Mundillo puerto rico: Museo del Mundillo | Discover Puerto Rico

Nellie Vera | National Endowment for the Arts

Bio

The soothing sound of the wooden bobbins meeting each other as they weave the mundillo lace have always been part of the life of Nellie Vera, known affectionately by everyone as Doña Nellie. Born in the town of Moca, known as the “Capital of Mundillo” in Puerto Rico, she learned this traditional art form from her mother, Manuela Sánchez, when she was seven years old. Mundillo is a handmade bobbin lace made in a lap box called a telar. It holds a rounded pillow with a pattern secured by pins that guide the process of maneuvering the threads holding the wooden bobbins. The lace is produced by the weaving of the wooden bobbins, which in turn make a harmonious click-clack melody.

That sound is what made Vera fall in love with mundillo as a child when she visited with her mother and other weavers in town. This was in the Puerto Rico of the 1930s, when mundillo was a strong labor force in Moca. Industrialization brought many foreign and cheaply made laces, which led to the decline of the mundillo art form. Along this time, she earned her bachelor’s degree in education from the University of Puerto Rico and worked as a teacher. After retiring in 1980, she reunited with mundillo.

Along this time, she earned her bachelor’s degree in education from the University of Puerto Rico and worked as a teacher. After retiring in 1980, she reunited with mundillo.

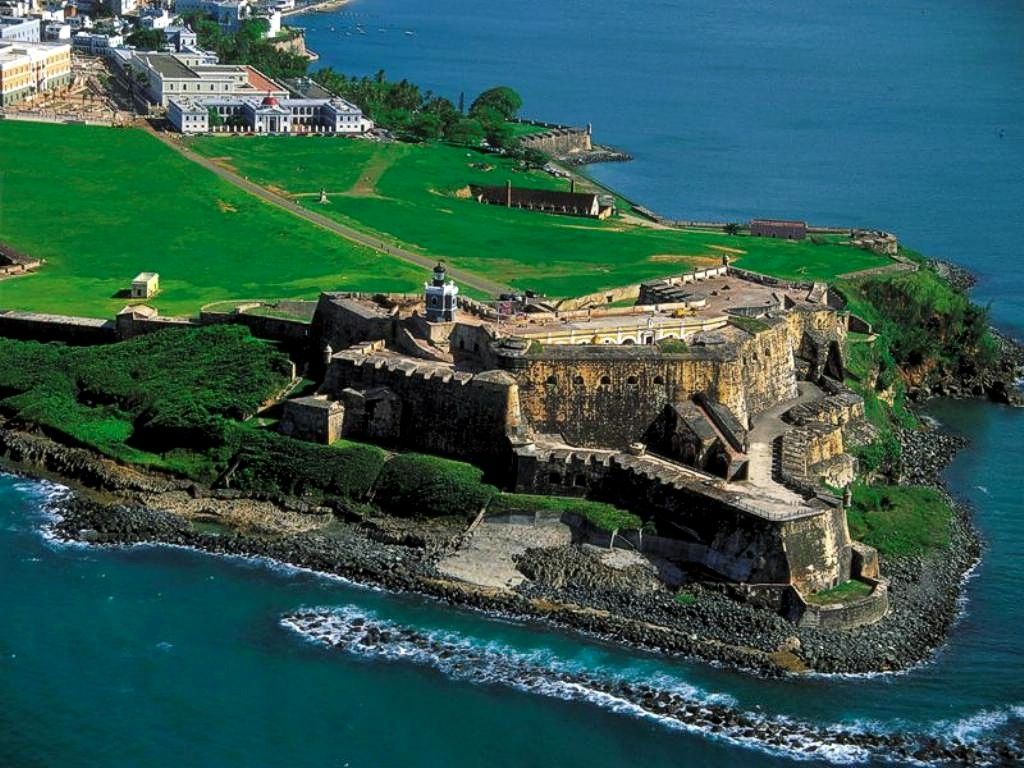

In 1982, she was one of the founding members of the Borinquen Lacers, a respected mundillo weavers collective affiliated with the International Old Lacers. She also presided for 20 years in the Taller de Artesanos Mocanos, a nonprofit that fostered the work of more than 300 artisans from the town of Moca, and, alongside other mundillo weavers, pushed for the creation of the Museo del Mundillo. On an island where most of the cultural institutions are established in the capital of San Juan, Vera was adamant that if a mundillo museum was going to be created, it had to be in Moca, where it is now established.

In 2000, her work received an honorific mention in the first edition of FERINART, the International Arts & Crafts Fair in Puerto Rico. Then in 2004, she was awarded a national recognition as a Master Artisan by the Puerto Rican Artisanal Development Program under what is now the Department of Economic Development and Commerce. In 2009, she received the Artisanal Excellence Award from the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. In 2012, Vera was recognized as an Outstanding Artisan by the Puerto Rican Artisanal Development Program and in 2014, as National Symbol. Then in 2015, she was inducted into the Artisan Hall of Fame of Puerto Rico. She has also been lecturer in the Incarnate Word College of Texas (1995) and in The Field Museum de Chicago (2006).

In 2009, she received the Artisanal Excellence Award from the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. In 2012, Vera was recognized as an Outstanding Artisan by the Puerto Rican Artisanal Development Program and in 2014, as National Symbol. Then in 2015, she was inducted into the Artisan Hall of Fame of Puerto Rico. She has also been lecturer in the Incarnate Word College of Texas (1995) and in The Field Museum de Chicago (2006).

After dedicating more than 40 years to the art of mundillo, Vera not only still finds the essence of nature in its intricate designs, but also describes it as her way of life.

By Jessabet Vivas-Capó, Program Advisor and Interim Director of the Folk Arts and Creative Industries Program, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña

Related Video

Stay Connected to the National Endowment for the Arts

Sign up for our newsletters and magazine

Newsletter Signup

Magazine Signup

Mundillo nuestro: by Antonio Martorell and his friends

“Mundillo nuestro” (Our Little World in Bobbin Lace), the stage curtain commissioned by the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico to Antonio Martorell for its Raúl Juliá-Banco Popular Theater, is a monumental piece that far exceeds the traditional dimensions of lacemaking. The inspiration for the piece emerged from several projects and exhibitions that Antonio Martorell had worked on, ideas that wove together to produce this tour de force of collective labor under his direction.

The inspiration for the piece emerged from several projects and exhibitions that Antonio Martorell had worked on, ideas that wove together to produce this tour de force of collective labor under his direction.

Early on in his artistic career, Martorell began to incorporate pieces of lace, embroidery, and textures alluding to the manual work of seamstresses and weavers into his work as formal and thematic details. His childhood years among fabrics, ribbons, and embroidered pieces in his mother’s shop, the Las Muchachas Bazaar, and at the feet of the Singer sewing machine in his house impressed on his memory those elements of beauty and sensuality. The finishes on a dress, a runner, or a tablecloth, the cuffs or collar of a blouse, delicate handkerchiefs, and mantillas are referents Martorell always returns to in his art.

Mundillo lace is made in stages from precise patterns that guide the hands in the crisscross of threads that make up the web—a veil or latticework that extends outward to the limits of the pattern that serves as support in that back- and-forth, over-and-under weaving of the threads. The weaving process, which dates back thousands of years and is performed singly or in groups, as a craft or industrially, with all its technical and formal variants, is a fundamental element in almost all the world’s cultures.

The weaving process, which dates back thousands of years and is performed singly or in groups, as a craft or industrially, with all its technical and formal variants, is a fundamental element in almost all the world’s cultures.

The exhibition “Mundillo nuestro: by Antonio Martorell and his friends” exhibits several common threads (as it were) that can be traced throughout his life and artistic career. Exposed to films, plays, and musical theater from a young age, Martorell soon began recognizing the natural links between stage, museum, life, and daily experiences. In the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP) Graphics Workshop with Lorenzo Homar, he worked in support of the ICPR’s theater festivals and for independent productions by such companies as the Taller de Histriones. He created posters and stage settings, designed costumes and even makeup for dancers in the performance of Las Loas. His immersion in the contemporary arts of Mexico City in the early eighties led him to explore the art of installations. And beginning in 1984, with his return to Puerto Rico, he took part in collective workshops and graphic-theater pieces with Rosa Luisa Márquez. From those experiences in experimental theater, he transitioned onto the stage as an actor and, on other occasions, as a performance artist.

And beginning in 1984, with his return to Puerto Rico, he took part in collective workshops and graphic-theater pieces with Rosa Luisa Márquez. From those experiences in experimental theater, he transitioned onto the stage as an actor and, on other occasions, as a performance artist.

His bond with the theater that arose out of Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed and the Bread and Puppet Theater of Peter Schumman (to which he was led by Rosa Luisa Márquez and the Teatreros Ambulantes de Cayey) enriched his stage-design work for the opera and his monumental portraits of the principal exponents of Puerto Rican bel canto. The MAPR’s commission for a stage curtain for the Raúl Juliá-Banco Popular Theater came in recognition of Martorell’s work at the intersection of the plastic and theater arts. He had already presented the series Mundillos Desencajados (“Worlds Shaken, Dislocated, and Distressed”), world maps woven in large format, at international exhibitions in Copenhagen and the Whitney Biennial in New York. The idea of a bobbin-lace curtain originated with two key figures in the history of the MAPR’s foundational project: architect Otto Reyes and the director of the museum project at its inception, Adlín Ríos Rigau. The Borinquen Lacers, a weavers collective, had already worked with Martorell to make the large-scale “mapas desencajados.”

The idea of a bobbin-lace curtain originated with two key figures in the history of the MAPR’s foundational project: architect Otto Reyes and the director of the museum project at its inception, Adlín Ríos Rigau. The Borinquen Lacers, a weavers collective, had already worked with Martorell to make the large-scale “mapas desencajados.”

The shift in size of the map was a challenge that some of the weavers looked on a bit doubtfully, and with good reason, since the design was a great departure from the traditional idiom and scale of bobbin lace. The modification of the geographical layout was also a concern; one of the weavers, a geography teacher, was taken aback with the various maps studies that Martorell created. During those years, many changes were occurring in the planet’s geopolitics. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the war in the Balkans, the disappearance of the Soviet Union, tensions in the Caribbean, and anticolonial struggles in the Third World kept constantly reconfiguring the map. The composition of Martorell’s drawings and designs responded in the last resort to the political leanings and ideas he had held since his studies in diplomacy in Washington, D.C.

The composition of Martorell’s drawings and designs responded in the last resort to the political leanings and ideas he had held since his studies in diplomacy in Washington, D.C.

Over the years, in collaborative work and in the design of silkscreen posters, Martorell became adept at calligraphy and typography. His visits to the treasures of the Casa del Libro with the great graphic artists Lorenzo Homar, Rafael Tufiño, José Rosa, and Rafa Rivera broadened and deepened his graphic education. With this immersion, he began to create print portfolios dedicated to key figures in literature, politics, popular culture, philosophy, and poetry. And in those works we begin to see his strong preference for calligraphy, which takes on greater and greater prominence in the compositions. Indeed, with calligraphy Martorell began to do “lettered portraits,” as he called them. The arabesques and filigrees that suggest the details of the faces expand into virtually the entire plane of the image. In these works we also see a loving web of twining leaves and vines weaving laces made of words. Geography and literature, poetry and politics entwine and disentwine in the universe of the artist and his friends.

Geography and literature, poetry and politics entwine and disentwine in the universe of the artist and his friends.

“Mundillo nuestro” speaks to us of our cultural complexity in this time of challenges stemming from global transformations and the enormous political, racial, social, financial, and religious tensions we live in. Massive migrations, border conflicts, and threatened sovereignties show both the fragility and resilience of our cultural fabrics. This interwoven lace supports the knowledge deposited in it for centuries for resisting both natural and imposed erosion. The paths of the threads, their crossings and ties, born of the lacemaker’s art, sustain us all in these days of retrogression, resistance, and struggle.

-Humberto Figueroa, Guest curator

*This exhibition is sponsored by the Special Joint Committee on Legislative Donations for Community Impact.

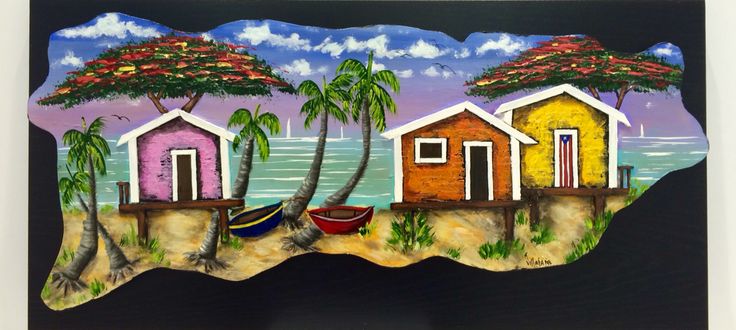

Moca, Puerto Rico

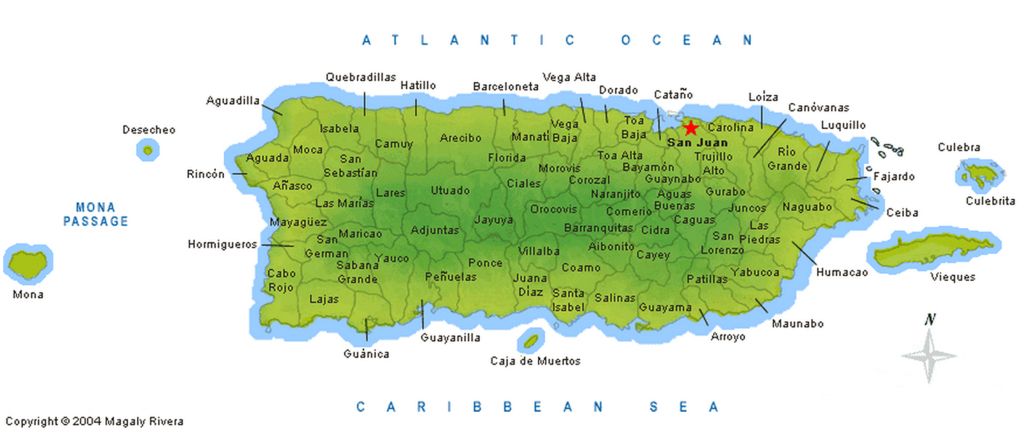

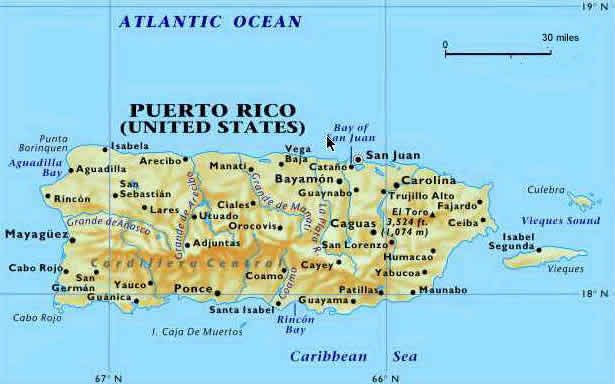

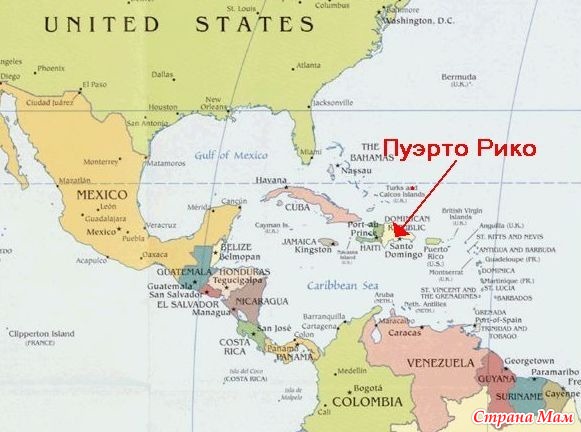

Moca ( Spanish pronunciation: [Omoca]) is a Puerto Rican municipality located in the northwestern region of the island, north of Añasco; southeast of Aguadilla; East Aguada; and west of Isabela and San Sebastian. Moca is spread over 12 barrios and Moca Pueblo (business district and administrative center of the village). It is part of the Aguadilla-Isabela-San Sebastian Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Moca is spread over 12 barrios and Moca Pueblo (business district and administrative center of the village). It is part of the Aguadilla-Isabela-San Sebastian Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The name Moka comes from a tree Andira inermis whose beautiful pink/purple flowers reveal their presence, which is very common in this region.

On February 19, 1972, the Moka tree was officially recognized as the city’s typical tree. Moka is famous for its Mundillo lace. Mundillo is the Puerto Rican name for handmade. bobbin lace. It is almost synonymous with the small town of Moka.

Contents

- 1 History

- 1.1 Hurricane Maria

- Agriculture: Fruit, dairy farming, cattle breeding. nine0019 Hacienda Labadie

- Palacete Los Moreau

- Coliseum Juan Sánchez Acevedo

Isla de Puerto Rico. “Estudio histórico, geográfico y estadístico” , published in San Juan in 1878 tells us that it was founded in 1774. On the other hand, Cayetano Coll y Toste, in “ Boletín histórico de Puerto Rico “, states that it was founded on June 22, 1772.

On August 14, 1898, the armed forces of the United States entered the city of Moka and took it unopposed. On August 8, 1898, after the Spanish–American War officially ended, Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States as a result of the Treaty of Paris 1898

On August 8, 1898, after the Spanish–American War officially ended, Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States as a result of the Treaty of Paris 1898

Hurricane Maria

Hurricane Maria On September 20, 2017, numerous landslides occurred in Moka with significant rainfall. [1] [2] About 1,300 houses were hit by landslides and floods, bridges collapsed, leaving residents without access to electricity, telecommunications services and basic necessities. After about a month and a half, 25% of Mok’s 31,117 residents received electricity and access to drinking water, while 75% did not. [3]

Geography

Labadie mansion inspired by Enrique Laguerre to write La Llamarada. The hotel has been restored as a museum and renamed Palacete Los Moreau, after the fictional characters of Laguerre.

Moca Pueblo, August 2006

Moca is located in the northwest. [4]

Location: 18°23’N and 67°06’W of the Greenwich meridian. It is located in a small valley at the foot of the Tuna Mountains, 141 feet (43 m) above sea level. nine0007

It is located in a small valley at the foot of the Tuna Mountains, 141 feet (43 m) above sea level. nine0007

Climate: Tropical with little seasonal variation. Temperatures throughout the year range from 24 to 37 °C (76–98 °F) and 10 to 24 °C (50 to 75 °F).

Hydrography: In the Rio Culebrinas crosses its territory from east to west, and its tributaries include the gorges of Los Gatos, Lassalle, de las Damas, Vieja, Los Romanes, Morones, Iguillo, Chiquita, Yagruma, Echeverria, Aguas Frias, Las Marias, de los Mendez, La Karaima, Grande, and Dulce, Cerro Moca, Monte El Ojo, Monte Mariquita of the Haikoa 9 mountain range0007

On May 16, 2010, Moka became the epicenter of a strong 5.8 magnitude earthquake. The quake was felt throughout the island, as well as in the Dominican Republic and the Virgin Islands. Damage was reported in various cities.

Barrios

Like all municipalities in Puerto Rico, Moca is subdivided into Barrios. The municipal buildings, the central square and the large Catholic church are located in the barrio called “El pueblo” . [5] [6] sectarians ( sector in English). Types cultists may differ from the usual sector to urbanization to reparto to barriada to residential , among others. [11] [12] [13]

[5] [6] sectarians ( sector in English). Types cultists may differ from the usual sector to urbanization to reparto to barriada to residential , among others. [11] [12] [13]

Special Communities

– These are marginalized communities whose citizens experience a certain social exclusion. The map shows that these communities are found in almost every Commonwealth municipality. Of the 742 places that were listed in 2014, the following neighborhoods, communities, sectors or neighborhoods were in Moca: Aceituna, Sector Isleta in Cruz Barrio, Parcelas Acevedo and Parcelas Mamey in Moca Barrio Pueblo and Loperena. ninePop.

9%

9%0236

1899 (shown as 1900) [16] 1910-1930 [17]

1930-1950 [18] 1960-2000 [19] 2010 [7]

The 2017 U. S. Census Bureau estimated that Moka had a total population of 36,328 residents (a significant decrease since 2010). [20] Like most Puerto Ricans, the Mocanos are a mixture of three races: Africans, Tainos and Europeans.

S. Census Bureau estimated that Moka had a total population of 36,328 residents (a significant decrease since 2010). [20] Like most Puerto Ricans, the Mocanos are a mixture of three races: Africans, Tainos and Europeans.

Economics

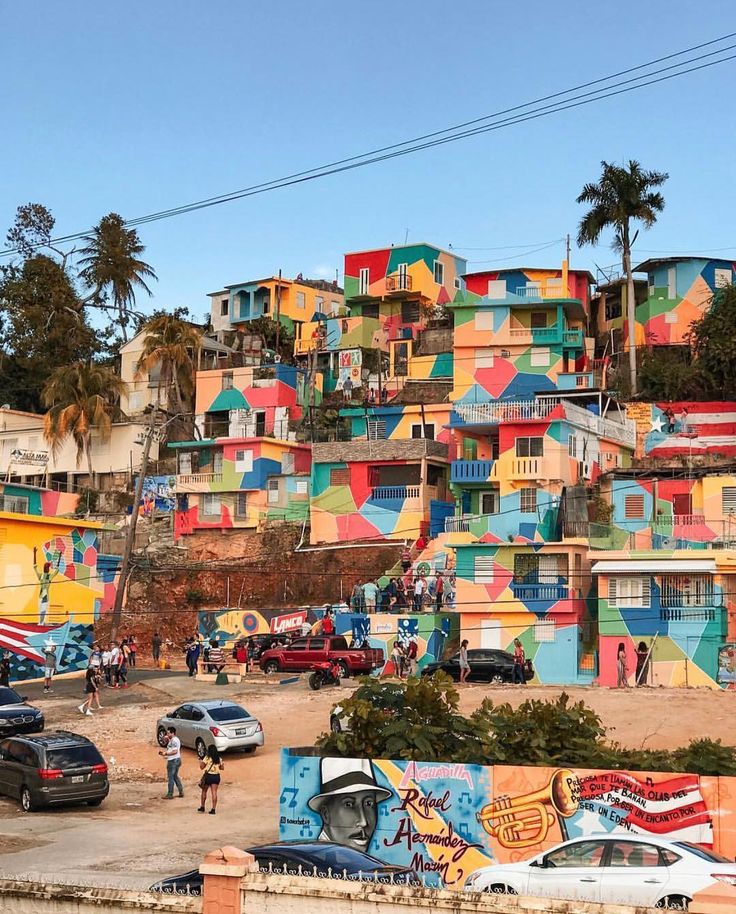

Culture

Festivals and Events

Moca celebrates its patron festival in late August / early September. At Fiestas Patronales Nuestra Señora de la Monserrate is a religious and cultural celebration that usually includes parades, games, artisans, rides, regional food and live entertainment. [4] [21]

Sports

Moca has a Double-A (baseball) team named the Moca Vampiros who play in Major League Baseball. nine0007

Moca also had a volleyball team called “Los Rebeldes” that played in the LVS (Liga de Voleibol Superior) through the years 1998 to 2005 the team went to the post season every year, obtained a controversial second place in his 1998 final “Chango” Naranjito. In addition, Los Rebeldes became national champions against Chango in the 2000 final. Los Rebeldes edged out Changos 4–0 in the final.

In addition, Los Rebeldes became national champions against Chango in the 2000 final. Los Rebeldes edged out Changos 4–0 in the final.

Vampire myth

Moca is famous in Puerto Rico for El Vampiro de Moca. El vampiro de Moca was believed to exist because cows were found dead after having tusk holes in their necks. With this phenomenon, not only cows appeared, but also sheep and goats.

Government

Main article: Puerto Rico City Hall

Like all municipalities in Puerto Rico, Moca is administered by a mayor. The current mayor is José Aviles Santiago, from the New Progressive Party (PNP). Aviles was elected in the 2000 General Election.

The city belongs to Puerto Rico Senatorial District IV, which is represented by two senators. In 2012, Maria Teresa Gonzalez and Gilberto Rodriguez were elected district senators. [22]

Transport

There are 12 bridges in Moka. [23] Moka used to have a taxi system or “Carros Públicos”, but these were eliminated due to the popularity of the car.

Symbols

Flag

Eric De Jesus was the designer of the flag. The rectangular flag consists of a magenta equilateral triangular field, the color of the flower of the Moka tree. In this field appear five-pointed stars, silvered, surrounding a large golden star, also with five points. nine0095 [24]

Coat of arms

It has an oblong shape. Separated by a silvered field and a blue sky connected by a magenta rhombus (diamond shape) the color of the Moka flower. The rhombus has religious symbolism. The rhombus is flanked at its bottom by two branches of the Moka tree; in the upper part – an arc of eleven five-pointed stars covered with silver. Inside the rhombus is a golden monogram (of the Virgin Mary) surmounted by a Christian crown of the same metal. The shield is crowned with a silver-plated crown in the form of a three-towered castle. On the front of the crown, carved in gold, is the word Moca. The castle stones are laid out in blue. The doors and windows are purple. nine a b “MOCA”. LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

nine a b “MOCA”. LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

Share

Pin

Tweet

Send

Share

Send

Mundillo (Shilteri lace)

Mandillo Bul Zhalman Zolөner Shillenda өsirilgen zhәne q nortoro puerto puero Pena Pena. [1] ‘Mundillo’ terminі shіlter zhasaushy (‘Mundillista’) kүrdelі oulardy toқityn tsilindlіk zhastyққa katysty ‘kіshkentai alem’ degendi bіldіredі. Sandik shilter agashtan zhasalgan bobinder burandastyrylgan zhippen oralgan karyndashtyn diameter turaly ornek. Ylgige baylanysty ekі-onnan az nemese bіrneshe zhүzdegen bobinalar қoldanyluy mүmkin. nine0095 [ dәyeksoz kazhet ] Adette Mundilyonyң astanasy nemese besіgі retіnde belgіlі Mokada [4] kolmen toқylғan shіlterge arnalғақай festival, sonday-аұақай [5]

Mundillo merekelenedi zhane araldyn ainalasyndagy festivaldard korsetіledi.