San sebastian martyr: Saint Sebastian | Facts, Feast Day, Patron Saint Of, Tradition, Death, & Art

Gaul | ancient region, Europe

- Major Events:

- Battle of Alesia

- Key People:

- Julius Caesar

Saint Odo of Cluny

Saint Martin of Tours

Severus Alexander

Saint Fursey

- Related Topics:

- Gaul

- Related Places:

- Germany

France

Italy

Europe

Belgium

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

Gaul, French Gaule, Latin Gallia, the region inhabited by the ancient Gauls, comprising modern-day France and parts of Belgium, western Germany, and northern Italy. A Celtic race, the Gauls lived in an agricultural society divided into several tribes ruled by a landed class.

A brief treatment of Gaul follows. For full treatment, see France: Gaul.

By the 5th century bc the Gauls had migrated south from the Rhine River valley to the Mediterranean coast. By the middle of the 4th century bc various Gallic tribes had established themselves across northern Italy from Milan to the Adriatic coast. The region of Italy occupied by the Gauls was called Cisalpine Gaul (“Gaul this side of the Alps”) by the Romans. In 390 bc the Gauls seized and plundered the city of Rome. This humiliation helped to inspire the Romans’ drive to conquer Gaul. The Cisalpine Gauls pushed into central Italy by 284. In a series of confrontations, the Romans defeated the tribe of the Insubres, took Milan, and established colonies in a buffer zone. In the Second Punic War, Hannibal of Carthage made an alliance with the Gallic Cenomani against the Romans; the Romans prevailed, however, and by 181 Rome had subjugated and colonized Cisalpine Gaul.

By the 2nd century bc, when the Romans extended their territory across the Alps into the south of France, they already controlled most of the commerce in that part of the Mediterranean. An alliance with the Aedui against the Allobroges and the Arverni brought the Romans control of the Rhône River valley after 120 bc. The Roman colony of Narbo Martius (Narbonne) was founded on the coast in 118, and the southern province became known as Gallia Narbonensis. An invasion by Germanic Cimbri and Teutones was defeated by Marius in 102, but 50 years later a new wave of invasions into Gaul, by the Helvetii from Switzerland and the Suevi from Germany, triggered Roman conquest of the rest of Gaul by Julius Caesar in 58–50 bc.

An alliance with the Aedui against the Allobroges and the Arverni brought the Romans control of the Rhône River valley after 120 bc. The Roman colony of Narbo Martius (Narbonne) was founded on the coast in 118, and the southern province became known as Gallia Narbonensis. An invasion by Germanic Cimbri and Teutones was defeated by Marius in 102, but 50 years later a new wave of invasions into Gaul, by the Helvetii from Switzerland and the Suevi from Germany, triggered Roman conquest of the rest of Gaul by Julius Caesar in 58–50 bc.

During 53–50 Caesar was engaged in suppressing a Gallic revolt led by Vercingetorix. He treated the Gauls generously, leaving their cities with a significant measure of autonomy, and thus secured the allegiance of Gallic soldiers in his civil wars against Pompey in 49–45. A former religious centre of Gallic society, Lugdunum (Lyon) became the capital of Roman Gaul. The country was divided into four provinces: Narbonensis, Aquitania to the west and south of the Loire, Celtica (or Lugdunensis) in central France between the Loire and the Seine, and Belgica in the north and east. The Romans built towns and roads throughout Gaul and taxed the old Gallic landowning class while promoting the development of a middle class of merchants and tradesmen. The emperor Tiberius was obliged to suppress a rebellion of the nobles in 21 ad, and the assimilation of the Gallic aristocracy was secured when the emperor Claudius (41–54 ad) made them eligible for seats in the Roman Senate and appointed them to governing posts in Gaul.

The Romans built towns and roads throughout Gaul and taxed the old Gallic landowning class while promoting the development of a middle class of merchants and tradesmen. The emperor Tiberius was obliged to suppress a rebellion of the nobles in 21 ad, and the assimilation of the Gallic aristocracy was secured when the emperor Claudius (41–54 ad) made them eligible for seats in the Roman Senate and appointed them to governing posts in Gaul.

The next two centuries were marked by occasional revolts, by increasingly frequent invasions of Germanic tribes, against whom a line of limes, or fortifications, was erected from the middle Rhine to the upper Danube, and by the introduction of Christianity early in the 2nd century. During the reign of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (161–180), Germanic invaders crossed the limes. Frontier legions rebelled along the Rhine, spurring the civil wars that followed the death of the emperor Commodus in 192. An economic recession, marked by inflation and rising prices, hurt the towns and the small farmers.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Subscribe Now

In 260 Gaul, Spain, and Britain formed an independent Gallic empire, governed from Trier. The emperor Aurelian reclaimed Gaul for Rome in 273, but Germanic tribes devastated the country as far as Spain. Under Diocletian and his successors, reforms in defense and administration were instituted, but Gaul became a centre of the unrest that was fragmenting the empire. In the middle of the 4th century the tide of invasions swelled. By the 5th century the Visigoths had taken Aquitania, the Franks ruled Belgica, and the Burgundians dominated the Rhine. By the time the kingdom of the Frankish Merovingians arose, in the early 6th century, the Romans had lost control of Gaul.

In the end, Gaul proved to be an important repository of Roman culture. Gallic writers long kept the classical Roman literary tradition alive. Many of the amphitheatres, aqueducts, and other Roman works built in Gaul still stand.

404 File Not Found

We ask you, humbly, to help.

Hi readers, it seems you use Catholic Online a lot; that’s great! It’s a little awkward to ask, but we need your help. If you have already donated, we sincerely thank you. We’re not salespeople, but we depend on donations averaging $14.76 and fewer than 1% of readers give. If you donate just $5.00, the price of your coffee, Catholic Online School could keep thriving. Thank you. Help Now >

The requested URL /saints/saint.php%3fsaint_id%3d103 was not found on Catholic Online (www.catholic.org).

We are sorry, but the page you were looking for can’t be found. Don’t worry though, use the search below to find what you are looking for.

Search Search Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don’t just join an email list – you’re joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Email Address

Saint of the Day for Thursday, Dec 22nd, 2022

Saint of the Day for …

Mysteries of the Rosary

Mysteries of the Rosary

Female / Women Saints

Female / Women Saints

Popular Prayers

Popular Prayers

St. Chaeromon

St. Chaeromon

Prayer of the Day for Thursday, Dec 22

Prayer of the Day for …

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

7 Morning Prayers you need to get your day started with God

7 Morning Prayers you need to …

Bible

Bible

The Apostles’ Creed

The Apostles’ Creed

Catholic PDFs – Print – FreeLight a Virtual Prayer Candle

Love is Born on Christmas Morn, and the World is Born Anew

Advent Reflection – Day 25 – The Fourth Wednesday of Advent

Sorry, Catholic Online School is Not for Sale

Advent Reflection – Day 24 – The Fourth Tuesday of Advent

How to Handle Christmas Stress

Daily Catholic

- Daily Readings for Thursday, December 22, 2022

- St.

Chaeromon: Saint of the Day for Thursday, December 22, 2022

Chaeromon: Saint of the Day for Thursday, December 22, 2022 - Advent Prayer #2: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, December 22, 2022

- Daily Readings for Wednesday, December 21, 2022

- St. Peter Canisius: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, December 21, 2022

- Advent Prayer: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Never Miss any Updates!

Saints & Angels

- Saints Feast Days

- Female Saints

- Saint of the Day

- Browse Saints

- Popular Saints

- Patron Saints

- Saint Fun Facts

- Angels

- Martyr Saints

- More Saints & Angels

Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Stations of the Cross

- Guide for Confession

- Prayer of the Day

- Browse Prayers

- Popular Prayers

- Holy Rosary

- Sacraments of the Catholic Church

- More Prayers

Bible

- Daily Readings

- New Testament

- Old Testament

- Books of the Bible

- Ten Commandments

- More Bible

More of Catholic Online

- Lent & Easter

- Advent & Christmas

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Calendar

- All of Catholic Online

2022 is almost over, and we still need your support

youtube.com/embed/qMEB83pVQ_c/?rel=0″ title=”2022 is almost over, and we still need your support” frameborder=”0″>

This Christmas Season, we humbly ask you to join the 2% of readers who give. If everyone reading this right now gave just $5, we’d hit our annual goal in a couple of hours. The price of a cup of coffee is all we ask.

Give Now

- Contact Us

- Privacy Statement

- Terms of Service

Copyright 2022 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2022 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

A story of art in one story: Saint Sebastian • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

- History

- Art

- Literature

- Anthropology

I’m lucky!

Art, History

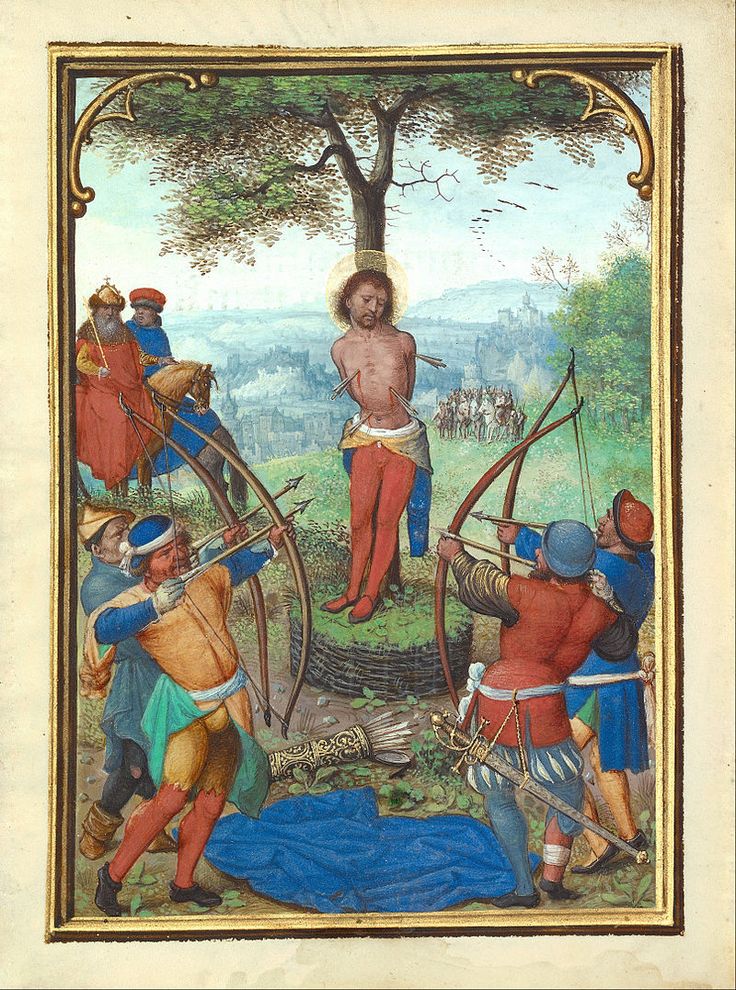

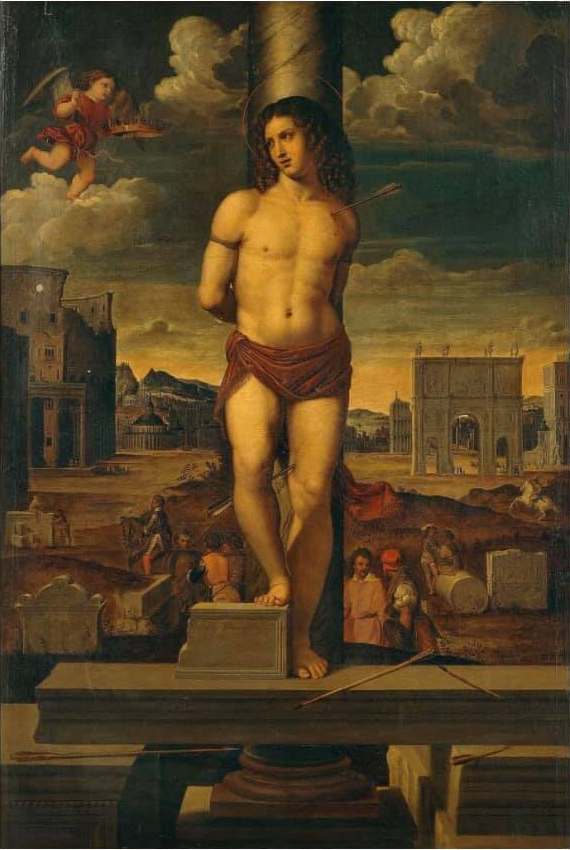

How a Roman military leader-Christian turned from a middle-aged bearded martyr into a gay icon

Author Anna Kiseleva

Saint Sebastian is one of the most famous Catholic saints. In the early Middle Ages, he was revered as a martyr who did not betray the faith and worthily accepted death in the name of Christ, and from the end of the 14th century, after the plague that struck all of Europe in the middle of the century, as a protector from this disease. Sebastian was executed when he was about thirty years old, and little is known about his life. The brevity of the biography influenced the iconography of the saint: the artists were mainly impressed by the story of his execution and the plots connected with it, and not by the stories about how the Roman legionnaire Sebastian converted his fellow soldiers to Christianity. nine0004

The brevity of the biography influenced the iconography of the saint: the artists were mainly impressed by the story of his execution and the plots connected with it, and not by the stories about how the Roman legionnaire Sebastian converted his fellow soldiers to Christianity. nine0004

Thanks to Saint Ambrose, Bishop of Milan and theologian, we know that Sebastian was born in Milan and died in Rome. We know more details (although few of them) thanks to the Golden Legend, a medieval collection of the lives of the saints, compiled in the 13th century by the monk Jacob Voraginsky, later the archbishop of Genoa. Sebastian was born in Narbonne, lived in Rome under the emperor Diocletian (284-305), served as the head of the guard and secretly professed Christianity. Upon learning of this, the emperor ordered to shoot him with a bow. However, Sebastian remained alive and began to expose the authorities for crimes against Christians. Then Diocletian gave a second order for execution. Sebastian was beaten with sticks, from which he died in 287. Thanks to the chronograph 354 years Chronograph is a monument of ancient writing containing a summary of world history. we also know that the saint is buried in the Roman catacombs.

Thanks to the chronograph 354 years Chronograph is a monument of ancient writing containing a summary of world history. we also know that the saint is buried in the Roman catacombs.

Mosaic in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Saint Sebastian. Detail of a mosaic depicting the procession of martyrs. Ravenna, middle of the 6th century ruicon.ru

The earliest image of Saint Sebastian that has come down to us is a mosaic from the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, created in the middle of the 6th century. You can recognize Sebastian only by the corresponding signature: he is only one of 26 participants in the procession of saints and martyrs who march to the throne of Jesus Christ from Theodoric’s palace Theodoric The Great (454-526) – king of the Ostrogoths, who by 493 conquered most of Italy and founded a kingdom there with its capital in Ravenna. Theodoric was a Christian, but he professed Arianism, that is, he believed that God the Son was created by God the Father. Theodoric himself was probably depicted at the head of the procession, but by the end of the century, when Ravenna was under the influence of Byzantium, the Arian mosaics were replaced with new ones, and on Theodoric is no longer there. The saints almost do not differ from each other: all, except Saint Martin and Saint Lawrence, are dressed in white togas of Roman patricians and carry crowns of thorns in their hands – a symbol of martyrdom. Sebastian is depicted as an elderly bearded man: age is the only historical detail in his appearance. nine0004

Theodoric himself was probably depicted at the head of the procession, but by the end of the century, when Ravenna was under the influence of Byzantium, the Arian mosaics were replaced with new ones, and on Theodoric is no longer there. The saints almost do not differ from each other: all, except Saint Martin and Saint Lawrence, are dressed in white togas of Roman patricians and carry crowns of thorns in their hands – a symbol of martyrdom. Sebastian is depicted as an elderly bearded man: age is the only historical detail in his appearance. nine0004

Andrea Mantegna. “Saint Sebastian” (

1457–1459 )

Kunsthistorisches Museum / Google Art Project

In the painting by Andrea Mantegna, the body of the saint is tense, and he is tied not to a tree, but to a column of a triumphal arch, resembling a marble statue rather than a person. The background of the painting is symbolic: the pagan world is a thing of the past, the arch is destroyed, fragments of ancient statues are scattered at the saint’s feet. The sandaled foot and head may have belonged to one of the 200 stone idols that Sebastian destroyed, according to The Golden Legend. A little further on lies another fragment – a piece of relief with cupids picking grapes from an ancient sarcophagus: grape picking could symbolize the sacrifice of Jesus and the Eucharist. nine0004

The sandaled foot and head may have belonged to one of the 200 stone idols that Sebastian destroyed, according to The Golden Legend. A little further on lies another fragment – a piece of relief with cupids picking grapes from an ancient sarcophagus: grape picking could symbolize the sacrifice of Jesus and the Eucharist. nine0004

In the cloud in the upper part of the picture, on the left, the figure of a rider is visible. Perhaps Mantegna again recalls the Golden Legend, where a version is given according to which the name Sebastian comes from the word basto – “saddle”, which means that the saint is the saddle of Jesus, where the church is the horse, and Jesus himself is the rider.

Antonello da Messina. “Saint Sebastian” (

c. 1478)

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The image of Saint Sebastian becomes truly popular in Italy in the 15th century. Renaissance paintings depict the first execution: Sebastian is tied to a tree, and arrows pierce his body. Now the saint looks young and has no beard. The number of arrows also decreases, although Jacob Voraginsky wrote that during the first execution the saint resembled a hedgehog – so many arrows were fired at him. But Renaissance artists focus on the beauty of Sebastian’s body, not the number of wounds—pain rarely distorts the saint’s face. nine0004

Now the saint looks young and has no beard. The number of arrows also decreases, although Jacob Voraginsky wrote that during the first execution the saint resembled a hedgehog – so many arrows were fired at him. But Renaissance artists focus on the beauty of Sebastian’s body, not the number of wounds—pain rarely distorts the saint’s face. nine0004

The tree to which the saint is tied grows by the canal in one of the Venetian squares. The execution scene does not disturb the idle calm of the city, its inhabitants continue to walk, and the guard – the only character associated with Sebastian – fell asleep. The balconies of the palace are decorated with Turkish carpets: they remind of the prosperity of Venice, which happened thanks to trade with the Ottoman Empire.

The veneration of St. Sebastian increased in the 14th and 15th centuries, along with the black death that came in the middle of the 14th century: it was believed that Sebastian helped protect against the plague. With the arrival of the plague in Venice in 1477, the picture of da Messina is also associated. However, the artist died just a year later in his native Sicily, so it is not known whether he could have received and completed such an order. nine0004

However, the artist died just a year later in his native Sicily, so it is not known whether he could have received and completed such an order. nine0004

Jos Liferinks. The Intercession of Saint Sebastian (

1497–1499 )

The Walters Art Museum

sent from Rome to Pavia, which was stricken with an epidemic. The relic was placed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, an altar was dedicated to Sebastian, after which the plague left.

Sebastian’s relics ended up in Pavia for political rather than religious reasons. At that time, the cult of Sebastian as a protector from the plague did not yet exist, but he was considered, along with Peter and Paul, the patron saint of Rome. Shortly before the start of the epidemic, the then Pope Agathon made an alliance with the Lombards Kingdom of the Lombards (568-774) – a state in northern Italy, created by the Germanic tribe of the same name. In the 7th century, most of modern Italy was under the rule of the Lombards. The transfer of the relics of one of the most influential Roman saints to Pavia strengthened this union, and the subsequent healing of the city testified that the union was approved by Heaven.

The transfer of the relics of one of the most influential Roman saints to Pavia strengthened this union, and the subsequent healing of the city testified that the union was approved by Heaven.

In the 1460s, after an absence of almost a century, the plague returned to the south of France, outbreaks in various cities continued until the beginning of the 16th century. The plague came to Marseille in 1476, 1483–1485, 1490 and 1494. Three years after another epidemic, in 1497, the Avignon artist Jos Lieferinx painted the story of the life of Saint Sebastian for the altar of the Notre-Dame-des-Accules church in Marseille. The altar is also dedicated to two other protectors from diseases – St. Roch and St. Anthony. One of the scenes depicts the intercession of Saint Sebastian. Lieferinx relies on a story from the Golden Legend, which is based on a plot from the History of the Lombards, written at the end of the 8th century by the medieval monk Paul the Deacon. The painting depicts Pavia, where the disease is rampant: the living do not have time to bury the dead, and right at the time of the funeral, the plague strikes one of the gravediggers. Two angels are visible in the sky: according to the Golden Legend, many saw how an angel in white robes showed the angel of death which house to hit with a spear, after which the dead were carried out from there. In the distance, on a cloud, Saint Sebastian prays to God to save the city. However, the artist has never been to Pavia, so the painting most likely depicts his native Avignon. nine0004

Two angels are visible in the sky: according to the Golden Legend, many saw how an angel in white robes showed the angel of death which house to hit with a spear, after which the dead were carried out from there. In the distance, on a cloud, Saint Sebastian prays to God to save the city. However, the artist has never been to Pavia, so the painting most likely depicts his native Avignon. nine0004

Jusepe Ribera. “Saint Sebastian and Saint Irina” (

1628 )

State Hermitage Museum

After Diocletian ordered the archers to shoot Sebastian, the saint was left tied to a tree to die. At night, Saint Irina came to the place of execution. She pulled the arrows out of Sebastian’s body, took him to her home and cured him. This story appears in the middle of the 17th century in the collection Acts of the Saints, compiled by the Jesuit Jean Bolland. It is based on earlier medieval texts. In art, the line about St. Irene appears even earlier – in the 15th century. nine0004

nine0004

Sebastian’s healing from wounds and his ability to stop the plague were considered a miracle: the plague would bypass the one who prayed, just as Sebastian’s arrows passed by the executioners. At the end of the 16th – 17th centuries, during the era of the Counter-Reformation, Saint Irene appears more and more often in the images of the execution of the saint – and the church strongly supports this plot, trying to restore the trust of Catholics. The image of Irina showed Christians, and especially Christians, an example of compassion and concern for others, and also rationally explained how Sebastian survived. This scene was often referred to by artists influenced by Caravaggio, including Jusepe Ribera. He spent most of his life in Naples, where he saw the works of Caravaggio. nine0004

Only one arrow remains in the saint’s body in this painting. The viewer’s attention is riveted to Sebastian, while the women’s faces remain in twilight. Unlike most artists who portrayed Irina and her assistant freeing Sebastian from the ropes, Ribera leaves the saint tied to a tree. The thrown back head, bare neck, and outstretched hand emphasize his defenselessness.

The thrown back head, bare neck, and outstretched hand emphasize his defenselessness.

Lodovico Carracci. “Saint Sebastian is thrown into the cesspool of Maximus” (1612)

The J. Paul Getty Trust

After Saint Irene saved Sebastian, he came to Diocletian’s palace and began to reproach him for his cruelty towards Christians. The enraged emperor ordered the saint to be executed again, namely, to beat him with sticks, and then dump the body into the cesspool of Maximus Cloaca Maxima, or the Great Cloaca, (from Latin Cloaca Maxima) – part of the ancient sewage system in Ancient Rome. – still existing channel of the sewer system, laid down in the VI century BC. e.

On the night after his death, Sebastian appeared to the pious Roman matron Lucina, showed her where his body was dumped, and the woman buried him in the catacombs near the Appian Way Appian Way is one of the most important public roads in Rome, built in the 4th century BC. e. Many Christian saints and martyrs were buried in the catacombs on the Appian Way. . A small church was built near the spot where Lucina discovered the saint’s body, but in the 17th century it had to be demolished to make way for the Basilica of Sant’Andrea della Valle. To preserve the memory of what happened here, one of the chapels of the new basilica was dedicated to Saint Sebastian, and the Barberini family chapel was painted with scenes from his life. nine0004

e. Many Christian saints and martyrs were buried in the catacombs on the Appian Way. . A small church was built near the spot where Lucina discovered the saint’s body, but in the 17th century it had to be demolished to make way for the Basilica of Sant’Andrea della Valle. To preserve the memory of what happened here, one of the chapels of the new basilica was dedicated to Saint Sebastian, and the Barberini family chapel was painted with scenes from his life. nine0004

Egon Schiele. Self-portrait as Saint Sebastian (

1914–1915 )

Wikimedia Commons

In 1915, a personal exhibition of Egon Schiele opened at the Arno Gallery in Vienna. For the poster, Schiele used a self-portrait as Saint Sebastian. In many of his portraits, the artist portrayed himself looking at the viewer point-blank. Here, his eyes were closed, and his body hung limply in the air, meeting a hail of arrows.

Pierre and Gilles. “Saint Sebastian” (

1987 )

© Pierre et Gilles / burnley college digital photography / Flickr. com

com

Beginning in the 15th century, artists who turned to the image of St. Sebastian increasingly focused on the beauty of his naked body, while martyrdom faded into the background. Back in the first half of the 16th century, Giorgio Vasari told in his book “Lives of the Most Famous Painters, Sculptors and Architects” that in the monastery of San Marco in Florence they decided to remove the image of St. Sebastian from the church: many parishioners confessed in confession that the picture they have sinful thoughts. Finally, by the 20th century, the image of this handsome young man became part of gay culture. In the brilliant, kitsch photographs of Pierre and Gilles, Saint Sebastian looks too desirable: without hiding their irony, the artists exaggerate the meanings that the images of Saint Sebastian endowed their predecessors with. nine0004

Sources

- Voraginsky I. Golden legend. Apostles

M., 2016.

- Kon I. The male body in the history of culture.

M., 2003.

- Lazarev V. N. The history of Byzantine painting.

M., 1986.

- Lazarev V. N. Old Italian masters.

M., 1972.

- Brown L. B. As Time Goes By: Temporal Plurality and the Antique in Andrea Mantegna’s “Saint Sebastian” and Giovanni Bellini’s “Blood of the Redeemer”. nine0003 Artibus et Historiae. Vol. 34. Vienna, Cracow, 2013.

- Katz M. Preventive Medicine: Josse Lieferinxe’s Retabel Altar of Saint Sebastian as a Defense against Plague in 15th-century Provence.

Interfaces journal. No. 26. Worcester, 2006.

- Piety and Plague: From Byzantium to the Baroque.

Ed. Franco Mormando, Thomas Worcester. Kirksville, 2007.

- The Age of Caravaggio.

Ex. Cat. New York, 1985.

Tags

Painting

Middle Ages

Antiquity

Scit pad

Microstrues

Daily short materials that we have produced for the past three years

French-Russian souvenir

9000 Ethnonym of the day

Belarusian, Belarusian

Archive

Literature

From and to: put the events of The Lord of the Rings in the correct order

.

How Saint Sebastian became the patron saint of gay people

How Saint Sebastian became the patron saint of gay people.

Of course, today there is no clear indication or proof that Saint Sebastian was gay during his lifetime. But over time, the image of this saint acquired an extremely strange appearance. The combination of his physique, partial or complete nudity, the symbolism of arrows penetrating his flesh, and the hidden pain that Sebastian experienced, led to the fact that artists over the centuries painted pictures of the martyr saint, and in the nineteenth century did it altogether. “icon of homosexuality”. But why did gays begin to consider the saint as their patron? nine0225

Saint Sebastian has been known for centuries as a symbol of devotion to Christian ideals, and more recently he is considered the patron saint of gays. And even though the Vatican has been arguing since time immemorial about what to do with sexual diversity – accept it, tolerate it as a necessary evil, or hunt it again, the presence of such an icon, which mixes mysticism, religiosity and strangeness , clearly runs counter to the religious system and its morality. nine0004

nine0004

Saint Sebastian. Giovanni Antonio de Bazzi. 1525–26

Saint Sebastian was one of the adherents of the teachings of Christ, for which he was killed in 288 by order of the Roman emperor Diocletian. As a Roman soldier, he secretly practiced Christianity despite the official ban. When Sebastian was arrested and interrogated, he refused to renounce Christianity. After that, Diocletian gave the order to take the rebellious soldier outside the city and shoot him with bows. Despite this, Sebastian managed to survive, and a certain Irina came out of him (who later was also canonized). When Sebastian recovered, the Christians persuaded him to flee, but the fanatical soldier again went to the emperor with supposed proof of his faith. Diocletian had him stoned and clubbed to death. nine0004

Martyrdom of St. Sebastian.

The peak of the popularity of the image of St. Sebastian came in the 16th century. At this time, more and more artists began to create paintings of the execution of the saint. In classical iconography, Sebastian was represented as a handsome young man, usually half-naked and pierced with arrows, and his face expressed either pain or ecstasy. It was this image that began to be considered a reference to the LGBT community.

In classical iconography, Sebastian was represented as a handsome young man, usually half-naked and pierced with arrows, and his face expressed either pain or ecstasy. It was this image that began to be considered a reference to the LGBT community.

The martyrdom of Sebastian, a legionary turned saint. Probably a painting by Michelangelo. nine0004

One of the most remarkable paintings with this character was created by El Greco. The brilliant artist managed to combine images of darkness, sensuality and desire in a seemingly tragic picture. A great example of the expressiveness and objectivity inherent in the artist’s latest work, this painting is also a wonderful example of how a saint can be portrayed in such a way that he becomes an icon for people with whom it was previously very difficult to associate him.

Saint Sebastian. El Greco. nine0004

The same applies to the painting by Guido Reni, which subsequently inspired Oscar Wilde and Yukio Mishima to hypersensitivity in their works. And how can we forget Andrea Mantegna, the Renaissance artist who made Saint Sebastian the central theme of three of his works.

And how can we forget Andrea Mantegna, the Renaissance artist who made Saint Sebastian the central theme of three of his works.

It was these legendary artists who made the saint look like a young man who, in addition to pain, simply “radiates” eroticism with his body curves, skin color, loose hair and strong muscles. nine0004

One of the most erotic images.

Despite all the pain he must be experiencing, the saint’s face is usually depicted as calm or, moreover, expressive of ecstasy. From the point of view of the church, this should symbolize ecstasy or the highest degree of joy before the fact that Sebastian is about to meet God. However, the seductive features of the saint took on another interpretation, becoming “sacred” for gays.

Saint. Angel Sarraga.

The Church attempted to combat this custom by introducing edicts that prevented the circulation of overly sensual works and by punishing any believer who “saw the other side of the saint.

Chaeromon: Saint of the Day for Thursday, December 22, 2022

Chaeromon: Saint of the Day for Thursday, December 22, 2022