Tainos and caribs: Carib | History, Traditions, & Facts

Study puts the ‘Carib’ in ‘Caribbean,’ boosting credibility of Columbus’ cannibal claims – Florida Museum Science

Christopher Columbus’ accounts of the Caribbean include harrowing descriptions of fierce raiders who abducted women and cannibalized men – stories long dismissed as myths.

But a new study suggests Columbus may have been telling the truth.

Using the equivalent of facial recognition technology, researchers analyzed the skulls of early Caribbean inhabitants, uncovering relationships between people groups and upending longstanding hypotheses about how the islands were first colonized.

One surprising finding was that the Caribs, marauders from South America and rumored cannibals, invaded Jamaica, Hispaniola and the Bahamas, overturning half a century of assumptions that they never made it farther north than Guadeloupe.

“I’ve spent years trying to prove Columbus wrong when he was right: There were Caribs in the northern Caribbean when he arrived,” said William Keegan, Florida Museum of Natural History curator of Caribbean archaeology. “We’re going to have to reinterpret everything we thought we knew.”

“We’re going to have to reinterpret everything we thought we knew.”

Caribs hailed from the Northwest Amazon, and archaeologists long believed they never expanded north of the Lesser Antilles.

Detail from a painting by John Gabriel Stedman. Public domain image

Columbus had recounted how peaceful Arawaks in modern-day Bahamas were terrorized by pillagers he mistakenly described as “Caniba,” the Asiatic subjects of the Grand Khan. His Spanish successors corrected the name to “Caribe” a few decades later, but the similar-sounding names led most archaeologists to chalk up the references to a mix-up: How could Caribs have been in the Bahamas when their closest outpost was nearly 1,000 miles to the south?

But skulls reveal the Carib presence in the Caribbean was far more prominent than previously thought, giving credence to Columbus’ claims.

Face to face with the Caribbean’s earliest inhabitants

Previous studies relied on artifacts such as tools and pottery to trace the geographical origin and movement of people through the Caribbean over time. Adding a biological component brings the region’s history into sharper focus, said Ann Ross, a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University and the study’s lead author.

Adding a biological component brings the region’s history into sharper focus, said Ann Ross, a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University and the study’s lead author.

Ross used 3D facial “landmarks,” such as the size of an eye socket or length of a nose, to analyze more than 100 skulls dating from about A.D. 800 to 1542. These landmarks can act as a genetic proxy for determining how closely people are related to one another.

The analysis not only revealed three distinct Caribbean people groups, but also their migration routes, which was “really stunning,” Ross said.

Researchers used 16 facial “landmarks” to analyze skulls, a technique often used as a genetic proxy. “You can tell how closely people are related or not by these types of measures,” Ross said.

For the past 30 years, archaeologists have debated how the Caribbean was settled and by whom. The skull analysis revealed three distinct people groups and migrations. One previous hypothesis proposed the Caribbean’s colonizers included people from Florida and Panama, but the researchers did not find biological evidence to support this line of thinking.

Looking at ancient faces shows the Caribbean’s earliest settlers came from the Yucatan, moving into Cuba and the Northern Antilles, which supports a previous hypothesis based on similarities in stone tools. Arawak speakers from coastal Colombia and Venezuela migrated to Puerto Rico between 800 and 200 B.C., a journey also documented in pottery.

The earliest inhabitants of the Bahamas and Hispaniola, however, were not from Cuba as commonly thought, but the Northwest Amazon – the Caribs. Around A.D. 800, they pushed north into Hispaniola and Jamaica and then the Bahamas where they were well established by the time Columbus arrived.

“I had been stumped for years because I didn’t have this Bahamian component,” Ross said. “Those remains were so key. This will change the perspective on the people and peopling of the Caribbean.”

For Keegan, the discovery lays to rest a puzzle that pestered him for years: why a type of pottery known as Meillacoid appears in Hispaniola by A. D. 800, Jamaica around 900 and the Bahamas around 1000.

D. 800, Jamaica around 900 and the Bahamas around 1000.

Keegan had been stumped for years by the appearance of a distinct type of pottery in Hispaniola, Jamaica and the Bahamas. He now believes it is the cultural fingerprint of a Carib invasion and likely originated in the Carib homeland of South America.

Florida Museum photo by William Keegan

“Why was this pottery so different from everything else we see? That had bothered me,” he said. “It makes sense that Meillacoid pottery is associated with the Carib expansion.”

The sudden appearance of Meillacoid pottery also corresponds with a general reshuffling of people in the Caribbean after a 1,000-year period of tranquility, further evidence that “Carib invaders were on the move,” Keegan said.

Raiders of the lost Arawaks

So, was there any substance to the tales of cannibalism?

Possibly, Keegan said.

Arawaks and Caribs were enemies, but they often lived side by side with occasional intermarriage before blood feuds erupted, he said.

“It’s almost a ‘Hatfields and McCoys’ kind of situation,” Keegan said. “Maybe there was some cannibalism involved. If you need to frighten your enemies, that’s a really good way to do it.”

Whether or not it was accurate, the European perception that Caribs were cannibals had a tremendous impact on the region’s history, he said. The Spanish monarchy initially insisted that indigenous people be paid for work and treated with respect, but reversed its position after receiving reports that they refused to convert to Christianity and ate human flesh.

“The crown said, ‘Well, if they’re going to behave that way, they can be enslaved,’” Keegan said. “All of a sudden, every native person in the entire Caribbean became a Carib as far as the colonists were concerned.”

The study was published in Scientific Reports.

Michael Pateman of the Turks and Caicos National Museum and Colleen Young of the University of Missouri also co-authored the study.

The research was funded by the National Museum of the Bahamas’ Antiquities, Monuments and Museum Corporation and the Florida Museum’s Caribbean Archaeology endowment.

Editor’s note: You can read more about this work in this piece from North Carolina State University.

Sources: William Keegan, [email protected], 352-273-1921;

Ann Ross, [email protected], 919-515-3122

Carib – New World Encyclopedia

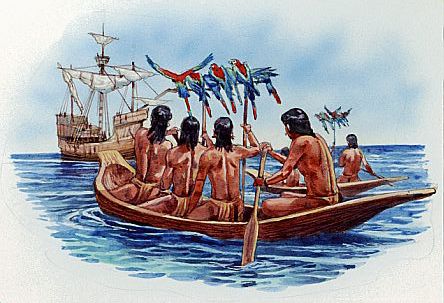

Carib family (by John Gabriel Stedman)

Carib, Island Carib, or Kalinago people, after whom the Caribbean Sea was named, live in the Lesser Antilles islands. They are one of the two main tribes of Amerindian people who inhabited the Caribbean at the time of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the New World, the other being the Taino (also known as the Arawak).

Like most of the indigenous peoples of the New World, the Carib suffered greatly from European Colonization of the Americas European conquest, and their descendants are now scattered throughout the Caribbean and South America, with the largest group living on the island of Dominica where the British established a reservation for them.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Culture

- 3 Contemporary life

- 4 Notes

- 5 References

- 6 External links

- 7 Credits

Often the Carib are remembered for being ferocious warriors and for cannibalistic customs. Although it may be true that they were warlike, fighting and displacing other tribes such as the Taino, they have often been maligned by exaggerated early European propaganda that over-looked their many accomplishments and skills, such as sailing, navigation, and basket weaving. Today, Carib make effort to preserve their culture and educate their children and others about their traditions, maintaining their identity while at the same time being part of the contemporary society.

History

Although the precise time frame remains unknown, it is generally believed that the Taino were the first group to migrate from the Orinoco river area in South America to the islands of the Caribbean, sometime around 500 B. C.E.[1] The Carib followed soon afterward, invading many areas the inhabited by the Taino, killing and subjugating their predecessors. By 1400 C.E., the Carib controlled most of the West Antilles and areas of the cost of Venezuela.[2] After years of hostility, the two tribes settled into a general peace and cooperation, trading amongst each other and in some areas, such as the island now known as Dominica, the two cultures blended together.[1]

C.E.[1] The Carib followed soon afterward, invading many areas the inhabited by the Taino, killing and subjugating their predecessors. By 1400 C.E., the Carib controlled most of the West Antilles and areas of the cost of Venezuela.[2] After years of hostility, the two tribes settled into a general peace and cooperation, trading amongst each other and in some areas, such as the island now known as Dominica, the two cultures blended together.[1]

In 1493, during his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus landed on the island the Carib had named Waitukubuli, which translates as “Tall is her beauty.” Columbus renamed the island “Dominica,” from the Latin Domingo, which means “Sunday.”[1] Columbus’ first encounter with the Carib was marked by the natives’ hostility towards the Europeans. Whereas history records Columbus was welcomed and made quick connections with the Tainos he encountered, Columbus and the Carib were almost immediately at odds with one another. After a few small but fierce skirmishes, Columbus and his men withdrew from the island of Dominica. Columbus named these natives Caniba, after the land other tribes referred to as Caritaba, where fierce cannibal warriors lived.[3] Eventually the Caribs warmed to the Europeans and trade developed. However, further European conquest soon proved the disastrous for the them.

After a few small but fierce skirmishes, Columbus and his men withdrew from the island of Dominica. Columbus named these natives Caniba, after the land other tribes referred to as Caritaba, where fierce cannibal warriors lived.[3] Eventually the Caribs warmed to the Europeans and trade developed. However, further European conquest soon proved the disastrous for the them.

The 1635 invasion and seizure by the French military of the island of Martinique, which lies southeast of Dominica and was also populated by Caribs, made it part of the French colonial empire. Using their overwhelming military superiority, the French forces of Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc subjugated the indigenous Carib peoples to French colonial rule. Through Cardinal Richelieu, France gave the island to the Company of the American Islands (Compagnie des Isles d’Amerique). French Law was imposed on the conquered inhabitants and the Jesuits arrived to convert them to the Roman Catholic Church. [4] When the Caribs could not be sufficiently induced to supply labor for building and maintaining the sugar and cocoa plantations the Company desired, in 1636 King Louis XIII authorized the abduction of slaves from Africa for transportation to Martinique and other parts of the French West Indies.[5] The Caribs revolted against French rule and under Governor Charles Houel sieur de Petit Pré the “Carib Expulsion” was launched against them in 1660. Many were slaughtered; those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island, never to return.

[4] When the Caribs could not be sufficiently induced to supply labor for building and maintaining the sugar and cocoa plantations the Company desired, in 1636 King Louis XIII authorized the abduction of slaves from Africa for transportation to Martinique and other parts of the French West Indies.[5] The Caribs revolted against French rule and under Governor Charles Houel sieur de Petit Pré the “Carib Expulsion” was launched against them in 1660. Many were slaughtered; those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island, never to return.

By the eighteenth century the British Empire had moved in and begun to threaten the French and Spanish colonies. In 1763 the British captured the island of Dominica and forced the Carib onto a reserve of 232 acres (94 ha), while the British took control of the rest of the island and consumed its natural wealth and resources.[3] The Carib on Dominica, although confined to a small part of the island, fared better than other tribes on other islands.

In 1796, the British Empire took control of large parts of the Caribbean. The population of Saint Vincent, known as the “Black Carib” because a slave ship had wrecked on the island in the seventeenth century and surviving African slaves had intermarried with the Carib Indians, were relocated to an island off the coast of Honduras where they suffered from disease and maltreatment. However, enough were able to make it off the island and survive in small numbers in Central America.[2] Across the rest of the Caribbean, the Carib and other indigenous tribes were decimated in numbers by the European suppression, disease, and the Inquisition. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Carib existed primarily on the reserve in Dominica with a few groups scattered in Central America.

Culture

Carib woman in traditional dress, typically cotton pants.

Much of the historical narrative of the Carib culture has focused upon their aggressive and war-like characteristics. The Taino’s experiences of fighting and being conquered by the Carib influenced Columbus’ account of the Carib tribes. In fact, it was Columbus’ second hand knowledge and limited personal contact with the Carib that led to the creation of the word cannibal. The English word “cannibal” originated from the Carib word karibna (“person”), as recorded by Columbus as a name for the Caribs.[6]

The Taino’s experiences of fighting and being conquered by the Carib influenced Columbus’ account of the Carib tribes. In fact, it was Columbus’ second hand knowledge and limited personal contact with the Carib that led to the creation of the word cannibal. The English word “cannibal” originated from the Carib word karibna (“person”), as recorded by Columbus as a name for the Caribs.[6]

The existence of cannibalism has been challenged by some anthropologists as well as contemporary Carib.[7] However, there is significant historic evidence that instances of cannibalism were spiritual acts connected to deeply held war rituals; purportedly, male warriors would eat small amounts of the flesh of their enemies so as to assume their characteristics.[6] This ritual eating of human flesh took place before a raiding expedition or during initiation, when it was hoped young men would inherit the bravery of a distinguished warrior.[8] More commonly though, the Carib would collect the limbs of victims as trophies, and had a tradition of keeping the bones of their ancestors in their houses. The belief that the physical remains of the dead could be used to harvest some residual power of the living was central to Carib spirituality.

The belief that the physical remains of the dead could be used to harvest some residual power of the living was central to Carib spirituality.

Caraib indians, one of them wearing a tattoo. P. J. Benoît, 1839.

Because of a possible shared ancestry and years of assimilation, the Caribs shared many cultural similarities with the Tainos. Both are generally thought to have been polytheists, who believed in nature spirits and practiced forms of shamanism. The Carib believed in an evil spirit called Maybouya who had to be placated in order to avoid harm. The chief function of their shamans was to heal the sick with herbs and to cast spells which would keep Maybouya at bay. The shamans underwent special training instead of becoming warriors. As they were held to be the only people who could avert evil, they were treated with great respect. Their ceremonies were accompanied with sacrifices. As with the Taino, tobacco played a large part in these religious rites.

The fact they were able to migrate from the continent to various islands in the Caribbean, as well as conquer already populated islands are testaments both to their skills as navigators and boat builders. The Carib were also skilled at basket weaving and pottery. The tribes subsisted on fishing and small scale farming.

The social structure of Carib tribes were mostly patriarchal. The men trained as warriors, traveling by canoe on raiding parties. Women primarily carried out domestic duties and farming, and often lived in separate houses from the men. However, women were highly revered and held substantial socio-political power. The Caribs usually lived in small groups, but these groups were often not exclusive from one another.

After successfully conquering parts of the Caribbean, the Carib language quickly died out while the Arawakan language was maintained over the generations. This was the result of the invading Carib men usually killing the local men of the islands they conquered and taking Arawak wives who then passed on their own language to the children. For a time, Arawak was spoken primarily or exclusively by women and children, while adult men spoke Carib.[9] Eventually, as the first generation of Carib-Arawak children reached adulthood, the more familiar Arawak became the only language used in the small island societies. This language was called Island Carib, even though it is not part of the Carib linguistic family. It is now extinct, but was spoken on the Lesser Antilles until the 1920s (primarily in Dominica, Saint Vincent, and Trinidad).[9]

For a time, Arawak was spoken primarily or exclusively by women and children, while adult men spoke Carib.[9] Eventually, as the first generation of Carib-Arawak children reached adulthood, the more familiar Arawak became the only language used in the small island societies. This language was called Island Carib, even though it is not part of the Carib linguistic family. It is now extinct, but was spoken on the Lesser Antilles until the 1920s (primarily in Dominica, Saint Vincent, and Trinidad).[9]

Contemporary life

Map of Carib Territory on the Island of Dominica.

Today, small pockets of ethnic Carib communities are scattered throughout the Caribbean and South America, in such places as Trinidad, Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana and Suriname. The largest community lives on the island of Dominica, in the original reservation established for the Carib by the British in the eighteenth century. An estimated community of 3,400 people live in this reservation. [8] This community elects their own Chiefs who serve for four years at a time, and officials who represent the Carib in the Dominica government.[10] These communities have made efforts to keep their historical traditions and culture alive, partially for preservation but also for economic reasons, as the Carib territories are marketed as tourist attractions where visitors can view cultural acts such as dance as well as purchase authentic crafts and artwork. The Carib community has established the Karifuna Cultural Group which works to preserve their culture and to support education about Carib history and tradition.[10]

[8] This community elects their own Chiefs who serve for four years at a time, and officials who represent the Carib in the Dominica government.[10] These communities have made efforts to keep their historical traditions and culture alive, partially for preservation but also for economic reasons, as the Carib territories are marketed as tourist attractions where visitors can view cultural acts such as dance as well as purchase authentic crafts and artwork. The Carib community has established the Karifuna Cultural Group which works to preserve their culture and to support education about Carib history and tradition.[10]

Garinagu at the San Isidro Labrador street celebration in Livingston (Guatemala).

The Santa Rosa Carib Community (SRCC) is the major organization of indigenous people in Trinidad and Tobago. The Caribs of Arima are descended from the original Amerindian inhabitants of Trinidad; Amerindians from the former encomiendas of Tacarigua and Arauca (Arouca) were resettled to Arima between 1784 and 1786. The SRCC was incorporated in 1973 to preserve the culture of the Caribs of Arima and maintain their role in the annual Santa Rosa Festival (dedicated to Santa Rosa de Lima, the first Catholic saint canonized in the New World).

The SRCC was incorporated in 1973 to preserve the culture of the Caribs of Arima and maintain their role in the annual Santa Rosa Festival (dedicated to Santa Rosa de Lima, the first Catholic saint canonized in the New World).

Today, the Garinagu (singular: Garifuna), descendants of Carib, Arawak, and African people referred to by the British colonial administration as “Black Carib” live primarily in Central America. They live along the Caribbean Coast in Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras, and on the island of Roatán. There are also diaspora communities of Garinagu in the United States, particularly in Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and other major cities.

Notes

- ↑ 1.01.11.2 Kevin Menhinick, “The Caribs in Dominica: Karifuna Cultural Group,” Caribbean Taino News Service, 1997. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ 2.02.1 Jan Rogonzinski, A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present (Plume, 2000, ISBN 0452281938).

- ↑ 3.03.1 Kwabs.com, “Caribbean Indigenous people.” Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Prefecture Région Martinique, Martinique’ Institutional History, Maryanne Dassonville (trans.), 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ James L. Sweeney, “Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent,” African Diaspora Archaeology Network, March 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ 6.06.1 Laurance R. Goldman (ed.), The Anthropology of Cannibalism (Bergin & Garvey Paperback, 1999, ISBN 0897895975).

- ↑ Lennox Honychurch, The Dominica Story: A History of the Island (Macmillan Caribbean, 1995, ISBN 0333627768).

- ↑ 8.08.1 Simon Lee, “An Artist of the Floating World,” The Caribs of Dominica, 2000. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ 9.09.1 Ellen B. Basso, Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1977, ISBN 0816504938).

- ↑ 10.010.1 A Virtual Dominica, “The Carib Indians.” Retrieved February 25, 2009.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allaire, Louis. “The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles.” In Samuel M. Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1997. ISBN 0813015316.

- Basso, Ellen B. Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language. University of Tucson, AZ: Arizona Press, 1977. ISBN 0816504938.

- Davis, D., and Goodwin R. C. “Island Carib Origins: Evidence and non-evidence.” American Antiquity 55(1) (1990).

- Eaden, John. The Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693-1705. Frank Cass, 1970.

- Goldman, Laurance R. (ed.). The Anthropology of Cannibalism. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey Paperback, 1999. ISBN 0897895975.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition.

Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2009. - Honeychurch, Lennox. The Dominica Story: A History of the Island. Macmillan Caribbean, 1995. ISBN 0333627768.

- Rogonzinski, Jan. A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present. New York, NY: Plume, 2000. ISBN 0452281938.

- Steele, Beverley A. Grenada: A History of its People. Macmillan Education, 2003. ISBN 0333930533.

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Ethnologue report for Carib language

- O! Dominica Land of Beautiful Indigenous People

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Carib history

- Carib_Expulsion history

- Cariban_languages history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of “Carib”

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Oetker collection

A few words about the Oetker Collection

The Oetker Collection is an exclusive collection of luxury hotels that includes 12 hotels worldwide. All hotels are united by the name Masterpiece Hotels and are distinguished by the highest level of service.

Each of them is unique in its own way and lovingly preserves its historical past.

The symbol of the Oetker collection is a pearl necklace, in which each of the pearls is the embodiment of individuality, beauty and quality.

The Oetker Collection is committed to the environment and is an active member of the UN Global Compact, the world’s largest corporate social responsibility and sustainability initiative.

The Oetker collection includes 12 luxury hotels:

– L’Apogee Courchevel at the top of the former Olympic ski jump in the center of the Jardin Alpin in Courchevel 1850, one of the world’s best ski resorts.

– Brenners Park-Hotel & SPA in Baden-Baden, a legendary grand hotel located in the middle of a private park. In January 2015, the hotel opened the innovative SPA center Villa Stéphanie with the medical complex Haus Julius.

– Le Bristol Paris in Paris, the first hotel in France to receive the status of Palace, is located on the prestigious rue Faubourg Saint-Honore, a stone’s throw from the Champs Elysées and the Place de la Concorde.

– The Woodward in Geneva, a new collection hotel that opened in 2021. The hotel is located on the Quai Wilson on the shores of Lake Geneva. Each of the 26 Suites has its own distinct character and individual décor. Two world-class gastronomic restaurants, one of which was awarded 1* Michelin in October 2022, as well as Spa by Maison Guerlain.

The hotel is located on the Quai Wilson on the shores of Lake Geneva. Each of the 26 Suites has its own distinct character and individual décor. Two world-class gastronomic restaurants, one of which was awarded 1* Michelin in October 2022, as well as Spa by Maison Guerlain.

– NEW! Hotel La Palma in Capri, a new hotel of the collection that will open in 2023. The hotel is located in lively Capri, the main town of the island, just a few steps from the famous Piazzetta, and after the completion of the renovation, it will open 50 rooms and Suites, a rooftop restaurant and bar, its own beach club, swimming pool, SPA center and fashion boutiques. In keeping with the Oetker Collection’s core mission of creating meaningful connections in special places, the brand’s first Italian hotel will embody the island’s iconic dolce vita.

– Chateau Saint-Martin & SPA , built on the ruins of an ancient Templar castle, is a place for secluded relaxation in the heart of Provence.

– Eden Rock St Barths the epitome of French art-de-vivre in the Caribbean, built on a rocky promontory; icon and symbol of St. Barth.

– Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc in Cape d’Antibes, one of the most luxurious places on the French Riviera. For more than 140 years, the legendary hotel has been a favorite vacation spot for the world’s elite.

– The Lanesborough is a classic of British service in the immaculate setting of a London residence / a true embodiment of the spirit of old England.

– Palácio Tangará is a colonial-style mansion surrounded by tropical trees, located in the middle of Burle Marx Park, in the heart of vibrant São Paulo.

– Jumby Bay Island, Antigua – West Indies – a private island in the Caribbean, located opposite the main island of Antigua; 120 hectares of white sandy beaches, greenery and turquoise waters of the Caribbean Sea.

– NEW! The Vineta Hotel , Palm Beach, USA – The collection’s first American hotel is scheduled to open in late 2023 in partnership with Reuben Brothers. The hotel will be the 12th in the Oetker collection and is located in the heart of Palm Beach – two blocks from Worth Avenue with its designer boutiques, art galleries and upmarket restaurants and within walking distance of the beach.

The hotel will be the 12th in the Oetker collection and is located in the heart of Palm Beach – two blocks from Worth Avenue with its designer boutiques, art galleries and upmarket restaurants and within walking distance of the beach.

DUPONT

0074 DUPONT

| Product name | Quantity DW | Preparative Form | Packing | Price for 1 l/kg including VAT (18%), rub | |||||

| Herbicides | |||||||||

| Basis | 500+250g/kg | STS | 0. 1kg/ban 1kg/ban | ||||||

| Granstar Pro | 750g/kg | VDG | 0.5kg/ban | ||||||

| Granstar Pro+Dianat | VDG | ||||||||

| Caliber | 250+500g/kg | VDG | 0.5kg/ban | ||||||

| Caribou | 500g/kg | SP | 0.6kg/pack | ||||||

| Cordus | 500+250g/kg | VDG | 10×0. 4 4 | ||||||

| Cortes | 750g/kg | SP | 0.04kg/ban | ||||||

| Laren Pro | 600g/kg | VDG | 0.1kg/ban | ||||||

| Segment | 500g/kg | VDG | 0.25kg/ban | ||||||

| Titus Plus | 906+32.5g/kg | VDG | 0.768kg/ct | ||||||

| Titus | 250g/kg | STS | 0. 5kg/ban 5kg/ban | ||||||

| Phineas Light | 333.75+333g/kg | VDG | 0.09kg/ban | ||||||

| Harmony | 750g/kg | STS | 0.1kg | ||||||

| Elli Light | 391+261g/kg | VDG | 0.08kg/ban | ||||||

| Fungicides | |||||||||

| Kurzat | 689. | ||||||||

Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2009.