Which currency is used in spain: Currency in Spain. Where to exchange money and how to pay

Currency in Spain: A Complete Guide

Find out what currency is used in Spain, tips and tricks for Spanish currency exchange, and how you can save money on your visit with the Wise euro card.

Learn about the euro card

What is the currency in Spain?

The currency in Spain is the euro. Each euro is divided into 100 cents.

When you’re buying currency for Spain, look out for the currency code EUR. And once you’re in Spain, you’ll see the symbol € used to show prices.

You’ll find Euro banknotes in denominations of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 – although the 200 and 500 EUR notes are seldom used. There are also 1 and 2 euro coins.

Cents come in coins of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50.

Use the Wise euro card to spend in Spanish currency.

The Wise euro travel money card lets you top up in your local currency, and switch to euro to spend when you’re in Spain. You’ll get the best rate for spending in euro – and can also hold and spend 50+ other currencies with the same card.

Get your Wise travel money card online for free, to send and spend money around the world at the real exchange rate.

Simply top up your card and convert to the currency you need in real time using the Wise app.

You’ll always get the real exchange rate with no hidden costs, and you’ll avoid foreign transaction fees while withdrawing from ATMs abroad, paying in restaurants and shops, and buying your accommodation and flights.

Learn more about the euro card

Tips for exchanging currency in Spain.

- The mid-market rate is the true exchange rate – with no sneaky hidden fees. Use an online currency converter before your trip to get a feel for what your money is worth and make sure you get a fair rate when you buy your travel money.

Familiarise yourself with the mid-market rate before your trip.

Convert GBP to EUR >

- Being offered to pay in your own currency at an ATM is a sneaky trick and causes many travellers to pay more than they need to. Always choose to pay in the local currency – in this case, euro – to cut your costs and get the best rates available.

Choose to be charged in Spain currency when withdrawing from ATMs.

- Currency exchange desks at airports and hotels often markup the exchange rates they use, and may charge hidden fees. Avoid this expensive option whenever you can.

Avoid changing currency at airports or hotels.

- Withdraw money, pay for meals in restaurants or spend in shops in euro, all at the real exchange rate with the Wise debit card.

Use the Wise debit card to spend in Spain without rip-off fees.

Get your travel money card >

Spending money in Spain.

Paying by credit or debit card in Spain

Credit and debit card payments are common in Spain. However, there may be limits imposed by the merchant which mean you have to use cash for smaller purchases under about EUR10. Keep cash on hand so you don’t get caught out.

Keep cash on hand so you don’t get caught out.

ATMs in Spain

You’ll be able to find ATMs easily in Spain if you’re in an urban area or popular tourist resort.

To get the best deal when spending on card or withdrawing money in Spain, don’t forget to use the Wise travel money card to avoid sneaky exchange rate markups and excessive fees.

Spanish currency services.

Convert GBP to euro

Use our currency converter to see how much your money is worth in euro and familiarise yourself with the mid-market rate before your trip.

Send money to Spain

Need to send GBP to Spain? Use Wise for fast, low-cost, and secure online money transfers from the United Kingdom to Spain.

See the best euro exchange rates

Other helpful currency guides.

Spanish currency FAQs.

Get your Wise debit card and save on your trip to Spain.

Spend smart, save money. Avoid sneaky bank fees when travelling, with Wise.

Order your card now

How much currency you need to go on vacation to Barcelona, Spain

Planning your trip to Barcelona? Know how much currency you need to make sure you have a great trip! Don’t forget to check out our guide for your stay in London, too.

Transportation

In our how much currency to bring abroad chart below, you’ll see a 10-mile cab ride is on average about $26.98 USD in Barcelona, Spain. Having this information on hand will give you a good idea of how much you would need to get around the city.

Food

In Spain, you’re sure to eat some delicious cuisine. We recommend the restaurant Bodega Biarritz, where you can enjoy delicious and authentic Spanish dishes. As shown in our how much currency to bring abroad chart above, it costs on average $28.92 USD for a budget dinner for two and $3.61 USD for a pint of beer.

Currency: The Euro (EUR)

The euro banknote has seven different denominations: €5, €10, €20, €50, €100, €200, and €500. If you haven’t brushed up on your European history recently, you may be surprised to find that Spain has utilized the euro as its main currency since 2002, after officially joining the European Union.

If you haven’t brushed up on your European history recently, you may be surprised to find that Spain has utilized the euro as its main currency since 2002, after officially joining the European Union.

Don’t forget to add CXI’s Currency Price Protection with your euros – available at our CXI City Center locations. If you have leftover euros after your trip to Barcelona, CXI will buy protected currencies back from you at our ultimate buy-back rate plus no exchange fee! Order your European Union euros now.

Flights

Roundtrip tickets to Barcelona, Spain for two typically range from about $1,232 USD to about $2,702 USD, depending on where you leave from, the airline you fly with, and when you are taking your trip, according to Expedia. January through April appear as the best months to fly to Barcelona in order to get cheaper flight prices, according to cheapflights.com. There you can find the best days of the week and the best time of year to book flights for your trips to other countries! Don’t forget before you book that flight, check out everything you need to know about the five trusted travelers programs in our video below.

Vacation rentals

Hotels in Barcelona, while lavish, can be extremely expensive. In order to get the best bang for your…euro, you should consider trying something a little different to experience the city like a local. Take a look at some of the best-rated super host places to stay in Barcelona, Spain from Airbnb.

Get more travel tips and news >

About Currency Exchange International

Currency Exchange International, CXI, is the leading provider of comprehensive foreign exchange services, risk management solutions and integrated international payments processing technology in North America. CXI’s relationship-driven approach ensures clients receive tailored solutions and world-class customer service. Through innovative and trusted FX software platforms, CXI delivers versatile foreign exchange services to our clients, so that they can efficiently manage and streamline their foreign currency and global payment needs. CXI is a trusted partner among financial institutions, corporations and retail markets around the world. To learn more, visit: www.ceifx.com

CXI is a trusted partner among financial institutions, corporations and retail markets around the world. To learn more, visit: www.ceifx.com

Disclaimer: All product names, logos, and brands are property of their respective owners. All company, product and service names used in this website are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, and brands does not imply endorsement.

Tags:

How much currency,

Travel tips,

Barcelona,

Spain,

Euro,

Currency Exchange International,

Food,

Taxi,

Trusted traveler,

International traveler

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments powered by Disqus.

Euro (€) – The official currency of Spain on Turister.ru » (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain). The euro is also used in 9 other countries of the world, 7 of which are in Europe. Thus, it is the common currency of more than 320 million Europeans. With territories using euro-based currencies, nearly 500 million people around the world depend on the euro. With a turnover of 610 billion euros since December 2006, the euro is the currency with the largest total amount of cash in circulation in the world, surpassing even the US dollar.

In 1999, the world financial markets were offered the euro as the currency of account, and on January 1, 2002, banknotes and coins were put into circulation. The Euro has replaced the previous European Currency Unit (ECU) at a one-to-one ratio.

The Frankfurt-based European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurosystem (consisting of the central banks of the Eurozone countries) govern and manage all euro transactions. As an independent central bank, the ECB has the exclusive right to determine monetary policy. The Eurosystem participates in the issuance of banknotes and coins, as well as their distribution to all countries, and in the operation of the settlement systems of the Eurozone.

As an independent central bank, the ECB has the exclusive right to determine monetary policy. The Eurosystem participates in the issuance of banknotes and coins, as well as their distribution to all countries, and in the operation of the settlement systems of the Eurozone.

While all European Union (EU) countries can be admitted to the Eurozone if they agree to certain monetary requirements, not all EU members have chosen to accept this currency. All states that joined the EU before the entry into force in 1993 of the Maastricht Treaty pledged to accept the euro according to the exchange rate.

This treaty obliged the current members to introduce the euro into circulation; however, Great Britain and Denmark secured for themselves the abolition of this requirement.

Sweden refused to adopt the euro in a 2003 referendum and circumvented the requirement to adopt the euro by not supporting this membership criterion. In addition, three microstates of Europe (Vatican, Monaco and San Marino), although they are members of the European Union, have adopted the euro as the single currency of the participating countries. Andorra, Montenegro and Kosovo adopted the euro unilaterally, although they were also not part of the EU.

Andorra, Montenegro and Kosovo adopted the euro unilaterally, although they were also not part of the EU.

Coins

The euro consists of 100 cents (sometimes called euro cents, especially to distinguish them from US cents or the former currency in a particular country). All euro coins in circulation (including €2 commemorative coins) have the same denomination (value) side showing the first 15 EU countries. From 2007 or 2008 (depending on the country that issued the coin), this “old” map will be replaced by a map of Europe showing non-EU countries such as Norway. The coins also have a national side, with a special image chosen by the country that issued the coin. Euro coins from any country can be freely used in all states that have adopted the euro.

Euro coins are issued in denominations of €2, €1, €0.50, €0.20, €0.10, €0.05, €0.02, and €0.01. In the Netherlands and Finland, by law, all cash transactions are rounded to the nearest five cents to avoid the use of €0. 02 and €0.01 (See also the linguistic article on the euro.)

02 and €0.01 (See also the linguistic article on the euro.)

€2 commemorative coins were issued with changes in the design of the national side of the coin – in connection with the Summer Olympic Games in Greece. These two euro coins are legal tender throughout the Eurozone. Coins of a different denomination were also issued, but were not intended for widespread circulation. Later coins can only be legally used in the country of origin.

Malta

Monaco

Vatican

Finland

Banknotes

In all banknotes of the euro the same design of the parties for each nominal. Banknotes are issued in denominations of €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10, €5. The design of each of them is connected with the general theme of European architecture of different periods. On the front side of the banknote, windows or gates are depicted, and on the reverse side – bridges. It is noteworthy that these architectural objects do not actually exist, so as not to provoke envy and disputes when choosing those cultural monuments that should be depicted on banknotes. Some higher denominations, such as the €500, are not issued in some countries, although they remain legal tender in the Eurozone.

Some higher denominations, such as the €500, are not issued in some countries, although they remain legal tender in the Eurozone.

Clearing system, electronic payment transfer system.

All money transfers within Eurozone countries must cost the same as transfers within the same country. This also applies to retail payments, although the ECB may use some other payment methods.

Credit/debit card payments and ATM withdrawals across Europe are also subject to the same billing. The ECB has not standardized the processing of payments for “paper” money orders such as cheques; they are only valid within a single country.

The ECB has installed the TARGET (Trans-European Automated Real Time Gross Settlement) clearing system for large euro transactions.

| 5 Euro | |

| 10 Euro | |

| 20 Euro | |

| 50 Euro | |

| 100 Euro | |

| 200 Euro | |

| 500 Euro | |

Euro graphic

The special graphic euro sign (€) was designed based on the results of a public opinion poll, selecting 2 options out of ten. And then the European Commission chose one of them as the final option. The winning project was created by the Belgian Alain Billier. The official version of the euro sign’s creation is disputed by Arthur Eisenmenger, a former leading graphic designer for the EEC, who claims to have created the sign as a common symbol for Europe.

And then the European Commission chose one of them as the final option. The winning project was created by the Belgian Alain Billier. The official version of the euro sign’s creation is disputed by Arthur Eisenmenger, a former leading graphic designer for the EEC, who claims to have created the sign as a common symbol for Europe.

According to the European Commission, this symbol is “a combination of the Greek letter ‘upsilon’, representing the importance of European civilization, the letter ‘E’ (for ‘Europe’) and parallel lines in the form of an equal sign, representing the stability of the euro.”

In addition, the European Commission calculated the exact dimensions of the euro logo, indicating the colors of the background and the sign itself. Although the Commission insisted on this particular spelling of the symbol, most of the designers have made it clear that they plan to create their own versions.

Placement of the graphic image of the currency in all countries is different. There are no official standards for the location of the euro sign.

There are no official standards for the location of the euro sign.

Another benefit of the final character is that it can be easily typed on the keyboard by typing a capital “C”, pressing the spacebar and overlaying an “equals” sign.

Common Economic and Monetary Space

History (1990 – present)

General provisions for the euro in the European Union were established by the Maastricht Treaty 1992 years to create economic and monetary unity. In order to switch to a new currency, EU countries had to meet strict criteria. For example, the country’s budget deficit should not exceed three percent of GDP, the debt ratio should be less than 6 percent of GDP, low inflation and interest rates close to the EU average should be observed. Under the Maastricht Treaty, Great Britain and Denmark received an exemption from the transition to a single monetary area, which led to the creation of the euro.

Economists involved in the creation of the euro – Robert Mundell, Wim Duesenberg, Robert Tollison, Neil Dowling, Fred Arditti and Tomaso Padoa-Schiopa (Macroeconomic theory, see below. )

)

Due to differences in national exchange rates, all calculations between national currencies were to be carried out through conversion to euro. The exact value of these currencies in euros (at the exchange rates at the time of the introduction of the euro) is shown to the right.

The exchange rates were determined by the Council of the European Union based on the market rate as of December 31, 1998 years, so that one ecu was equal to one euro. (The European currency unit was the unit of account of the EU, it existed on the basis of the national currencies of the participating countries; the ecu was not an independent currency.) The pan-European agreement 2866/98 (EC) of December 31, 1998 established such exchange rates. This could not have happened earlier, because at that time the ecu was closely linked to the exchange rate of other currencies (especially the pound sterling).

The procedure for the final recalculation of the drachma into euros was carried out differently, since then the euro had already existed for two years. The conversion rate for the first eleven currencies was determined a couple of hours before the introduction of the euro, for the Greek drachma it was set a few months earlier, under agreement 1478/2000 (EC) dated 19June 2000

The conversion rate for the first eleven currencies was determined a couple of hours before the introduction of the euro, for the Greek drachma it was set a few months earlier, under agreement 1478/2000 (EC) dated 19June 2000

On the night of January 1, 1999, the introduction of the euro into non-cash payments (traveler’s checks, electronic transfers, banking operations, etc.) took place. When the national currencies of the countries in the Eurozone ceased to exist separately, their exchange rates were fixed relative to each other, practically making them simple non-decimal parts of the euro. So the euro became a replacement for the ecu. However, banknotes and coins of the old currencies remained in circulation as legal tender until the issuance of new banknotes and coins in January 2002.

The replacement period, during which old banknotes and coins were exchanged for the euro, lasted about two months, until February 28, 2002. The official date for the end of the use of national currencies as legal tender differed from country to country. The very first country was Germany. On December 31, 2001, the stamp officially ceased to be used, although the exchange period lasted for another two months. February 28, 2002 is the end date of the replacement, when all national currencies ceased to be legal means of payment in the countries of the Eurozone. However, even after the official date, all currencies continued to be accepted in the state central banks of European countries with a restriction of several years or no restrictions at all, for example, in Austria, Germany, Ireland and Spain. The very first coins to go out of circulation were the Portuguese escudos, which depreciated after December 31, 2002, although banknotes are subject to exchange until 2022.

The very first country was Germany. On December 31, 2001, the stamp officially ceased to be used, although the exchange period lasted for another two months. February 28, 2002 is the end date of the replacement, when all national currencies ceased to be legal means of payment in the countries of the Eurozone. However, even after the official date, all currencies continued to be accepted in the state central banks of European countries with a restriction of several years or no restrictions at all, for example, in Austria, Germany, Ireland and Spain. The very first coins to go out of circulation were the Portuguese escudos, which depreciated after December 31, 2002, although banknotes are subject to exchange until 2022.

Slovenia joined the Eurozone on January 1, 2007, followed by Malta and Cyprus on January 1, 2008.

Eurozone

- The euro is the official currency in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain.

These 15 countries together make up the Eurozone or the euro area. Less officially, it is also called “Euroland” or “Eurogroup”. In addition to these territories, the geography of the euro as the official currency also extends to the colonies: French Guiana, Reunion, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Bartholomew, Saint Martin, Mayotte and the uninhabited island of Clipperton, French Southern and Antarctic Territories; Portuguese Autonomous Regions Azores and Madeira; Spanish Canary Islands.

These 15 countries together make up the Eurozone or the euro area. Less officially, it is also called “Euroland” or “Eurogroup”. In addition to these territories, the geography of the euro as the official currency also extends to the colonies: French Guiana, Reunion, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Bartholomew, Saint Martin, Mayotte and the uninhabited island of Clipperton, French Southern and Antarctic Territories; Portuguese Autonomous Regions Azores and Madeira; Spanish Canary Islands. - Based on a bilateral agreement, the European microstates of Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City mint their own euro coins on behalf of the European Central Bank. However, they are severely limited in the total amount of coins they can issue.

- Andorra, Montenegro, the Republic of Kosovo, Akrotiri and Dhekelia adopted the euro as the official currency of investment and monetary transactions without participation in the European system of central banks and without the right to issue coins.

Andorra entered into the process of negotiating an agreement on the issuance of money in the same way as in the case of the microstates of Europe.

Andorra entered into the process of negotiating an agreement on the issuance of money in the same way as in the case of the microstates of Europe. - The currencies of several dominions and former colonies of EU states are dependent on the euro. Among them are French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna (CFA franc), Cape Verde, Comoros and fourteen states of Central and West Africa (CFA franc). See “Currencies Dependent on the Euro”.

- Even though the euro is not legal tender in Denmark and the UK, some stores in these countries accept the euro, especially international department stores in major cities and in shops in Northern Ireland, on the border with the Republic of Ireland, where the euro is the official currency. Also, the euro is widely accepted in Switzerland, even in government organizations such as the Swiss Railways.

Perspectives

Countries that joined the EU before 2004

With the accession of Greece in 2001 and until the enlargement of the EU in 2004, Denmark, Sweden and the UK were the only EU members to retain their national currencies. The situation for these three oldest member states was different from the new EU members; they did not have a clear timetable for the adoption of the euro:

The situation for these three oldest member states was different from the new EU members; they did not have a clear timetable for the adoption of the euro:

- Denmark rejected several points of the Maastricht Treaty after it failed to pass in a referendum. On September 28, 2000, another referendum on the euro was held in Denmark, ending with a 53.2% vote against joining the Eurozone. However, Danish politicians propose to resume discussion of the four controversial points. In addition, Denmark orients the krone against the euro (€1 = DKK 7.46038 ± 2.25%), as the krone remains under the control of the European Economic Community. Although Greenland and the Faroe Islands are not part of the European Union, they use the Danish krone (Faroese krone in Faroe) and therefore also depend on the EEC.

- Sweden: Sweden is obliged to adopt the euro under the “Agreement of 1994” when economic conditions suit it. Although other conditions are met, the krone never entered EEC II, preventing Sweden from joining.

In 2003, a popular referendum rejected joining the Eurozone and Sweden has no plans to accept the euro. The EU has made it clear that it is turning a blind eye to this by respecting the position of Sweden and recognizing Sweden “de facto”, but this does not apply to other countries that joined the EU from 2004 to 2007.

In 2003, a popular referendum rejected joining the Eurozone and Sweden has no plans to accept the euro. The EU has made it clear that it is turning a blind eye to this by respecting the position of Sweden and recognizing Sweden “de facto”, but this does not apply to other countries that joined the EU from 2004 to 2007. - The UK received a challenge to join the eurozone under the Maastricht Treaty and is not required to switch to the euro. Although the government tries to join the union by arguing that economic conditions meet all the requirements (meet the “five economic criteria”), this issue has never been put to a vote.

- The UK was forced to withdraw the pound sterling from the EEC (predecessor of the EEC II) on Black Wednesday (September 16, 1992) due to confusion between its parity and economic behavior, so the pound is not included in the EEC II.

Countries that joined the EU after 2004

Since 2008, nine more countries have joined the EU with their own currency; however, all of these countries are required to adopt the euro under an accession agreement. Some of these countries have already acceded to the exchange rate control mechanism of the European Economic Community, EEC II. They plan to join the Eurozone in the following order (EEC III):

Some of these countries have already acceded to the exchange rate control mechanism of the European Economic Community, EEC II. They plan to join the Eurozone in the following order (EEC III):

- January 1, 2009 – Slovakia

- January 1, 2010 – Lithuania

- January 1, 2011 – Estonia,

- January 1, 2012 or later – Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, Czech Republic, Poland and Romania.

The accession of Lithuania and Estonia, scheduled for January 1, 2007, has been postponed due to high inflation rates in these countries. Some of these currencies floated against the euro, while the rest were pegged unilaterally to the euro before joining EEC II. For more information, see the article “The Exchange Rate Mechanism of the European Economic Community, Exchange Rates Against the Euro and Selected Currencies Articles”.

Originally, the Czech Republic planned to join the EEC II as early as 2008 or 2009, but the current government has officially pushed back the date to 2010, stating that the country will not be able to meet the economic criteria before that date. The deadline has now been extended to 2012.

The deadline has now been extended to 2012.

Latvia also planned to join Erozona in 2008, but an inflation rate of over 11% resulted in a rejection as the country does not meet existing requirements under council rules. Now the government has officially postponed this event to January 1, 2012, although the head of the Latvian central bank believes that 2013 should be considered a more realistic date.

Poland’s finance minister expressed his belief that publicly announcing the date of Poland’s accession would be “the wrong tactic”.

Other sources cast doubt on the reality of the accession of the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Estonia even within these terms.

The fifth report on “Practical Preparations for Further Eurozone Enlargement” was presented on 16 July 2007, according to which only Cyprus, Malta (introduced the euro in January), Slovakia (2009) and Romania (2014) have officially set approximate dates for the transition to the euro.

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia have already completed the design of the front side of their future coins.

Currency of Spain | it’s… What is the Currency of Spain?

- For the EUR quarter of Rome, see World Fair Quarter .

Euro (currency sign – €, bank code: EUR ) – the official currency in 16 countries of the Eurozone (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Finland, France). The currency is also used in 9countries, 7 of which are European. Thus, the euro is the single currency for more than 320 million Europeans, and together with the territories of unofficial circulation, for 500 million people [1] . In December 2006, there were 610 billion euros in cash circulation, making this currency the holder of the highest total value of cash circulating in the world, ahead of the US dollar in this indicator.

Euro was introduced to the world financial markets as a settlement currency on 1999, and on January 1, 2002, banknotes and coins were introduced into cash circulation. The Euro replaced the European Currency Unit (ECU), which was used in the European Monetary System from 1979 to 1998, at a ratio of 1:1.

The Euro replaced the European Currency Unit (ECU), which was used in the European Monetary System from 1979 to 1998, at a ratio of 1:1.

The 90,002 Euro is managed and administered by the European Central Bank (ECB) based in Frankfurt and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which consists of the central banks of the member countries of the Eurozone. The ECB is an independent central bank and has the exclusive right to determine monetary policy in the Eurozone. The ESCB is engaged in printing banknotes and minting coins, distributing cash among the countries of the Eurozone, and also ensures the functioning of payment systems in the Eurozone.

All members of the European Union are eligible to join the Eurozone if they meet certain monetary policy requirements, and for all new members of the European Union, the obligation to adopt the euro sooner or later is a sine qua non for membership.

Contents

|

Features Euro

Title

The name is written in Latin as Euro (with an uppercase or lowercase letter – differently in different languages), in Greek – ευρώ , Cyrillic spelling (in Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian and Serbian) – euro (in Montenegro variant euro is used). On banknotes, the name of the currency is indicated in capital Latin and Greek letters. The name is read in accordance with the spelling of specific languages, mainly following the pattern of how the word 9 is pronounced in that language0281 Europe : French approximately Euro , German Euro , Spanish Euro , English Euro etc.

The name is read in accordance with the spelling of specific languages, mainly following the pattern of how the word 9 is pronounced in that language0281 Europe : French approximately Euro , German Euro , Spanish Euro , English Euro etc.

In Russian, the rendering of this word as euro prevails, although dictionaries also give the variant euro [2] . According to normative dictionaries, this word is masculine, although in colloquial speech there is both a middle and (very rarely) feminine gender.

In connection with its forthcoming entry into the Eurozone, Bulgaria has raised the issue that banknotes should also bear the Cyrillic version of the currency name. The ECB opposed such an initiative [3] , however, in 2007 he was forced to agree with Bulgaria, however, stipulating that the word “euro” on banknotes would not change in numbers:

.

..Community legislation, taking into account the existence of different alphabets, requires the uniform spelling of the word “euro” in the nominative case and singular in all official documents of the Community and Member States [4]

Original text (eng.)

…Community law requires a single spelling of the word “euro” in the nominative singular case in all Community and national legislative provisions, taking into account the existence of different alphabets.

Coins and banknotes

Main articles : Euro coins , Euro banknotes

Euro consists of 100 cents (sometimes called eurocents ). All euro coins, including 2 euro commemorative coins, have one common side, on which the denomination of the coin is indicated against the background of the image of 16 countries of the Eurozone. On the other, “national” side, there is an image chosen by the country in which the coin was minted. All coins can be used in all countries where the euro has been adopted as the official currency.

All coins can be used in all countries where the euro has been adopted as the official currency.

Euro coins are issued in denominations of €2, €1, €0.50, €0.20, €0.10, €0.05, €0.02 and €0.01. Many shops in the Eurozone prefer to equalize prices so that they are multiples of 5 cents, for example in Finland, and 1 and 2 euro cent coins were not needed; in Austria, on the other hand, the 1 cent coin is very common.

All euro banknotes have a common design for each denomination on both sides in all countries. Banknotes are issued in denominations of €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10 and €5. Some higher denominations, such as the €500 and €200, are not issued in some countries but are legal tender everywhere.

| Nominal | Dimensions Weight | Style | Epoch | Location code | Basic color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Euro | 120 × 62 mm 0.63 g | Antiquity / Classic | Until the 11th century | left at the edge of the picture | gray |

| 10 Euro | 127 × 67 mm 0.  72 g 72 g | Romanesque | XI-XII centuries | star at 8 o’clock | red |

| 20 Euro | 133 × 72 mm 0.81 g | Gothic | XIII-XIV century | star at 9 o’clock | blue |

| 50 Euro | 140 × 77 mm 0.92 g | Renaissance | XV-XVI century | right at the edge of the picture | orange |

| 100 Euro | 147 × 82 mm 1.02 g | Baroque and Rococo | XVII-XVIII centuries | to the right of the star at 9 o’clock | green |

| 200 Euro | 153 × 82 mm 1.07 g | Industrial era / Iron and glass | 19th century | to the right of the star at 8 o’clock | tan |

| EUR 500 | 160 × 82 mm 1.12 g | Modernity | XX—XXI century | star at 9 o’clock | purple |

The ECB has established a clearing system for large payment transactions in euros (TARGET). All money transfers within Eurozone countries should cost the same as transfers within the same country. This is also true for retail payments, although different payment methods may be used. Payments with credit cards and withdrawals from ATMs also cost the same in all countries as in the country where the card was issued. Settlements using “paper” payment orders, such as checks, are not standardized by the ECB and are handled separately by each country.

All money transfers within Eurozone countries should cost the same as transfers within the same country. This is also true for retail payments, although different payment methods may be used. Payments with credit cards and withdrawals from ATMs also cost the same in all countries as in the country where the card was issued. Settlements using “paper” payment orders, such as checks, are not standardized by the ECB and are handled separately by each country.

Graphic euro sign (€)

Main article : Euro graphic

Official specification for the euro logo to be printed in yellow on a blue background (PMS Yellow and PMS Reflex Blue respectively)

A special graphic euro sign (€) was designed after two options out of ten proposals were selected through public opinion polls, and then the European Commission selected one of them as the final option. The winning design was allegedly created by a team of four experts who have not been officially named. The official version of the creation of the euro design is disputed by Arthur Eisenmenger [5] , formerly a leading European Community graphic designer who claims to have created this sign as a common symbol for Europe.

The official version of the creation of the euro design is disputed by Arthur Eisenmenger [5] , formerly a leading European Community graphic designer who claims to have created this sign as a common symbol for Europe.

The sign is, according to the European Commission, “ a combination of the Greek epsilon, as an indicator of the importance of European civilization, the letter E, denoting Europe, and the parallel lines crossing the sign, denoting the stability of the euro .” Because of these two lines, the graphic euro sign turned out to be significantly similar to the “Yes” symbol from the Slavic alphabet “round Glagolitic”.

The European Commission has also designed the euro logo with exact proportions and foreground and background colors [6] . Although some font designers have simply copied the euro logo exactly as the euro sign in these fonts, most have developed their own variations, which are often based on the letter C in the corresponding font, so that the currency sign has the same width as the Arabic numerals [7] .

The location of the graphic symbol in relation to the figures denoting the denomination of the currency differs from country to country. Although it is officially recommended to place the sign before the numbers (contrary to the general ISO recommendation to place the unit of measure after the number), in many countries the euro sign is placed in the same way as was customary for national currencies that preceded the euro.

Putting into circulation

In non-cash payments, euros were introduced from January 1, 1999; in cash since January 1, 2002. Euro cash has replaced the national currencies of 16 (out of 27) countries of the European Union.

In Sweden and Denmark, referendums were held in which the majority voted against the adoption of the euro. The UK also decided not to replace the national currency. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania planned to switch to the euro in 2009, but due to economic difficulties, this transition had to be postponed for at least 3 years. Bulgaria and Hungary plan to adopt the euro by 2010, the Czech Republic and Poland by 2011, and Romania by 2014.

Bulgaria and Hungary plan to adopt the euro by 2010, the Czech Republic and Poland by 2011, and Romania by 2014.

Andorra Bulgaria E.S. Eurozone ERM II members Self-bridge adaptation Other EU members Spec. adaptation agreement |

| Country | Old currency | Transition date | Exchange rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eurozone | |||

| Austria | Austrian schilling | January 1, 1999 1 | 13.7603 ATS |

| Belgium | Belgian franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 40.3399 BEF |

| Germany | DM | January 1, 1999 1 | 1.95583 DEM |

| Ireland | Irish pound | January 1, 1999 1 | 0. 787564 IEP 787564 IEP |

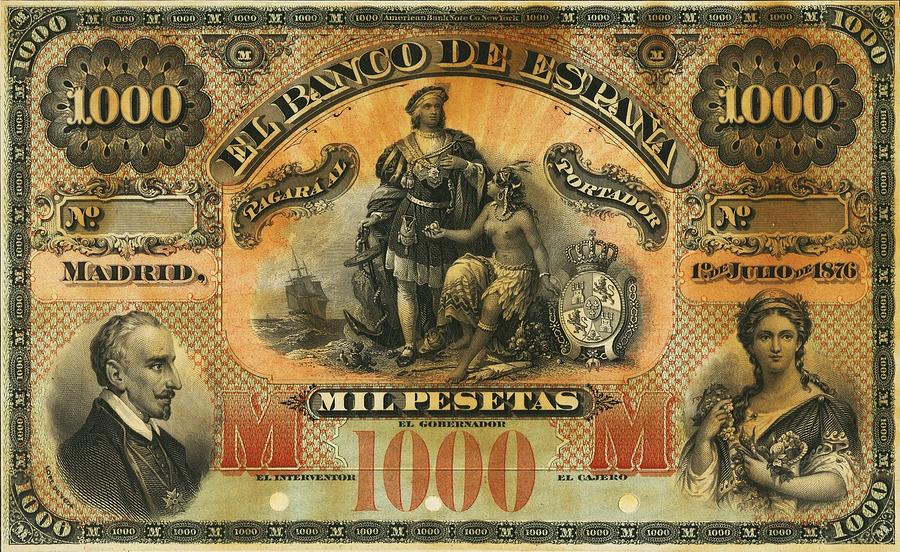

| Spain | spanish peseta | January 1, 1999 1 | 166.386 ESP |

| Italy | Italian Lira Vatican Lira sanmarine lira | January 1, 1999 1 | 1936.27 ITL |

| Luxembourg | Belgian franc Luxembourg franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 40.3399 LUF |

| Netherlands | Dutch guilder | January 1, 1999 1 | 2.20371 NLG |

| Portugal | Portuguese escudo | January 1, 1999 1 | 200.482 PTE |

| Finland | Finnish stamp | January 1, 1999 1 | 5.94573 FIM |

| France | French franc Monegasque franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 6. 55957 FRF 55957 FRF |

| Greece | Greek drachma | January 1, 2001 1 | 340.750 GRD |

| Slovenia | Slovenian tolar | January 1, 2007 | 239.640 SLT |

| Cyprus | Cypriot pound | January 1, 2008 | 0.585274 CYP |

| Malta | Maltese Lira | January 1, 2008 | 0.429300 MTL |

| Slovakia | Slovak koruna | January 1, 2009 | 30.1260 SKK |

| Non-EU countries, but officially using the euro according to agreements with the European Central Bank | |||

| Vatican | Italian lira Vatican lira Sanmarine lira | January 1, 1999 1 | 1936.27 VAL |

| Mayotte | French franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 6. 55957 FRF 55957 FRF |

| Monaco | French franc Monegasque franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 6.55957 MCF |

| San Marino | Italian lira Vatican lira Sanmarine lira | January 1, 1999 1 | 1936.27 SML |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | French franc | January 1, 1999 1 | 6.55957 FRF |

| Countries and territories informally using the euro | |||

| Akrotiri and Dhekelia | Cypriot pound | January 1, 2008 | 0.585274 CYP |

| Andorra | French franc Spanish peseta | January 1, 1999 1 | 6.55957 FRF 166.386 ESP |

| Kosovo | DM | January 1, 2002 | 1.95583 DEM |

| Saint Barthelemy | French franc | January 1, 1999 1. 2 2 | 6.55957 FRF |

| Saint Martin | French franc | January 1, 1999 1.2 | 6.55957 FRF |

| Montenegro | DM | January 1, 2002 | 1.95583 DEM |

1 Actual January 1, 2002

2 Separated on February 22, 2007 from the French overseas department of Guadeloupe

Effects of the introduction of a single currency

Euro monument in Frankfurt

The use of a single currency in many countries has both advantages and disadvantages for member countries. By now, there are different opinions about the effects caused by the introduction of the euro, since it will take many years to understand and evaluate many of these effects. There are many theories and predictions.

Dealing with exchange rate risks

One of the most important advantages of the euro is the reduction of risks associated with exchange rates, which makes it easier to invest between countries. The risk of currency fluctuations against each other has always made investments outside of its currency area, and even import / export, very risky for both companies and individuals. Possible profits can be instantly reduced to zero by fluctuations in the exchange rate. As a result, many investors and importers/exporters have had to either accept this risk or hedge their investments, further pushing up prices in the financial markets. Investments outside the national currency area are therefore less attractive. The creation of the Eurozone greatly increases the scope for investment, free from exchange rate risks. Since the European economy is heavily dependent on intra-European exports, the benefits of this effect cannot be overestimated. In particular, it is very important for countries whose national currencies have traditionally been subject to strong exchange rate fluctuations (for example, the Mediterranean states).

The risk of currency fluctuations against each other has always made investments outside of its currency area, and even import / export, very risky for both companies and individuals. Possible profits can be instantly reduced to zero by fluctuations in the exchange rate. As a result, many investors and importers/exporters have had to either accept this risk or hedge their investments, further pushing up prices in the financial markets. Investments outside the national currency area are therefore less attractive. The creation of the Eurozone greatly increases the scope for investment, free from exchange rate risks. Since the European economy is heavily dependent on intra-European exports, the benefits of this effect cannot be overestimated. In particular, it is very important for countries whose national currencies have traditionally been subject to strong exchange rate fluctuations (for example, the Mediterranean states).

At the same time, it is highly likely that such an effect will increase investment in countries with more liberal markets and decrease it where markets are more strict. Some people are worried that profits will flow to neighboring countries, and because of this, traditional social programs will have to be cut.

Some people are worried that profits will flow to neighboring countries, and because of this, traditional social programs will have to be cut.

Elimination of costs associated with conversion transactions

With the introduction of the single currency, fees charged by banks for the transfer of funds from one currency to another, which were previously charged both from individuals and commercial organizations, are eliminated. Although the savings from this for each transaction are small, given the many thousands of transactions made, it provides a significant increase in the funds circulating in the European economy.

For electronic payments (credit cards, debit cards and ATMs), banks in the Eurozone must currently charge the same fees for cross-border payments in the Eurozone as for payments within one country. France’s banks got around this rule by imposing fees on all transactions (national and international) except those made using online banking, a method that is not available for international payments. Thus, French banks actually continue to charge higher fees for international transactions than for national ones.

Thus, French banks actually continue to charge higher fees for international transactions than for national ones.

More stable financial markets

Another notable benefit of adopting the euro is the creation of more stable financial markets. Financial markets on the European continent are expected to become much more liquid and flexible than they have been in the past. There will be more competition and financial products will be more accessible across the EU. This will reduce the cost of financial transactions for businesses and perhaps even for individuals across the continent. The cost of servicing public debt will also fall. It is expected that the emergence of more stable and wider markets will lead to an increase in the capitalization of the equity market and increase investment. Larger and internationally competitive financial institutions may emerge.

Price parity

Another effect of the introduction of a single European currency is that the difference in prices – in particular, in the price level – should decrease. Price differences can provoke arbitrage, that is, speculative trade in goods between countries just to exploit price differences. The introduction of a single currency equalizes prices in the Eurozone, and the result is expected to be increased competition or consolidation of companies, which should curb inflation and thus benefit consumers. Similarly, price transparency across borders should help consumers find a quality product or service at a low price.

Price differences can provoke arbitrage, that is, speculative trade in goods between countries just to exploit price differences. The introduction of a single currency equalizes prices in the Eurozone, and the result is expected to be increased competition or consolidation of companies, which should curb inflation and thus benefit consumers. Similarly, price transparency across borders should help consumers find a quality product or service at a low price.

In reality, the impact of the introduction of the euro on the price level in Europe is questioned. Many European citizens point to a significant increase in prices in the years following the introduction of the euro, although many empirical studies have failed to confirm this. It is assumed that the reason for this feeling is that the prices of small, everyday goods have been rounded up, and the difference is sometimes a significant amount. For example, a cup of coffee that cost two marks now costs one and a half or even two euros – the price has increased by 50-100%. At the same time, large payments for various technical devices or for housing increased slightly in percentage terms due to rounding up. The fact that the prices that people see every day are perceived more acutely may explain why so many people believe that prices have risen with the introduction of the euro, while official studies that look at many different items of expenditure do not find this. .

At the same time, large payments for various technical devices or for housing increased slightly in percentage terms due to rounding up. The fact that the prices that people see every day are perceived more acutely may explain why so many people believe that prices have risen with the introduction of the euro, while official studies that look at many different items of expenditure do not find this. .

Competitive refinancing

Competitive refinancing is also a virtue for many countries (and companies) that have entered the Eurozone. National and corporate bonds denominated in euros are much more liquid and have lower interest rates than they used to be when they were denominated in national currency. Companies also have more freedom to borrow money from banks abroad without exposing themselves to exchange rate risks. This forces national banks to lower interest rates in order to be competitive.

European national currencies pegged to the euro

Some countries have not yet become part of the Eurozone, but have created favorable conditions in their national economies for the “transition period” — they peg their currencies to the euro according to established ratios in the event of the expected transition to the euro, for example: Latvian lats, Lithuanian litas.

Some other currencies were originally pegged to the German mark (Bosnian mark (1:1), Bulgarian lev (1:1), Estonian krone (8:1)). After Germany’s adoption of the euro, the ratio of the pegging of these currencies to the euro was multiplied by the exchange rate of the German mark for the euro.

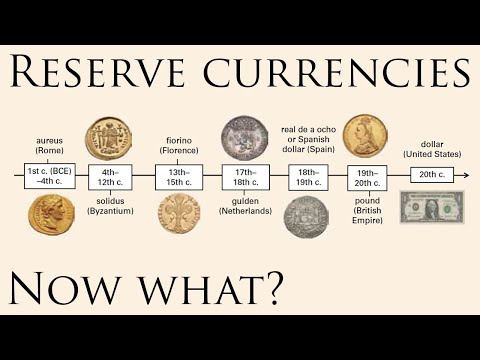

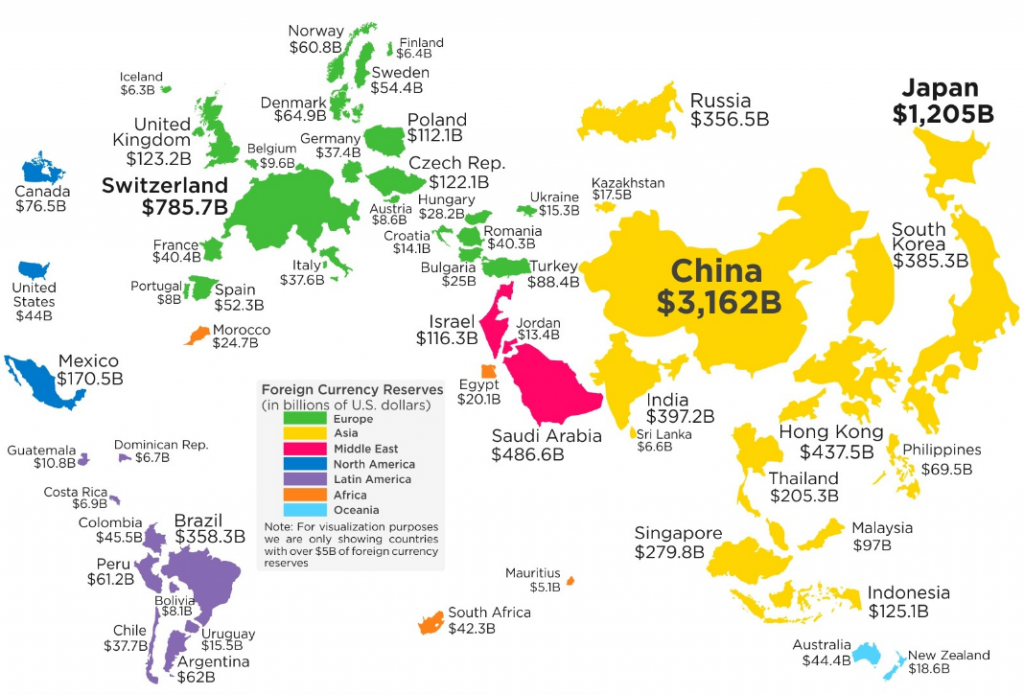

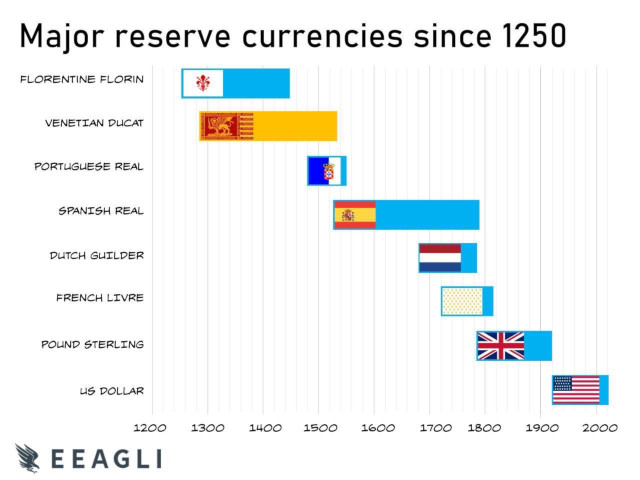

Euro as reserve currency

Euro is currently the second most used reserve currency. After the introduction of the Euro in 1999, this currency partially inherited a share in settlements and reserves from the German mark, French franc and other European currencies that were used for settlements and savings. Since then, the share of the euro has steadily increased as central banks seek to diversify their reserves. [8] Former Fed chief Alan Greenspan said in September 2007 that the euro could replace the US dollar as the world’s main reserve currency. [9]

| ’95 | ’96 | ’97 | ’98 | ’99 | ’00 | ’01 | ’02 | ’03 | ’04 | ’05 | ’06 | ’07 | ’08 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD | 59. 0% 0% | 62.1% | 65.2% | 69.3% | 70.9% | 70.5% | 70.7% | 66.5% | 65.8% | 65.9% | 66.4% | 65.7% | 64.1% | 64.0% |

| EUR | 17.9% | 18.8% | 19.8% | 24.2% | 25.3% | 24.9% | 24.3% | 25.2% | 26.3% | 26.5% | ||||

| DEM | 15.8% | 14.7% | 14.5% | 13.8% | ||||||||||

| GBP | 2. 1% 1% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 2.7% | 2.9% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.9% | 2.6% | 3.3% | 3.6% | 4.2% | 4.7% | 4.1% |

| YEN | 6.8% | 6.7% | 5.8% | 6.2% | 6.4% | 6.3% | 5.2% | 4.5% | 4.1% | 3.9% | 3.7% | 3.2% | 2.9% | 3.3% |

| FRF | 2.4% | 1.8% | 1. 4% 4% | 1.6% | ||||||||||

| CHF | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Other | 13.6% | 11.7% | 10.2% | 6.1% | 1.6% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 1.5% | 1. 8% 8% | 2.0% |

| Sources: 1995-2008 IMF (International Monetary Fund): : Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves Sources: 1999-2005, ECB (European Central Bank): The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves Sources: 2008 data are for the first half of the year p | ||||||||||||||

Interesting Facts

- One of the means of protection against forgery of the euro is the number on the banknote. The number itself consists of a letter and eleven digits. If you add up all the digits in the number, you get a two-digit number. Then, sequentially adding the digits that make up the number, you can get a single-digit number. For example, given the number 79, add 7 and 9, we get 16 – add 1 and 6, we get in the end – 7. This number, like the letter in the number, indicates the country in which the bill was made. It must correspond to the letter in the number, which is also assigned to this country.

For example, if the letter in the number is X (reserved for Germany), and the resulting number is not 2, then the bill is definitely fake. Another way: add up all the numbers that make up the number and add to them a number equal to the ordinal number of the letter in the English alphabet. Then, you should also add the numbers that make up the resulting number. The result should be the number 8. If the number is different from 8, then the bill is fake. [10]

For example, if the letter in the number is X (reserved for Germany), and the resulting number is not 2, then the bill is definitely fake. Another way: add up all the numbers that make up the number and add to them a number equal to the ordinal number of the letter in the English alphabet. Then, you should also add the numbers that make up the resulting number. The result should be the number 8. If the number is different from 8, then the bill is fake. [10] - It is interesting to note that on the day of his birth, the euro exchange rate against the US dollar started at 1.1750, and the absolute historical minimum of the rate was 0.8225. The absolute all-time high is 1.6037.

See also

- European currency unit

- European central banks and currencies

- 2 Euro commemorative coins

- Maastricht criteria

Notes

- ↑ This number is calculated as the sum of the inhabitants of all eurozone countries and non-eurozone countries that use the euro (not officially).

- ↑ http://dic.gramota.ru/search.php?word=%E5%E2%F0%EE&lop=x&efr=x&ag=x&zar=x

- ↑ Cyrillic inscription may appear on the euro (Russian). NEWSru.com (October 16, 2007). Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ↑ Convergence Report – May 2007. – The text cited in the quotation is in sec. 2.2.5 “Single spelling of the euro”. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ↑ http://observer.guardian.co.uk/print/0,3858,4325292-102275,00.html

- ↑ http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/euro/notes_and_coins/symbol_en.htm

- ↑ http://www.fontshop.com/virtual/features/eng/fontmag/002/02_euro/index.htm

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2006/wp06153.pdf

- ↑ http://www.reuters.com/article/bondsNews/idUSL1771147920070917 = | accessdate = September 17th | accessyear = 2007))

- ↑ How to tell real euros from fake ones

Links

- Catalog of euro coins in Russian in PDF format

- All about euro coins (including gold and silver)

- Euro coin catalog

- Euro coins.

These 15 countries together make up the Eurozone or the euro area. Less officially, it is also called “Euroland” or “Eurogroup”. In addition to these territories, the geography of the euro as the official currency also extends to the colonies: French Guiana, Reunion, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Bartholomew, Saint Martin, Mayotte and the uninhabited island of Clipperton, French Southern and Antarctic Territories; Portuguese Autonomous Regions Azores and Madeira; Spanish Canary Islands.

These 15 countries together make up the Eurozone or the euro area. Less officially, it is also called “Euroland” or “Eurogroup”. In addition to these territories, the geography of the euro as the official currency also extends to the colonies: French Guiana, Reunion, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Bartholomew, Saint Martin, Mayotte and the uninhabited island of Clipperton, French Southern and Antarctic Territories; Portuguese Autonomous Regions Azores and Madeira; Spanish Canary Islands. Andorra entered into the process of negotiating an agreement on the issuance of money in the same way as in the case of the microstates of Europe.

Andorra entered into the process of negotiating an agreement on the issuance of money in the same way as in the case of the microstates of Europe. In 2003, a popular referendum rejected joining the Eurozone and Sweden has no plans to accept the euro. The EU has made it clear that it is turning a blind eye to this by respecting the position of Sweden and recognizing Sweden “de facto”, but this does not apply to other countries that joined the EU from 2004 to 2007.

In 2003, a popular referendum rejected joining the Eurozone and Sweden has no plans to accept the euro. The EU has made it clear that it is turning a blind eye to this by respecting the position of Sweden and recognizing Sweden “de facto”, but this does not apply to other countries that joined the EU from 2004 to 2007. 1 Name

1 Name ..Community legislation, taking into account the existence of different alphabets, requires the uniform spelling of the word “euro” in the nominative case and singular in all official documents of the Community and Member States [4]

..Community legislation, taking into account the existence of different alphabets, requires the uniform spelling of the word “euro” in the nominative case and singular in all official documents of the Community and Member States [4]  For example, if the letter in the number is X (reserved for Germany), and the resulting number is not 2, then the bill is definitely fake. Another way: add up all the numbers that make up the number and add to them a number equal to the ordinal number of the letter in the English alphabet. Then, you should also add the numbers that make up the resulting number. The result should be the number 8. If the number is different from 8, then the bill is fake. [10]

For example, if the letter in the number is X (reserved for Germany), and the resulting number is not 2, then the bill is definitely fake. Another way: add up all the numbers that make up the number and add to them a number equal to the ordinal number of the letter in the English alphabet. Then, you should also add the numbers that make up the resulting number. The result should be the number 8. If the number is different from 8, then the bill is fake. [10]