Puerto rico encyclopedia: Puerto Rico | Encyclopedia.com

Puerto Rico Encyclopedia/Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Encyclopedia

http://www.enciclopediapr.org/

Created and maintained by the Puerto Rican Humanities Foundation.

Reviewed June, 2012.

In 2008, the Puerto Rico Encyclopedia Web site was launched to the public as a bilingual (English and Spanish) educational project of the Puerto Rican Humanities Foundation (fph). Using public and private funding, the fph, a nonprofit institution affiliated with the National Endowment for the Humanities, collaborated with six higher education institutions in Puerto Rico and two in the United States. The site’s team of editors consists of recognized scholars and intellectuals in Puerto Rico. Their goal is to present a wide range of Puerto Ricorelated information, grounded in a humanistic approach and using innovative technology. The main focus is to serve as an information tool for K12 students, people of Puerto Rican descent, and the general public interested in Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in the United States.

Miguel Henrquez, Puerto Rican privateer

The Puerto Rico Encyclopedia presents a variety of perspectives on history, society, and culture. It consists of sixteen sections that combine essays, documents, photos, and videos on subjects ranging from pre-Columbian populations to Puerto Ricans in Florida. Most of the sections highlight cultural and artistic themes through essays on architecture, music, visual and performing arts, literature, and folklore. In the history section, the emphasis on pre-twentieth-century history reproduces a view of history as something from the past disconnected from the present. At the same time, the essays on twentieth-century history are limited to the topics of agrarian reform, the mid-twentieth-century industrialization project Operation Bootstrap, and the 1937 Ponce Massacre. The site could have taken advantage of the vast literature on this period, which is important to understanding contemporary Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans. The sections on gender relations, emigration, and immigration present new and innovative ways to interpret the Puerto Rican experience. In addition, better bibliographic sources should also be added to some essays, such as the section on fertility, which ignores most of the feminist and political economy literature on the subject.

The sections on gender relations, emigration, and immigration present new and innovative ways to interpret the Puerto Rican experience. In addition, better bibliographic sources should also be added to some essays, such as the section on fertility, which ignores most of the feminist and political economy literature on the subject.

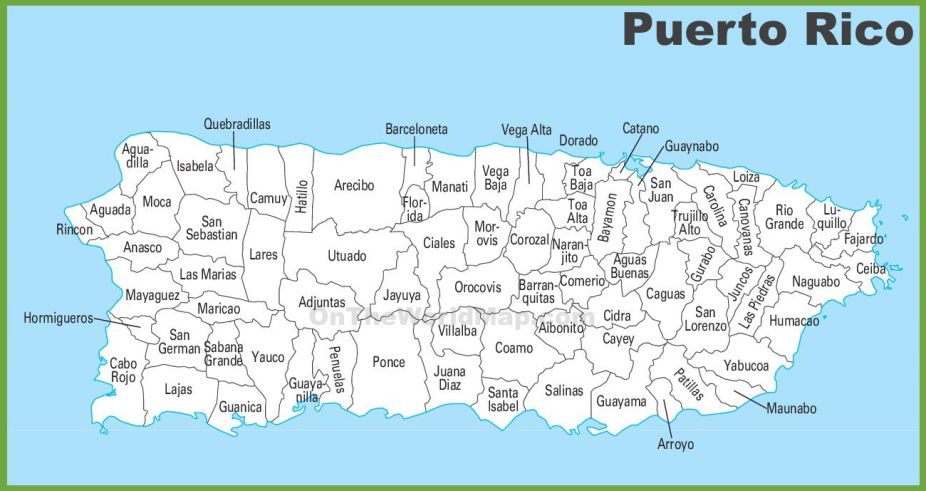

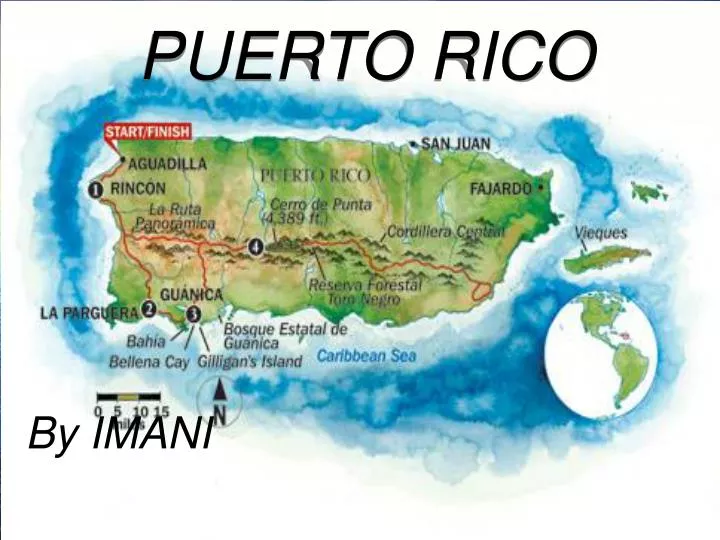

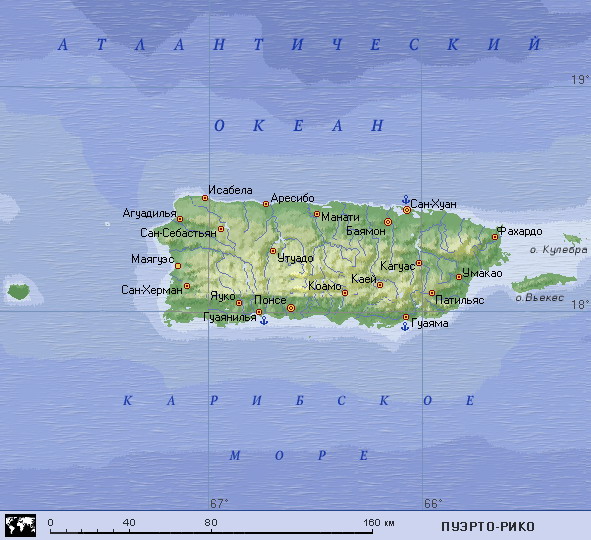

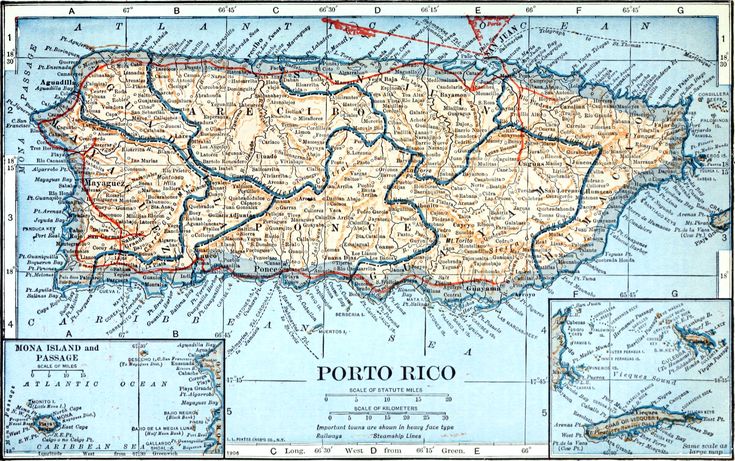

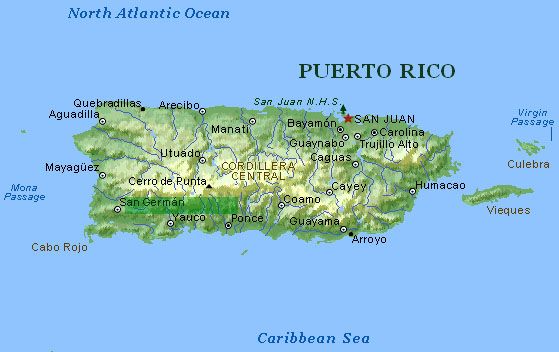

The presentation of quotes, facts, and trivia is very impressive as are the site design and the photos. The site also has easily navigable galleries with videos, photos, and a map of Puerto Rico containing basic information on each municipality and cultural routes through the islands. Unfortunately, this project is still a work in progress. Some of the subsections lack essays and other sections are very limited in scope. A section on the Caribbean region deviates from the main goal of the site. Finally, the Puerto Rico Encyclopedia needs a better way to reach out to the public. As a scholar in the field of Puerto Rican studies, I never heard about this site before being presented with the opportunity to review it. One of the reasons behind its lack of public outreach could be the limited network of scholars involved in the project. Nevertheless, Puerto Rico Encyclopedia represents an important resource for wider public access to scholarly knowledge about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans.

One of the reasons behind its lack of public outreach could be the limited network of scholars involved in the project. Nevertheless, Puerto Rico Encyclopedia represents an important resource for wider public access to scholarly knowledge about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans.

Ismael García-Colón

College of Staten Island

City University of New York

Staten Island, New York

Brief history of Puerto Rico

In the photo, women working in the needle industry, 1950s.

Puerto Rico is the smallest of the Greater Antilles and the largest of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. It was a Spanish colony for four centuries and has been a colony of the United States since 1898.

Symbol of the goddess of fertility Atabeira and Atabex

The first inhabitants, called the Archaics, came from the Orinoco River delta in the north of South America thousands of years ago. Archaeologists have documented a human presence on this land since 4,000 (at Angostura, Barceloneta) and 3,000 B. C. (at Maruca in Ponce). When the Spanish came to Boriquén (the name the native inhabitants gave the Island) in Christopher Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, they affected the Tainos, the descendants of the Arawak people from northern Venezuela. The Tainos were the product of a fusion of various earlier cultures. They had developed productive agriculture and applied knowledge of astronomy and meteorology. They believed in multiple gods. Their society was ruled in a pyramidal structure led by a cacique to whom they paid tribute. It was an intermediate social, economic and political structure whose subsequent stage was represented in the Americas by the city-states exemplified by the Aztecs, Mayans and Incas. The Taino indigenous heritage has left a significant mark on Puerto Rican culture.

C. (at Maruca in Ponce). When the Spanish came to Boriquén (the name the native inhabitants gave the Island) in Christopher Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, they affected the Tainos, the descendants of the Arawak people from northern Venezuela. The Tainos were the product of a fusion of various earlier cultures. They had developed productive agriculture and applied knowledge of astronomy and meteorology. They believed in multiple gods. Their society was ruled in a pyramidal structure led by a cacique to whom they paid tribute. It was an intermediate social, economic and political structure whose subsequent stage was represented in the Americas by the city-states exemplified by the Aztecs, Mayans and Incas. The Taino indigenous heritage has left a significant mark on Puerto Rican culture.

The Spanish colony

Columbus named Boriquén San Juan Bautista when he stopped at the Island on November 19, 1493, but it was not until 1508 that the Spanish established a permanent presence with Juan Ponce de León as the first governor. The subjugation and mistreatment of the indigenous people caused a rebellion in 1511, but there was little their stone hatchets could do against the arquebuses and other weapons and strategies of the conquistadors. Additionally, the imported diseases and harsh conditions of the forced labor reduced the indigenous population. Their role as forced labor was replaced by slaves from western Africa. The crossing of these three ethnicities (Taino, Spanish and African) represents the ethnic and cultural origin of the Puerto Ricans. The racial and cultural mixing continued in the following centuries with the arrival of other immigrants, such as free blacks from neighboring islands (in the 18th century), white Europeans (in the 18th century) and, later, people from the United States, Cuba and the Dominican Republic (in the 20th century).

The subjugation and mistreatment of the indigenous people caused a rebellion in 1511, but there was little their stone hatchets could do against the arquebuses and other weapons and strategies of the conquistadors. Additionally, the imported diseases and harsh conditions of the forced labor reduced the indigenous population. Their role as forced labor was replaced by slaves from western Africa. The crossing of these three ethnicities (Taino, Spanish and African) represents the ethnic and cultural origin of the Puerto Ricans. The racial and cultural mixing continued in the following centuries with the arrival of other immigrants, such as free blacks from neighboring islands (in the 18th century), white Europeans (in the 18th century) and, later, people from the United States, Cuba and the Dominican Republic (in the 20th century).

Cemí taíno

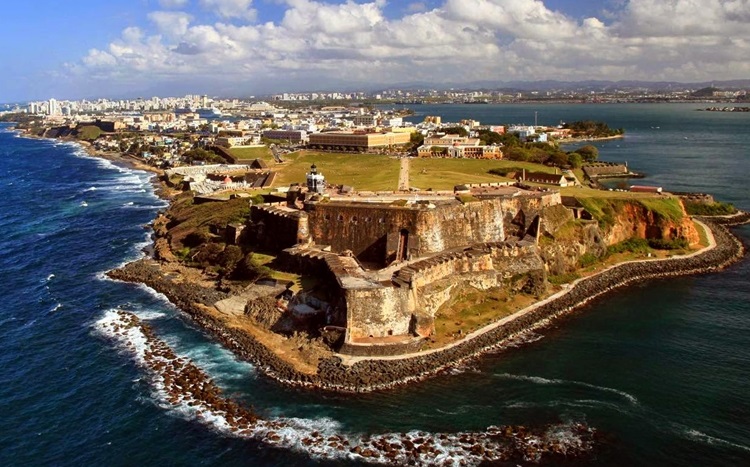

The colony grew rapidly and was one of the bases of support for the Spanish imperial advance into the continents. The main city was called Puerto Rico, for its spacious bay and natural port. In 1522, San Juan de Puerto Rico was founded as its capital, after moving from Caparra, the initial enclave of the management of the conquest and colonization. By 1582, the total Island was identified as Puerto Rico. While the empire grew and faced the rivalries of other European powers, the Island’s strategic and military importance overshadowed its economic value (especially after the conquest of the wealthy civilizations of the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas in Peru). For a growing empire, Puerto Rico became “the key to the Indies,” a crucial site for repelling intruders and those who were not loyal to the Spanish Main.

In 1522, San Juan de Puerto Rico was founded as its capital, after moving from Caparra, the initial enclave of the management of the conquest and colonization. By 1582, the total Island was identified as Puerto Rico. While the empire grew and faced the rivalries of other European powers, the Island’s strategic and military importance overshadowed its economic value (especially after the conquest of the wealthy civilizations of the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas in Peru). For a growing empire, Puerto Rico became “the key to the Indies,” a crucial site for repelling intruders and those who were not loyal to the Spanish Main.

The rise of Puerto Rican sentiment

Governor Miguel Antonio de Ustáriz (1789-1792), painting by José Campeche. Collection of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture.

EPride in being Puerto Rican, not Spanish, arose among the Island residents at least as early as the 18th century. This is evident in the paintings by José Campeche (1751-1809), the first important Puerto Rican painter of the time, who was the son of a freed slave and a white woman from the Canary Islands. His paintings (some of which were wrongly attributed to Francisco de Goya in Spain) were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1988. From Campeche on, expressions of Puerto Rican identity have been a constant in our visual arts. This sense of our differences from the Spanish were reaffirmed after the victory against the invading British in 1797. It also led the Island residents to demand political, social and economic reforms in the early 19th century. The feeling of Puerto Ricanness that developed over the years found its first political expression in the election of Ramón Power, the first representative of Puerto Rico in the Cortes of Cádiz. Juan Alejo de Arizmendi, the first and only Puerto Rican bishop under Spanish rule, named in 1803, also reinforced the prominence of Puerto Rican heritage when, in 1809, he charged Power with protecting “the rights of our countrymen.”

His paintings (some of which were wrongly attributed to Francisco de Goya in Spain) were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1988. From Campeche on, expressions of Puerto Rican identity have been a constant in our visual arts. This sense of our differences from the Spanish were reaffirmed after the victory against the invading British in 1797. It also led the Island residents to demand political, social and economic reforms in the early 19th century. The feeling of Puerto Ricanness that developed over the years found its first political expression in the election of Ramón Power, the first representative of Puerto Rico in the Cortes of Cádiz. Juan Alejo de Arizmendi, the first and only Puerto Rican bishop under Spanish rule, named in 1803, also reinforced the prominence of Puerto Rican heritage when, in 1809, he charged Power with protecting “the rights of our countrymen.”

The 19th century was very chaotic in Spain and brought significant changes to Puerto Rico. It began with the invasion by Napoleon of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808, a situation that in part encouraged the wars of independence and the loss of all the Spanish possessions on the American continents. Therefore, open expressions of Puerto Rican identity were considered subversive by a government that tried to keep the Island free of the revolutionary “contagion,” especially from nearby Caracas, which was considered a center of anti-Spain separatists. By the middle of the 1820s, only Cuba and Puerto Rico, in the Caribbean, remained under Spanish rule as a result of the establishment of repressive governments on those islands, with the complicity of the dominant slave-owning classes. The immigration of hundreds of monarchists who escaped Venezuela strengthened the conservative and pro-Spanish political sector on both islands.

It began with the invasion by Napoleon of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808, a situation that in part encouraged the wars of independence and the loss of all the Spanish possessions on the American continents. Therefore, open expressions of Puerto Rican identity were considered subversive by a government that tried to keep the Island free of the revolutionary “contagion,” especially from nearby Caracas, which was considered a center of anti-Spain separatists. By the middle of the 1820s, only Cuba and Puerto Rico, in the Caribbean, remained under Spanish rule as a result of the establishment of repressive governments on those islands, with the complicity of the dominant slave-owning classes. The immigration of hundreds of monarchists who escaped Venezuela strengthened the conservative and pro-Spanish political sector on both islands.

Social and economic changes in the 19th century

Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

Announcement of the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

After the defeat of the Napoleonic forces in 1814, Fernando VII returned to Spain and decided to keep Puerto Rico loyal and secure through economic reforms. Additionally, because of the Haitian revolution, fear of slave rebellions on one hand led to greater repression of the forced laborers along with the arrival of more Europeans. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 encouraged immigration of white Catholics. As a result, the demographics of Puerto Rico changed, as hundreds of French (mostly white islanders from Haiti, Louisiana, Guadalupe and Martinique), Italians and Irish arrived on the Island with their slaves. Many African slaves were also smuggled in. In the middle of the century, a new wave of immigrants arrived from Corsica, Mallorca and Catalonia.

Additionally, because of the Haitian revolution, fear of slave rebellions on one hand led to greater repression of the forced laborers along with the arrival of more Europeans. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 encouraged immigration of white Catholics. As a result, the demographics of Puerto Rico changed, as hundreds of French (mostly white islanders from Haiti, Louisiana, Guadalupe and Martinique), Italians and Irish arrived on the Island with their slaves. Many African slaves were also smuggled in. In the middle of the century, a new wave of immigrants arrived from Corsica, Mallorca and Catalonia.

The royal decree, along with others, led to economic and social changes. There was a notable increase in agricultural production of three commercial crops: sugar cane, coffee (introduced in the middle of the 18th century and quickly becoming an import export to Europe) and tobacco. The plantation system was widely adopted and with the increase in sugar production came a growth in African slave trade, as in the rest of the Caribbean.

The plantation system was widely adopted and with the increase in sugar production came a growth in African slave trade, as in the rest of the Caribbean.

Eventually, the growing demand for labor and the difficulty in acquiring slaves, given the restrictions on the slave trade, led the landowners to look to the free population of the Island, which was bigger than the slave population. The landowners convinced the government to establish a mechanism to force the peasants who did not own land, the majority of the population, to work as day laborers. They also had to carry a booklet in which their employers noted the dates they worked. This system lasted from 1849 to 1873.

By this time, a local island elite, mostly urban, had developed and demanded a role in the affairs of the Island, demands that the Spanish government resisted and persecuted. Some youths who had the resources or could get scholarships went to Europe to study after graduating from the Council Seminary in San Juan. A generation of Puerto Rican students in Spain, in the 1840s and 1850s, produced foundational texts of our literature and the emblematic figure of the jíbaro, the white rural peasant of the mountains.

A generation of Puerto Rican students in Spain, in the 1840s and 1850s, produced foundational texts of our literature and the emblematic figure of the jíbaro, the white rural peasant of the mountains.

The abolition of slavery and the call for independence from Spain arose as counter discourses mainly among local island liberals. The most extreme were exiled and, even in exile, the leader of the pro-independence movement, Ramón Emeterio Betances (a doctor educated in France) promoted the most forceful revolutionary attempt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico, the Grito de Lares in 1868. The revolt was put down in short order, although it had both short and long-term consequences. For example, the following year, Spain allowed the formation of a first political party, which was followed a few months later by another. On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished and on July 13 of the same year the labor booklet system was eliminated.

This same generation of Puerto Ricans outlined a liberal project beginning in the middle of the 19th century, in part because the sugar crisis revealed the vulnerability of the Island economy. The new intellectual elite, mostly living in Ponce and San Juan, wanted economic, social and cultural progress. They created cultural institutions such as the Puerto Rican Athenaeum in 1876. Newspapers appeared everywhere, giving voice to the demands for change. The locals were up to date on progressive ideas (including democracy in the United States, which was already the second most important country in terms of trade with Puerto Rico) and events in other parts of the world that influenced them.

The new intellectual elite, mostly living in Ponce and San Juan, wanted economic, social and cultural progress. They created cultural institutions such as the Puerto Rican Athenaeum in 1876. Newspapers appeared everywhere, giving voice to the demands for change. The locals were up to date on progressive ideas (including democracy in the United States, which was already the second most important country in terms of trade with Puerto Rico) and events in other parts of the world that influenced them.

The Canadian model of autonomous government inspired a new project among the intellectuals of the southern city of Ponce, led by Román Baldorioty de Castro, that resulted in the founding of the Autonomist Party in La Perla Theater in 1887. The same year, one of the most radical movements in our history arose, the Boycott movement, influenced by the Irish Land League. This secret society committed to boycotting Spanish businesses and promoting only Puerto Rican businesses. The Spanish government responded with persecution and torture of the autonomists in measures known as the Compontes. The main leaders were imprisoned in El Morro. Historians have called this period the “terrible year of [18]87.” Ten years later, the Spanish government approved the Autonomous Charter, under pressure by the United States, which was threatening to intervene in Cuba.

The main leaders were imprisoned in El Morro. Historians have called this period the “terrible year of [18]87.” Ten years later, the Spanish government approved the Autonomous Charter, under pressure by the United States, which was threatening to intervene in Cuba.

Puerto Rico becomes a U.S. colony

Bombardment of El Morro in the Spanish-American War 1898

Bombardment of El Morro in the Spanish-American War, May 12, 1898

The autonomous government Spain granted did not last long. In February of 1898, the U.S. ship the Maine exploded in Havana Bay, which led to the Spanish-American War. Eight days after the recently inaugurated Puerto Rican Legislature met for the first time, U.S. troops landed at Guánica on July 25, 1898. This marked the end of the Spanish experiment in self-government and inaugurated the U.S. colonial experiment. Although the Island had not participated in the war, its acquisition became part of a new geopolitical vision of U. S. hegemony in the Caribbean. In December of 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed and Spain formally ceded Puerto Rico to the United States. The civil rights and political status of Puerto Ricans would be determined by the U.S. Congress. After more than a century, the control of Puerto Rican sovereignty and its political status remain in the hands of Congress.

S. hegemony in the Caribbean. In December of 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed and Spain formally ceded Puerto Rico to the United States. The civil rights and political status of Puerto Ricans would be determined by the U.S. Congress. After more than a century, the control of Puerto Rican sovereignty and its political status remain in the hands of Congress.

The invading U.S. general, Nelson A. Miles (who was responsible for ending the wars against the Indians in the United States) knew exactly where to land in Puerto Rico. He was well informed of the anti-Spanish sentiment of the people on the southern coast (who had not forgiven the repression of the Compontes of 1887). The surprise landing at Guánica Bay was successful, as the troops were received enthusiastically by the residents of Ponce (stronghold of the island elite) and Yauco (center of Corsicans) while the Spanish army retreated to the mountains. The military campaign in Puerto Rico was quick (the Spanish knew they had already lost Cuba, and thus the war) although some battles continued until the armistice was signed a month after the landing.

What happened next surprised both the liberals and the separatists in Puerto Rico who had welcomed – and even helped – the invasion. They saw the United States as the great democratic country that would give Puerto Rico, as Miles had promised, “the blessings of civilization.” Instead, for two years the United States imposed a military government. When a civil government was established in 1900 through the Foraker Act, U.S. writers such as Lyman Gould and William Tansill still considered it inferior to the Autonomous Charter granted by the Spanish monarchy. In judicial terms, Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory “belonging to the United States but not a part of the United States.” Disappointment with the political status caused open protests and led to a new political organization, the Union Party of Puerto Rico, in 1904. It gathered supporters of autonomy, annexation and independence as the possible ways to define the relationship with the United States. For the first time in Puerto Rican history, independence was included as a legal option in a political party’s program. The Unionists became the dominant party for 20 years, until the rise of a solid Socialist Party (which represented workers and favored statehood) led to alliances and coalitions that prevailed until the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), founded by descendants of the Unionists and other parties, was formed in 1938.

The Unionists became the dominant party for 20 years, until the rise of a solid Socialist Party (which represented workers and favored statehood) led to alliances and coalitions that prevailed until the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), founded by descendants of the Unionists and other parties, was formed in 1938.

First half of the 20th century: Americanization is the goal

Meeting of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico circa 1940

During the first three decades of the 20th century, in a strong effort to Americanize Puerto Ricans, the English language was made obligatory in the public schools. The strategy failed due to the resistance of the population to learn the language. In the 21st century, there are still sectors of the population that resist English and do not speak it, despite government campaigns and the huge influence of the internet and cable television.

Puerto Rico progressed in many aspects during the first decade of U.S. rule: the number of schools increased and health conditions and communications improved. In 1903, the University of Puerto Rico, which had been sought after since the early 19th century, was finally inaugurated. The first steps were the creation of a Normal School, dedicated to educating teachers – in English – to enable the great project of transculturation.

In 1903, the University of Puerto Rico, which had been sought after since the early 19th century, was finally inaugurated. The first steps were the creation of a Normal School, dedicated to educating teachers – in English – to enable the great project of transculturation.

In terms of agriculture, production of subsistence crops declined. A major expansion of sugar cane took place in Puerto Rico, led mainly by three absentee U.S. corporations, which caused an increase in the landless proletariat. This also fed anti-United States sentiment among significant parts of the population. The most important intellectuals of the time, Manuel Zeno Gandía (1855-1930), Luis Lloréns Torres (1876-1844) and Nemesio Canales (1878-1923), wrote about these conditions.

Nationalism

After the beginning of World War I, the geopolitical importance of Puerto Rico to the United States led the Congress to approve the Jones Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to all Puerto Ricans in March, 1917. But feelings of Puerto Ricanness did not disappear with citizenship. These feelings remained especially strong in some sectors of society. The Nationalist Party was founded in 1922 and, under the leadership of Pedro Albizu Campos beginning in 1930, became an instrument of radical resistance. Albizu emphasized Spanish roots and the Catholic religion as protection against Americanization (just as Irish patriots had done when facing the British in Ireland). Albizu’s influence was obvious among the first generation of local writers who emerged under U.S. rule.

But feelings of Puerto Ricanness did not disappear with citizenship. These feelings remained especially strong in some sectors of society. The Nationalist Party was founded in 1922 and, under the leadership of Pedro Albizu Campos beginning in 1930, became an instrument of radical resistance. Albizu emphasized Spanish roots and the Catholic religion as protection against Americanization (just as Irish patriots had done when facing the British in Ireland). Albizu’s influence was obvious among the first generation of local writers who emerged under U.S. rule.

The crisis of the 1930s

It was a period of great social, economic and political crisis, not only in Puerto Rico but in the world. The Great Depression began in 1929, worsening the terrible consequences of Hurricane San Felipe, which had occurred the year before. The situation was appropriately described in the popular song by “Lamento Borincano.” Puerto Rico was known as “the poorhouse of the Caribbean,” after three decades under the U. S. flag. The policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal were extended to the Island to reduce the rampant unemployment and poverty. However, the combination of social strife and strikes, in particular against the sugar industry, and the workers rallies with Albizu, led members of the elite to ask Washington to take a “firm hand” with Puerto Rico. The result was the appointment of the U.S. general Blanton Winship as governor. This appointment provoked a series of violent events that included the assassination of several nationalists by the police in the Río Piedras Massacre in 1935, and the assassination of Police Chief Elisha Riggs by nationalists Elías Beauchamp and Hiram Rosado in 1936. Both were immediately killed by the police. Albizu was arrested and after a questionable trial was imprisoned in Atlanta. These tensions led to what is called the Ponce Massacre in 1937, when armed police, under orders from the governor, opened fire on a protest, which led to 19 deaths, including two police officers, and wounding 235 people.

S. flag. The policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal were extended to the Island to reduce the rampant unemployment and poverty. However, the combination of social strife and strikes, in particular against the sugar industry, and the workers rallies with Albizu, led members of the elite to ask Washington to take a “firm hand” with Puerto Rico. The result was the appointment of the U.S. general Blanton Winship as governor. This appointment provoked a series of violent events that included the assassination of several nationalists by the police in the Río Piedras Massacre in 1935, and the assassination of Police Chief Elisha Riggs by nationalists Elías Beauchamp and Hiram Rosado in 1936. Both were immediately killed by the police. Albizu was arrested and after a questionable trial was imprisoned in Atlanta. These tensions led to what is called the Ponce Massacre in 1937, when armed police, under orders from the governor, opened fire on a protest, which led to 19 deaths, including two police officers, and wounding 235 people. The nationalists were unarmed and were participating in a peaceful march and protest, according to a report by the Hays Commission in the United States. Once Albizu was removed from the political scene, Luis Muñoz Marín, founder of the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), became the main leader in Puerto Rico. The party, which was founded in 1938, controlled politics on the Island for three decades and remains one of the two main parties today.

The nationalists were unarmed and were participating in a peaceful march and protest, according to a report by the Hays Commission in the United States. Once Albizu was removed from the political scene, Luis Muñoz Marín, founder of the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), became the main leader in Puerto Rico. The party, which was founded in 1938, controlled politics on the Island for three decades and remains one of the two main parties today.

The Muñoz era

Luis Muñoz Marín with peasant

The era between 1940 and 1968 brought significant changes to Puerto Rico, which went from being “the poorhouse of the Caribbean” to “the showcase of the Caribbean.” Some writers have referred to these years as “the peaceful revolution.” Puerto Rico went from being an agrarian and rural society to an urbanized and industrialized society with new social classes and many more educational opportunities for the people. To ensure this progress, the government promoted a massive emigration to the continental United States. As expected, the literature of the era reflected these changes. “La carreta” by René Marqués showed the new population changes, including emigration to New York. The conditions of the “neoricans” are described by writers such as José Luis González in his short novel “Paisa” and Pedro Juan Soto in “Spiks.”

As expected, the literature of the era reflected these changes. “La carreta” by René Marqués showed the new population changes, including emigration to New York. The conditions of the “neoricans” are described by writers such as José Luis González in his short novel “Paisa” and Pedro Juan Soto in “Spiks.”

In the 1940s, Puerto Rico’s destiny was once again affected by its strategic importance. During World War II, Puerto Rico was at the center of plans to defend the hemisphere and U.S. military bases appeared throughout the Puerto Rico archipelago, including the islands of Culebra and Vieques. The largest U.S. base in the world was developed in Ceiba, on the east end of the Island, and named Roosevelt Roads.

Second half of the 20th century: the Commonwealth

Women workers in a shoe factory

After the war, the pro-independence faction within the PPD renewed its efforts to fulfill the promises of self-determination for Puerto Rico, while in the United Nations, created in 1945, the Soviet Union (today Russia) and its allies accused the United States of maintaining a colony. As a result, a plan was created with the support of Muñoz Marín to resolve the colonial problem. An intermediate status (neither statehood nor independence) was designed and, after a long process – and the Nationalist Revolt of 1950 – the local constitution was adopted in 1952. It created the Estado Libre Asociado (ELA) in Spanish, a term translated to English as a “commonwealth.” This did not resolve the status question as Muñoz Marín had wanted, but it still defines the political relationships between Puerto Rico and the United States. The debate continues.

As a result, a plan was created with the support of Muñoz Marín to resolve the colonial problem. An intermediate status (neither statehood nor independence) was designed and, after a long process – and the Nationalist Revolt of 1950 – the local constitution was adopted in 1952. It created the Estado Libre Asociado (ELA) in Spanish, a term translated to English as a “commonwealth.” This did not resolve the status question as Muñoz Marín had wanted, but it still defines the political relationships between Puerto Rico and the United States. The debate continues.

The era of alternating power

Luis A. Ferré

In 1968, the PPD lost the elections for the first time in four decades. Luis A. Ferré, who favored the annexation of Puerto Rico to the United States, was elected under the New Progressive Party (PNP) banner. An era of alternating control between the PPD and PNP began. Ferré lost the following election and Rafael Hernández Colón, of the PPD, was elected in 1972. The Hernández Colón administration had to face the worldwide crisis caused by the increase in petroleum prices. As a solution, the federal government granted tax exemptions to multinational corporations that operated in Puerto Rico and extended the federal food stamps program to the Island. The 1970s witnessed the weakening of Operation Bootstrap (the industrialization plan based on U.S. tax exemptions created in 1947) and an increased dependency on federal funds. The economy shifted from manufacturing to high finance based on bank deposits of multinationals. This stage ended when the U.S. Congress eliminated the tax benefits to multinationals (under Section 936 of the federal Internal Revenue Code). In 2006, the benefits fully ended in Puerto Rico. Since then, all administrations have sought a new economic model that would help to ensure a high standard of living.

The Hernández Colón administration had to face the worldwide crisis caused by the increase in petroleum prices. As a solution, the federal government granted tax exemptions to multinational corporations that operated in Puerto Rico and extended the federal food stamps program to the Island. The 1970s witnessed the weakening of Operation Bootstrap (the industrialization plan based on U.S. tax exemptions created in 1947) and an increased dependency on federal funds. The economy shifted from manufacturing to high finance based on bank deposits of multinationals. This stage ended when the U.S. Congress eliminated the tax benefits to multinationals (under Section 936 of the federal Internal Revenue Code). In 2006, the benefits fully ended in Puerto Rico. Since then, all administrations have sought a new economic model that would help to ensure a high standard of living.

Results of the Statehood Yes or No 2020 plebiscite (Source: PR State Elections Commission)

Recent decades of political history in Puerto Rico have been characterized by the exchange of power between the two main political parties (PPD and PNP) and the polarization of society. One sector of Puerto Ricans wants a resolution of the political status, whether statehood, independence or free association with the United States. Another sector wants to maintain the status quo of the commonwealth with certain additional freedoms. Between 1976 and 1984, and from 1992 to 2000, pro-statehood factions controlled the government. However, in the status plebiscites during this era (1993 and 1998), the statehood option did not achieve the majority this sector desired. In 2012, for the first time, a plebiscite returned results favoring statehood. It consisted of two questions: 1, if the voter was in agreement with the current territorial status of Puerto Rico, and 2, which status was favored. On the first, the majority (970,910 or 53.97%) voted that they were not in agreement with the current status. On the second question, 834,191 voters or 61.16% were in favor of statehood. The second question was not answered by 480,918 voters, which was the source of controversy. None of these plebiscites has had a commitment from the U.

One sector of Puerto Ricans wants a resolution of the political status, whether statehood, independence or free association with the United States. Another sector wants to maintain the status quo of the commonwealth with certain additional freedoms. Between 1976 and 1984, and from 1992 to 2000, pro-statehood factions controlled the government. However, in the status plebiscites during this era (1993 and 1998), the statehood option did not achieve the majority this sector desired. In 2012, for the first time, a plebiscite returned results favoring statehood. It consisted of two questions: 1, if the voter was in agreement with the current territorial status of Puerto Rico, and 2, which status was favored. On the first, the majority (970,910 or 53.97%) voted that they were not in agreement with the current status. On the second question, 834,191 voters or 61.16% were in favor of statehood. The second question was not answered by 480,918 voters, which was the source of controversy. None of these plebiscites has had a commitment from the U. S. Congress to accept the decision of the Puerto Rican voters.

S. Congress to accept the decision of the Puerto Rican voters.

During these years, and continuing today, there has been a resurgence in Puerto Ricans’ pride in their culture and identity and a new definition of Puerto Ricanness that has been influenced by the vision of the Puerto Rican community in the United States, the diaspora. This population grew in terms of numbers and political power, including the election of several members of Congress of Puerto Rican origin, representing New York and Illinois.

In the early 21st century, Puerto Rico continues its search for its destiny, with strong ties to the United States, a solid sense of identity and extraordinary artistic and cultural productivity.

References:

Acosta Lespier, Ivonne. “La mordaza: Puerto Rico 1948-1957”. Río Piedras: Editorial Edil, 1987.

Cabrera Salcedo, Lizette. “Reflejos de la historia de Puerto Rico en el arte. San Juan: Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte y Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades, 2016.

Dietz, James. “Historia económica de Puerto Rico”. Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1989.

Moscoso, Francisco. “Fundación de San Juan en 1522”. San Juan: Ediciones Laberinto, 2020.

Moscoso, Francisco y Lizette Cabrera Salcedo. “Historia de Puerto Rico”. San Juan: Ediciones Santillana, 2008.

Rivero, Ángel. “Crónica de la Guerra Hispanoamericana en Puerto Rico”. Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra, 1922.

Robiu Lamarche, Sebastián. “Mitología y religión de los taínos”. San Juan: Editorial Punto y coma, 2006.

Scarano, Francisco. “Puerto Rico: Cinco siglos de historia”. Estados Unidos: Mc Graw Hill, 1993.

Rico – Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia ORT

PUERTO RICO , an island in the Caribbean Sea. Since 1494 it has been a colony of Spain. In 1519, a group of new Christians moved to Puerto Rico, according to some sources, Chuetas (see Shuetas) from the Balearic Islands (see Mallorca). In the future, they all assimilated (see assimilation), but some of their descendants still perform the ritual of lighting candles on Friday evenings (see Kabbalat Shabbat), considering it a family tradition.

In 1898, when Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States, American servicemen and civil administration officials arrived on the island, among whom were several dozen Jews. The resulting community did not last long and disintegrated by 1900, when most American Jews left the island. In 1917, several Jewish families lived in Puerto Rico. In the 1920s a small number of Jews from the United States, French colonies in the West Indies (see Martinique), Cuba and Eastern Europe moved to the island in the 1930s and 40s. – refugees from Germany and the countries occupied by it. At 1926 there were 26 Jewish families on the island, in the early 1940s. — 38. In 1942, the League of Public Services was created, soon renamed the Jewish Community Center of Puerto Rico. At first, it was led by military rabbis from the American units stationed on the island. In 1952, a school was opened at the center, and in 1953, the Ashkenazi (see Ashkenazi) synagogue of the conservative (see Conservative Judaism) Sha’arei Zedek direction, which joined the United Synagogue of America. (1952), attracted several hundred young American Jews to the island. In 1959, after F. Castro came to power in Cuba, 150 Jewish families emigrated from there to Puerto Rico. By the beginning of the 1970s The Jewish population of Puerto Rico reached two thousand (according to other sources – three thousand) people. In 1964, a Jewish cemetery was opened, in 1967, the reformist (see Reformism in Judaism) Bet Shalom synagogue, which became part of the Union of the American Jewish Congregation, was opened.

(1952), attracted several hundred young American Jews to the island. In 1959, after F. Castro came to power in Cuba, 150 Jewish families emigrated from there to Puerto Rico. By the beginning of the 1970s The Jewish population of Puerto Rico reached two thousand (according to other sources – three thousand) people. In 1964, a Jewish cemetery was opened, in 1967, the reformist (see Reformism in Judaism) Bet Shalom synagogue, which became part of the Union of the American Jewish Congregation, was opened.

Despite the decline in the Jewish population (in 1999 – about 1.5 thousand people, of which 90% live in San Juan – the largest city of the island and the capital of the country, the rest in Ponce and Mayagüez), the community of Puerto Rico remains the largest in the Caribbean. Its members – entrepreneurs, directors of industrial enterprises, engineers, scientists, teachers – belong to the upper and middle strata of society. Many Jews of Puerto Rico occupy leading positions in various areas of the country’s life: A. S. Schneider is the head of the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, M. Goldman is the director of the tax office, D. Kelfeld is the dean of the law school of the University of Puerto Rico. Until the end 90-s there were two Jewish schools on the island, after their closure, classes for schoolchildren in Hebrew and the basics of Judaism began to be held in the community center. The Adassah branch X (since 1945), the Bnei Brit lodge (since 1964), the representative office of the United Jewish Appeal, the Young Judea organization are functioning. The community center has the only library in the region with a large selection of books in Hebrew.

S. Schneider is the head of the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, M. Goldman is the director of the tax office, D. Kelfeld is the dean of the law school of the University of Puerto Rico. Until the end 90-s there were two Jewish schools on the island, after their closure, classes for schoolchildren in Hebrew and the basics of Judaism began to be held in the community center. The Adassah branch X (since 1945), the Bnei Brit lodge (since 1964), the representative office of the United Jewish Appeal, the Young Judea organization are functioning. The community center has the only library in the region with a large selection of books in Hebrew.

In the 1950s and 60s there were practically no manifestations of anti-Semitism in Puerto Rico. But return at 1970s–80s many Puerto Ricans from Nicaragua, where many of them worked for Jewish entrepreneurs and adopted the anti-Semitic sentiments of other population groups, have led to a number of anti-Semitic incidents, but their numbers so far remain small.

Contacts between Puerto Rico and Israel are made through US diplomatic agencies.

KEE, volume: 6.

Col.: 900–901.

Published: 1992.

Updated: 04/15/2005.

Soviet Historical Encyclopedia – Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

(Puerto Rico) a country in the West Indies. US possession; according to the constitution of 1952 “a state freely joined the USA”. Includes about. Puerto Rico, as well as the islands of Vieques, Culebra and Mona. Area 8.9 thousand km2. Us., according to an estimate in 1967, 2.7 million people, including Creoles 73%, mulattoes 23%, blacks 4%. State. languages English and Spanish; colloquial Spanish. The predominant religion is Catholicism. The capital is San Juan. Performed power according to the constitution belongs to the governor, elected for 4 years, the legislative congress (Senate and House of Representatives).

In addition to laws approved by Congress, P. -R. US federal laws apply. ETC. represented in the US Congress by a Resident Commissioner with the right to consult. vote.

-R. US federal laws apply. ETC. represented in the US Congress by a Resident Commissioner with the right to consult. vote.

Historical sketch

In the 8th-9th centuries. n. e. P.-R. was settled by the Boriken Indians (the Arawak language group), who migrated to the West Indies from the South. America and named the island Boriken. Borikens were engaged in primitive agriculture, hunting, fishing, weaving, pottery; from metals they knew gold. Later, hosts appeared on the island. the Caribs, who have established themselves here and there on the south and east of the island. By the time the Spanish conquerors (beginning of the 16th century), the Indians were at the stage of the tribal system. Their number, according to various sources, ranged from 50 to 100 thousand people.

Nov 19 1493 during his second trip X. Columbus discovered P.-R. and named it San Juan Bautista in honor of the Spanish. crown prince. Modern name (Spanish Puerto Rico Rich port) the island received from the city, named so in 1508 isp. conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon, under the leadership of which the colonization of the island began. The land, together with the Indians who lived on it, was distributed among the Spaniards. Local residents cultivated the land of their master, worked in mines, building palaces and roads. This system (repartimiento) was later replaced by the encomienda system.

crown prince. Modern name (Spanish Puerto Rico Rich port) the island received from the city, named so in 1508 isp. conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon, under the leadership of which the colonization of the island began. The land, together with the Indians who lived on it, was distributed among the Spaniards. Local residents cultivated the land of their master, worked in mines, building palaces and roads. This system (repartimiento) was later replaced by the encomienda system.

Violence and atrocities of the conquistadors caused a major uprising of the Indians against the conquerors in 1511. By the middle of the 16th century. the local population was almost completely exterminated. In connection with the shortage of labor, importation into P.-R. Negro slaves from Africa, their labor was used on sugar cane plantations. In 1802 Negroes made up 52% of the population of the island. From 1800 to 1825, it means that they moved to the island. the number of white immigrants and by 1845 there were 216 thousand whites and 227 thousand blacks.

After the issuance of a royal decree (1815), which allowed the inhabitants of the island to trade with foreigners, the cultivation of tobacco, sugar cane, ginger, and cattle breeding received some incentive for development. During these years, the expansion of the United States began in P.-R., to-rye considered the island as one of the strongholds for further penetration into the countries of the Caribbean. In the 19th century there were protests against the Spanish. domination (uprisings of 1835, 1838). In 1868, the rebels, led by Ramon Emeterio Betanses, proclaimed a republic in the city of Lares. This is an uprising that went down in the history of P.-R. under the name “Cry from Lares” was brutally suppressed.

In 1897 the island of P.-R. received a curtailed autonomy (the right to send deputies to the Cortes, trade with all countries; expansion of rights in the field of self-government).

During the Spanish-American War of 1898, US troops occupied the island. According to the Paris Peace Treaty, Spain transferred P.-R. together with the small islands adjacent to it to the United States. Amer. gene. John Brook was assigned to the military. governor of the new colony. In May 1900, the US Congress adopted the so-called. Foraker’s act, according to Krom in P.-R. instead of the military, civil was formed. pr-in, an elected body of the House of Representatives was created. However, top. legislator power remained with the US Congress. According to this law, P.-R. was included in the US customs tariff area. The economic ties of the island with the new metropolis increased dramatically.

According to the Paris Peace Treaty, Spain transferred P.-R. together with the small islands adjacent to it to the United States. Amer. gene. John Brook was assigned to the military. governor of the new colony. In May 1900, the US Congress adopted the so-called. Foraker’s act, according to Krom in P.-R. instead of the military, civil was formed. pr-in, an elected body of the House of Representatives was created. However, top. legislator power remained with the US Congress. According to this law, P.-R. was included in the US customs tariff area. The economic ties of the island with the new metropolis increased dramatically.

In P.-R. gushed Amer. capital. During 1910-30, more than half of the peasant proprietors (about 35 thousand people) were expropriated. By 1934 4 Amer. corporations controlled 166,100 acres of land. Deprived of land, the peasants turned into s.-x. and factory workers. Sugar cane has replaced other crops. The development of the island’s economy became more and more one-sided. In 1914, sugar accounted for 63% of exports. of all foreign trade P.-R. belonged to the USA.

In 1914, sugar accounted for 63% of exports. of all foreign trade P.-R. belonged to the USA.

During World War I ca. 18,000 Puerto Ricans were recruited into the Amer. army. On the island, the National guard. At 1917, according to the act of Amer. Senator Jones, in P.-R. A congress was established, consisting of 2 chambers. However, laws he passed could be vetoed by the island’s governor or the US president. 6 ministries were created. However, the governor, as well as officials (prosecutor general, financial controller, members of the Supreme Court, etc.) were appointed by the Amer. president (only since 1947 did the governor of the island begin to be elected by the Puerto Ricans themselves). According to the so-called. Under the Jones Act, all Puerto Ricans born after 1917 became US citizens, and the rest were given a choice. Use money was replaced by American.

World economic the crisis of 1929-33 and the depression that followed had a heavy impact on the economy of P. -R. and the situation of the workers. Prices for basic necessities have skyrocketed. In 1933 a major strike broke out among electricians, and in 1934 among workers in the sugar industry. Increased political the struggle between the forces demanding independence for the island, and their opponents, who advocated the granting of P.-R. US state status. In 1934, in the conditions of a sharp aggravation of the class. struggle was created by the Communist. party P.-R. She actively supported the demands of the workers: improving working conditions, raising wages, introducing social insurance, and led the hunger campaigns of the unemployed. One of the leaders of the national-liberate. movement Albizu Campos, leader of the Nationalist. parties (base 1922), called on Puerto Ricans to arm. fight against the Amer. invaders, which caused a brutal persecution of the party. Oct. 1935 The police staged a massacre of patriots in the city of Rio Piedras. In March 1937, more than 200 Puerto Ricans were killed and wounded in Ponce.

-R. and the situation of the workers. Prices for basic necessities have skyrocketed. In 1933 a major strike broke out among electricians, and in 1934 among workers in the sugar industry. Increased political the struggle between the forces demanding independence for the island, and their opponents, who advocated the granting of P.-R. US state status. In 1934, in the conditions of a sharp aggravation of the class. struggle was created by the Communist. party P.-R. She actively supported the demands of the workers: improving working conditions, raising wages, introducing social insurance, and led the hunger campaigns of the unemployed. One of the leaders of the national-liberate. movement Albizu Campos, leader of the Nationalist. parties (base 1922), called on Puerto Ricans to arm. fight against the Amer. invaders, which caused a brutal persecution of the party. Oct. 1935 The police staged a massacre of patriots in the city of Rio Piedras. In March 1937, more than 200 Puerto Ricans were killed and wounded in Ponce. A wave of raids and arrests swept across the island. A. Campos was sentenced to 12 years. In 1938 the People’s Democratic Party arose. party (NDP), which put forward the task of economic. development of the island. Relying on the support of the United States and the local bourgeoisie, having large finances. means, promising the workers means. improvement of living conditions, it attracted part of the working class and peasantry to its side and won the elections in 1940. During this period in P.-R. a minimum wage was established, a progressive income tax was introduced, a system of measures was developed for the development of industry and with. x-va.

A wave of raids and arrests swept across the island. A. Campos was sentenced to 12 years. In 1938 the People’s Democratic Party arose. party (NDP), which put forward the task of economic. development of the island. Relying on the support of the United States and the local bourgeoisie, having large finances. means, promising the workers means. improvement of living conditions, it attracted part of the working class and peasantry to its side and won the elections in 1940. During this period in P.-R. a minimum wage was established, a progressive income tax was introduced, a system of measures was developed for the development of industry and with. x-va.

In 1943, a law was passed limiting land ownership to 500 acres and alienating surplus land. Within ten years, St. 95 thousand acres of land. However, ok. The 100,000 acres of land subject to alienation still remain in the hands of the landowners, while 200,000 peasants own plots ranging from 0.4 to 1. 7 hectares. A significant part of the page – x. population is completely deprived of land and forced to work for the landowners.

7 hectares. A significant part of the page – x. population is completely deprived of land and forced to work for the landowners.

During World War II, the strategic meaning P.-R. On about. Puerto Rico and the adjacent islands of Vieques and Culebra were created new and strengthened the old Amer. military bases. During the war, 200,000 Puerto Ricans were drafted into the US Army.

The victory over fascism in the 2nd World War was accompanied by a new upsurge of the national liberation. movement. In 1945, 300,000 Puerto Ricans turned to Amer. Congress with a request to allow the inhabitants of the island to decide for themselves the question of the form of government in the country. A similar requirement was contained in a resolution adopted at the beginning. 1946 Congress P.-R. The US government was forced to make some concessions. Yes, Mrs. Spanish was recognized as a language along with English. Under the law of 1947, a Puerto Rican could be elected to the post of governor of the island. In 1948 in P.-R. the first gubernatorial elections were held. The leader of the NDP, Munoz Marin, was elected to this post (re-elected in 1952, 1956, 1960). The economics he outlined measures, as well as special laws passed in 1948 prohibiting participation in the national liberation. movement, could not stop the development of nat.-liberate. fight. Spring 1950 there was a major strike of plantation workers, in which 150 thousand people participated. And in the autumn of 1950 in P.-R. an uprising broke out against US domination, engulfing almost the entire island. All parties, with the exception of the ruling NDP, supported the rebels, who demanded the removal of US troops and an end to the sending of Puerto Rican youths to participate in the war against Korea. Particularly violent clashes occurred in the city of Hayuya, where an independent republic was proclaimed. Using tanks and artillery, Amer. troops brutally crushed the uprising. Thousands of Puerto Ricans, including Gen. Communist Party secretary Santos Rivera and the newly arrested Albizu Campos were thrown into prison.

In 1948 in P.-R. the first gubernatorial elections were held. The leader of the NDP, Munoz Marin, was elected to this post (re-elected in 1952, 1956, 1960). The economics he outlined measures, as well as special laws passed in 1948 prohibiting participation in the national liberation. movement, could not stop the development of nat.-liberate. fight. Spring 1950 there was a major strike of plantation workers, in which 150 thousand people participated. And in the autumn of 1950 in P.-R. an uprising broke out against US domination, engulfing almost the entire island. All parties, with the exception of the ruling NDP, supported the rebels, who demanded the removal of US troops and an end to the sending of Puerto Rican youths to participate in the war against Korea. Particularly violent clashes occurred in the city of Hayuya, where an independent republic was proclaimed. Using tanks and artillery, Amer. troops brutally crushed the uprising. Thousands of Puerto Ricans, including Gen. Communist Party secretary Santos Rivera and the newly arrested Albizu Campos were thrown into prison. Puerto Rican court sentences Albiza Campos to 79years of imprisonment.

Puerto Rican court sentences Albiza Campos to 79years of imprisonment.

In 1952 the United States imposed a new constitution on the island, according to P.-R. was proclaimed “a state freely affiliated with the United States.” After the adoption of the constitution of 1952, the US government informed Gen. Secretary of the United Nations about his decision to stop reporting on P.-R. in the UN due to the fact that this territory allegedly ceased to be “non-self-governing”. 8th session Gen. Assembly of the United Nations (Nov. 1953) proamer. agreed with the US decision by a majority. However, in fact, the island remained a colony under the political, economic. and military US control. In P.-R. continue to operate Amer. laws, US federal law governs legal proceedings, the island retains a single den with the US. system, Puerto Ricans are US citizens but do not have the same rights as Americans. At the same time, on the territory ETC. federal tax legislation does not apply, which is beneficial to the Amer. monopolies.

monopolies.

From the beginning of the 50s. in the country began a campaign for prom. development. Back in 1947, the Congress of P.-R. a law was passed, according to Krom, newly created prom. enterprises were exempted from paying taxes during the first 12 years. This, as well as lower wages than in the United States, contributed to increased inflow into P.-R. foreign, ch. arr. amer., capital; by 1961 the USA had invested in P.-R. 550 million dollars years, more than 500 new industries were created on the island. enterprises. All R. 50s the volume of prom. produced by P.-R. for the first time exceeded the volume of agricultural – x. products (at 1955 56175.3 million dollars of industrial production against 162.1 million dollars of agricultural production. products). The island’s economy is still predominately based. in the production of sugar cane, and the US monopolies control approx. 2/3 economical power and St. 3/4 prom. enterprises. 80% of all cultivated land was taken over by US companies. 2/5 of all s.-x. products began to be imported to the United States. In 1966, the capital investments of the US monopolies exceeded $1 billion. The annual income of the Amer. companies account for 25-30% of the invested capital. At the same time, the wages of Puerto Rican workers are 3 times less than those of US workers. Unemployment is a major problem. In Jan. 1966, according to official. According to the data, there were 104 thousand unemployed (not counting the temporarily unemployed). As a result, annually 50,000 Puerto Ricans emigrate to the United States, where they are subjected to racial discrimination and are employed in the lowest paid jobs.

2/5 of all s.-x. products began to be imported to the United States. In 1966, the capital investments of the US monopolies exceeded $1 billion. The annual income of the Amer. companies account for 25-30% of the invested capital. At the same time, the wages of Puerto Rican workers are 3 times less than those of US workers. Unemployment is a major problem. In Jan. 1966, according to official. According to the data, there were 104 thousand unemployed (not counting the temporarily unemployed). As a result, annually 50,000 Puerto Ricans emigrate to the United States, where they are subjected to racial discrimination and are employed in the lowest paid jobs.

The Americans are actively using the island to pursue an aggressive policy against the socialist. Cuba and other Latin Americans. state-in. 1/8 terr. ETC. busy military. bases (12 bases, including those for launching missiles with atomic charges). Here is Ch. command of the amer. armed forces of the Caribbean zone, the number of Amer. staff is approx. 70 t.h. At 1959, under the influence of the victory of the Cuban revolution, a nat. front “Movement for the independence of P.-R.”, which united all progressive anti-imperialist. strength. The goal of his struggle for democracy. independent state, against the dominance of the Amer. monopolies, militarization of the island, obligatory. conscription, for the creation of an independent anti-imperialist. pr-va, the release of political. prisoners. “Movement” declared (1962) a protest at the UN against the creation on the territory. P.-R., with the permission of the US government, the bases of Cuban counter-revolutionaries for pirate raids on the socialist. Cuba. At 1962, in connection with the intensified struggle of Puerto Ricans for independence, the US government decided to hold in P.-R. plebiscite on the issue of political island status. However, the country’s progressive forces, the P.-R. Independence Movement, the P.-R. Communist Party, Nationalist. party, United Patriotic.

staff is approx. 70 t.h. At 1959, under the influence of the victory of the Cuban revolution, a nat. front “Movement for the independence of P.-R.”, which united all progressive anti-imperialist. strength. The goal of his struggle for democracy. independent state, against the dominance of the Amer. monopolies, militarization of the island, obligatory. conscription, for the creation of an independent anti-imperialist. pr-va, the release of political. prisoners. “Movement” declared (1962) a protest at the UN against the creation on the territory. P.-R., with the permission of the US government, the bases of Cuban counter-revolutionaries for pirate raids on the socialist. Cuba. At 1962, in connection with the intensified struggle of Puerto Ricans for independence, the US government decided to hold in P.-R. plebiscite on the issue of political island status. However, the country’s progressive forces, the P.-R. Independence Movement, the P.-R. Communist Party, Nationalist. party, United Patriotic. action, the United Federation of the Struggle for Independence, and others decided to boycott the plebiscite, considering the plebiscite under the occupation of the island by US troops as an attempt by the US to perpetuate its dominance in P.-R. The intensifying struggle for the independence of P.-R. forced the US Congress on March 1964 to adopt a law on the organization of special. commissions for the study of political. and economic problems P.-R. and the development of a provision on the future status of the island (status quo, either joining the United States as a state, or independence). Nov. 1964 elections for governor and legislator were held. meetings, local authorities, on which the NDP won; R. Sanchez Vilella became governor. Leftist forces boycotted the elections. Student. the demonstration that took place on the eve of the elections and demanded freedom for P.-R. was shot. In the beginning. 1966 more than 1,000 Puerto Ricans were drafted into the army to participate in the Amer.

action, the United Federation of the Struggle for Independence, and others decided to boycott the plebiscite, considering the plebiscite under the occupation of the island by US troops as an attempt by the US to perpetuate its dominance in P.-R. The intensifying struggle for the independence of P.-R. forced the US Congress on March 1964 to adopt a law on the organization of special. commissions for the study of political. and economic problems P.-R. and the development of a provision on the future status of the island (status quo, either joining the United States as a state, or independence). Nov. 1964 elections for governor and legislator were held. meetings, local authorities, on which the NDP won; R. Sanchez Vilella became governor. Leftist forces boycotted the elections. Student. the demonstration that took place on the eve of the elections and demanded freedom for P.-R. was shot. In the beginning. 1966 more than 1,000 Puerto Ricans were drafted into the army to participate in the Amer. war. imperialists in Vietnam. Total by Feb. 1966 in Amer. troops, there were 3.5% of Puertoric. young men, while the population of P.-R. in relation to the US population was 1%. Demonstrations swept across the country against the participation of P.-R. in the Vietnam War. In Aug. 1966 joint commission P.-R. and the United States published a report in which it was said that the average per capita income in P.-R. 40% lower than in the poorest US state. The commission recommended electing a future political leader. the status of the country through a plebiscite under the supervision of the so-called. “Joint Advisory Groups”. Held on July 19The 67th plebiscite was held in the conditions of the occupation of the country by more than 25,000 people. by the US Army, with the active participation in the voting of almost 70 thousand Americans living in P.-R., as well as 30 thousand Cuban counter-revolutionaries located on the island. As a result, 60.5% of those participating in the vote supported the status quo, but more than 1/4 of all voters boycotted the plebiscite.

war. imperialists in Vietnam. Total by Feb. 1966 in Amer. troops, there were 3.5% of Puertoric. young men, while the population of P.-R. in relation to the US population was 1%. Demonstrations swept across the country against the participation of P.-R. in the Vietnam War. In Aug. 1966 joint commission P.-R. and the United States published a report in which it was said that the average per capita income in P.-R. 40% lower than in the poorest US state. The commission recommended electing a future political leader. the status of the country through a plebiscite under the supervision of the so-called. “Joint Advisory Groups”. Held on July 19The 67th plebiscite was held in the conditions of the occupation of the country by more than 25,000 people. by the US Army, with the active participation in the voting of almost 70 thousand Americans living in P.-R., as well as 30 thousand Cuban counter-revolutionaries located on the island. As a result, 60.5% of those participating in the vote supported the status quo, but more than 1/4 of all voters boycotted the plebiscite.

A. P. Moskalenko. Moscow.

Political parties, trade unions and public organizations. People’s Democratic Party created. at 1938. Unites representatives of the majority of the petty, middle and big bourgeoisie, landowners, part of the peasants, workers, students. Closely cooperates with the USA. Opposes essentially against the granting of independence to the country. In the 1964 elections, she won 26 seats out of 32 in the Senate and 52 out of 64 in the House of Representatives. in 1898. In 1903 she joined the US Republican Party and became its regional organization in P.-R. Expresses the interests of the big bourgeoisie and landowners associated with US monopolies. Supports the transformation of P.-R. in one of the US states. Election 1964 won 6 seats in the Senate and 12 in the House of Representatives. Catholic Action Party in 1960. Unites the Catholic. circles of the bourgeoisie and landlords. It relies on the support of part of the peasants, workers and employees. Reflects the interests of the right-wing forces of P.-R. and USA. Independence Party P.-R. created. in 1934. Unites the progressive sections of the petty bourgeoisie, part of the intelligentsia, employees. Enjoys influence among workers and students. Fighting for the transformation of the country into a democracy. republic. Nationalist Party. at 1922. Unites representatives of the petty bourgeoisie, peasants, workers, students. Supports the formation of an independent democracy. republics. Has been illegal since 1937. Actively continues the struggle against the Amer. imperialists, for the independence of the country. Puerto Rican Communist Party in 1934 under the name. Communist Party P.-R. (since 1965, for some time it was called the Workers’ Liberation Party). Fights for an independent democracy. republic. Is in an illegal position.

Reflects the interests of the right-wing forces of P.-R. and USA. Independence Party P.-R. created. in 1934. Unites the progressive sections of the petty bourgeoisie, part of the intelligentsia, employees. Enjoys influence among workers and students. Fighting for the transformation of the country into a democracy. republic. Nationalist Party. at 1922. Unites representatives of the petty bourgeoisie, peasants, workers, students. Supports the formation of an independent democracy. republics. Has been illegal since 1937. Actively continues the struggle against the Amer. imperialists, for the independence of the country. Puerto Rican Communist Party in 1934 under the name. Communist Party P.-R. (since 1965, for some time it was called the Workers’ Liberation Party). Fights for an independent democracy. republic. Is in an illegal position.

Confederation of Independent Puerto Rican Trade Unions cre. in Dec. 1965. A number of societies operate in the country. org-tsy: “Movement for the Independence of P.-R.”, Puerto Rican Peace Committee, Union of Puerto Rican Workers, University Federation of Students, Puerto Rican Socialist. avant-garde and others, who are in favor of improving the social conditions of the population, for the independence of P.-R., and against US aggression in Vietnam.

org-tsy: “Movement for the Independence of P.-R.”, Puerto Rican Peace Committee, Union of Puerto Rican Workers, University Federation of Students, Puerto Rican Socialist. avant-garde and others, who are in favor of improving the social conditions of the population, for the independence of P.-R., and against US aggression in Vietnam.

M. H. Late. Moscow.-***-***-***-

Statistical tables [s]PUERTO RICO_STAT.JPG[/s]-***-***-***-

The most important scientific institutions of P.-R. studying history

Puerto Rican Academy of History in Rio Piedras. Faculty of Social Sciences (Comisión Puertorriqueña de Historia de las Ideas) University P.-P. Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña) in San Juan. The main archive of P.-P. (Archivo General de Puerto Rico) at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture.

Sources and literature for article

Source: Fraga Iribarna M.