Iberian Peninsula. The indigenous people of Spain are the Iberians. nine0003

In 2004, the Royal Mint of Spain supported the wonderful tradition of issuing commemorative coins to commemorate memorable dates. For the centenary of the outstanding artist – surrealist Salvador Dali – the Royal Mint of Spain has released a beautiful set of coins.

3 of them can be found in free circulation among the coins of Spain: on the reverse of one of the coins with a face value of 10 euros, an element from Salvador Dali’s painting “Leda Atomica” is depicted. The reverse of the second coin depicts the painting “Soft self-portrait with fried bacon”, in which the portrait of Dali is made in the form of a fantastic building. The third 10 euro coin depicts the painting “The Great Mastrubator”. The obverse of these coins depicts a portrait of the artist himself. nine0003

The centerpiece of the collection is a unique 50 euro coin weighing over 160 grams. Its special value lies in the fact that it has a freely removable gold-plated silver insert in the form of the famous “current” clock of Salvador Dali. The insert exactly fits into the coin, due to the fact that the image located on the side of the coin has a convex relief, and on the side of the insert it is concave. This coin will take its rightful place in the Spanish coin collection.

Its special value lies in the fact that it has a freely removable gold-plated silver insert in the form of the famous “current” clock of Salvador Dali. The insert exactly fits into the coin, due to the fact that the image located on the side of the coin has a convex relief, and on the side of the insert it is concave. This coin will take its rightful place in the Spanish coin collection.

Undoubtedly, the collectible gold coin weighing 27g and with a face value of 400 euros will take a special place among the coins of Spain. In the center of the obverse is a portrait of Dali at an older age than on the 10 euro coins. On the reverse – the famous painting by the brilliant artist “Woman at the Window”.

Currency

The Spanish national currency is the peseta (ESP). On the price tags from January last year, prices are already in pesetas and in Euros. Spanish peseta is equal to 100 centimos. The peseta was a Spanish coin that was minted from the beginning of the 18th century (5. 1 g of silver) and was equal to 1/4 peso. Since 1868, after the accession of Spain to the Latin Monetary Union, the peseta became the monetary unit of Spain, replacing the escudo. From 19In 1979, Spain began issuing banknotes that are now in circulation in the country (including the Canary Islands) and in the international banking system. The Spanish peseta is a convertible currency. There are currently four banknotes in circulation in Spain: 1,000, 2,000, 5,000 and 10,000 ESP from 1979 and 1992.

1 g of silver) and was equal to 1/4 peso. Since 1868, after the accession of Spain to the Latin Monetary Union, the peseta became the monetary unit of Spain, replacing the escudo. From 19In 1979, Spain began issuing banknotes that are now in circulation in the country (including the Canary Islands) and in the international banking system. The Spanish peseta is a convertible currency. There are currently four banknotes in circulation in Spain: 1,000, 2,000, 5,000 and 10,000 ESP from 1979 and 1992.

Banknotes from 1979-1980 are rare, as they are gradually being replaced by banknotes of similar denominations from 1992, which are better protected from counterfeiting. Banknotes of smaller denominations (100, 200, 500) were withdrawn from circulation and replaced by coins. nine0003

The import of foreign currency into Spain is not restricted (declaration is required if the amount exceeds 80,000 Spanish pesetas). The export of imported foreign currency is allowed according to the declaration. You can enter 100,000 pesetas of the national currency, withdraw 20,000. There are no problems with the exchange of imported currency in Spain, a country of developed tourism. Banks are open from Monday to Saturday from 9.00 to 16.30. True, in numerous exchange offices, the exchange rate is often favorable, and can vary greatly even on the same street. nine0003

You can enter 100,000 pesetas of the national currency, withdraw 20,000. There are no problems with the exchange of imported currency in Spain, a country of developed tourism. Banks are open from Monday to Saturday from 9.00 to 16.30. True, in numerous exchange offices, the exchange rate is often favorable, and can vary greatly even on the same street. nine0003

Sometimes they take commissions (as a rule, they don’t take them from European currencies), but they don’t always take them from the dollar either. This is always written in capital letters. But it’s better to ask (if you don’t know the language – just show your banknote), they can take from an amount up to $ 100, but not higher.

Spanish currency. History of monetary circulation in Spain.

Spanish currency before euro (real, paseta escudo)

Before the euro appeared in Spain, the history of the currency of this country was associated with three coins – the ral, escudo and peseta. By and large, all the changes that took place with the Spanish currency were the results of the new naming of old coins, which later became full-fledged monetary units. nine0003

nine0003

History of real

Real for many centuries was the main currency in the Spanish kingdom. So, it was introduced into use in the middle of the 14th century, and in 1864 it was replaced by escudo. Actually, the real was introduced by Pedro I, King of Castile. Thus, the real became a standardized coin, the equivalent of which was equal to three maravedis. By the way, maravedi are ancient Iberian coins that were minted from silver and gold. Eight reais were equal to one peso, which was also called the dollar. It began to be issued as a separate coin and was minted from silver. It must be said that Spanish coins circulated in almost all world markets, they were especially common in the markets of America and Asia. nine0003

History of escudo

The word “escudo” called two types of coins – silver and gold. The first Spanish gold escudo coin was minted in 1566, and the last in 1833. Silver began to be minted in 1864 and before the advent of a new coin – the peseta. In different periods of time, the escudo was the equivalent of a different amount of reals.

In different periods of time, the escudo was the equivalent of a different amount of reals.

History of peseta

Pesetas have been in use throughout Spain since 1869.years, and in 2002 they were replaced by the euro. As for the etymology of the word “peseta” (Spanish peseta), its origin is connected with the diminutive form of the Catalan word “Peça”. So, “peçeta” literally means “piece”. Initially, since the 15th century, this term denoted a silver coin, and in the Middle Ages, the value of 2 reales was used to name it.

In 1868, in October, a decree was issued that regulated the peseta as the national currency in order to strengthen the Spanish economy, stabilize the financial system of the state and facilitate trade. During the same period, Spain becomes a member of the Latin Monetary Union, which was created to unify several monetary systems that existed at that time in Europe. nine0003

But in 1874, namely on July 1, the mint printed the first banknotes in denominations of 25, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 pesetas. The first issued series consisted of 2 million of these banknotes, and only banks and similar financial institutions could use them.

The first issued series consisted of 2 million of these banknotes, and only banks and similar financial institutions could use them.

The following series were issued with the same denomination. This continued until 1935, when the value of silver rose and the peseta experienced a devaluation. So, coins of 5 pesetas began to be sold as a precious metal at a higher cost, the Spanish government was forced to print banknotes of 5 and 10 pesetas, which became the equivalent of the so-called “silver certificate of coins that were withdrawn from use. nine0003

The civil war led to a crisis in the Spanish economy, and the currency depreciated accordingly. So, the Bank of Spain was forced to issue banknotes in denominations of 50 centimos, as well as 1, 2, 5, 10 pesetas, since the metal used in minting was simply impossible to buy.

Thus, in 1974, there were approximately 700 million banknotes in use in Spain, and literally 4 years later – about a billion. The fact is that the largest banknote was in denomination of 1000 pesetas, and therefore the inhabitants of the country were forced to carry around a pile of papers with them in order to make a major purchase. nine0003

nine0003

In view of such circumstances, from the beginning of the 70s of the last century, banknotes of small denomination began to be withdrawn from use, and already in 1976 a banknote of 5,000 pesetas appeared. 1979 was marked by the penultimate issue of banknotes, each of which, in accordance with its value, had a certain color. In the 80s, banknotes of 2000 and 5000 pesetas appeared, and from the 82nd year they stopped issuing banknotes of 100 or less pesetas, in the 87th they issued coins that replaced banknotes of 200 and 500 pesetas. nine0003

The last series was released in 1992 (1000, 2000, 5000, 10000 pesetas), while the last series was withdrawn from circulation in 1997. In 2002, the euro was introduced. By the way, if someone still has pesetas, they can still be exchanged at the Bank of Spain, receiving euros.

I must say that the Spaniards were very sensitive to their national currency that had gone out of circulation. For example, in Estepona they even erected a monument in memory of the peseta.

The history of the emergence of the euro. nine0083

Anyone who has been to Europe knows how few differences there are between its countries when traveling through it. The fact that you are in another country is only reminded by inscriptions in another language, and nothing else. All stores accept the same banknotes, and no one is surprised by the fact that you do not need to exchange money at an unfamiliar rate and get confused with change. But it was not always so.

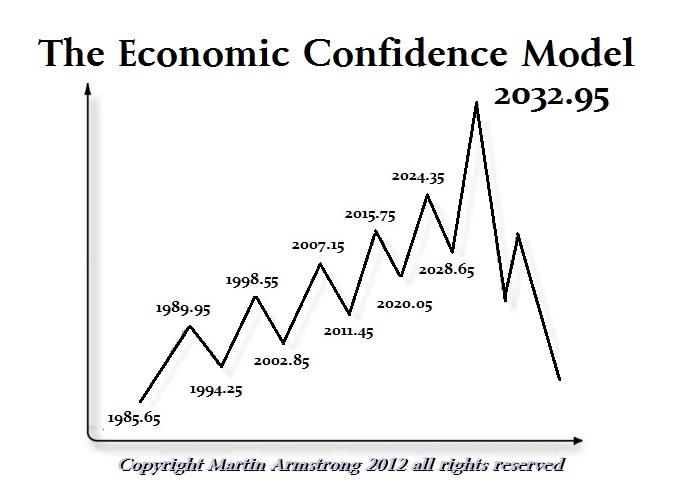

Europe is like a patchwork quilt – how many countries, so many customs. The idea of a single currency has been in the minds of many European rulers since Napoleon. But only in our days it was possible to make the transition from national currencies to the euro. nine0003

Earlier, before the formation of the European Union, European countries introduced an invisible virtual currency under the strange name “ecu”, which existed from 1979 to 1998. With the help of the ecu, all calculations were made between many European countries, but the rest of the world did not recognize the ecu and was equal to the US dollar. Europe was offended that it was not taken into account, and in 1992 the countries united in the EU in order to resist the pressure of the dollar by all, so to speak, in the world.

Europe was offended that it was not taken into account, and in 1992 the countries united in the EU in order to resist the pressure of the dollar by all, so to speak, in the world.

Instead of an inflated ecu, a more serious currency was supposed to appear that would suit everyone, and this happened. But back at 19In 1975, the artist Arthur Eisenmerger drew a sketch of the future symbol of a united Europe, which lay in the farthest safe until 1997. It was then that the President of the European Commission, Jacques Saite, ordered to make a cliché for minting the first euros.

But no one offered the European currency an easy way, and Europe found its own way to gain confidence. At first, since 1992, the euro was used only for non-cash payments between EU countries, which greatly facilitated and simplified the work of accountants and financiers. And at the same time, the peoples of Europe were getting used to the existence of a single currency, preparing for the transition to using it not only in the international financial space. nine0003

nine0003

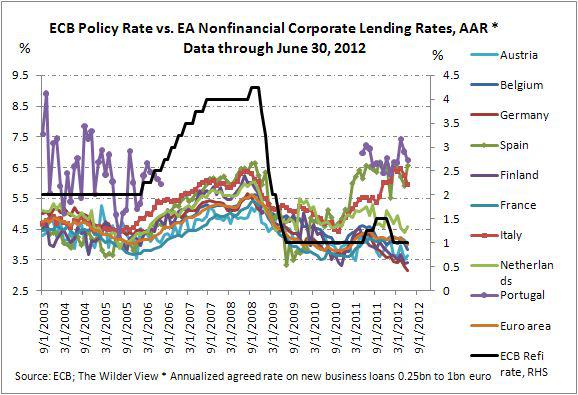

Seventeen countries – Austria, Belgium, Greece, Germany, Spain, Ireland, Italy, Cyprus, Malta, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, France, Finland and Estonia – united and signed an agreement on a single European currency. Not all countries, of course, immediately supported the idea of switching to a single currency in reality, for real. It came to oddities – Denmark categorically refused to sign the agreement, and achieved a refusal to enter into a monetary union. As soon as the official papers were issued, Denmark immediately agreed to accept the euro. nine0003

The euro was launched into free float. At first, he had circulation on a par with the official currency in each country, accustoming Europeans to his existence. Tourists immediately appreciated the convenience of the euro, and shop assistants instantly learned how to convert the national currency to the euro. National mints stopped printing new money, as the cash supply was sufficient with the advent of the euro.

By the way, the euro banknotes themselves were developed taking into account all kinds of counterfeiting attempts. The size and color of the banknotes suits all the inhabitants of Europe, because the banknotes depict the architectural and historical values of Europe, starting from the distant past and going into the distant future. The paper contains special microfibers that are in the paper pulp in a chaotic manner. These multi-colored dashes and curlicues can be seen on the surface of banknotes with the naked eye. nine0003

In addition to the microfibers, the paper itself has unique properties. It is resistant to repeated bending, practically does not wrinkle and always perfectly retains its original colors. Additional protection is provided by colored and metallized plastic ribbons, which “stitch” banknotes with a light dotted line. Many of them have special micro-inscriptions on their surface, which can only be read with a magnifying glass, which creates additional difficulties for making fakes.

When Europe got used to the euro, it was time to get rid of the old money. Unlike Russia, the countries of Europe did not set strict time limits. Within six months it was possible to get rid of all the old money by exchanging it for the euro, and this suited the well-fed Europeans quite well. There were no scandals, no bankruptcies, everything went calmly and civilized, however, as always in Europe.

If at first the euro was artificially fed by European banks, then after the first wave of the economic crisis in 2001 and a series of terrorist attacks on the United States, the dollar staggered, and the world economic communities began to take the European currency seriously, which was the beginning of its consolidation in the currency market. nine0003

And it was quite successful – the euro is successfully popular not only among European countries.