Indios tainos: What Became of the Taíno? | Travel

Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean | Taíno: herencia e identidad indígena en el Caribe

July 28, 2018–November 12, 2019

New York, NY

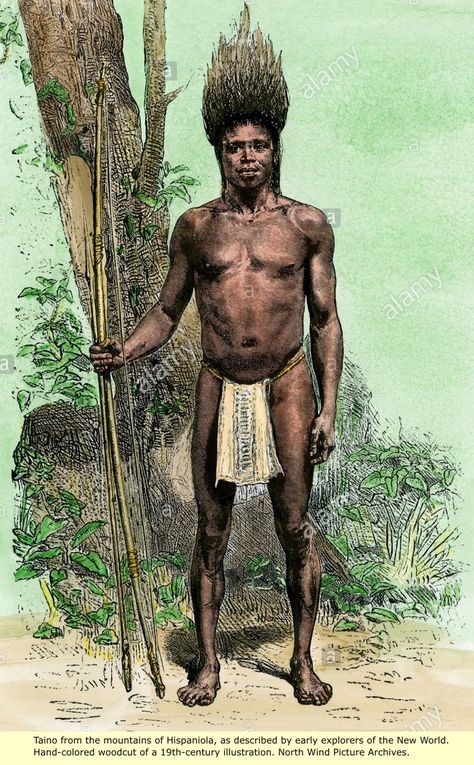

Across the Caribbean, there is growing interest in the historical, cultural, and genetic legacies of Native peoples. In increasing numbers, individuals, families, and organizations are affirming their Native ancestry and identifying themselves as Taíno.

Over the past thirty years, a diverse Taíno movement has taken form. This movement challenges the prevalent belief that Native peoples became extinct shortly after European colonization in the Greater Antilles. It is spurring a regeneration of Indigenous identity within the racially mixed and culturally blended societies of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico, as well as other areas of the Caribbean.

In this exhibition, visitors will explore the rural roots of the Taíno movement and find information about the legacy of Native peoples throughout the Spanish-speaking Caribbean islands and their U. S. diasporas.

S. diasporas.

Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbeanis a collaboration of the National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian Latino Center. This exhibition and related programming are made possible through the support of the Ralph Lauren Corporation and INICIA of the Dominican Republic. Federal support is provided by the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center.

Por todo el Caribe existe un creciente interés en el legado histórico, cultural y genético de los pueblos indígenas. Hay un número cada vez más grande de personas, familias y organizaciones que afirman su ascendencia indígena y se identifican a sí mismas como taínos.

A lo largo de los últimos 30 años se ha conformado un movimiento taíno diverso. Este movimiento cuestiona la creencia predominante de que los pueblos indígenas quedaron extinguidos poco después de la colonización europea en las Antillas Mayores. Está suscitando una regeneración de la identidad indígena dentro de las sociedades mestizas y culturalmente mezcladas de Cuba, la República Dominicana y Puerto Rico, así como de otras áreas del Caribe.

En esta exposición podrá observar las raíces rurales del movimiento taíno y encontrar información acerca del legado de los pueblos indígenas a través de las islas del Caribe de habla hispana y sus diásporas en los Estados Unidos.

Taíno: herencia e identidad indígena en el Caribe es una colaboración entre el Museo Nacional del Indígena Americano y el Centro Latino Smithsonian. La exposición y su programación han sido patrocinados con la generosidad de la Corporación Ralph Lauren e INICIA de la República Dominicana. Apoyo federal ha sido provisto por el Fondo de Iniciativas Latino, administrado por el Centro Latino Smithsonian.

This type of

cemí, known as a cabeza de Macorix, developed on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). It is related to three-corner stone cemis in both design and spiritual function. This one probably represents a Native leader who was venerated after death.

Taíno (Chican Ostionoid) cemi carved to represent a human head, AD 800–1500.

San Pedro de Macorís Province, Dominican Republic. Stone. Purchased in 1941 from A. E. Todd. (20/3511)

San Pedro de Macorís Province, Dominican Republic. Stone. Purchased in 1941 from A. E. Todd. (20/3511)

Este tipo de cemí, conocido como cabeza de Macorix, se desarrolló en la isla de La Española (hoy Haití y la República Dominicana). Se relaciona con el trigonolito tanto en diseño como en función espiritual. Este probablemente representa a un líder indígena quien fue venerado después de morir.

Cemí taíno (chican ostionoide) tallado para representar una cabeza humana, d. C. 800-1500. Provincia de San Pedro de Macorís (República Dominicana). Piedra. Adquirido en 1941 de A. E. Todd. (20/3511)

A Native woman (thought to be Luisa Gainsa) and child near Baracoa, Cuba, 1919. Native communities in eastern Cuba today work with researchers to document their history and culture.

Photo by Mark Raymond Harrington, 1919. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. (N04469)

Una mujer indígena (se cree que es Luisa Gainsa) y una niña, cerca de Baracoa (Cuba), 1919. Comunidades indígenas en el este de Cuba hoy en día trabajan con investigadores para documentar su historia y cultura.

Comunidades indígenas en el este de Cuba hoy en día trabajan con investigadores para documentar su historia y cultura.

Fotografía por Mark Raymond Harrington, 1919. Museo Nacional del Indígena Americano, Institución Smithsonian. (N04469)

Enslavement, resistance, and spirituality connected the cultures and lives of African and Native peoples across the Caribbean. This print depicts enslaved laborers working a sugar plantation on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in the early 1500s.

Illustration from

Naaukeurige versameling der gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indiën … zedert het jaar 1492 tot 1499 (Careful collection of the most memorable sea and land trips to the East and West Indies … dates from 1492 to 1499), published by Pieter van der Aa, 1707. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

La esclavización, la resistencia y la espiritualidad vincularon las culturas y las vidas de los pueblos africanos e indígenas a través del Caribe. Este grabado muestra obreros esclavizados trabajando en una plantación de caña de azúcar en La Española (hoy Haití y la República Dominicana) al comienzo del siglo XVI.

Este grabado muestra obreros esclavizados trabajando en una plantación de caña de azúcar en La Española (hoy Haití y la República Dominicana) al comienzo del siglo XVI.

Ilustración de

Naaukeurige versameling der gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indiën… zedert het jaar 1492 tot 1499 (Colección cuidadosa de los viajes por mar y tierra más memorables a las Indias Orientales y Occidentales… fechas de 1492 a 1499), publicado por Pieter van der Aa, 1707. Cortesía de la Biblioteca John Carter Brown de la Universidad Brown.

The Barrientos family was formed by a Spanish ex-soldier and an Indigenous woman from Baracoa, Cuba, more than 400 years after Spanish colonization.

Photo by Mark Raymond Harrington, 1919. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. (N01404)

La familia Barrientos fue formada por un antiguo soldado español y una mujer indígena de Baracoa (Cuba), más de 400 años después de la colonización española.

Fotografía por Mark Raymond Harrington, 1919. Museo Nacional del Indígena Americano, Institución Smithsonian. (N01404)

Idalis Ramírez Rojas and her daughter, Ingrid, participate in a workshop on local medicinal plants with other Native families from eastern Cuba. Native knowledge is embedded in the rural cultures of the Caribbean.

Photo by the Kaweiro Group, 2015.

Idalis Ramírez Rojas y su hija Ingrid participan en un taller sobre plantas medicinales locales con otras familias indígenas del oriente de Cuba. El conocimiento indígena forma parte íntegra de las culturas rurales del Caribe.

Fotografía por el Grupo Kaweiro, 2015.

Puerto Rican superhero La Borinqueña is shown during a mystical encounter with the powerful deity Yucahu, who appears as a mountain-sized version of a

cemi, a type of ritual object. In the comic, she encounters other Native deities originally described in the 1498 chronicle An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians.

Comic book illustration from

La Borinqueña #1, written and created by Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez. Illustration by Will Rosado and digital colors by Juan Fernández. © 2016 Somos Arte, LLC

La superheroína puertorriqueña La Borinqueña se observa aquí durante un encuentro místico con el poderoso dios Yucahu, que aparece como un cemí (un tipo de objeto ritual) tan grande como una montaña. En el libro de historietas, ella se encuentra con otras deidades indígenas descritas originalmente en la crónica de 1498, Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios.

Ilustración del libro de historietas

La Borinqueña # 1, escrito y creado por Edgardo Miranda Rodríguez. Ilustración por Will Rosado y colores digitales por Juan Fernández. © 2016 Somos Arte, LLC

Los Indios Tainos (Original DR Mix) by Ray MD on Beatport

Track

Link:

Embed:

Artists

Ray MD

- Release 99″ data-ec-variant=”album” data-ec-id=”3591575″ data-ec-d1=”Ray MD, Manybeat, CHRIS TEMPO, DJ Lugo, Davis P” data-ec-d2=”Ray MD, Estephany Hernandez”>

- Length

6:28 - Released

2021-12-20 - BPM

120 - Key

E♭ min - Genre

Afro House

- Label

The Warrior Recordings

People Also Bought

- 29″ data-ec-variant=”album” data-ec-id=”3763384″ data-ec-d1=”Natema, Aaron Sevilla, Valentina Facury”> 29″ data-ec-variant=”album” data-ec-id=”3632800″ data-ec-d1=”Riordan”>

Tú Lo Ve

Ferra Black

Nervous Records

No Hablo Español

Riordan

Candy Flip

Recommended Tracks

- 29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16688954″ data-ec-d1=”Joy Marquez, Zeuqram” data-ec-d3=”Afro House” data-ec-d4=”Afro / Latin”>

Ninos

Lexah Remix 2022Lexa Hill

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16564879″ data-ec-d1=”Elvis Castellano” data-ec-d3=”Afro House” data-ec-d4=”Afro / Latin”>Afro Journey Beats

Original MixRon Trent

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16150956″ data-ec-d1=”Adrian Daboin” data-ec-d3=”Afro House” data-ec-d4=”Afro / Latin”>Tangible

Original MixMemo Rex

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16034100″ data-ec-d1=”KauraDj, Bongotrack” data-ec-d2=”Afronautas” data-ec-d3=”Afro House”>Masai

Luis Erre Invader RemixBongotrack

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16026670″ data-ec-d1=”Jheans Figueroa” data-ec-d3=”Afro House”>La Sabana De La Costa

Original MixIan Justiniani

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”16026649″ data-ec-d1=”Sr. Saco” data-ec-d3=”Afro House”>Nación Shango

Original MixRay MD,

CHRIS TEMPO

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”15985548″ data-ec-d1=”Joy Marquez” data-ec-d3=”Afro House” data-ec-d4=”Afro / Latin”>Amandla

Original MixAaron Sevilla,

dbasser

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”15770269″ data-ec-d1=”Alexander Zabbi, Mr.Drops” data-ec-d3=”Tech House”>Strings

Original MixDavid Morales

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”13791007″ data-ec-d1=”David Tort” data-ec-d2=”Markem, Max Antone” data-ec-d3=”Funky House”>Right On

Original MixSpace Motion

29″ data-ec-variant=”track” data-ec-id=”9765328″ data-ec-d1=”Javier Light, Alberto Dimeo” data-ec-d3=”Tech House”>Walking On Fire

Bedrock Vocal MixEvolution,

Jayn Hanna

Afro Cubano

Original Mix

Joy Marquez,

Zeuqram

Baeidan

Original Mix

Elvis Castellano

Papachongo

Original Mix

Adrian Daboin

Tropa Do BumBum

Afronautas Remix

KauraDj,

Bongotrack

Arabic

Original Mix

Jheans Figueroa

Pirata Africano

Original Mix

Sr. Saco

Palo Santo

Original Mix

Joy Marquez

Tribales

Original Mix

Alexander Zabbi,

Mr.Drops

Hialeah

Markem & Max Antone Remix

David Tort

Groovebeat

Original Mix

Javier Light,

Alberto Dimeo

Thanos Minecraft Fortnite Video game Marvel Comics, Thanos Imperative, television, angle, rectangle png

Thanos Minecraft Fortnite Video game Marvel Comics, Thanos Imperative, television, angle, rectangle png

nine0005 rick,

About this PNG

Image size

- 414x830px

File size

- 101.

18KB

18KB MIME type

- Image/png

Download PNG ( 101.18KB )

resize PNG

width(px)

height(px)

License

Non-Commercial Use, DMCA Contact Us

Marvel Guardians of the Galaxy Groot, Baby Groot Gamora Rocket Raccoon Thanos, rocket raccoon, comics, fictional Characters, carnivoran png

600x600px

52.79KB

nine0006women’s green sleeveless top and black pants, Pom Klementieff Mantis Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. Gamora Nebula 2, marcos mantis, captain, fictional Character, pom Klementieff Mantis png

445x1125px

557.02KBGamora Marvel: Avengers Alliance Thanos Wanda Maximoff Angela, MARVEL, comics, fictional Character, thanos png

820x1469px

579. 43KB

43KBMarvel Star-Lord painting, Chris Pratt Marvel: Avengers Alliance Star-Lord Guardians of the Galaxy Black Panther, chris pine, celebrities, material, shoe png

2000x3958px

1.58MBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Roblox Sword, others, game, angle, text png

1200x1200px

8.73KBThanos Hulk Action & Toy Figures The Infinity Gauntlet Marvel Comics, Charming Villain, comics, fictional Character, mercenary png

480x884px

497.37KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Video game Diamond Sword Minecraft: Story Mode, Season Two, 钻石, angle, rectangle, video Game png

512x512px

11.58KB org/ImageObject”>Thanos Hulk Hot Toys Limited 1:6 scale modeling Action & Toy Figures, Hulk, hulk, thanos, 16 Scale Modeling png

600x600px

80.88KBSuper Mario coin illustration, Super Mario Bros. Super Mario World Minecraft, stack of coins, angle, heroes, super Mario Bros png

2000x2100px

116.99KBGroot Rocket Raccoon Dragon Destroyer Gamora Thanos, guardians of the galaxy, superhero, fictional Character, movies png

564x578px

119.82KBMinecraft: Story Mode Minecraft: Pocket Edition Video game Item, rainforest, angle, text, rectangle png

1024x1024px

24.4KBMinecraft Twitch Video game Computer Servers, treasure chest, angle, rectangle, video Game png

1500x1500px

36.2KB

nine0006Diana Prince Logo Female Sticker, woman, miscellaneous, angle, text png

1600x1600px

23.06KBStar-Lord Gamora Drax the Destroyer Thanos Yondu, Thor, beer, film, breaker png

1058x1600px

981.54KB org/ImageObject”>Minecraft Ender Pearl Purple Video game, peral, purple, blue, angle png

538x538px

11.14KBMinecraft Pixel art Bone, bones, miscellaneous, angle, white png

2600x1200px

80.8KB

nine0006Marvel: Avengers Alliance Thanos Wanda Maximoff Carol Danvers Adam Warlock, guardian of the galaxy, marvel Avengers Assemble, superhero, fictional Character png

576x880px

415.94KBMinecraft Creeper Coloring book Video game Paper, Minecraft, game, angle, white png

1188x1188px

8.15KB org/ImageObject”>green tunnel Super Mario art, Mario Pipe, Plumbing s-, angle, text, rectangle png

705x900px

5.63KBquestion mark, New Super Mario Bros. 2 New Super Mario Bros. 2, block, game, angle, text png

1000x1000px

78.63KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Terraria Minecraft mods, minecraft pixel art unicorn, purple, game, angle png

512x512px

3.68KBBlack Widow Captain America Marvel Comics Symbol, Black Widow, marvel Avengers Assemble, comics, angle png

886x902px

42.44KB org/ImageObject”>Minecraft Coloring book Template Mojang, Minecraft Logo, template, angle, white png

980x980px

8.71KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Sword Mod Lego Minecraft, texture for galaxy, blue, angle, text png

512x512px

45.55KBMinecraft Pickaxe Video game Item Gold, trendy colorful page, angle, white, text png

1600x1600px

16.7KBDrax the Destroyer Marvel: Avengers Alliance Star-Lord Thanos Lego Marvel Super Heroes, marvel destroyer, superhero, marvel, fictional Character png

1024x1024px

425.97KB org/ImageObject”>Benicio del Toro Collector Avengers: Infinity War Grandmaster Thanos, Thor, textile, meme, thanos png

654x1127px

2.81MBMinecraft: Roblox Chestguard Armour, Minecraft, angle, text, rectangle png

539x539px

12.64KBMinecraft mods Sword Xbox 360, minecraft sword, angle, text, logo png

538x538px

10.5KB

nine0006Minecraft mods Iron Man Spider-Man YouTube, skin, avengers, rectangle, video Game png

640x640px

12.1KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Xbox 360 Herobrine Roblox, skin, angle, rectangle, video Game png

516x1050px

22. 6KB

6KBMinecraft Skin Theme Computer Software Computer Icons, others, angle, text, rectangle png

376x767px

42.59KBThanos Funko Collector Action & Toy Figures Marvel Cinematic Universe, guardians of the galaxy, fictional Character, thanos, action Figure png

640x640px

519.26KBTetromino Tetris Polemino Decomino, blocks, miscellaneous, angle, text png

1000x667px

5.55KBCrossword Video game Online book Author, indios americanos, angle, text, rectangle png

771x1019px

9.34KBMinecraft Wall decal Sticker Game, mines, game, angle, white png

1600x1600px

1. 34KB

34KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Mod Item, others, rectangle, orange, diamond png

807x806px

17.47KBMinecraft: Pocket Edition Sword, Minecraft, angle, rectangle, symmetry png

350x450px

71.85KB

nine0006Minecraft Logo Sword Pixel art, others, angle, text, rectangle png

1267x1267px

8.98KBMinecraft The Legend of Zelda Video game Trouble Battery widget, 8-bit heart, game, angle, text png

512x512px

11.28KBRPG Maker MV Tile-based video game Ladder Internet forum, wooden stairs, angle, text, rectangle png

768x576px

297.18KB

Minecraft Paper model Paper model Arcade game, Minecraft Papercraft, template, angle, furniture png

nine08x1283px

13.91KB

nine0087

Clock Minecraft Pixel art Timer Item, Minecraft Heart, rectangle, symmetry, timer png

600x600px

8.41KB

Minecraft: Pocket Edition Deadpool Herobrine Video game, deadpool minecraft skin, game, angle, rectangle png

396x792px

3.25KB

Minecraft: Pocket Edition Carrot Minecraft mods Mojang, carrot slice, game, angle, food png

530x530px

5.67KB

Minecraft Coloring book Video game Skeleton Enderman, minecraft, game, angle, child png

1600x1600px

22.39KB

Minecraft Wall decal Video game Sword, mines, game, angle, white png

1600x1600px

14.21KB

nine0006

Twitch logo, League of Legends Twitch Streaming media, miscellaneous, purple, angle png

500x500px

13.84KB

18KB

18KB 43KB

43KB 6KB

6KB 34KB

34KB