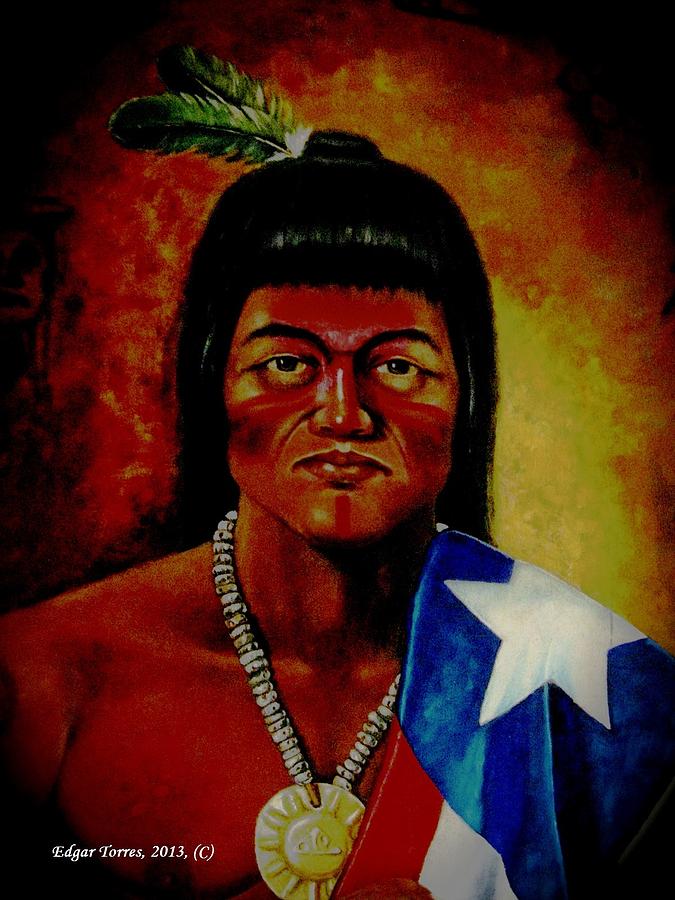

Boricua indian: Indigenous Puerto Rico: DNA evidence upsets established history

The Taína Route and Indigenous Culture in Puerto Rico

Viewpoint of the Río Saliente at Piedra Escrita in Jayuya. In the summer visitors often enjoy a refreshing swim in the river.

Caves, trails, graves, and petroglyphs tell the story of the island’s cultural origins.

The Taíno people populated most of the Caribbean and some adjacent territories during the pre-Columbian era, long before the arrival of Spaniards and others to Puerto Rico.

The island’s indigenous people had a hierarchically structured kingdom, in which each yucayeque or village had a cacique (leader) who ruled and guided their clan. The naborias, or the working class; the nitaínos, the sub-chief; and the bohiques, who were the priests and medicine men, followed their leader and helped build and maintain the social structure.

As part of their religious beliefs, deities were very much present in nature. For example, Yocahú was their supreme creator. Traditions were preserved through ceremonial dances, or areytos, and oral storytelling that took place in the batey, which was the ceremonial plaza also used for sports. The population was highly skilled in hunting and agriculture and made their own utensils from wood or carved rocks, while clothing or hammocks were made of cotton.

Traditions were preserved through ceremonial dances, or areytos, and oral storytelling that took place in the batey, which was the ceremonial plaza also used for sports. The population was highly skilled in hunting and agriculture and made their own utensils from wood or carved rocks, while clothing or hammocks were made of cotton.

After the new conquerors arrived on the Island in the late-15th century, the natives were enslaved and most of them died of diseases or exploitation. Despite all this, Taínos left a profound legacy on Puerto Rico’s culture and its people. Taínos called their home Borinquen, which, translated in English, means “land of the brave lord.” Today, Island locals proudly wear the title of Boricua, an homage to their Island ancestors and traditional culture.

The Taína Route

The Taína Route is an informative tour that highlights the role that this ethnic group had on Puerto Rico’s heritage. From north to south and going through the central mountain areas, the route offers a glimpse into the Taíno’s ceremonial centers, tombs, caves, and petroglyphs. Along the way, you’ll discover that the natives’ contribution to locals’ vocabulary, cuisine, and artwork is undeniable.

Along the way, you’ll discover that the natives’ contribution to locals’ vocabulary, cuisine, and artwork is undeniable.

Caves in Arecibo

Cueva del Indio

Arecibo

Spectacular views of the north coast surround this cave located in a natural reserve in Arecibo, 45 minutes from San Juan. It is thought this was the place where Taínos met to praise their gods, so it is no wonder why it has some of the highest concentrations of petroglyphs in the island. It is a site that is a little tricky to access. Be prepared to walk rocky paths with some elevation changes to access the stunning cavern and cliffs.

Parque Ceremonial Indígena de Caguana, an important Taíno ceremony site.

Plazas in Utuado y Ponce

Centro Ceremonial Indígena Caguana

Utuado

One of the most essential Taíno archaeological sites on the island and a true testament to the indigenous legacy is found in the Centro Ceremonial Indígena Caguana in Utuado, an hour and a half from San Juan in the island’s Central Mountain Range.

The bateyes, 10 plazas, 21 petroglyphs, stoneware and other utensils made by the Taínos can be seen during your visit. You can also explore the nearby river and natural reserve.

While in Utuado, make a stop to visit the indigenous cemetery Joya de Santana to look at the ancient inscriptions on the stones of the Jauca River, or the petroglyphs along the Río Grande de Arecibo, and check out the Cacique Don Alonso monument in the town’s public square.

A petroglyph at the Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Center in Ponce.

Centro Ceremonial Indígena de Tibes

Ponce

Continue along the route to make a stop in Ponce, an hour and a half from San Juan on the southern coastal side of the island, at the Centro Ceremonial Indígena de Tibes, where even more details about life during the Igneri, pre-Taíno, and Taíno cultures are on display in two ceremonial plazas and seven ball fields. Burial sites, petroglyphs, and other articles such as cemíes (carved figures of Taíno divinities), necklaces, and blades made of stone are also part of the exhibit.

Piedra Escrita, in the middle of the Río Saliente, has some of the most incredible petroglyphs.

Jayuya’s Petroglyphs

Piedra Escrita

Route 144, Km. 7.3

In the middle of Río Saliente in Jayuya, almost two hours from San Juan in the mountainous region of the island, you can find one of the most admired petroglyphs in Puerto Rico. La Piedra Escrita is a large carved rock that contains many different types of shapes and forms, such as faces, spirals, and even a coquí. Visitors can swim and play in the water, as well as have direct contact with the rock. There is no fee and a recreational area near the river is open during the day year-round.

Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park in Utuado.

Sol de Jayuya

PR-144

Jayuya has many other Taíno gems that you shouldn’t miss during your visit. El Sol de Jayuya, which is part of the Mural Tallado de Zamas located in Cerro Puntas in the Zamas neighborhood, is one of the most ancient petroglyphs and represents religious signs or symbols such as the god of the sun.

While you’re in town, make a stop at the Museo del Cemí, a cemí-shaped structure located in the Coabey neighborhood where you can enjoy many prehistoric archaeological pieces as well as photographs. The entrance fee to the museum is $1 per person, and it is open from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. all week.

Additional Tips

- Dress comfortably, you will be walking long distances and rocky paths.

- Set enough time apart. It will take you two to three days to explore the whole route.

- Bring your sunscreen and water. The sun in Puerto Rico is intense all-year-round, you’ll need to protect your skin and keep yourself hydrated.

- Bring your swimsuit and be ready to take a dip in the water. There are several opportunities for swimming along the way.

- Ask for help, if you need it. Many hotels have guided tour options available.

- Pack your best smile. You’ll meet many friendly locals along the way. Be ready for the adventure!

View Places Mentioned on a Map

Share this

Tags

History

Culture

Recommended Articles

See All Articles

Kill The Boricua, and Save The Man

By Nestor David Pastor

Learn English. Study medicine, law, or architecture. Find work as a professional. That’s probably what motivated Puerto Ricans families on the island to send their children away to a school in Pennsylvania at the turn of the 20th century. However, they were most likely unaware or disappointed to find out this wasn’t the case. In an article published in 2006 by CENTRO Journal, the academic journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Pablo Navarro-Rivera looks into the controversial history of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School as well as the experience of the Puerto Rican students who attended the school between 1898-1918.

Study medicine, law, or architecture. Find work as a professional. That’s probably what motivated Puerto Ricans families on the island to send their children away to a school in Pennsylvania at the turn of the 20th century. However, they were most likely unaware or disappointed to find out this wasn’t the case. In an article published in 2006 by CENTRO Journal, the academic journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Pablo Navarro-Rivera looks into the controversial history of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School as well as the experience of the Puerto Rican students who attended the school between 1898-1918.

The school was notorious for practicing what its founder Richard Pratt described as “acculturation under duress.” But this is something of an oxymoron. Acculturation doesn’t typically happen under duress. Assimilation is the more familiar, more aggressive manner in which one culture is absorbed completely into another. The terms happen to be used interchangeably, but with acculturation, you’re not necessarily replacing one culture with another.

Click above for additional images.

The Carlisle School, or the CIIC, operated under an ideological framework that classified Native Americans; African-Americans; and beginning in 1898, Puerto Ricans and Cubans; as inferior. This was both a cultural and racial bias. Assimilation, or “acculturation under duress,” was code for saving these people from themselves. At the time, this was also crudely referred to as the “Indian Problem” or the “Negro Problem.” Pratt famously even went as far as to say, “Kill the Indian, and save the man.” Naturally, this extended to Puerto Ricans—who were often lumped in with one group or the other. Navarro highlights some of the confusion, going out of his way to debunk earlier claims that the students selected from Puerto Rico were actually Taíno Indians. Regardless, it didn’t change the nature of the problem or the desire outcome: swap one culture for another.

The CIIS was the flagship institution of a network of schools that sought to ‘Americanize’ its students (Again, this is why it’s important to note the distinction between acculturation and assimilation). There was no effort made to conserve the cultural identity of its students. Quite the contrary, these identities were purposefully stifled for the sake of ‘civilizing’ the students. Boarding schools like the Carlisle existed not only to educate, but also to reeducate.

There was no effort made to conserve the cultural identity of its students. Quite the contrary, these identities were purposefully stifled for the sake of ‘civilizing’ the students. Boarding schools like the Carlisle existed not only to educate, but also to reeducate.

To do this, they developed a three-step program that included: “vocational training, the exposure of students to the dominant model of social and economic organization, and the strenuous imposition of Protestant principles.” It’s also important to remember that students were away from home, not to mention they were banned from speaking any other language besides English. The school went as far as to isolate students from others with a similar cultural background. In addition, the students were closely monitored and followed a strict daily schedule.

Eventually, parents complained. Out of the 60 Puerto Rican students sent to the Carlisle School, eleven withdrew at the request of their parents. Luis Muñoz Rivera, then editor of The Puerto Rican Herald, went on behalf of the parents to investigate their claims. He spoke with some students and concluded that the CIIC was more of a trade school that taught English. This raises the possibility that parents sent their children away under false pretenses.

He spoke with some students and concluded that the CIIC was more of a trade school that taught English. This raises the possibility that parents sent their children away under false pretenses.

However, this is not to say that every Puerto Rican child that attended the CIIS had a bad experience. Navarro profiles several students that look back at their time at the school with pride, gratitude, or even nostalgia. But without sufficient records available, it’s difficult to know what the overall impression was of these 60 students.

Click above for additional images.

Juan José Osuna, who later went on to become a noted educator in Puerto Rico, was one student that was particularly critical of his time at the CIIS. The article he wrote on his experience describes the realization that he wouldn’t be studying law there as he had originally intended. He then left the school, only to be placed with a Welsh family in another Pennsylvania town. Unfortunately, this was just another part of the strategy to assimilate students. The ‘outing system,’ as it was called, encouraged students to not return home and instead, live with a family that could further expose them to the culture.

The ‘outing system,’ as it was called, encouraged students to not return home and instead, live with a family that could further expose them to the culture.

It didn’t work. Despite government support and a righteous sense of cultural superiority, the Carlisle School was a failure. Only 600 of its 10,700 students graduated in a span of 39 years. And of the 60 Puerto Rican students sent, only 7 graduated. As a matter of fact, almost as many Puerto Rican students ran away–five to be exact.

Navarro often compares the CIIS to a molino de piedra, a grindstone that was meant to crush the cultural identity of its students—similar to the approach the U.S. took with public schools on the island. In the end, as Navarro states, “We know little about these young people, participants in the initial stage of what would later be known as the Puerto Rican diaspora.” However, we do know the kind of environment these children faced and the culturally biased views toward Puerto Ricans that have allowed for terms like ‘Americanize’ and ‘assimilation’ to carry the same weight up to and including the present-day.