Who were the tainos: Taíno: Indigenous Caribbeans – Black History Month 2022

Taíno: Indigenous Caribbeans – Black History Month 2022

The Taíno were an Arawak people who were the indigenous people of the Caribbean and Florida. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the principal inhabitants of most of Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic and Haiti), and Puerto Rico.

In the Greater Antilles, the northern Lesser Antilles, and the Bahamas, they were known as the Lucayans and spoke the Taíno language, a derivative of the the Arawakan languages.

The ancestors of the Taíno entered the Caribbean from South America. At the time of contact, the Taíno were divided into three broad groups, known as the Western Taíno (Jamaica, most of Cuba, and the Bahamas), the Classic Taíno (Hispaniola and Puerto Rico) and the Eastern Taíno (northern Lesser Antilles). A fourth, lesser known group went on to travel to Florida and divided into tribes. At present, we know there are four named tribes; the Tequesta, Calusa, Jaega and Ais. Other tribes are known to have settled in Florida, but their names are not known.

Other tribes are known to have settled in Florida, but their names are not known.

At the time of Columbus’ arrival in 1492, there were five Taíno chiefdoms and territories on Hispaniola, each led by a principal Cacique (chieftain), to whom tribute was paid. Ayiti (“land of high mountains”) was the indigenous Taíno name for the mountainous side of the island of Hispaniola, which has retained its name as Haïti in French.

Cuba, the largest island of the Antilles, was originally divided into 29 chiefdoms. Most of the native settlements later became the site of Spanish colonial cities retaining the original Taíno names. For instance; Havana,Batabanó, Camagüey, Baracoa and Bayamo are still recognised by their Taino names.

Puerto Rico also was divided into chiefdoms. As the hereditary head chief of Taíno tribes, the cacique was paid significant tribute. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the largest Taíno population centers may have contained over 3,000 people each.

The Taíno were historically enemies of the neighbouring Carib tribes, another group with origins in South America, who lived principally in the Lesser Antilles. The relationship between the two groups has been the subject of much study. For much of the 15th century, the Taíno tribe was being driven to the northeast in the Caribbean and out of what is now South America, because of raids by the Carib, resulting in Women being taken in raids and many Carib women speaking Taíno.

The Spaniards, who first arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico, did not bring women in the first expeditions. They took Taíno women for their common-law wives, resulting in mestizo children. Sexual violence in Hispaniola with the Taíno women by the Spanish was also common. Scholars suggest there was substantial racial and cultural mixing in Cuba, as well, and several Indian pueblos survived into the 19th century.

The Taíno became nearly extinct as a culture following settlement by Spanish colonists, primarily due to infectious diseases to which they had no immunity. The first recorded smallpox outbreak in Hispaniola occurred in December 1518 or January 1519. The 1518 smallpox epidemic killed 90% of the natives who had not already perished. Warfare and harsh enslavement by the colonists had also caused many deaths. By 1548, the native population had declined to fewer than 500. Starting in about 1840, there have been attempts to create a quasi-indigenous Taino identity in rural areas of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. This trend accelerated among the Puerto Rican community in the United States in the 1960s.

The first recorded smallpox outbreak in Hispaniola occurred in December 1518 or January 1519. The 1518 smallpox epidemic killed 90% of the natives who had not already perished. Warfare and harsh enslavement by the colonists had also caused many deaths. By 1548, the native population had declined to fewer than 500. Starting in about 1840, there have been attempts to create a quasi-indigenous Taino identity in rural areas of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. This trend accelerated among the Puerto Rican community in the United States in the 1960s.

Terminology

The Taíno people, or Taíno culture, has been classified by some authorities as belonging to the Arawak, as their language was considered to belong to the Arawak language family, the languages of which were present throughout the Caribbean, and much of Central and South America.

The early ethnohistorian, Daniel Garrison Brinton, called the Taíno people the “Island Arawak”. Nevertheless, contemporary scholars have recognized that the Taíno had developed a distinct language and culture.

Modern historians, linguists and anthropologists now hold that the term Taíno should refer to all the Taíno/Arawak tribes except for the Caribs, who are not seen to belong to the same people. Linguists continue to debate whether the Carib language is an Arawakan dialect or creole language, or perhaps an individual language, with an Arawakan pidgin used for communication purposes.

Spaniards and Taíno

Columbus and his crew, landing on an island in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492, were the first Europeans to encounter the Taíno people. Columbus described the Taínos as a physically tall, well-proportioned people, with a noble and kind personality.

Columbus wrote:

They traded with us and gave us everything they had, with good will…they took great delight in pleasing us…They are very gentle and without knowledge of what is evil; nor do they murder or steal…Your highness may believe that in all the world there can be no better people…They love their neighbours as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing.

At this time, the neighbors of the Taíno were the Guanahatabeys in the western tip of Cuba, the Island-Caribs in the Lesser Antilles from Guadeloupe to Grenada, and the Timacua and Ais tribes of Florida. The Taíno called the island Guanahaní which Columbus renamed as San Salvador (Spanish for “Holy Savior”). Columbus called the Taíno “Indians”, a reference that has grown to encompass all the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere. A group of Taíno people accompanied Columbus on his return voyage back to Spain.

On Columbus’ second voyage, he began to require tribute from the Taíno in Hispaniola. According to Kirkpatrick Sale, each adult over 14 years of age was expected to deliver a hawks bell full of gold every three months, or when this was lacking, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton. If this tribute was not brought, the Spanish cut off the hands of the Taíno and left them to bleed to death. These cruel practices inspired many revolts by the Taíno and campaigns against the Spanish —some being successful, some not.

In 1511, several caciques in Puerto Rico, such as Agüeybaná II, Arasibo, Hayuya, Jumacao, Urayoán, Guarionex, and Orocobix, allied with the Carib and tried to oust the Spaniards. The revolt was suppressed by the Indio-Spanish forces of Governor Juan Ponce de León. Hatuey, a Taíno chieftain who had fled from Hispaniola to Cuba with 400 natives to unite the Cuban natives, was burned at the stake on February 2, 1512.

In Hispaniola, a Taíno chieftain named Enriquillo mobilized over 3,000 Taíno in a successful rebellion in the 1520s. These Taíno were accorded land and a charter from the royal administration. Despite the small Spanish military presence in the region, they often used diplomatic divisions and, with help from powerful native allies, controlled most of the region. In exchange for a seasonal salary, religious and language education, the Taíno were required to work for Spanish and Indian land owners. This system of labor was part of the ‘encomienda’- the strongest protecting the weak for the purpose of economic gain .

Modern Taino Heritage

Groups of people currently identify as Taíno, most notably among the Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, both on the islands and on United States mainland. The concept of the “living Taíno” has been proven in a census in 2002. Some scholars, such as Jalil Sued Badillo, an ethnohistorian at the University of Puerto Rico, assert that the official Spanish historical record speak of the disappearance of the Taínos, but survivors had descendants and intermarried with other ethnic groups. Recent research notes a high percentage of mixed or tri-racial ancestry among people in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, with those claiming Taíno ancestry also having Spanish and African ancestry.

Taino | History & Culture

Taino village

See all media

- Related Topics:

- Central American and northern Andean Indian

Arawak

See all related content →

Taino, Arawakan-speaking people who at the time of Christopher Columbus’s exploration inhabited what are now Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Once the most numerous indigenous people of the Caribbean, the Taino may have numbered one or two million at the time of the Spanish conquest in the late 15th century. They had long been on the defensive against the aggressive Carib people, who had conquered the Lesser Antilles to the east.

Once the most numerous indigenous people of the Caribbean, the Taino may have numbered one or two million at the time of the Spanish conquest in the late 15th century. They had long been on the defensive against the aggressive Carib people, who had conquered the Lesser Antilles to the east.

When they were first encountered by Europeans, the Taino practiced a high-yielding form of shifting agriculture to grow their staple foods, cassava and yams. They would burn the forest or scrub and then heap the ashes and soil into mounds that could be easily planted, tended, and irrigated. Corn (maize), beans, squash, tobacco, peanuts (groundnuts), and peppers were also grown, and wild plants were gathered. Birds, lizards, and small animals were hunted for food, the only domesticated animals being dogs and, occasionally, parrots used to decoy wild birds within range of hunters. Fish and shellfish were another important food source.

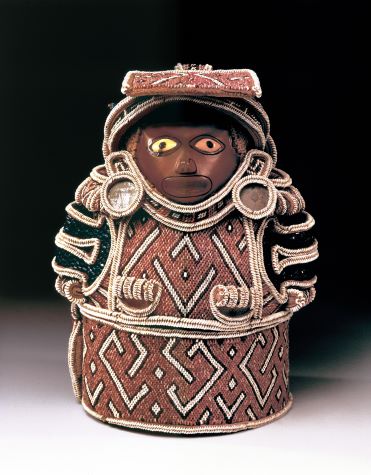

Traditional Taino settlements ranged from small family compounds to groups of 3,000 people. Houses were built of logs and poles with thatched roofs. Men wore loincloths and women wore aprons of cotton or palm fibres. Both sexes painted themselves on special occasions, and they wore earrings, nose rings, and necklaces, which were sometimes made of gold. The Taino also made pottery, baskets, and implements of stone and wood. A favourite form of recreation was a ball game played on rectangular courts. The Taino had an elaborate system of religious beliefs and rituals that involved the worship of spirits (zemis) by means of carved representations. They also had a complex social order, with a government of hereditary chiefs and subchiefs and classes of nobles, commoners, and slaves.

Houses were built of logs and poles with thatched roofs. Men wore loincloths and women wore aprons of cotton or palm fibres. Both sexes painted themselves on special occasions, and they wore earrings, nose rings, and necklaces, which were sometimes made of gold. The Taino also made pottery, baskets, and implements of stone and wood. A favourite form of recreation was a ball game played on rectangular courts. The Taino had an elaborate system of religious beliefs and rituals that involved the worship of spirits (zemis) by means of carved representations. They also had a complex social order, with a government of hereditary chiefs and subchiefs and classes of nobles, commoners, and slaves.

The Taino were easily conquered by the Spaniards beginning in 1493. Enslavement, starvation, and disease reduced them to a few thousand by 1520 and to near extinction by 1550. Those who survived mixed with Spaniards, Africans, and others. Taino culture was largely wiped out, although several groups claiming Taino descent gained visibility in the late 20th century, notably in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the U. S. state of Florida. In 1998 the United Confederation of Taino People, which characterizes itself as an “Inter-Tribal authority,” was created as an umbrella organization for the affirmation and restoration of Taino culture, language, and religion. Whereas the Taino are not officially recognized as a group by any governments, those who consider themselves Taino claim the right to self-determination.

S. state of Florida. In 1998 the United Confederation of Taino People, which characterizes itself as an “Inter-Tribal authority,” was created as an umbrella organization for the affirmation and restoration of Taino culture, language, and religion. Whereas the Taino are not officially recognized as a group by any governments, those who consider themselves Taino claim the right to self-determination.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaThis article was most recently revised and updated by Jeff Wallenfeldt.

Scientists have found that the Taino Indians did not die out

The Taino Indians who inhabited America before the arrival of Columbus did not die out, their descendants are modern Puerto Ricans, scientists have found out. Although Puerto Ricans themselves, like other descendants of the indigenous peoples of America, have repeatedly declared their belonging to the Taino, it has only now been possible to prove this.

When Columbus discovered America in 1492, he discovered that Haiti, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, Guadeloupe, the Bahamas and the Lesser Antilles were inhabited by many Taino tribes, Indians who arrived there around 1000 BC. e. After the Europeans began to develop new territories, the number of Tainos began to decline rapidly.

e. After the Europeans began to develop new territories, the number of Tainos began to decline rapidly.

The Catholic priest and historian of the time, Bartolome de Las Casas, wrote: “60,000 people lived on this island when I arrived in 1508, including the Indians;

thus from 1494 to 1508 more than three million people died from war, slavery and mines. Who in future generations will believe this?”

Many Americans, especially the Puerto Ricans, claimed to be descended from the Taíno and tried to gain recognition as a tribe. For these purposes, special organizations were created. Until now, it was believed that the Taino Indians died out, but the question of whether this was so was raised repeatedly. Studies of the genomes of modern Americans have suggested that they may be distant descendants of the Taíno. However, there have been no studies that would have analyzed the genome of the ancient Taino so far.

In a gigantic cave on Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas, an international team of archaeologists have unearthed the remains of the ancient Lukayo, a native of the Bahamas, a branch of the Taíno. One of the discovered skeletons belonged to a woman who lived in the 8th-10th centuries AD. BC, and there was enough DNA in her tooth to recreate her genome.

One of the discovered skeletons belonged to a woman who lived in the 8th-10th centuries AD. BC, and there was enough DNA in her tooth to recreate her genome.

close

100%

Next, the researchers compared it with the genomes of more than 40 modern Native American groups. The analysis showed that genetically the woman was connected with many modern peoples of North America. However, her closest genetic connection turned out to be with modern Puerto Ricans. The results of analyzes were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We found that the genomes of modern Puerto Ricans are closely related to those of the ancient Tainos. This demonstrates the continuity between pre-Columbian populations and modern Hispanics, despite the devastating effects of colonization,”

, the scientists say.

“This is an exciting discovery,” says archaeologist Hannes Schröder of the University of Copenhagen. “You can read in many history books that the indigenous population of the Caribbean was almost wiped out, but people who identify themselves as Taíno have always tried to dispute that. Now we know they were right all along.”

Now we know they were right all along.”

“It has always been clear that the people of the Caribbean are descendants of Native Americans, but due to the complex history of migration in the region, it has so far been difficult to prove this,” says Professor Eske Willerslev.

The team is confident that further research will prove that other indigenous peoples of the Caribbean are not extinct.

“It’s a pity my grandmother is no longer alive. I’d like to show her evidence of what she already knew,

, says researcher and Taino gene carrier Jorge Estevez of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York. “The discovery shows that Taíno assimilation took place, but not extinction. I am sincerely grateful to the scientists. For us, the descendants of the Taino, this is a real liberation.”

“This ancient Taino woman is like a cousin to the ancestors of the people of Puerto Rico,” explains geneticist Maria Nieves-Colon. – You know what? These people have not disappeared. In fact, they are still here, inside of us.”

In fact, they are still here, inside of us.”

“Archaeological evidence has always suggested that many people who settled in the Caribbean came from South America and that they maintained social ties that extended far beyond the territory of residence. Previously, it was problematic to prove this due to poorly preserved DNA samples, but this study shows that it is still possible to obtain the genome of the ancient inhabitants of the Caribbean, and this opens up exciting opportunities for new research, ”says Professor Corinne Hofmann from the University of Leiden.

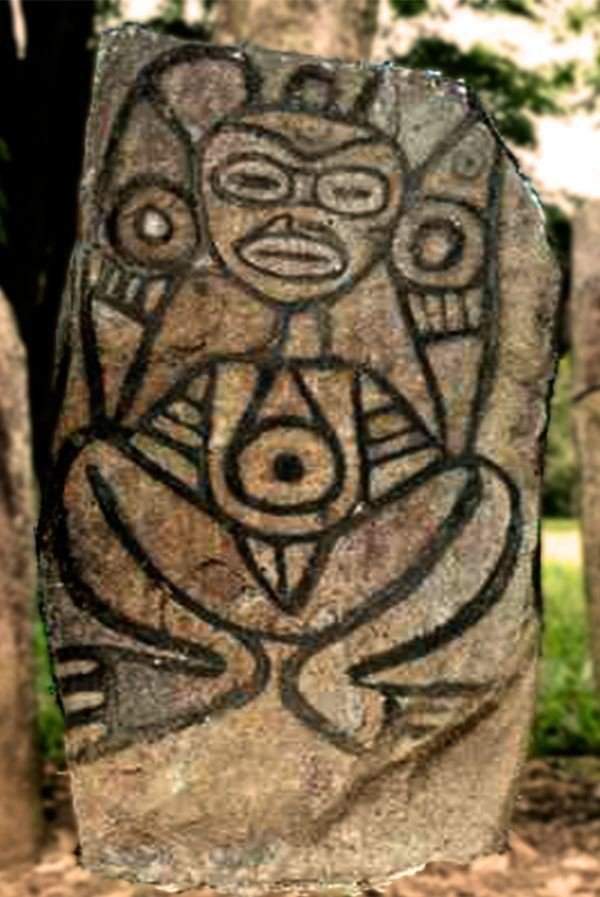

Previously, on the small island of Mona, located between the islands of Haiti and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, archaeologists discovered thousands of previously unknown ancient drawings in 70 hard-to-reach caves. With the help of radiocarbon dating, scientists were able to estimate the age of the cave drawings – it turned out that they were all created in the 14-15th centuries.

They were made from the excrement of bats which, over time, absorbed yellow, brown and red naturally occurring minerals on cave ceilings.

Sometimes wood resin was added to the paints to make the drawings stick better to the walls. Some of the drawings were made using charcoal, the scientists found. However, the vast majority of rock inscriptions were made by their authors simply by running their palms and fingers along the soft surface of the walls.

Many drawings impressed scientists with an unusual variety of forms and subjects, among them images of humans and animals intertwined with various abstract geometric figures are more common. %

Intricate geometric shapes, often flowing into each other geometric and anthropomorphic images, may indicate the use of hallucinogenic substances by their authors, the researchers say.

“For the millions of indigenous people who lived in the Caribbean region before the advent of Europeans, the caves were portals to the realm of the spiritual, and therefore these finds represent the essence of their belief system and components and cultural identity,” the scientists concluded.

Taíno (people) | it’s… What is the Taíno (people)?

Reconstruction of the Taino village in Cuba

Taíno (Spanish: Taíno ) is a Pre-Columbian Native American population of the Bahamas and the Greater Antilles, which includes Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, and Jamaica.

It was previously believed that the sailors Taino are related to the Arawaks of South America. Recent discoveries suggest a more likely origin for Taíno from the Andean tribes, in particular from Colla . Their language belongs to the Maipur languages spoken in South America and the Caribbean, which are part of the Arawakan language family. The Bahamian Taino were called the Lucayans (then the Bahamas were known as the Lucayan Islands).

Some researchers distinguish between Neo-Taino Cuba, Lucayans Bahamas, Jamaica and to a lesser extent Haiti and Quisqueia ( Quisqueya ) (approximately the territory of the Dominican Republic) and true Taíno Boriquen ( Boriquen ) (Puerto Rico). They consider this distinction important because Neo-Taino are characterized by greater cultural diversity and greater social and ethnic heterogeneity than the original Taino .

They consider this distinction important because Neo-Taino are characterized by greater cultural diversity and greater social and ethnic heterogeneity than the original Taino .

At the time of Columbus’s arrival in 1492, there were five “kingdoms” or territories in Hispaniola, each headed by a cacique (chief) to whom tribute was paid. During the Spanish conquests, the largest Taino settlements numbered up to 3 thousand people or more.

Historically the Tainos were neighbors and rivals of the Caribs, another group of tribes originating from South America, who mainly inhabited the Lesser Antilles. Much research has been devoted to the relationship between these two groups.

Tainos are said to have died out in the 17th century from imported diseases and forced assimilation into the plantation economy introduced by Spain in their Caribbean colonies, followed by the importation of slaves from Africa. However, the main reason for the disappearance of this culture was the massacre carried out by the Spaniards. It is claimed that there was a significant miscegenation, and that a few Indian pueblos survived until the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first landed in the Bahamas, Cuba and Hispaniola in 1492, and then to Puerto Rico, did not bring women with them. They entered into a civil marriage with women Taino . From these marriages, mestizo children were born. [1]

It is claimed that there was a significant miscegenation, and that a few Indian pueblos survived until the 19th century in Cuba. The Spaniards who first landed in the Bahamas, Cuba and Hispaniola in 1492, and then to Puerto Rico, did not bring women with them. They entered into a civil marriage with women Taino . From these marriages, mestizo children were born. [1]

Contents

|

Origin

There is a point of view that Taino came to the Caribbean through Guyana and Venezuela to Trinidad, subsequently spreading north and west throughout the Antilles around 1000 BC. e., after the migration of the Siboneans. However, recent discoveries have shown that a more accurate hypothesis is their proximity to the ancient tribe colla in the Andes. The Taíno traded extensively with other tribes in Florida and Central America, where they sometimes had outposts, although there were no permanent settlements. The Caribs followed Taíno to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

e., after the migration of the Siboneans. However, recent discoveries have shown that a more accurate hypothesis is their proximity to the ancient tribe colla in the Andes. The Taíno traded extensively with other tribes in Florida and Central America, where they sometimes had outposts, although there were no permanent settlements. The Caribs followed Taíno to the Antilles c. 1000 AD where they displaced and assimilated the Igneri, the Arawak people of the Lesser Antilles. They were never able to gain a foothold in the Greater Antilles or in the very north of the Lesser Antilles.

Caribs originate from the population of the South American continent. Caribs are sometimes referred to as Arawak, although linguistic similarities may have developed over centuries of close contact between these groups, both before and after the migration to the Caribbean Islands (see below). In any case, there are enough differences in the socio-political organization between the Arawaks and the Caribs to classify them as different peoples.

Terminology

Acquaintance of Europeans with Taíno occurred in stages as they colonized the Caribbean. Columbus called the inhabitants of the northern islands Taíno , which in Arawak means “friendly people” in contrast to the hostile Caribs. This name covered all the insular Taino , which in the Lesser Antilles were often referred to by the name of a particular tribe Taino .

Other Europeans arriving in South America named the same ethnic group Arawakami according to the Arawak word for cassava (tapioca) flour, which was the staple food of this ethnic group. Over time, the ethnic group began to be called Arawak (eng. Arawak ), and the language was Arawak. Later it turned out that the culture and language, as well as the ethnicity of the people known as Arawak and Taino, were the same, and often among them were distinguished mainland Taino or mainland Arawak living in Guyana and Venezuela, island Taino or island the Arawaks, who inhabit the Windward Islands; and simply the Taíno, who live in the Greater Antilles and the Leeward Islands.

For a long time travelers, historians, linguists, anthropologists used these terms mixed. The word Taino sometimes denoted only the tribes of the Greater Antilles, sometimes they also included the tribes of the Bahamas, sometimes the Leeward Islands or all of them together, with the exception of the tribes of Puerto Rico and the Leeward Islands. The 90,061 Insular Tainos 90,062 included residents of only the Windward Islands, only the population of the northern part of the Caribbean, or residents of all islands. Currently, modern historians, linguists and anthropologists believe that the term “Taino” should refer to all the Taino / Arawak tribes, except for the Caribs. Neither anthropologists nor historians consider the Caribs to be the same ethnic group, although linguists still debate whether the Caribbean language is an Arawakan dialect or a Creole language, or perhaps a separate language, with Arawakan pidgin often used in communication.

Culture and lifestyle

In the middle of the model settlement Taino ( yukayek ) there was a flat area ( batei ) where social events took place: games, celebrations and public ceremonies. The site was surrounded by houses. Taino played a ceremonial ball game called batu. Teams of players (from 10 to 30 people each) participated in the game. The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

The site was surrounded by houses. Taino played a ceremonial ball game called batu. Teams of players (from 10 to 30 people each) participated in the game. The ball was made from molded rubber. Batu also served to resolve conflicts between communities.

In society Taino four main groups were distinguished:

- set (ordinary people)

- nitaino (junior chiefs)

- bohics (priests/physicians)

- caciques (chiefs)

Often the main population lived in large round huts ( bohio ) built of wooden poles, woven straw mats and palm leaves. These huts housed 10-15 families. The caciques with their families lived in rectangular buildings ( cane ) of a similar design with a wooden porch. From the furniture in the house there were cotton hammocks ( hamaka ), palm mats, wooden chairs ( duyo ) with wicker seats, scaffolds, baby cradles. Some tribes Taino practiced polygamy. Men could have 2 or 3 wives, sometimes women had 2 or 3 husbands, and caciques had up to 30 wives.

Men could have 2 or 3 wives, sometimes women had 2 or 3 husbands, and caciques had up to 30 wives.

Taino were mainly engaged in agriculture, as well as fishing and hunting. A common hairstyle was bangs in front and long hair in the back. Sometimes they wore gold jewelry, painted themselves, adorned themselves with shells. Sometimes men Taino wore short skirts. Women Taino wore skirts ( nagua ) after marriage.

Taíno spoke a variety of Arawakan and used the following words: barbacoa ( barbecue ), hamaka ( hammock ), canoa ( canoe ), tabaco ( tabac ) and huracan ( 90 6 entered Spanish, English and Russian.

Nutrition and agriculture

Power base Taino were vegetables, meat and fish. There was never a lot of big game on the islands, small animals were eaten: rodents, bats, earthworms, ducks, turtles, birds.

The Taino communities, which lived inland, relied more on agriculture. They cultivated their crops on konuko , large ridges that were compacted with leaves to prevent erosion and planted with different types of plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

They cultivated their crops on konuko , large ridges that were compacted with leaves to prevent erosion and planted with different types of plants. This was done to obtain a crop in any weather conditions. They used koa , an early variety of hoe made entirely of wood. One of the main crops cultivated by the Tainos was cassava, which they ate in the form of tortillas similar to Mexican tortillas. The Taino also grew maize, squash, legumes, capsicum, sweet potatoes, yams, peanuts, and tobacco.

Technology

The Taino made extensive use of cotton, hemp and palm trees for making fishing nets and ropes. Their hollowed-out canoes (canoas) varied in size and could carry from 2 to 150 people. A medium-sized canoa held about 15 to 20 people. The Taíno used bows and arrows and sometimes smeared arrowheads of various kinds with poisons. They used spears for fishing. For military purposes, they used wooden combat batons (clubs), which they called “macana” ( macana ) were about three centimeters thick and resembled cocomacaque .

Religion

The Taino revered all forms of life and recognized the importance of thanksgiving, as well as honoring ancestors and spirits, whom they called seven or zemi . [2] Many stone images seven have survived. Some stalagmites in the Dondon caves are hewn in the form of seven . Seven sometimes had the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, caimans, as well as various abstract and humanoid faces.

Some of the seven carved include a small table or tray on which is believed to have been placed a hallucinogenic concoction, the so-called cohoba, made from the beans of a species of the Anadenanthera tree (Anadenanthera). Such trays were found along with ornamented breathing tubes.

During some rituals the Taíno vomited with a swallowing stick. This was done with the aim of cleansing the body of impurities, both literal physical and symbolic spiritual cleansing. After the ritual of offering bread, first to the spirits seven , then the cacique, and then the ordinary members of the community, the epic song of the village was performed to the accompaniment of the maraka and other musical instruments.

Oral tradition Taino explains how the sun and moon came out of the caves. Another legend tells that people once lived in caves and came out of them only at night, because it was believed that the Sun would change them. The origin of the oceans is described in the legend of a giant flood that happened when a father killed his son (who was about to kill his father) and then put his bones in a gourd or calabash bottle. Then the bones turned into fish, the bottle broke and all the waters of the world poured out of it.

The supreme deity was called “yukahu” ( Yucahú ), which means “white yuca” or “spirit of yuca”, as the yuca was the main source of food for the Taíno and was revered as such.

Some anthropologists argue that some or all of the Petwo Voodoo rituals may be traced back to the Taíno religion.

Columbus and Taino

Christopher Columbus and his crew, who landed in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492, became the first Europeans to see the Taíno people. It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually encompassed all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

It was Columbus who called the Taino “Indians,” giving them a name that eventually encompassed all the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

There are discussions about the number of Tainos who inhabited Haiti when Columbus landed there in 1492. The Catholic priest and historian of that time, Bartolome de Las Casas, wrote (1561) in his multi-volume History of the Indies:

- “ There were 60,000 people on this island [when I arrived in 1508], including Indians; thus from 1494 to 1508 more than three million people died from war, slavery and mines. Who in future generations will believe this? ”

Today, a number of historians suggest that Las Casas’ figures for the pre-European population of the Taíno are exaggerated, and that a figure closer to one million seems more likely. Estimates of the Taino population vary greatly, ranging from a few hundred thousand to 8 million. They were not immune from European diseases, especially smallpox, but many of them were driven to their graves by overwork in the mines and fields, slaughtered in the brutal suppression of rebellions, or committed suicide to escape their cruel new masters. According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

According to some scholars, the population of Hispaniola dropped sharply to 60,000, and by 1531 to 3,000.

During Columbus’s second voyage, he began demanding tribute from the Tainos in Haiti. Each Taino adult over the age of 14 had to give a certain amount of gold. At an early stage, the conquests, in case of non-payment of tribute, either maimed him or executed him. Later, for fear of losing their labor force, they were ordered to hand in 11 kg of cotton each. This fear also led to a demand for a debugging called “ encomienda “. Under this system, the Taíno had to work for the Spaniard who owned the land for most of the year, leaving them little time to attend to the affairs of their community.

Colonization resistance

Taino heritage today

Many people still claim to be Taino descendants, especially among Puerto Ricans, both on the island itself and in the US mainland. People who claim to be descended from the Taino are actively trying to gain recognition for their tribe. More recently, a number of Taino organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taino People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” (). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

More recently, a number of Taino organizations have been formed for this purpose, such as the United Confederation of Taino People ( United Confederation of Taíno People ) and “The Jatibonicù Taíno Tribal Nation of Boriken (Puerto Rico)” (). What some see as the Taíno revitalization movement can be seen as an integral part of a broader process of revitalizing the self-identification and organization of Caribbean indigenous peoples. [3]

Lambda Sigma Upsilon, Latino Fraternity, Incorporated ) made the Taíno Indians their cultural icon. [4]

See also

- Indians

- Indian Genocide

Notes

- ↑ Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-Afro-European People and Culture on Hispaniola .

- ↑ (meaning)

- ↑ Indigenous resurgence in the contemporary Caribbean

- ↑ Lambda Sigma Upsilon

Literature

- Guitar, Lynne.