Vieques la isla nena de puerto rico: Puerto Rico: Isla Nena, Vieques –

Puerto Rico: Isla Nena, Vieques –

La Isla Nena, llamada así por el poeta puertorriqueño Luis Llorens Torres, conjuga belleza e historia en un terreno de 33 kilómetros de largo por 7.2 de ancho.

La palabra Vieques deriva del lenguaje indo-antillano y significa ‘tierra pequeña’. Para otros autores, proviene de Bieque, cacique taíno que habitaba la isla. Los colonos ingleses de las islas vecinas llamaban a Vieques Crab Island por la abundancia de cangrejos. Sin embargo, Vieques apareció por primera vez en los mapas en 1527 con su nombre actual.

Domina el paisaje el Monte del Pirata (301 metros), al oeste, y el Cerro Matías (138 m.), al este. Rodeando las montañas centrales, pueblan la costa extensas lagunas y pantanos de mangle, así como arrecifes de coral.

Los primeros pobladores de la isla fueron los caribes. Más tarde llegaron colonos franceses (los primeros europeos que ocuparon Vieques), pero el rey de España consideró que Vieques era parte de sus dominios, por lo que los franceses fueron expulsados (1647). Posteriormente llegaron los ingleses, quienes construyeron un fuerte.

Posteriormente llegaron los ingleses, quienes construyeron un fuerte.

La zona urbana y capital de la isla es Isabel II, al norte, frente al antiguo Puerto de Mulas. A lo largo de esta franja costera y hacia el centro y sur se asientan otros núcleos de población, destacando la pequeña villa de Esperanza. Gran parte de Vieques, fundamentalmente la zona oeste, estuvo bajo jurisdicción de la Marina de los EE.UU. (hasta 2003). Actualmente, la gran mayoría de dichos terrenos fueron transferidos a la Agencia Federal de Pesca y Vida Silvestre de los EE.UU.

Aeropuerto Antonio Rivera Rodríguez

Fortin Conde de Mirasol, foto de boavieques

Fortín Conde de Mirasol , Foto de boavieques

Fortín Conde de Mirasol. En Isabel II. Construido en 1845 por orden de Rafael de Aristegui, Conde de Mirasol y gobernador de Puerto Rico, para controlar la entrada y los ataques de franceses e ingleses. Se trata de una pequeña estructura de dos niveles, con techos de vigas y paredes de ladrillo. Las murallas nunca fueron terminadas, pero aún se aprecian sobre una elevada colina de Isabel II. Durante algunos años, desde 1898, sirvió de cárcel estatal.

Las murallas nunca fueron terminadas, pero aún se aprecian sobre una elevada colina de Isabel II. Durante algunos años, desde 1898, sirvió de cárcel estatal.

La Casa del Francés. Construcción histórica de Vieques declarada Monumento Nacional. Antiguamente formó parte de la plantación de caña de azúcar del francés Henri Muraille. Su construcción data de 1910, constituyendo un ejemplo típico de casa campestre de la época. Tras una restauración fue convertida en hotel.

Faro de Punta Mulas. En el Puerto Mulas, Isabel II. Formaba parte de una cadena de faros construidos por el gobierno español (siglo XIX). Es un faro pequeño, compuesto de una torre octogonal de unos 15 metros de altura. Diseñado por el ingeniero militar puertorriqueño José Sanz, sigue el estilo neoclásico e incluye una cornisa que rodea el edificio.

Malecón La Esperanza

La Esperanza. Como Isabel II, fue uno de los primeros asentamientos de Vieques, más tarde convertido en plantación de caña de azúcar. Alberga un pequeño puerto protegido por dos isletas donde se refugian las embarcaciones pesqueras.

Alberga un pequeño puerto protegido por dos isletas donde se refugian las embarcaciones pesqueras.

Bahía Bioluminiscente de Mosquito. Encontramos en Vieques el espectacular fenómeno que producen la concentración de microorganismos bioluminiscentes, que al ser agitados, producen efectos de luz. Debido a las condiciones del área, es una de las bahías bioluminiscentes más espectaculares que se puedan visitar.

Arrecifes de coral. Vieques es un verdadero paraíso para los aficionados al buceo y submarinismo. Los arrecifes de coral son el mayor reclamo de la isla. Entre los más abundantes, destacan los arrecifes de borde, que surgen en las lagunas en contacto directo con la costa, y los arrecifes de mancha, cuyo desarrollo se produce en agrupaciones aisladas de la costa. Los arrecifes de coral en Vieques están más desarrollados en la parte oriental y en la costa norte, entre Punta Este y Punta Mulas, dominando el de tipo borde. En el área occidental, entre Punta Arenas y Punta Boca, viven arrecifes de los dos tipos, también en la costa sur en las entradas de bahías, lagunas y en Ensenada Honda.

Playas de Vieques

Sun Bay

Media Luna, foto de boavieques

La Esperanza

Green Beach/ Punta Arenas

Mosquito bay vista aérea

Playa Grande

Atardecer en Vieques

Para mas información puedes visitar Vieques Events

Quiero agradecer especialmente a mi amigo Oscar conocido como boavieques en flickr y co-adminitrador del grupo en Flickr Isla Nena,Vieques , Gracias por permitirme usar algunas de tus fotos. Los invito a que conozcan su trabajo.

Vieques – Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Coordenadas: 18°07′31″N 65°25′56″O / 18.1252646, -65.4323049

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Ir a la navegaciónIr a la búsqueda

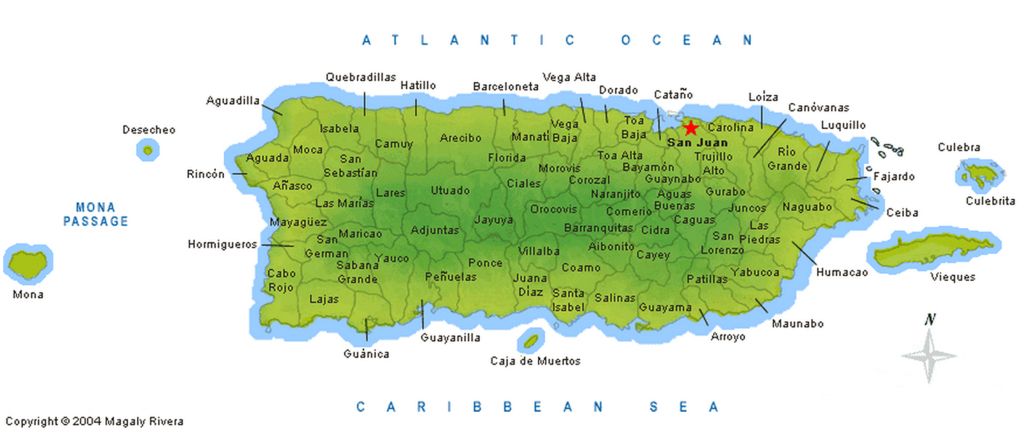

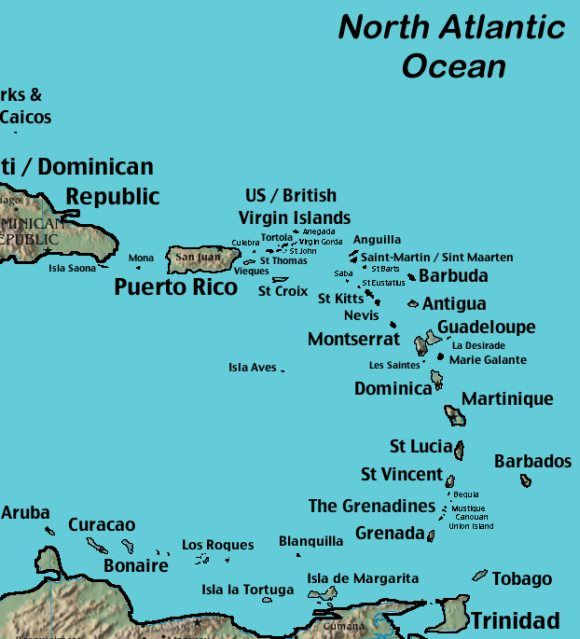

La Isla de Vieques es una isla-municipio del Mar Caribe que forma parte del archipiélago de Puerto Rico, en el noreste del Caribe, que forma parte de un conjunto de islas conocido a veces como las Islas Vírgenes Españolas. La isla está localizada a diez kilómetros al sureste de Puerto Rico (isla principal) y a catorce al sur de la isla-municipio de Culebra. Vieques es parte del estado libre asociado de Puerto Rico.

La isla está localizada a diez kilómetros al sureste de Puerto Rico (isla principal) y a catorce al sur de la isla-municipio de Culebra. Vieques es parte del estado libre asociado de Puerto Rico.

«La Isla Madre, la isla encinta partió en el mar su dolor; La Isla Madre abrió su entraña y la Isla Nena nació.

La Isla Nena, llamada así por el poeta puertorriqueño Luis Llorens Torres, conjuga belleza e historia en un territorio de 33 kilómetros de largo por 7,2 de ancho.

La palabra Vieques deriva del taíno y significa ‘tierra pequeña’. Para otros autores, proviene de Bieque, cacique taíno que habitaba la isla. Los colonos ingleses de las islas vecinas llamaban a Vieques Crab Island por la abundancia de cangrejos. Sin embargo, Vieques apareció por primera vez en los mapas en 1527 con su nombre actual. En la realidad, no hay consenso sobre el origen del nombre, ciertamente taíno.

Domina el paisaje el Monte del Pirata (301 m), al oeste, y el Cerro Matías (138 m), al este. Rodeando las montañas centrales, pueblan la costa extensas lagunas y pantanos de mangle, así como arrecifes de coral.

Rodeando las montañas centrales, pueblan la costa extensas lagunas y pantanos de mangle, así como arrecifes de coral.

Índice

- 1 Historia

- 1.1 La Marina en Vieques

- 2 Geografía

- 3 Véase también

- 4 Referencias

- 5 Enlaces externos

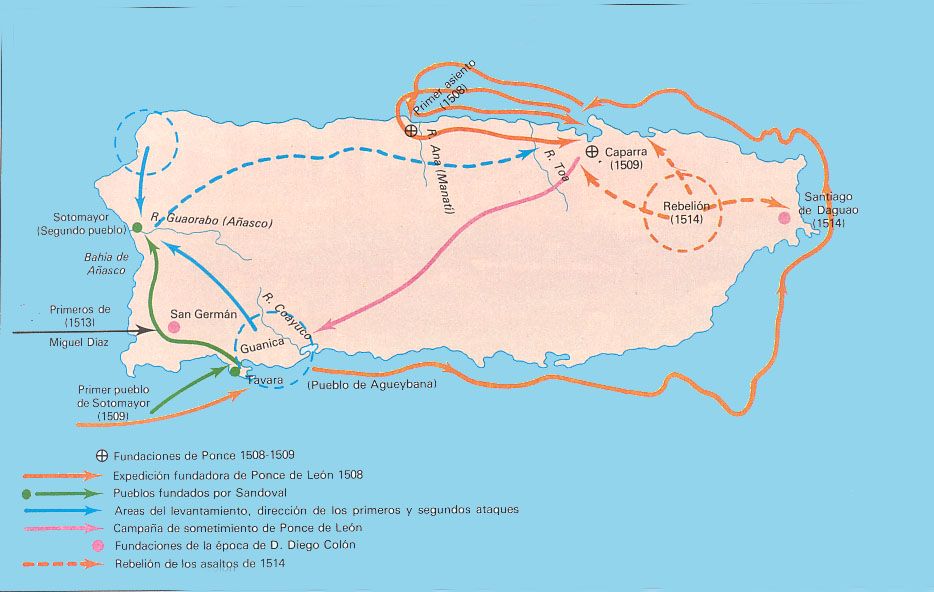

Los primeros pobladores de la isla fueron los taínos. Los primeros colonos en llegar fueron franceses, pero el rey de España consideraba Vieques como parte de sus dominios, por lo que los franceses fueron expulsados (1647). Posteriormente llegaron los ingleses, quienes construyeron un fuerte; pero en 1718 estos también fueron expulsados de la isla.

España ordenó la construcción de un fortín para proteger el territorio ante las reclamaciones de otras naciones europeas. En 1843, se fundó el pueblo de Isabel II (actual barrio capital de Vieques).

Al término de la Guerra hispano-estadounidense (1898), en virtud del tratado de París, Vieques pasó a manos de los norteamericanos y hasta 1952 no formó parte del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico.

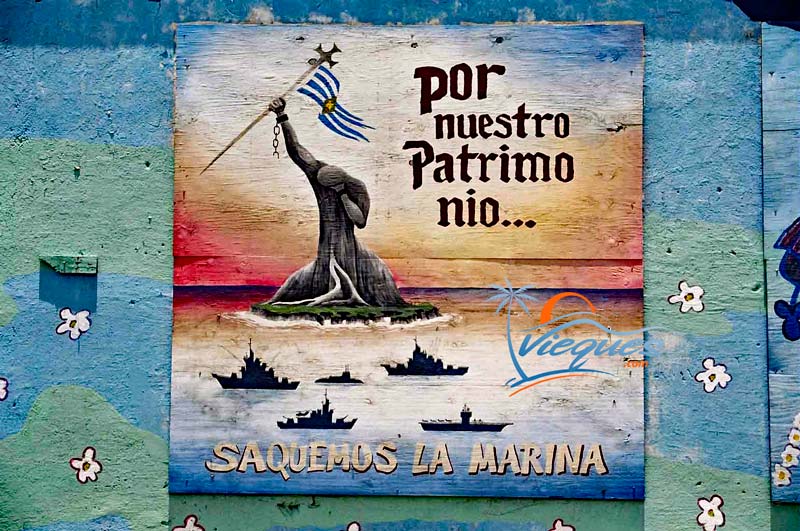

La Marina en Vieques[editar]

La marina estadounidense practicaba maniobras militares en Vieques. Luego de que un guardia de seguridad llamado David Sanes muriese por culpa de una bomba de la marina la gente hizo una lucha social para expulsar a la marina de Vieques. El 1.º de mayo de 2003 por causa de las manifestaciones el ese entonces presidente de los Estados Unidos George Walker Bush en acuerdo con la en ese entonces gobernadora Sila Maria Calderon ordenó que la marina saliese de Vieques.

Sin embargo el gobierno federal estadounidense aseguró su hegemonía en la isla traspasando el poder y control de todo el vasto territorio (66 % de la isla) al Servicio de Pesca y Vida Silvestre hasta el día de hoy.

Vieques vista desde el aire

Véase también: Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Vieques

Vieques mide cerca de 34 kilómetros (21 millas) de este a oeste, y 6 kilómetros (4 millas) de norte a sur. Tiene una superficie de 348. 15 kilómetros cuadrados (134.42 millas cuadradas) y se encuentra a unos 13 kilómetros (8 millas) al este de Puerto Rico. Al norte de Vieques está el Océano Atlántico, y al sur el Mar Caribe. La isla de Culebra está a unos 16 kilómetros (10 millas) al norte de Vieques, y las Islas Vírgenes de EE. UU. se encuentran al este. Vieques y Culebra, junto con varios pequeños islotes, componen las llamadas Islas Vírgenes Españolas, a veces conocidas como las «Islas del Pasaje».

15 kilómetros cuadrados (134.42 millas cuadradas) y se encuentra a unos 13 kilómetros (8 millas) al este de Puerto Rico. Al norte de Vieques está el Océano Atlántico, y al sur el Mar Caribe. La isla de Culebra está a unos 16 kilómetros (10 millas) al norte de Vieques, y las Islas Vírgenes de EE. UU. se encuentran al este. Vieques y Culebra, junto con varios pequeños islotes, componen las llamadas Islas Vírgenes Españolas, a veces conocidas como las «Islas del Pasaje».

Véase también[editar]

- Isla de Culebra

- Islas Vírgenes Españolas

- Islas Vírgenes

Referencias[editar]

Enlaces externos[editar]

- Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Vieques.

- Portal:Puerto Rico. Contenido relacionado con Puerto Rico.

- The Harvard Crimson Clinton, Harvard University’s daily newspaper since 1873, Clinton Disappoints Vieques

- Vieques, Puerto Rico: Documentos de la ATSDR Relacionados con el Campo de Bombardeo

- Fotos de Isla de Vieques

- Historia de Vieques: Cinco Siglos de Lucha de un Pueblo Puertorriqueño, por R.

Rabin, Archivo Histórico de Vieques, divido en dos partes: Historia de Vieques desde el descubrimiento hasta 1930 (I) y Breve Resumen de la Presencia de la Marina de Guerra de Estados Unidos en Vieques y la Lucha del Pueblo por el Rescate de la Isla (II).

Rabin, Archivo Histórico de Vieques, divido en dos partes: Historia de Vieques desde el descubrimiento hasta 1930 (I) y Breve Resumen de la Presencia de la Marina de Guerra de Estados Unidos en Vieques y la Lucha del Pueblo por el Rescate de la Isla (II). - Misterios de la Historia – Capítulo 41: Vieques en YouTube.

- Vieques… 2014 Boricua OnLine.com – Lo Que No Sabía de Puerto Rico y Mucho Más…Isla Nena.

| Control de autoridades |

|

|---|

The main problem was free trade within the empire, liberalization dragged on for twenty years, from the provision of limited benefits to the Windward (Sunda) Islands in 1764 to the free trade agreement 1778, concerning Tierra Firme and extended to New Spain in 1789. An argument in favor of these reforms is the tenfold increase in Catalonia’s exports from 1778 to 1789.year, but in general their influence on the production and entrepreneurial spirit of the Spaniards was minimal. The reforms came too late: Spain no longer had the manufacturing or trading power to win back American markets. As mentioned above, the Spanish fleet was unable to prevent other countries from trading with America. The agreement of 1763 and the negotiations between Britain and Spain in the mid-1760s over the numerous complaints of merchants confirmed this with all evidence. Some in Spain believed that an enlightened monarch should be firm, but the Islas-Malvinas (Falkland Islands) crisis clearly showed the utopian nature of such a position. RELATIONS WITH BRITAIN AND THE THIRTEEN COLONIES Relations between the two countries improved slightly after 1771. Britain eventually decided to vacate Port Egmont in May 1774, and while there was no sign that this was only the first step in resolving the conflict, Spain took the city’s liberation as evidence of London’s goodwill. Later, negotiations began between Britain and Spain over the islands of Vieques near Puerto Rico (the British called it Crab because of the abundance of these crustaceans on the island) and Balambangan (an island north of Borneo), as well as disputes with Portugal regarding military operations in the summer 1776 in Rio de la Plata. The Spanish Ambassador in London presented the note of neutrality on the same day that the border treaty with Portugal was signed. Limits of Bourbon reformism The eighteenth century in Spain is considered a “golden age”, an era of rebirth after a grueling struggle for the legacy of the Spanish Empire, especially its second half, the reign of one of the most enlightened kings in history, Carlos III. The influence of the crown on the situation in the country remained largely limited. In addition, the structure of treasury expenditures, whether in 1731, 1788-1792, 1817 or 1829-1833, did not change: as in the best years of imperial greatness, from 65 to 75% of the treasury funds were allocated to the defense of the kingdom, as a result of which opportunities for investment in new methods of production were rather scarce, and the main recipients of free funds, when they nevertheless formed, were the royal factories specializing in the manufacture of luxury goods (glass, ceramics, tapestries), despite the fact that their products were in demand only 10% the population of the country. Subsistence farming, which was carried out by the remaining 90% of the population, was unable to stimulate demand and create a market for mass consumption; development was also hampered by the supply chain, which was slow and expensive, despite attempts to improve it at the end of the century. Without access to the sea – only Madrid began building a network of roads to meet the needs of the capital and connect the royal residences, and even laid several roads in the north of the peninsula – internal trade stubbornly did not want to increase, and transport was carried out mainly on the backs of mules and donkeys . BREAD ROOTS (1766) The main barriers to development continued to arise in the countryside, from the opposition of privileged owners to the general attitude to change imposed from above, exacerbated by rising land values and rising rents. The first reforms of Carlos III led to a decrease in the incomes of the peasantry, and among the landowners there was talk that ill-conceived measures could cause famine and discontent. EXPLOITATION OF THE JESUITES The situation hastened to be exploited in order to amass political capital; reforming ministers of Carlos III, taking tough measures to suppress the riots and restore public order, as they say, “on the sly” got rid of the Jesuits, who gained too much power by subjugating universities and schools. |

Rabin, Archivo Histórico de Vieques, divido en dos partes: Historia de Vieques desde el descubrimiento hasta 1930 (I) y Breve Resumen de la Presencia de la Marina de Guerra de Estados Unidos en Vieques y la Lucha del Pueblo por el Rescate de la Isla (II).

Rabin, Archivo Histórico de Vieques, divido en dos partes: Historia de Vieques desde el descubrimiento hasta 1930 (I) y Breve Resumen de la Presencia de la Marina de Guerra de Estados Unidos en Vieques y la Lucha del Pueblo por el Rescate de la Isla (II). History of the Country” – Lalaguna Juan – Page 29

History of the Country” – Lalaguna Juan – Page 29 The Spanish Expeditionary Force from Buenos Aires drove the British out of Port Egmont in the spring of 1770. The mission appeared to be successful, but British reaction and the prospect of war, for which the allied France was unprepared, forced the Spaniards to retreat without sufficient guarantees regarding Spanish claims to these islands in the South Atlantic.

The Spanish Expeditionary Force from Buenos Aires drove the British out of Port Egmont in the spring of 1770. The mission appeared to be successful, but British reaction and the prospect of war, for which the allied France was unprepared, forced the Spaniards to retreat without sufficient guarantees regarding Spanish claims to these islands in the South Atlantic. Subsequent negotiations returned the colony of Sacramento (lost during the Seven Years’ War) and seven estates east of the Uruguay River to Spain (boundary treaty March 24, 1778). The appeasement of London was explained by fears about the fate of the English colonies in North America. Prime Minister Lord North acknowledged the inevitable, declaring in the House of Commons in January 1774 that in the end England would have to face the combined fleet of France and Spain. The Bourbons certainly wanted to make the most of Britain’s conflict with the colonies. France decided to support the Thirteen Colonies in February 1778, but Spain offered Britain neutrality in exchange for a series of territorial concessions: first on the list, as usual, was Gibraltar, followed by Menorca, Florida, the Mosquito Coast (Yucatan Peninsula) and settlements in Honduras .

Subsequent negotiations returned the colony of Sacramento (lost during the Seven Years’ War) and seven estates east of the Uruguay River to Spain (boundary treaty March 24, 1778). The appeasement of London was explained by fears about the fate of the English colonies in North America. Prime Minister Lord North acknowledged the inevitable, declaring in the House of Commons in January 1774 that in the end England would have to face the combined fleet of France and Spain. The Bourbons certainly wanted to make the most of Britain’s conflict with the colonies. France decided to support the Thirteen Colonies in February 1778, but Spain offered Britain neutrality in exchange for a series of territorial concessions: first on the list, as usual, was Gibraltar, followed by Menorca, Florida, the Mosquito Coast (Yucatan Peninsula) and settlements in Honduras . The unwillingness of Britain to make concessions forced Spain to start hostilities in June 1778. The peace treaty of 1783 consolidated King Carlos’s foreign policy gains: Spain regained Menorca and West Florida, but not Gibraltar, which successfully repelled a joint Spanish-French attack in 1782. Spain also achieved a clear definition of the boundaries of British possessions in the territory now known as Belize, and the evacuation of British settlements from the Mosquito Coast. On the whole, the last years of the reign of Carlos III seemed quite successful in terms of international relations, but there is no doubt that, by supporting the struggle of the Thirteen Colonies for independence, Spain set a dangerous precedent for its own colonies and that the right to navigate the Mississippi River, inherited from Britain, opened United States way to Mexico.

The unwillingness of Britain to make concessions forced Spain to start hostilities in June 1778. The peace treaty of 1783 consolidated King Carlos’s foreign policy gains: Spain regained Menorca and West Florida, but not Gibraltar, which successfully repelled a joint Spanish-French attack in 1782. Spain also achieved a clear definition of the boundaries of British possessions in the territory now known as Belize, and the evacuation of British settlements from the Mosquito Coast. On the whole, the last years of the reign of Carlos III seemed quite successful in terms of international relations, but there is no doubt that, by supporting the struggle of the Thirteen Colonies for independence, Spain set a dangerous precedent for its own colonies and that the right to navigate the Mississippi River, inherited from Britain, opened United States way to Mexico. Those who hold this opinion blame the disastrous end of the century on the successor to the throne, Carlos IV, and the corrupting influence of the French Revolution. Perhaps French historians, whose contribution to the study of the eighteenth century is enormous, tend to over-praise the era when Spain seemed to be enchanted by French rationality and French style, but it seems that the modernizing and reforming tendencies of the most prominent among the Spanish Bourbons are somewhat exaggerated; moreover, the actions of this king only exacerbated the hardships he sought to overcome. Fateful years, since the execution of Louis XVI in 1793 to the declaration of independence of the Spanish colonies in America in 1824, revealed the unwillingness of those in power to accept change, revealed the weaknesses of the reformers, and were also accompanied by another economic downturn.

Those who hold this opinion blame the disastrous end of the century on the successor to the throne, Carlos IV, and the corrupting influence of the French Revolution. Perhaps French historians, whose contribution to the study of the eighteenth century is enormous, tend to over-praise the era when Spain seemed to be enchanted by French rationality and French style, but it seems that the modernizing and reforming tendencies of the most prominent among the Spanish Bourbons are somewhat exaggerated; moreover, the actions of this king only exacerbated the hardships he sought to overcome. Fateful years, since the execution of Louis XVI in 1793 to the declaration of independence of the Spanish colonies in America in 1824, revealed the unwillingness of those in power to accept change, revealed the weaknesses of the reformers, and were also accompanied by another economic downturn.

On July 15, 1765, a royal decree was issued freeing prices for wheat (it was believed at court that competition would make grain cheaper). At the same time, many settlements were on the verge of starvation after six years of severe drought; by the end of 1765, almost all of Spain was asking the government to intervene urgently, as merchants hid stocks of grain, hoping for an inevitable rise in prices, which reached its peak in March 1766. A riot broke out in Madrid, a frightened Carlos III fled the capital, and the uprising spread to other areas of the kingdom. These protests were repeated regularly throughout the 18th century, increasingly exposing the inability of the Spanish economic system to feed a growing population.

On July 15, 1765, a royal decree was issued freeing prices for wheat (it was believed at court that competition would make grain cheaper). At the same time, many settlements were on the verge of starvation after six years of severe drought; by the end of 1765, almost all of Spain was asking the government to intervene urgently, as merchants hid stocks of grain, hoping for an inevitable rise in prices, which reached its peak in March 1766. A riot broke out in Madrid, a frightened Carlos III fled the capital, and the uprising spread to other areas of the kingdom. These protests were repeated regularly throughout the 18th century, increasingly exposing the inability of the Spanish economic system to feed a growing population.