Upr puerto rico rio piedras: Universidad de Puerto Rico – Recinto de Río Piedras

University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus

- NEXT

Intro

While I may not be as famous as my North American siblings, I’m hot stuff when it comes to education in Latin America. You can think of me as the friend next door who would invite you over to her quinceañera to meet the family, except this time you get to stay over for four years.

Carpe diem is my motto, and nobody knows that better than my students who really love to party it up. It’s not all fun and games though, being one of the best—if not the best—schools in Latin America requires upholding to certain standards. Yeah, I can be a bit full of myself.

I’m a major university with all those fancy BAs, MAs, and PhDs, so you can count on me to be with you for the long haul if you’re the academic type. I’m well rounded, and can satisfy math nerds, mad scientists, dramatic actors to be, and future best-selling authors.

Also, I have a bit of a European je ne se quoi mixed in with some American entrepreneurship due to my genealogy. This means that I can be a bit old-school, philosophical, and artsy sometimes. Nonetheless my American side helps me keep things real and not let elitism get to my head.

This means that I can be a bit old-school, philosophical, and artsy sometimes. Nonetheless my American side helps me keep things real and not let elitism get to my head.

Name

The Red Rooster

Hometown

Hato Rey in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Also known as the cultural center of the island and home to the best street food. Whether it’s late night poetry or live music, I’ve got it all within five blocks of me. There’s also a train station on campus in case you want to make a quick trip to Old San Juan. Students often kid around by saying that I’m so big, I could be my own city.

Birthdate

1903

Body Type

With around 17,000 students, I’m one of the most attended colleges in the Caribbean. Most of my students are undergrads with a few bookworms here and there focusing on long-term careers in academia. The vast majority of my students are local islanders, so if you’re coming from the mainland, be prepared to be the minority (as well as the center of attention).

Current Living Situation

I’ll be real with you, here in the island we never quite got the whole “it’s college, time to leave home” thing, so a lot of my students actually commute from their parent’s place. For those that do decide to leave the nest, I can offer two residences: one being a rundown building from the 70s, while the other one is a fancy new dorm. When there’s high demand, it’s usually decided via lottery, so may the odds be ever in your favor.

Also, there’s no school cafeteria, so be prepared to get all Julia Childs if you want to save some much needed money.

Relationship Status

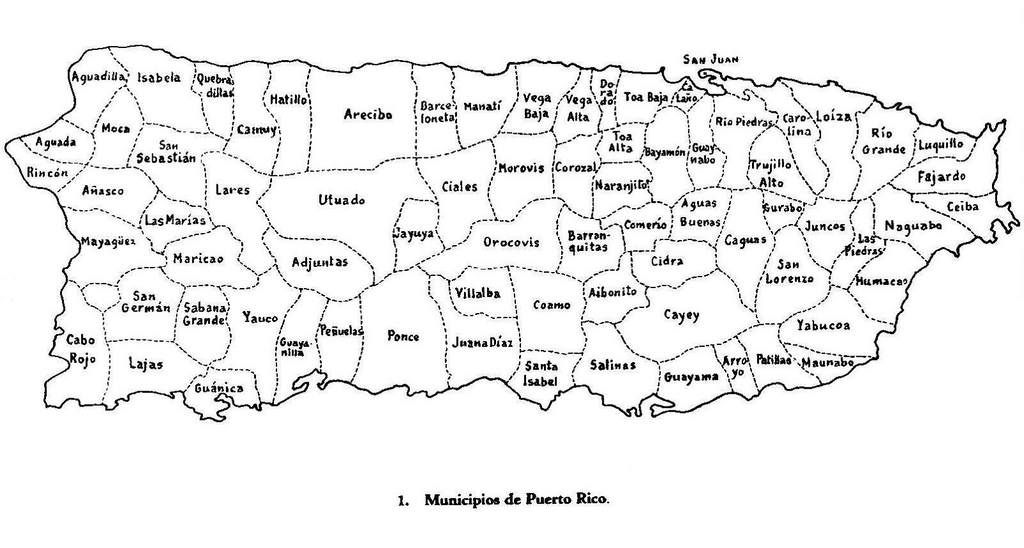

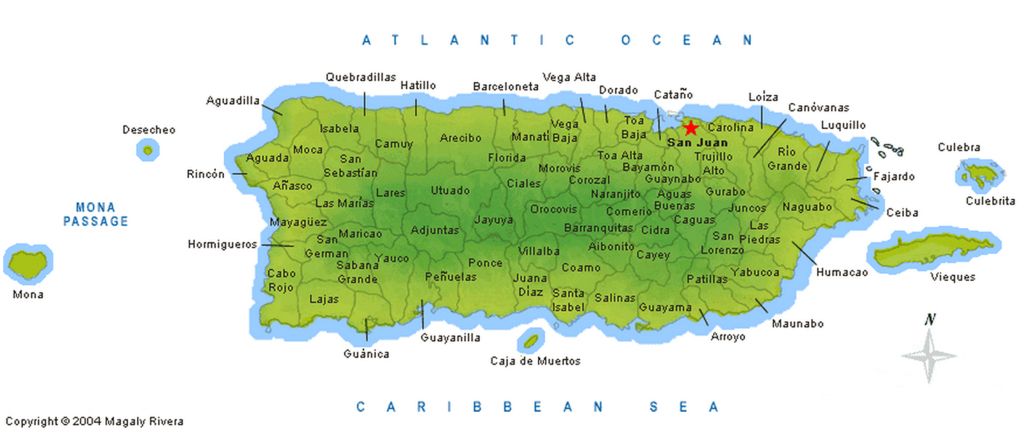

I have a bone to pick with the Inter-American University of Río Piedras. Don’t get me wrong, he’s a nice guy, but he’s a bit stuck up—not at all a cool public institution like me. During the spring break games, competition can be pretty fierce if you get what I’m saying (winner gets a day off school, so all bets are off). My cousin in Mayagüez also tries to steal the spotlight from time to time, but although he’s better at math than me, he just can’t compete with a Jack-of-all-trades like myself.

Politics

I’ll be honest—the European side of my family has captivated my students’ attention more than my American side when it comes to politics. Most students tend to be pretty left-leaning during their first years, and most professors encourage it. Many of my students are advocates for all sorts of rights, and they will fight till the end for what they believe in. This might result in unexpected hiatuses here and then every time there’s a hike in my tuition or a teacher’s strike. Yay or nay? You tell me.

You should apply to me if…

you care more about learning while expanding your horizons than a diploma screaming “Ivy League.”

Website

- NEXT

NCAA Sports

Shmoop your favorite NCAA sport. Baller.

University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Overview

Want the scoop on University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras? We’ve put together a comprehensive report on the school that covers what majors UPR Rio Piedras offers, how the school ranks, how diverse it is, and much more. All you need to do to learn more about a stat is click on its tile, and you’ll be taken to another page that analyzes that data more closely. Also, you can use the links below to scroll to any section of this page.

All you need to do to learn more about a stat is click on its tile, and you’ll be taken to another page that analyzes that data more closely. Also, you can use the links below to scroll to any section of this page.

- Rankings

- Admission and Acceptance

- Faculty

- Retention and Graduation Rates

- Diversity

- Cost

- Student Debt

- Average Earnings

- Location

- Majors

- Online Learning

- Related Schools

How Well Is University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Ranked?

2023 Rankings

College Factual analyzes over 2,000 colleges and universities in its annual rankings and ranks them in a variety of ways, including most diverse, best overall quality, best for non-traditional students, and much more.

University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras was awarded 266 badges in the 2023 rankings.

Overall Quality

According to College Factual’s 2023 analysis, UPR Rio Piedras is ranked #1,210 out of 2,241 schools in the nation that were analyzed for overall quality. This is an improvement over the previous year, when UPR Rio Piedras held the #1,796 spot on the Best Overall Colleges list.

This is an improvement over the previous year, when UPR Rio Piedras held the #1,796 spot on the Best Overall Colleges list.

See all of the rankings for University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras.

Is It Hard to Get Into UPR Rio Piedras?

Acceptance Rate

The acceptance rate at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras is a competitive 49%, so make sure you take your application seriously when putting it together. Even leaving out a minor detail could be a reason to move you to the rejection pile.

Learn more about University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras admissions.

Is UPR Rio Piedras a Good Match for You?

University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Faculty

Student to Faculty Ratio

The student to faculty ratio is often used to estimate how much interaction there is between professors and their students at a college or university. At University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras, this ratio is 15 to 1, which is on par with the national average of 15 to 1. That’s not bad at all.

That’s not bad at all.

Percent of Full-Time Faculty

Another measure that is often used to estimate how much access students will have to their professors is how many faculty members are full-time. The idea here is that part-time faculty tend to spend less time on campus, so they may not be as available to students as full-timers.

The full-time faculty percentage at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras is 72%. This is higher than the national average of 47%.

Full-Time Faculty Percent 72 out of 100

Retention and Graduation Rates at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras

Freshmen Retention Rate

The freshmen retention rate of 84% tells us that most first-year, full-time students like University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras enough to come back for another year. This is a fair bit higher than the national average of 68%. That’s certainly something to check off in the good column about the school.

Freshmen Retention Rate 84 out of 100

Graduation Rate

The on-time graduation rate is the percent of first-time, full time students who obtain their bachelor’s degree in four years or less. This rate is 15% for first-time, full-time students at UPR Rio Piedras, which is lower than the national rate of 33.3%.

This rate is 15% for first-time, full-time students at UPR Rio Piedras, which is lower than the national rate of 33.3%.

On-Time Graduation Rate 15 out of 100

Find out more about the retention and graduation rates at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras.

University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Undergraduate Student Diversity

During the 2017-2018 academic year, there were 10,877 undergraduates at UPR Rio Piedras with 9,543 being full-time and 1,334 being part-time.

How Much Does University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Cost?

The overall average net price of UPR Rio Piedras is $8,183. The affordability of the school largely depends on your financial need since net price varies by income group.

The net price is calculated by adding tuition, room, board and other costs and subtracting financial aid.Note that the net price is typically less than the published for a school. For more information on the sticker price of UPR Rio Piedras, see our tuition and fees and room and board pages.

For more information on the sticker price of UPR Rio Piedras, see our tuition and fees and room and board pages.

Student Loan Debt

It’s not uncommon for college students to take out loans to pay for school. In fact, almost 66% of students nationwide depend at least partially on loans. At UPR Rio Piedras, approximately 6% of students took out student loans averaging $1,805 a year. That adds up to $7,220 over four years for those students.

The student loan default rate at UPR Rio Piedras is 5.1%. This is significantly lower than the national default rate of 10.1%, which is a good sign that you’ll be able to pay back your student loans.

Get more details about paying for University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras.

How Much Money Do UPR Rio Piedras Graduates Make?

Although some majors pay more than others, students who graduate from UPR Rio Piedras with a bachelor’s degree go on to jobs where they make an average salary of $30,290 in their early years. This is about 29% less that the average pay for college graduates overall. However, graduates with your major may make more.

This is about 29% less that the average pay for college graduates overall. However, graduates with your major may make more.

See which majors at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras make the most money.

Location of University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras

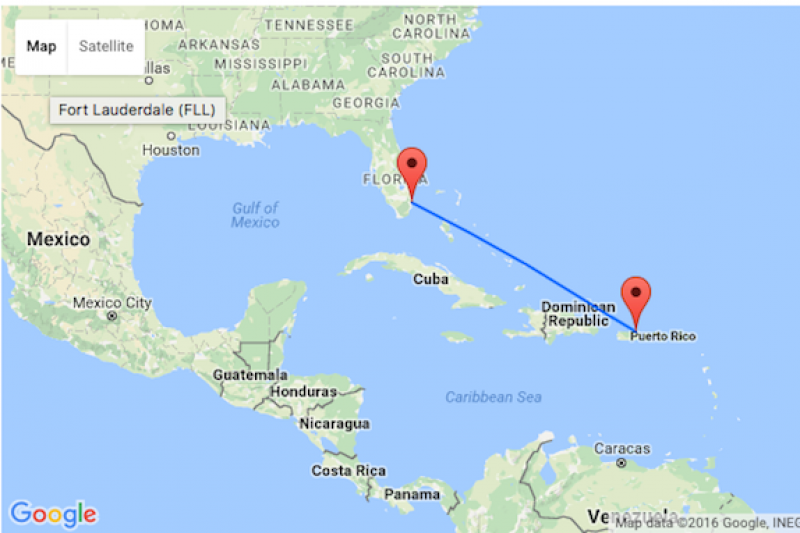

Located in San Juan, Puerto Rico, University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras is a public institution. The city atmosphere of San Juan makes it a great place for students who enjoy having lots of educational and entertainment options.

Get more details about the location of University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras.

Contact details for UPR Rio Piedras are given below.

| Contact Details | |

|---|---|

| Address: | 39 Avenida Ponce De Leon, San Juan, PR 00931-0000 |

| Phone: | 787-764-0000 |

| Website: | www.uprrp.edu/ |

| Facebook: | https://www.facebook.com/uprrp |

| Twitter: | https://twitter. com/uprrp com/uprrp |

University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras Majors

During the most recent year for which we have data, students from 62 majors graduated from University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras. Of these students, 1,803 received undergraduate degrees and 507 graduated with a master’s or doctor’s degree. The following table lists the most popular undergraduate majors along with the average salary graduates from those majors make.

| Most Popular Majors | Bachelor’s Degrees | Average Salary of Graduates |

|---|---|---|

| General Biology | 213 | NA |

| General Psychology | 167 | $12,250 |

| Accounting | 128 | NA |

| Marketing | 101 | $21,004 |

| Linguistics & Comparative Literature | 95 | $20,193 |

| Social Work | 87 | NA |

| Teacher Education Grade Specific | 84 | $16,730 |

| Teacher Education Subject Specific | 75 | $14,325 |

| Human Resource Management | 73 | $21,942 |

| Political Science & Government | 70 | NA |

Learn more about the majors offered at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras along with which ones have the highest average starting salaries.

Online Learning at UPR Rio Piedras

Online learning is becoming popular at even the oldest colleges and universities in the United States. Not only are online classes great for returning adults with busy schedules, they are also frequented by a growing number of traditional students.

In 2019-2020, 376 students took at least one online class at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras. This is an increase from the 10 students who took online classes the previous year.

| Year | Took at Least One Online Class | Took All Classes Online |

|---|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | 376 | 3 |

| 2018-2019 | 10 | 10 |

| 2017-2018 | 5 | 5 |

| 2016-2017 | 3 | 3 |

| 2015-2016 | 5 | 5 |

Learn more about online learning at University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras.

Find Out More About University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras

Notable Rankings

Tuition and Fees

Resources for Veterans

Loan Debt

Sports Programs

Financial Aid

G.

I.® Bill Recepients

I.® Bill Recepients

Return on Investment

If you’re considering University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras, here are some more schools you may be interested in knowing more about.

- Ball State University

- James Madison University

- University of Central Florida

- University of Michigan – Flint

- University of Minnesota – Morris

Curious on how these schools stack up against UPR Rio Piedras? Pit them head to head with College Combat, our free interactive tool that lets you compare college on the features that matter most to you!

report this ad

Notes and References

Footnotes

*The racial-ethnic minorities count is calculated by taking the total number of students and subtracting white students, international students, and students whose race/ethnicity was unknown. This number is then divided by the total number of students at the school to obtain the racial-ethnic minorities percentage.

References

- National Center for Education Statistics

- College Scorecard

- Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

- Image Credit: By Osvaldo Ocasio under License

More about our data sources and methodologies.

Hurricane Maria response in Puerto Rico – News

Brothers Church News Feed

October 20, 2017

Roy Winter, Brothers Disaster Ministries

Lawrence Crepeau, Pastor of Arecibo Brotherhood Church (La Casa del Amigo) , inspects the destruction in the house of his daughter Lorena. Photo by Roy Winter.

After devastating damage from hurricanes like Maria, civil society often falls apart. Desperate or adventurous people begin to rob or steal, and the stress continues to rise. The other part of the society comes together and helps each other, bringing out the best in human nature… and our faith often brings out the best in the church. The churches of Puerto Rico are an inspiring example of how the church is in crisis. Despite many hardships, Puerto Rican brethren come together to support each other and help their communities.

Despite many hardships, Puerto Rican brethren come together to support each other and help their communities.

Already struggling with damage from Hurricane Irma, Puerto Rico was hit by Category 20 Hurricane Maria on September 4, causing widespread destruction, flooding and storm surges. The storm caused catastrophic damage to the island’s power grid, communications towers, crops and poultry, and severely damaged sewage treatment plants, water supplies and roads.

A month later, only 18 percent of homes have electricity, cell phones work on 25 percent of the island, and about half of the island has running water, although it needs to be boiled or cleaned before it can be used. With expected long-term delays in power grid repairs, communication problems and limited water supplies, Puerto Rico’s recovery will be slow and difficult.

In light of this disruption, communication with the Puerto Rico District of the Church of the Brethren was extremely difficult. With the help of the Brethren’s informal network and a recent trip to Puerto Rico, we now know that limited damage has been done to the church structure. In mid-October, I traveled with Puerto Rico District Leader Jose Otero to visit six of the seven churches, pastors, the district council chairman, and several families that had been hit hard. During our time together, we completed this initial church impact assessment and began to formulate recovery plans.

In mid-October, I traveled with Puerto Rico District Leader Jose Otero to visit six of the seven churches, pastors, the district council chairman, and several families that had been hit hard. During our time together, we completed this initial church impact assessment and began to formulate recovery plans.

Puerto Rican Brethren Affected

Currently, 20 Brethren’s homes (some from each congregation) are known to have been badly damaged or flooded. Other houses in all church communities were badly damaged or destroyed. Through the district leadership, a disaster response program is established around each community, needs assessments are conducted, and disaster relief is organized for their communities and affected members.

Several buildings were flooded in the Castagner Brotherhood Church, destroying appliances, floors and furniture, but limited structural damage. In Río Piedras (Caimito), the building of the Segunda Iglesia Cristo Misionera church suffered minor damage, but moderate to severe damage to the roof of the community center and several houses belonging to the church. The remaining five churches reported only minor damage from the storm.

The remaining five churches reported only minor damage from the storm.

Current collaborative disaster management projects between the District and the Brotherhood include:

– A drinking water station is being built at the Rio Prieto Iglesia De Los Hermanos Church for families without access to safe water. It’s in the mountains, miles from safe water sources. Several large water tanks are being installed, which will be filled by tank trucks. Periodic distribution of food is also planned. Castañer Hospital used this church to provide clinics in the region.

– In Caimito (Rio Piedras) at the Segunda Iglesia Cristo Misionera and community center, US work crews will be renovating several houses, the community center and housing for volunteers. Volunteer teams are built by longtime volunteer Brothers Disaster Ministries with funding from the denomination for supplies and volunteer support.

– Each church leader addresses the specific needs of families with damaged homes, medical needs, food/water shortages, and many other issues.

– Container shipped from Brethren’s Service Center with Mid-Atlantic and Southern Pennsylvania Canning Canned Chicken, 14 generators, gas bottles, power cords, chainsaws, carpenter’s tool kit, and Brethren Disaster Management Ministries Saws, 200 pcs. . water. filters and buckets, 200 large heavy tarpaulins and solar lights.

– Funding for a part-time staff member to assist with disaster relief in Puerto Rico.

During my visit, Otero said, “Church members remain positive” and their faith is great. When they visited Judex and Nancy to see how badly their home had been destroyed, their calmness and warm hospitality shone over the damage. It was humiliating when they, like so many with damaged houses, were quick to offer us coffee and a seat when they had so little left. As we visited pastors, we heard all about their members, their congregations, and how they hope to help in recovery. Again, it was humiliating to see leaders so focused on the needs of others.

Like most Puerto Ricans, these pastors and their families face problems with no electricity, no water, and for many, no cell service unless they travel a few miles. Daily life is very hard for everyone, especially for people with health problems and young children. Many also suffer from declining incomes due to job losses, reduced working hours, increased travel times due to damaged roads and destroyed bridges. Simple tasks become more difficult, such as doing laundry by hand, having to communicate with an employer, or having to find cash to buy food.

How to help

About Puerto Rico Brethren Coordinating , the Otero District Executive Director reported that he had limited cell phone access and even less access to email. He asked volunteers, churches, and districts who are planning response programs or want to support Puerto Rico to contact me, Roy Winter, at [email protected] or 410-596-8561. I will try to help him coordinate and report on the response during the weekly planning phone calls we have set up.

Churches in Puerto Rico cannot accept volunteers from the US mainland at this time. . Lack of shelter, electricity, food and water means volunteers are more likely to exacerbate hardship than help. As mentioned above, several self-sufficient groups of volunteers are sent to help with temporary repairs, but these groups cover all their expenses and stay in hotels.

January 13-20 is a work camp led by Shirley Baker. . Brothers Disaster Ministries looks forward to establishing other working groups and possibly a permanent volunteer presence as the leadership of the Puerto Rican church deems it useful. Volunteers interested in the January trip or later programs can contact Terry Goodger at [email protected] or 410-635-8730.

To support disaster relief efforts in Puerto Rico, donate to the Emergency Disaster Relief Fund (EDF) at www.brethren.org/edf.

The Brotherhood Disaster Management Service has requested $100,000 from the Emergency Disaster Relief Fund for a major response in the Caribbean with a focus on Puerto Rico. Brothers Disaster Ministries supports the Puerto Rico County response and the work of each community by providing funds, disaster response experience, response planning, skilled labor and a container of critical materials. This answer will be based on communities focused on the ministry of each Puerto Rican church. The Brethren Disaster Ministries will also attempt to help communicate and coordinate with other Church of the Brethren efforts to support Puerto Rico.

Brothers Disaster Ministries supports the Puerto Rico County response and the work of each community by providing funds, disaster response experience, response planning, skilled labor and a container of critical materials. This answer will be based on communities focused on the ministry of each Puerto Rican church. The Brethren Disaster Ministries will also attempt to help communicate and coordinate with other Church of the Brethren efforts to support Puerto Rico.

– Roy Winter is Associate Executive Director of the Global Mission and Ministry of the Church of the Brotherhood and the Brotherhood in Disaster Management.

Go to www.brethren.org/News Feed to subscribe to the Brethren Church’s free email newsletter and receive Church news every week.

The dark history of birth control pills. Extract from the book “Unhealthy Women”

Fragments of new books

© Bombora Publishing House

Bombora publishes Eleanor Cleghorn’s book on the neglect and prejudice of the female body in Western medicine. TASS publishes an excerpt about the invention of hormonal contraceptives. These drugs allowed women to control their reproductive system, but they were developed not only to give freedom, but also to reduce the birth rate of the poor, uneducated and other people who were considered “inferior”. Pills were also tested on them – several women died

TASS publishes an excerpt about the invention of hormonal contraceptives. These drugs allowed women to control their reproductive system, but they were developed not only to give freedom, but also to reduce the birth rate of the poor, uneducated and other people who were considered “inferior”. Pills were also tested on them – several women died

“Unhealthy women. Why doctors in the past did not want to study the female body and what made them change their minds” is a not quite accurate translation of the original title, in which the historian Eleanor Cleghorn pointed to the root of the problem: from time immemorial, it was mainly men who dealt with women’s health, guided by – albeit not always consciously – prejudices. “Changed” is a strong word. It is known that the bodies of women and men are arranged differently: classic examples are the symptoms of a heart attack and the prevalence of autoimmune diseases that sometimes differ by an order of magnitude. But only recently has it become a requirement to include women in clinical trials, and even then not always: it is enough to open scientific articles on vaccine trials from COVID-19 – no breakdown of results by sex. In his book, Cleghorn tells what this approach has cost for more than two thousand years.

In his book, Cleghorn tells what this approach has cost for more than two thousand years.

The potential of estrogen to free women from sexual problems was discovered in 1960 when the Food and Drug Administration approved Enovid, the first hormonal oral contraceptive. In 1961, British Health Secretary Enoch Powell announced that doctors would be able to get the British equivalent of the drug (Enavid). A small pill made up of synthetic estrogen and progesterone changed the world. For the first time in history, women were able to truly control their own fertility, giving them more time to study, career, and control over their lives and sexuality. They could marry later or not at all, enjoy sex with men without fear of getting pregnant, and not expose themselves to the risks of abortion.

In the early days of oral contraceptives, women had to win the right to take them.

Initially, Enovid and Enavid were cautiously prescribed to relieve menopausal symptoms and menstrual irregularities, including endometriosis. Prevention of pregnancy has been cited as a side effect. Wilson even claimed that no woman who takes Enovid “after childbearing age” will ever “experience menopause.” Family planning clinics provided patients with oral contraceptives, but for money. The British government allowed doctors to decide who to prescribe drugs to; most doctors in the UK and the US only prescribed them to married women for whom pregnancy could be dangerous. At the same time, many were afraid to prescribe drugs not for illness. Most physicians shared the church’s view that oral contraceptives devalue the sacredness of marriage and amount to abortion. Old fears that women’s sexual freedom would lead to the destruction of moral and social values have permeated medical, religious and governmental attitudes towards oral contraceptives since their inception – women’s right to reproductive and sexual autonomy continued to be controlled by public health and the despotic hands of church and state.

Prevention of pregnancy has been cited as a side effect. Wilson even claimed that no woman who takes Enovid “after childbearing age” will ever “experience menopause.” Family planning clinics provided patients with oral contraceptives, but for money. The British government allowed doctors to decide who to prescribe drugs to; most doctors in the UK and the US only prescribed them to married women for whom pregnancy could be dangerous. At the same time, many were afraid to prescribe drugs not for illness. Most physicians shared the church’s view that oral contraceptives devalue the sacredness of marriage and amount to abortion. Old fears that women’s sexual freedom would lead to the destruction of moral and social values have permeated medical, religious and governmental attitudes towards oral contraceptives since their inception – women’s right to reproductive and sexual autonomy continued to be controlled by public health and the despotic hands of church and state.

Since the 1930s, Margaret Sanger has dreamed of an ideal method of contraception: a cheap, harmless, and reliable method that women around the world could use freely. The daily pill proved to be the perfect alternative to the tricky charts, foams and powders that Sanger, in a eugenic fashion, found too difficult for “retarded” women and “slum dwellers.” She hoped the pill would eliminate the need for sterilization, separate sex from reproduction, and, most importantly, be able to be used without the knowledge of a woman’s husband or partner. Early 19In the 1950s, Sanger received a grant from her friend Katherine Dexter McCormick, a biologist and women’s rights activist, for pharmaceutical research on hormonal contraceptives and gave it to Gregory Pincus, an endocrinologist and experimental biologist working in a Massachusetts laboratory. Pincus had to start creating a pill containing progestin, a new synthetic form of progesterone, a female steroid hormone produced by the corpus luteum after ovulation. In 1954, an endocrinologist declared that his drug had all the ingredients needed to be effective, and asked gynecologist John Rock to conduct a small clinical study to see if the drug caused pseudopregnancy in infertile patients.

The daily pill proved to be the perfect alternative to the tricky charts, foams and powders that Sanger, in a eugenic fashion, found too difficult for “retarded” women and “slum dwellers.” She hoped the pill would eliminate the need for sterilization, separate sex from reproduction, and, most importantly, be able to be used without the knowledge of a woman’s husband or partner. Early 19In the 1950s, Sanger received a grant from her friend Katherine Dexter McCormick, a biologist and women’s rights activist, for pharmaceutical research on hormonal contraceptives and gave it to Gregory Pincus, an endocrinologist and experimental biologist working in a Massachusetts laboratory. Pincus had to start creating a pill containing progestin, a new synthetic form of progesterone, a female steroid hormone produced by the corpus luteum after ovulation. In 1954, an endocrinologist declared that his drug had all the ingredients needed to be effective, and asked gynecologist John Rock to conduct a small clinical study to see if the drug caused pseudopregnancy in infertile patients. Rock and Pincus worked in secret as the research and dissemination of contraceptives and pregnancy prevention information continued to be a crime in Massachusetts. However, the Food and Drug Administration was willing to approve oral contraceptives only if a large clinical trial was conducted in women. Therefore, scientists needed to find a legal way to get around the obstacles. “We need a cage with ovulating females to experiment with,” McCormick Sanger wrote.

Rock and Pincus worked in secret as the research and dissemination of contraceptives and pregnancy prevention information continued to be a crime in Massachusetts. However, the Food and Drug Administration was willing to approve oral contraceptives only if a large clinical trial was conducted in women. Therefore, scientists needed to find a legal way to get around the obstacles. “We need a cage with ovulating females to experiment with,” McCormick Sanger wrote.

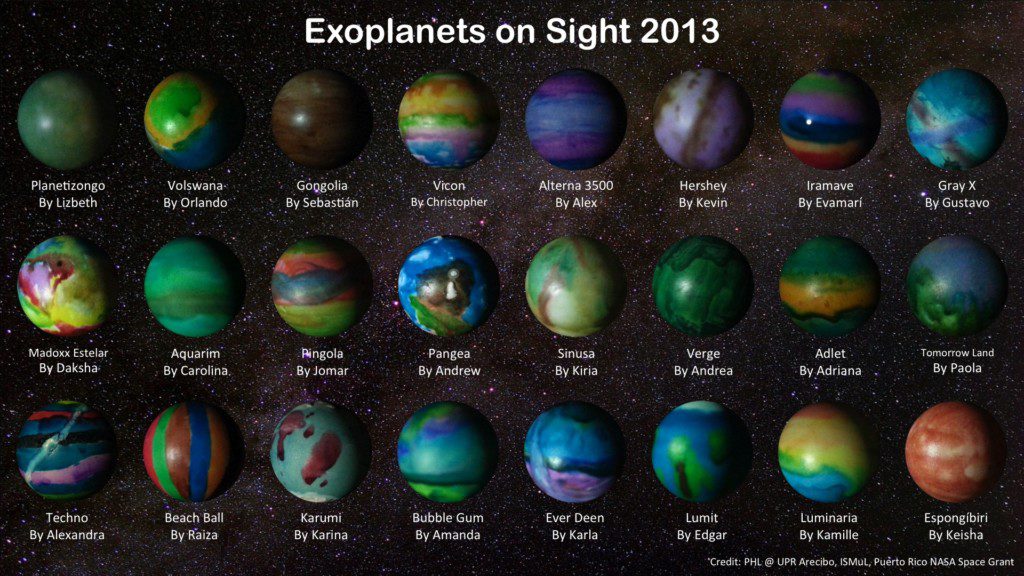

Special project on

Enovid’s first clinical study was conducted in 1956 in one of the most densely populated and impoverished places in the world, Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, which already had a network of family planning clinics. The women living in the new homes of the “slum clearance areas” were the perfect guinea pigs for Pincus and his team, who needed reliable and safe contraceptives. Many women had large families and were forced to resort to sterilization. Since a significant proportion of them could not read or write, the pill regimen had to be simple enough for everyone to follow. Hospital social workers and family planning clinic nurses told the subjects they were being invited to try a new free “anti-fertility drug they couldn’t afford.” Married women under the age of 40 with at least two children were allowed to participate in the study. “We all quickly agreed and never looked back,” said Delia Mestre, one of the participants, 50 years later.

Hospital social workers and family planning clinic nurses told the subjects they were being invited to try a new free “anti-fertility drug they couldn’t afford.” Married women under the age of 40 with at least two children were allowed to participate in the study. “We all quickly agreed and never looked back,” said Delia Mestre, one of the participants, 50 years later.

However, Mestre and hundreds of other women were not told that they were being experimented on. The subjects did not have the opportunity to give informed consent, they were not informed about possible side effects. Their bodies were supposed to show what the side effects could be. By 1958, 830 women living in the suburbs of San Juan, including Rio Piedras and Humacao (a farming region on the island’s east coast), had tried oral contraceptives. Edris Rice-Ray, director of the Puerto Rico Planned Parenthood Association, was responsible for the study. In the first report of a pill trial on 221 women from Rio Piedras at 19In 1957, Rice-Ray noted that 17% of the participants developed symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, gastrointestinal problems, bleeding, vomiting and headaches. She concluded that oral contraceptives “cause too many side effects to be approved for mass use.” However, Pincus and his team chalked up these complaints to the “emotional hyperactivity of Puerto Rican women.” They were only interested in Enovid’s ability to prevent conception. During the study, 17 women became pregnant, but scientists attributed this to improper pill intake. “There was not a single pregnancy that we could explain by the failure of the method,” they wrote. Many women have stopped taking pills due to poor health. According to Pincus, the lowest rejection rate was in Humacao, where the social worker “kept the women in check in every way.”

She concluded that oral contraceptives “cause too many side effects to be approved for mass use.” However, Pincus and his team chalked up these complaints to the “emotional hyperactivity of Puerto Rican women.” They were only interested in Enovid’s ability to prevent conception. During the study, 17 women became pregnant, but scientists attributed this to improper pill intake. “There was not a single pregnancy that we could explain by the failure of the method,” they wrote. Many women have stopped taking pills due to poor health. According to Pincus, the lowest rejection rate was in Humacao, where the social worker “kept the women in check in every way.”

Special project on

Puerto Rican women were considered submissive enough to force them to continuously take an unexplored drug. “Why weren’t we allowed to decide for ourselves?” Mestre was indignant. When mestranol (synthetic estrogen) was added to the mixture of powerful progestins in 1957, Enovid contained three times the amount of estrogen and at least ten times the amount of progestin found in modern combined oral contraceptives. In 1961, a year after the Food and Drug Administration approved Enovid as a contraceptive, reports appeared in the medical press of women in the UK, Los Angeles, and New Jersey who had developed thromboembolism. pulmonary artery or thrombosis. K 19In 1963, 272 such cases and 30 deaths were reported among those who took oral contraceptives. However, the Food and Drug Administration continued to consider Enovid suitable for long-term use. In 1964, Searle, the manufacturer of this drug, was forced to add a warning to the instructions for use that “thrombophlebitis” and “pulmonary embolism” “sometimes happen”, but “no causal relationship between them and the drug was found was”. It later emerged that three women from the Puerto Rican study died suddenly of heart failure and pulmonary embolism. The cases were not described in the results of the study or studied in any way. Autopsies were not performed.

In 1961, a year after the Food and Drug Administration approved Enovid as a contraceptive, reports appeared in the medical press of women in the UK, Los Angeles, and New Jersey who had developed thromboembolism. pulmonary artery or thrombosis. K 19In 1963, 272 such cases and 30 deaths were reported among those who took oral contraceptives. However, the Food and Drug Administration continued to consider Enovid suitable for long-term use. In 1964, Searle, the manufacturer of this drug, was forced to add a warning to the instructions for use that “thrombophlebitis” and “pulmonary embolism” “sometimes happen”, but “no causal relationship between them and the drug was found was”. It later emerged that three women from the Puerto Rican study died suddenly of heart failure and pulmonary embolism. The cases were not described in the results of the study or studied in any way. Autopsies were not performed.

Puerto Rican survey ended in 1964. For seven years, Pincus and his team “tuned” Enovid in experiments on women who did not even know what they were involved in. However, control over the organisms and fertility of Puerto Rican women by medicine and the state did not begin and did not end with oral contraceptives. Pincus’s interest in these means was not social. The scientist did not seek to create support for the life and sexual freedom of women. He was an advocate for scientific intervention and population control.

However, control over the organisms and fertility of Puerto Rican women by medicine and the state did not begin and did not end with oral contraceptives. Pincus’s interest in these means was not social. The scientist did not seek to create support for the life and sexual freedom of women. He was an advocate for scientific intervention and population control.

The racist fear of overpopulation in Hispanic communities has motivated scientists to interfere with the reproductive freedom of Puerto Rican women since the late 1930s, when contraception was legalized and laws were passed allowing eugenic sterilization.

The latter, endorsed and supported by the US government, has been actively promoted as the best way to limit family size. By 1970, about a third of Puerto Rican women had been sterilized, many without their knowledge or consent. La operación (Spanish for “operation”), as it was called, was carried out in hospitals after childbirth, in family planning centers funded by the US government, in birth control clinics for women who worked in factories of American corporations.