Islam in puerto rico: A peek into the lives of Puerto Rican Muslims and what Ramadan means post Hurricane Maria

A peek into the lives of Puerto Rican Muslims and what Ramadan means post Hurricane Maria

For Juan, Ramadan is a balancing act. On the one hand is his religious faith and practice. On the other is his land, his culture, his home: Puerto Rico.

Although he weaves these two elements of his identity together in many ways, during Ramadan, the borderline between them becomes palpable. For the Puerto Rican Muslims like Juan, the holy month of fasting brings to the surface the tensions they feel in their daily life as minorities – and as Muslims among their Puerto Rican family and Puerto Ricans in the Muslim community.

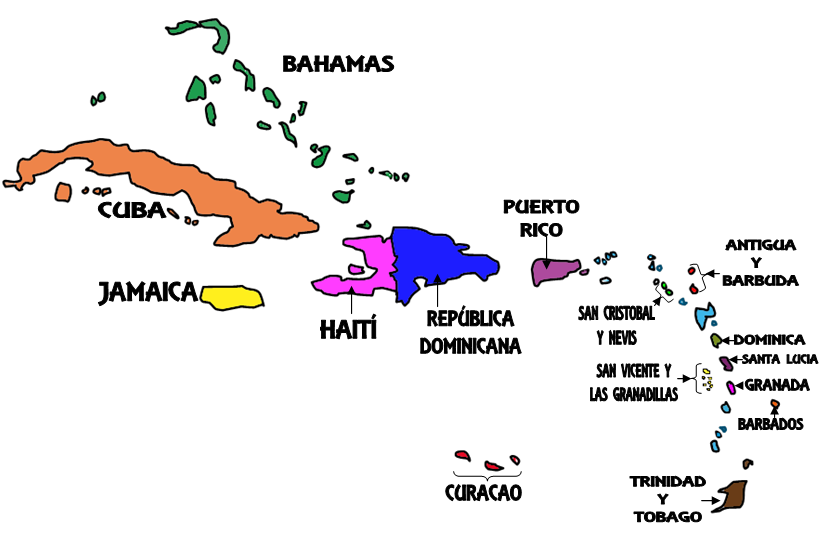

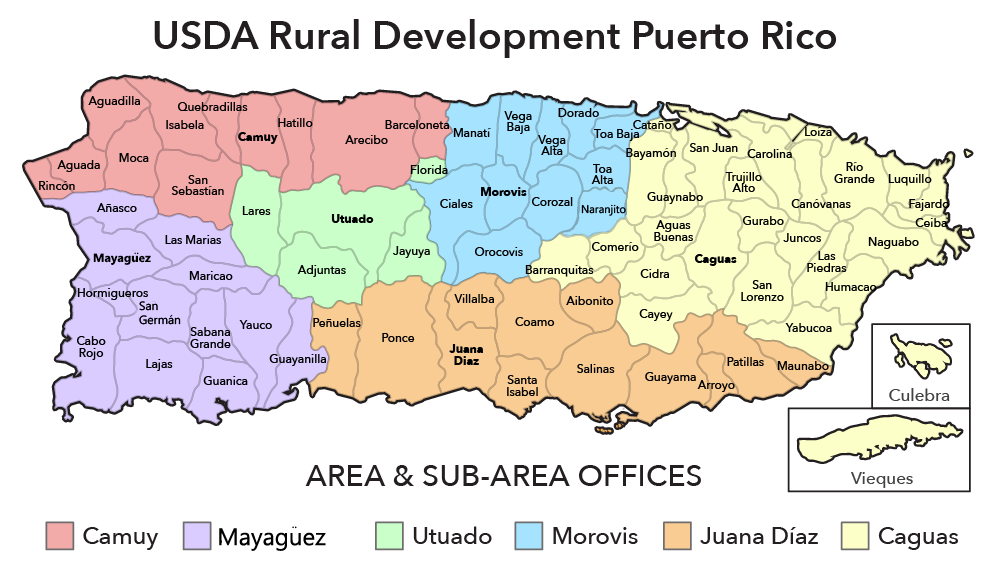

That is even more true this year in the wake of Hurricane Maria, the storm that made landfall in the southeastern city of Yabucoa on Sept. 20, 2017, and devastated parts of Puerto Rico. Even today, many parts of the island are without essential services, such as consistent electricity and water or access to schools.

I met Juan in 2015, when I first traveled to Puerto Rico in an effort to better understand the Puerto Rican Muslim story as part of my broader research on Islam in Latin America and the Caribbean. What I have found, in talking to Muslims in Puerto Rico and in many U.S. cities, is a deep history and a rich narrative that expands the understanding of what it means to be Muslim on the one hand, and, on the other, Puerto Rican. This Ramadan, Muslims in Puerto Rico are using the strength of both these identities to deal with the havoc of Hurricane Maria.

What I have found, in talking to Muslims in Puerto Rico and in many U.S. cities, is a deep history and a rich narrative that expands the understanding of what it means to be Muslim on the one hand, and, on the other, Puerto Rican. This Ramadan, Muslims in Puerto Rico are using the strength of both these identities to deal with the havoc of Hurricane Maria.

The history of Muslims in Puerto Rico

Muslims first came to the island as part of the transatlantic colonial exchange between Spain and Portugal and the “New World.” There is evidence that the first Muslims arrived with the explorers in the 16th century. Many “Moriscos,” or Iberian Muslims, came to the Caribbean bypassing several Spanish laws that prohibited them from coming to the Americas and served as merchants and explorers. Some were taken as slaves.

Enslaved Muslims from West Africa also came to the island beginning in the 16th century. While exact numbers are not known, scholars believe they were significant. These Muslim slave communities did not thrive, or even survive, but Islam established itself across the Western Hemisphere. It became the region’s “second monotheistic religion” thanks to Muslim slaves, former slaves and maroons – Africans who escaped slavery and founded independent settlements. These Muslims left their mark and contributed to the culture and history of the continents.

These Muslim slave communities did not thrive, or even survive, but Islam established itself across the Western Hemisphere. It became the region’s “second monotheistic religion” thanks to Muslim slaves, former slaves and maroons – Africans who escaped slavery and founded independent settlements. These Muslims left their mark and contributed to the culture and history of the continents.

Due to conversion to Catholicism or the adoption of Afro-American religious traditions such as Candomblé or Santería the influence and presence of Islam in the Americas faded over time. There is no evidence of direct links between present-day Muslim communities and the enslaved Muslims who came before.

Today’s Muslim communities largely comprise recent immigrants from Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt and Syria, with some descendants of the late 19th- and 20th-century immigrants. Ethnically speaking, nearly two-thirds of Puerto Rico’s Muslim population is made up of Palestinian immigrants, living in places like Caguas and San Juan, who came fleeing political turmoil or to pursue business interests.

Recent conversions

In recent years some Puerto Ricans have been reverting to the religion of their ancestors: Islam. In each of Puerto Rico’s nine mosques, researchers have found an increasing number of recent local converts. There is no accurate measure, but anecdotal evidence suggests rising numbers.

How do they wrestle with their identity as both Muslim and Puerto Rican?

Straddled between a predominately Arab Muslim population on the one hand and their avowedly Puerto Rican families, neighbors and co-workers who imagine Islam as a religion foreign to Puerto Rico, converts to Islam struggle to marry the two identities they now claim. They are in search of a “Boricua Islamidad” – a unique Puerto Rican Muslim identity that resists complete assimilation to Arab cultural norms even as it re-imagines and expands what it means to be Puerto Rican and a Muslim.

Puerto Rico Islamic Center at Ponce in Barrio Cuarto, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Roca Ruiz, CC BY-SA

When I first met Juan at an Eid al-Fitr celebration, the festival of breaking the Ramadan fast, at the San Juan Convention Center in 2015, the 40-something man said, “I came to Islam by asking questions: about the ills of society, the difficulties of life.”

For Juan, Catholicism, the religion adopted by his ancestors when they converted, was too confusing. The doctrine of “tawhid” in Islam – the oneness of God – was, as he saw it, simpler than what he believed to be the complex theology of the Trinity. Furthermore, he felt that Islam called for a higher morality and sense of self-discipline. And so, he “reverted” – that is, returned to the faith of his birth and the heritage of his Iberian forebears in al-Andalus, in what is modern-day Spain.

But Juan, like many other converts, is also searching for a sense of authenticity in his new community. While Juan finds that his Muslim brothers and sisters appreciate him, he still feels marginalized because of his cultural background. He finds ways to express his “Boricuan” (a term for resident Puerto Ricans, derived from the island’s indigenous name Borinquen) pride and his Muslim identity by sporting a “taqiyah,” a short, rounded skull cap, decorated with the Puerto Rican flag.

He finds ways to express his “Boricuan” (a term for resident Puerto Ricans, derived from the island’s indigenous name Borinquen) pride and his Muslim identity by sporting a “taqiyah,” a short, rounded skull cap, decorated with the Puerto Rican flag.

Another Puerto Rican convert from Aguadilla, Abu Livia, lives in this tension as well. He told me during an interview, “Too often we hear people say you have to wear certain clothes, speak a certain language, look like an Arab, talk like an Arab, behave like an Arab.”

Not just Juan and Abu Livia, as I found in my research, but many other Puerto Rican Muslims are looking toward Andalusia, or Moorish Spain, to search for their roots and define who they are in a Puerto Rican society that claims a mixed background of indigenous, African and European influences.

‘Puerto Rico se levanta’

Puerto Rican Muslims not only look across the Atlantic. They also look within themselves and are finding ways of expressing their Muslim faith through the symbols and struggles of Puerto Rican culture, whether it be their flag, their family traditions, or in how they respond to the trials of Hurricane Maria.

Following up with Juan after a year of struggle in the wake of the storm, he said, “Puerto Ricans are proud, committed, strong, and ‘pa’lante’ (moving forward). And that includes Muslims.” After the destruction of Hurricane Maria, the month of Ramadan, held special meaning for him. It held hope for “renewal.”

“‘Puerto Rico se levanta,’” he said, meaning Puerto Rico will rise, and “this Ramadan it will do so in the prayer, fasting, and charity of Muslims to help one another and their fellow Puerto Ricans prepare for a better future today and forever.”

For Juan, this is just another way his Puerto Rican identity helps him be a better Muslim. As he said, “We will fast this month, but we already know what it means to be in want.”

This incorporates elements of an earlier article published on June 23, 2017.

On Eid 2017, a peek into the lives of Puerto Rican Muslims

For Juan, Ramadan is a balancing act. On the one hand is his religious faith and practice. On the other is his land, his culture, his home – Puerto Rico.

On the other is his land, his culture, his home – Puerto Rico.

Although he weaves these two elements of his identity together in many ways, during Ramadan the borderline between them becomes palpable. For the 3,500 to 5,000 Puerto Rican Muslims like Juan, the holy month of fasting brings to the surface the tensions they feel in their daily life as minorities – Muslims among their Puerto Rican family and Puerto Ricans in the Muslim community.

So, who are the Puerto Rican Muslims and what are their struggles?

Since 2015, my broader research on Islam in Latin America and the Caribbean has taken me back and forth between Puerto Rico and cities in the U.S. where Puerto Rican Muslims live in large numbers (New York, New Jersey, Florida, Chicago, Atlanta, Houston and Philadelphia) in an effort to better understand the Puerto Rican Muslim story.

What I have found in my research is a deep history and a rich narrative that expands the understanding of what it means to be Muslim, and Puerto Rican, today.

The history of Muslims in Puerto Rico

Muslims first came to the island as part of the transatlantic colonial exchange between Spain and Portugal and the “New World.” There is evidence that the first Muslims arrived with the explorers in the 16th century. Many “Moriscos,” or Iberian Muslims, came to the Caribbean bypassing Spanish laws that prohibited them from coming to the Americas and serving as merchants, slaves and explorers.

Slaves from West Africa also came. Though these Muslim slave communities did not thrive, or even survive, Islam established itself in significant ways across the American hemisphere. It became the region’s “second monotheistic religion” – a result of the religious imagination and inventive ritualistic adaptation of Muslim slaves, former slaves and maroons – Africans who escaped slavery and founded independent settlements. These Muslims left their mark and contributed to the culture and history of the continents.

These slave communities, however, faded due to conversion to Catholicism or adoption of Afro-American religious practices. Today’s Muslim communities largely comprise recent immigrants from Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt and Syria; some are descendants of late 19th- and 20th-century immigrants. Ethnically speaking, nearly two-thirds of Puerto Rico’s Muslim population is made up of Palestinian immigrants living in places like Caguas and San Juan who came fleeing political turmoil or to pursue business interests abroad.

Today’s Muslim communities largely comprise recent immigrants from Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt and Syria; some are descendants of late 19th- and 20th-century immigrants. Ethnically speaking, nearly two-thirds of Puerto Rico’s Muslim population is made up of Palestinian immigrants living in places like Caguas and San Juan who came fleeing political turmoil or to pursue business interests abroad.

Recent conversions

In recent years some Puerto Ricans have been reverting to the religion of their ancestors: Islam. How they wrestle with their identity as both Muslim and Puerto Rican is a key focus of my research.

Straddled between a predominately Arab Muslim population on the one hand and their avowedly Puerto Rican families, neighbors and coworkers who imagine Islam as something foreign to, rather than part of, Puerto Rico, converts struggle to marry the two identities they now claim. They are in search of a Boricua “Islamidad” – a unique Puerto Rican Muslim identity that resists complete assimilation to Arab cultural norms even as it reimagines and expands what it means to be Puerto Rican and a Muslim.

Puerto Rico Islamic Center at Ponce in Barrio Cuarto, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Roca Ruiz, CC BY-SA

In each of Puerto Rico’s nine mosques, researchers have found an increasing number of recent local converts. There is no accurate measure, but anecdotal evidence suggests rising numbers.

One of them is Juan, whom I first met at an Eid al-Fitr – the festival of breaking the Ramadan fast – celebration at the San Juan Convention Center in 2015. The 40-something man of Dominican descent and Puerto Rican heritage said,

“I came to Islam by asking questions: about the ills of society, the difficulties of life.”

Juan found that Catholicism, the religion adopted by his ancestors when they converted, was too confusing, the doctrine of “tawhid” in Islam – the oneness of God – simpler than what he believed to be the complex theology of the Trinity. Furthermore, he felt that Islam called for a higher morality and sense of self-discipline. And so, he “reverted” – that is, returned to the faith of his birth and the heritage of his Iberian forebears in al-Andalus, in what is modern-day Spain.

And so, he “reverted” – that is, returned to the faith of his birth and the heritage of his Iberian forebears in al-Andalus, in what is modern-day Spain.

But Juan, like many other converts, is also searching for a sense of authenticity in his new community. While Juan finds that his Muslim brothers and sisters appreciate him, he still feels marginalized because of his cultural background. He finds ways to express his “Boricua” (a term for resident Puerto Ricans, derived from the island’s indigenous name Borinquen) pride and his Muslim identity by sporting a “taqiyah” (a short, rounded skull cap) decorated with the Puerto Rican flag.

Another Puerto Rican convert from Aguadilla, Abu Livia, lives in this tension as well. He told me during an interview, “too often we hear people say you have to wear certain clothes, speak a certain language, look like an Arab, talk like an Arab, behave like an Arab.”

Not just Juan and Abu Livia, as I found in my research, but many other Puerto Rican Muslims are looking toward Andalusia, or Moorish Spain, to define who they are in a Puerto Rican society that claims a mixed background of indigenous, African and European influences.

Combining traditions

As such, Puerto Rican Muslims are finding ways of expressing their Muslim faith through symbols of Puerto Rican culture, whether it be their flag, their family traditions or their food.

Walking toward his home at the end of a long day of work, Juan looks forward to a quiet “iftar” – a meal to break the daily fast – with his family. It’s hot; beads of sweat have gathered like the faithful for prayer on his forehead; his legs are almost to the point of dragging up the small hill to his home; and the difficulties of Ramadan in a Caribbean climate weigh upon him. Even so, he smiles and gives praise to Allah.

As the sun sets and Juan prepares a light Puerto Rican meal of tostones – twice-fried plantains – his sincerity toward both his culture and his faith cannot be challenged.

“If anyone questions my religion,” said Juan, “they cannot question my ‘taqwa,’ my intention and fear of God.”

How Puerto Ricans are returning to Islam

How Puerto Ricans Return to Islam

For Juan, Ramadan is, in a sense, a search for balance. On the one hand, his faith and religious practice; on the other hand, its land, culture and home is Puerto Rico.

On the one hand, his faith and religious practice; on the other hand, its land, culture and home is Puerto Rico.

Although in many ways he combines these two elements of his identity, in Ramadan the border between them becomes tangible. For Puerto Rican Muslims like Juan, the holy month of Lent brings back to the surface the complexities they feel in their daily lives as a minority. nine0003

This year, it’s all felt even more strongly in light of the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which hit the southeastern city of Yabucoa on September 20, 2017 and devastated parts of Puerto Rico. Even now, many parts of the island are deprived of the basic benefits of civilization – electricity, water supply, access to schools.

Muslims first arrived on the island as part of a transatlantic colonial exchange between Spain and Portugal and the “New World”. There is evidence that the first Muslims arrived with seafarers as early as the 16th century. A large number of Iberian Muslims arrived in the Caribbean in violation of Spanish laws forbidding them to leave for America, some of them as a merchant or explorer, and some fell into slavery. nine0003

nine0003

Enslaved Muslims from West Africa began to arrive on the island from the 16th century. Their communities did not prosper and did not even really survive in Puerto Rico, but through them Islam entered the western hemisphere. Subsequently, due to conversion to Catholicism and the adoption of African American cults like Santeria, the influence of Islam in the region weakened, and the current Muslim population has little to no connection with the generations of Muslim slaves.

The current population of the island consists of recent immigrants from Arab countries. About two-thirds of Puerto Rican Muslims are Palestinians. nine0003

In recent years, Puerto Ricans have begun to embrace their ancestral religion, Islam. In each of the island’s 9 mosques, researchers are finding an increasing number of converts.

Newly converted Muslims here are trying to reconcile their 2 identities and are looking for the so-called. “boricua islamidad” is a unique Puerto Rican Muslim identity that opposes assimilation into Arab culture.

For Juan, the Catholicism adopted by his ancestors turned out to be too confusing doctrine. The concept of tawhid in Islam, the unity of God, seemed to him simpler than the complexity of understanding the Trinity. So he decided to return to the faith of his ancestors – that’s what he calls it. nine0003

After the devastating hurricane Maria, the month of Ramadan is especially important for Puerto Rican Muslims – it brings them a kind of revival, renewal.

Juan says Puerto Rico will rise above hardships this Ramadan through fasting, prayer and almsgiving.

Translation from English specially for Ansar. Ru

Source: The Conversation

10:27 June 06, 2018

nine0035

0 comments

Islam and Muslims in Switzerland

Information from Switzerland in 10 languages

close

Search

History

Islam has become the country’s third largest denomination. Should it be given the same status as the Christian churches, i.e. become a “national church” (Landeskirche)?

Should it be given the same status as the Christian churches, i.e. become a “national church” (Landeskirche)?

This content was published on March 12, 2020 – 11:51

nine0050

March 12, 2020 – 11:51 am

Corinna Staffe (Illustration)

Original Russian version: Igor Petrov.

In Switzerland, freedom of opinion, conscience and religion is protected by law, in particular by the Constitution. However, not all religious communities have equal legal status in the country.

According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (BfS), about 380,000 Muslims lived in Switzerland in 2017 (5.4% of the total population). Thus, Muslims are the third largest religious community in the country after the Roman Catholic denomination (35.9%) and the Protestant (Reformed) community (23.8%).

Show more

With the exception of the cantons of Geneva and Neuchâtel, Catholic and Protestant churches (Christian religious communities) are recognized under public law in all cantons. Jewish communities have the status of public institutions only in four cantons: Bern, Friborg, Basel and St. Gallen.

Jewish communities have the status of public institutions only in four cantons: Bern, Friborg, Basel and St. Gallen.

Show more

Recognition of Islam under public law as the “national church” would not only give it advantages, but would also impose certain and rather strict obligations on it. Islamic structures would be able to collect taxes from believers in their income, gaining endowed access to such public institutions as schools, hospitals and prisons. nine0003

Show more

On the other hand, the Islamic community would then become the object of state political oversight and financial audit. Now some mosques in Switzerland receive direct financial support from abroad, and the authorities are completely unaware of the extent of this support and what influence and how foreign donors and patrons of art have on the minds of Swiss Muslims.

Show more

nine0002 So maybe it is worth recognizing the Muslim religious community in accordance with public law and thus bringing more clarity to the nature of the functioning of this important social group? State recognition would help Muslim social structures and institutions in Switzerland to free themselves from foreign guardianship.

Show more

This opinion is shared by Mallory Schneuwly Purdie ( Mallory Schneuwly PurdieExternal link ), leading expert of the “Swiss Center for Society and Islam” ( Schweizerisches Zentrum für Islam und GesellschaftExternal link ) at the University of Friborg. Switzerland is not yet ready for this! This is the opinion of her colleague Andreas Tunger-Zanetti ( Andreas Tunger-ZanettiExternal link ) from the University of Lucerne.

Show more

In general, in Switzerland, church and state are strictly separated from each other, but in some areas (charity, counseling, the social sphere) they work closely together. One way or another, Switzerland has 26 cantons (sovereign subjects of the federation) and the rights of religious communities are regulated there differently each time. nine0003

Show more

At the same time, all cantons, one way or another, act on the basis of the same principle: if recognized from the point of view of public law, then not religion (Islam), but some one leading Muslim religious social structure. But then the question arises: which structure should be preferred and on the basis of what criteria?

But then the question arises: which structure should be preferred and on the basis of what criteria?

Show more

Muslims in Switzerland are a very heterogeneous social group, people who profess Islam live here, but at the same time they can have a variety of traditions, cultures and worldviews. In fact, the influential Federation of Islamic Public Organizations, Associations and Associations of Switzerland (Föderation islamischer Dachorganisationen Schweiz FIDSExternal link ) represents about two-thirds of the faith communities.

Show more

The FIDS Charter (edition of 2016) does not specify legal recognition as a goal, which is logical: such recognition always, if it happens, is at the cantonal (regional) level, which means that recognition should be sought by the very same local Muslim associations and associations, collectively, make up FIDS.

Show more

No Muslim organization in any canton has so far applied for recognition to the authorities.