Spanish soldier 1500: The Spanish — myArmoury.com

The Conquistador Story | Texas State History Museum

Skip to main menuSkip to page contentSkip to footer

Search

- High Contrast

- Museum Store

- Calendar

- Buy Tickets

Searching for gold and glory and finding something else

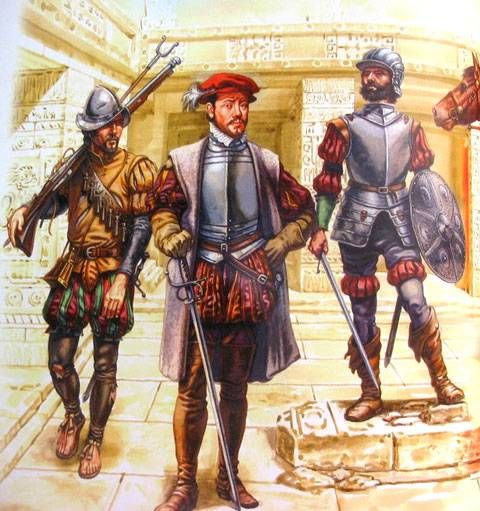

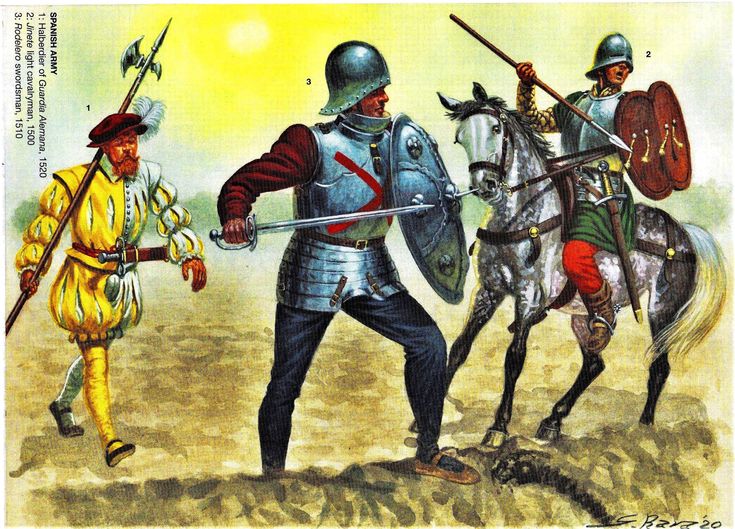

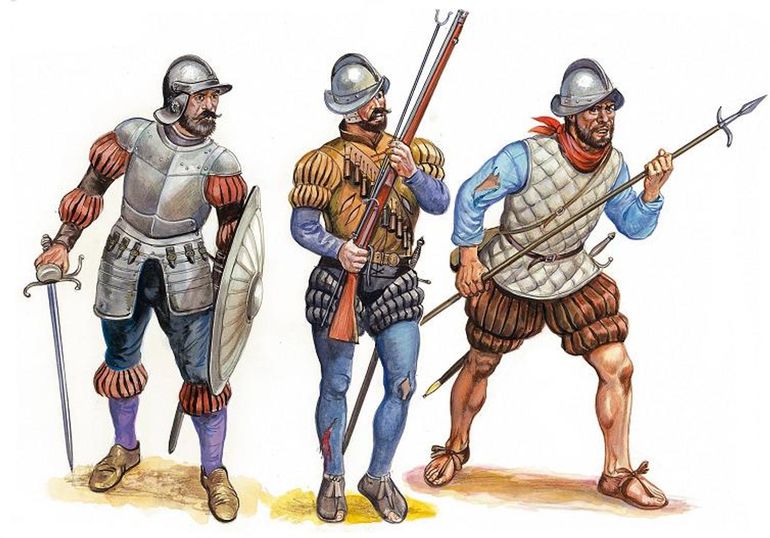

Soon after Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas in 1492, the Spanish began to hear stories of civilizations with immense riches. Hoping to claim this wealth and territory for Spain and themselves, conquistadors, or “conquerors,” sailed across the Atlantic Ocean.

When they ventured onto the mainland, they found an immense landscape that was already home to tens of thousands of American Indians. Conflict between the two groups was frequent, leading to misunderstandings, exploitation, and violence. While their explorations gave Europeans a better understanding of the Americas, the conquistadors who explored the land now known as Texas often failed to find the wealth and resources they were looking for leading the Spanish to focus colonization efforts further south for many years.

This clearly shows how the designs of men sometimes miscarry.

Cabeza de VacaShare

Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca

When Cabeza de Vaca joined fellow Spanish explorer Pánfilo de Narváez on an expedition to conquer and colonize the North American Gulf Coast in 1528, he began a journey that would take more than eight years to complete.

In 1519, the explorer Alonso Álvarez de Piñeda became the first European to map the Texas Gulf Coast. However, it would be another nine years before any Spaniards explored the Texas interior.

In 1528, another expedition, led by Pánfilo de Narváez, set sail from Spain to explore the North American interior. A long series of disasters left most of the expedition dead. A group of 90 men, headed by Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, shipwrecked near Galveston Island. The party included Estevanico, a North African enslaved man believed to be the first person of African descent to set foot in North America. Despite receiving food and shelter from the nearby Karankawa tribe, only fifteen of the men survived the winter.

Despite receiving food and shelter from the nearby Karankawa tribe, only fifteen of the men survived the winter.

For the next eight years, Cabeza de Vaca and the remaining survivors would become the first Europeans to view the diversity of the landscape and people of what we now call Texas. Moving between the mainland and the coast, Cabeza de Vaca worked as a trader and healer to survive, with the ultimate goal to make it to Mexico City.

On his journey south, Cabeza de Vaca rediscovered three Spaniards who had been separated from his party soon after their shipwreck. These men had been enslaved by an American Indian group known as the Mariames. Once reunited, Cabeza de Vaca was also enslaved.

Six years after the expedition began, the four men escaped the Mariames one by one and headed south, where they were taken in by members of the Avavares tribe. After recuperating for eight months, the men set out for Mexico. They followed a winding route that covered approximately 2,400 miles, and took them south of the Rio Grande, across northern Mexico, and eventually south to Mexico City.

In the eight years they spent in Texas, Cabeza de Vaca and his companions failed to discover any gold or claim any new territory for Spain. Instead, they returned with tales they heard from American Indians of riches elsewhere in North America. Rumors like these fueled Spanish exploration of Texas and the surrounding areas for nearly 70 years.

Share

Cabeza de Vaca and his companions took an indirect route from Texas to Mexico City. Believing the coast was occupied by hostile tribes, they headed west along the Rio Grande instead. They stayed with American Indian tribes along the way, finally reaching Culiacan in January 1536. They arrived in Mexico City six months later. Image courtesy We Came Naked and Barefoot: The Journey of Cabeza de Vaca across North America by Alex D. Krieger, edited by Margery H. Krieger, University of Texas Press, © 2002

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado

Cabeza de Vaca’s tales of riches were reinforced when a Franciscan friar reported cities of gold in present-day New Mexico. In 1540, Viceroy Antonio Mendoza ordered Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to lead an expedition to the northern reaches of the Spanish empire to conquer the region and claim the wealth for Spain.

In 1540, Viceroy Antonio Mendoza ordered Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to lead an expedition to the northern reaches of the Spanish empire to conquer the region and claim the wealth for Spain.

Coronado gathered 1,000 men and thousands of horses, mules, sheep and cattle for the expedition. They marched north for two-and-a-half months before reaching the Zuñi pueblo of Hawikuh in present-day northwestern New Mexico.

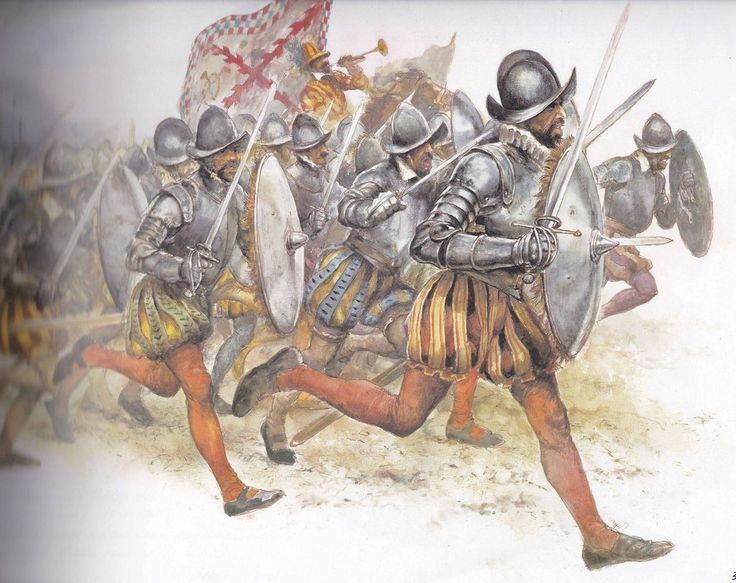

Instead of streets paved with gold, the party found a city of more than 500 families living in buildings constructed of sandstone and adobe. Coronado read the Zuñis the Requerimiento, a document in Spanish that ordered them to submit to the King of Spain’s rule and convert to Christianity; the Zuñis responded by firing arrows at the Spanish soldiers. Coronado attacked. Despite the Zuñis best efforts to defend their city, the Spanish soldiers stormed Hawikuh’s walls and captured or killed most of the Zuñis who could not escape.

Soon after he seized Hawikuh, Coronado heard rumors of another golden kingdom, Quivira, to the east. He headed in that direction, crossing the Texas Panhandle on his way to the Great Plains. He sighted Palo Duro Canyon during his expedition, but found no treasure. Coronado returned to Mexico City empty-handed in 1542. His failure to locate the Seven Cities of Cíbola, Quivira or any other riches discouraged further Spanish exploration in the region for many years to come.

He headed in that direction, crossing the Texas Panhandle on his way to the Great Plains. He sighted Palo Duro Canyon during his expedition, but found no treasure. Coronado returned to Mexico City empty-handed in 1542. His failure to locate the Seven Cities of Cíbola, Quivira or any other riches discouraged further Spanish exploration in the region for many years to come.

Coronado’s interactions with the Zuñis at Hawikuh were typical of how many conquistadors approached American Indians. The Spanish read them the Requerimiento in a foreign language and if the Native Americans resisted then the Spaniards took what they wanted by force. These tactics led to conflict, suffering, and often death for many American Indians throughout the Western Hempishere.

Share

American artist Kenneth Chapman depicted the battle between Spanish soldiers and Zuñis at Hawikuh in “Battle of Hawikuh, Coronado’s attack of July 6, 1540.” Chapman created this artwork in 1911. Battle of Hawikuh, Coronado’s attack of July 6, 1540, 1911. Image courtesy the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), 048918

Battle of Hawikuh, Coronado’s attack of July 6, 1540, 1911. Image courtesy the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), 048918

Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado

As Coronado was returning to Mexico, another Spanish expedition stumbled into present-day Texas.

Hernando De Soto and his men set out from Florida in search of large cities and abundant treasure, but the expedition found neither of these things. In the Spring of 1542, right in the midst of his explorations, De Soto fell ill and died, leaving Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado in charge of the expedition. After burying De Soto on the Mississippi River, Moscoso and his men abandoned the search for riches and decided to head west to Mexico. They marched into Ais and Caddo territory in present-day East Texas where the Spanish soldiers attacked Caddo towns and stole the American Indians’ food stores to feed themselves. One Caddo cacique, or chief, ordered his men to guide the Spaniards into another, less well-stocked band’s territory. When Moscoso discovered the trick, he had the guides hanged, and then turned back for the Mississippi River soon after.There they built several small boats, sailed down the Mississippi River, and followed the Gulf Coast to Mexico. Upon reaching Mexico in September 1542, Moscoso reported the expedition’s failure to locate any of the large, wealthy cities De Soto sought. His account, combined with Coronado’s failure to locate any of the supposed cities of gold, reinforced Spain’s decision not to further explore the northern frontier.

When Moscoso discovered the trick, he had the guides hanged, and then turned back for the Mississippi River soon after.There they built several small boats, sailed down the Mississippi River, and followed the Gulf Coast to Mexico. Upon reaching Mexico in September 1542, Moscoso reported the expedition’s failure to locate any of the large, wealthy cities De Soto sought. His account, combined with Coronado’s failure to locate any of the supposed cities of gold, reinforced Spain’s decision not to further explore the northern frontier.

Share

Even though he didn’t find any riches to speak of, Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado continued traveling in North America. He died in 1550 in Peru.

Antonio de Espejo

It was 40 years before explorers returned to the northern boundaries of Spain’s territories again. This time the Spanish weren’t searching for gold, but for missing men.

In November 1582, Antonio de Espejo set out from Nueva Vizcaya, Mexico, to search for some friars who had traveled to northern New Mexico to convert the American Indians there. Espejo learned early in his expedition that the two friars had been killed by members of the Tiguex tribe in present-day New Mexico. Nevertheless, he continued on and explored the areas to the north and east. He pushed north into Tiguex territory, then headed east until he reached the Pecos River. He and his men followed the Pecos south and crossed into present-day Texas, where they were welcomed by Jumano who acted as Espejo’s guides, leading him through the Trans-Pecos region and back to the Rio Grande.

Espejo learned early in his expedition that the two friars had been killed by members of the Tiguex tribe in present-day New Mexico. Nevertheless, he continued on and explored the areas to the north and east. He pushed north into Tiguex territory, then headed east until he reached the Pecos River. He and his men followed the Pecos south and crossed into present-day Texas, where they were welcomed by Jumano who acted as Espejo’s guides, leading him through the Trans-Pecos region and back to the Rio Grande.

One of the members of Espejo’s expedition, Diego Pérez de Luxán, kept a daily record of the journey. His detailed descriptions of the landscape and American Indians the Spaniards encountered encouraged further exploration and, eventually, settlement of present-day New Mexico. However, his descriptions of the Trans-Pecos region didn’t inspire the Spanish to explore what is now Texas further.

They [the Jumanos] cover themselves with well-tanned skins of the cibola [bison].

The hides they tan and beat with stones until they are soft. They fight with bows and arrows. … They cultivate corn, beans, and calabashes.

– Diego Perez de Luxán, official diarist of the Espejo expedition

Juan de Oñate

Juan de Oñate would be the last of the conquistadors to traverse present-day Texas. Unlike his predecessors, his explorations would have a direct and lasting impact on the region.

In early 1598, Juan de Oñate led an expedition to settle present-day New Mexico. Unlike some of his predecessors, who were only tasked with claiming land and finding resources, Oñate was ordered to establish a colony. Many of the colonists in his party hoped to find their own riches mining silver. On his way north he crossed the Rio Grande at El Paso del Norte, the site of the modern city of El Paso. It was there that he formally declared Spanish possession of what is now New Mexico. After establishing the colony’s new headquarters near modern-day Santa Fe, Oñate followed in Coronado’s footsteps and headed east in search of the city of gold, Quivira. Like Coronado before him, he failed to find any riches on the Great Plains.

Like Coronado before him, he failed to find any riches on the Great Plains.

During his brief time in the region, Oñate’s expedition found nothing the Spanish were searching for: no cities of gold, no precious metals, and no jewels. However, his actions would have great impact on Texas in the coming decades. His route through El Paso del Norte—a route already well-known to Native American populations who had used it for trade long before Spanish arrived—became El Camino Real del Norte. This road would serve as a crucial lifeline connecting New Mexico to the capital in Mexico City. Its location on El Camino Real del Norte made El Paso del Norte an important trading and transportation hub in the future.

Share

After traveling across the harsh Chihuahuan Desert, Juan de Oñate and his party followed the Rio Grande north in search of a pass through the mountains. When they reached one – El Paso del Norte – they celebrated by feasting with members of the Mansos tribe, who helped guide them. Twentieth-century El Paso artist José Cisneros recreated the celebratory scene in this illustration. Image courtesy UTEP Library Special Collections via Texas Beyond History

Twentieth-century El Paso artist José Cisneros recreated the celebratory scene in this illustration. Image courtesy UTEP Library Special Collections via Texas Beyond History

The Story Continues

The conquistadors collected, recorded, and published a wealth of knowledge about the land we call Texas, but knowledge was not the primary goal of the Spanish crown. Spain wanted riches to fund their political goals in Europe, and the conquistadors found none in Texas. After decades of exploration that frequently led to conflict and violence with local American Indians, the region was largely ignored for another 100 years until the late 1600s when another European presence would seek to insert itself into the complex network of people already living in Texas.

Launch Master Timeline

Conquistadors Timeline

1492

1492Spain Takes Notice

On August 3, 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed west from Palos, Spain, to explore a new route to Asia. On October 12, he reached the Bahamas. Six months later, he returned to Spain with gold, cotton, American Indian handicrafts, exotic parrots, and other strange beasts. His tales of the native peoples, land, and resources in North America ignited the era of Spanish colonization.

On October 12, he reached the Bahamas. Six months later, he returned to Spain with gold, cotton, American Indian handicrafts, exotic parrots, and other strange beasts. His tales of the native peoples, land, and resources in North America ignited the era of Spanish colonization.

1519

1519Into the Gulf of Mexico

Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda is credited with being the first European to explore and map the Gulf of Mexico. He set out with four ships and 270 men to find a passage to the Pacific Ocean. There are few records detailing his exploration, although one Spanish document does indicate that he sailed around the coast of Florida, into the Gulf of Mexico, and up a river dotted with palm trees and the villages of native peoples. Earlier interpretations of his voyage identified this river as the Rio Grande, but later data shows that it was probably the Soto la Marina, located in Mexico.

1527

1527Failure Sets the Stage

In 1527, with five ships, 600 men, and a supply of horses, Pánfilo de Narváez set out for Florida to claim gold and glory for the Spanish empire. His trip seemed doomed from the beginning. Many of his men died, deserted, or were killed by the American Indians whose people and villages the expedition attacked and pillaged. In an effort to escape, Narváez and the remaining members of the expedition set sail in flimsy rafts that were eventually washed up on the Texas Gulf Coast near Galveston. Narvárez drowned on the voyage, but one of the few survivors, conquistador Cabeza de Vaca, wrote detailed memoirs that became the earliest European descriptions of Texas and its people.

His trip seemed doomed from the beginning. Many of his men died, deserted, or were killed by the American Indians whose people and villages the expedition attacked and pillaged. In an effort to escape, Narváez and the remaining members of the expedition set sail in flimsy rafts that were eventually washed up on the Texas Gulf Coast near Galveston. Narvárez drowned on the voyage, but one of the few survivors, conquistador Cabeza de Vaca, wrote detailed memoirs that became the earliest European descriptions of Texas and its people.

1528

1528A Desperate Account

Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, one of four survivors of the failed Narváez expedition, washed up on the beach of a Texas Gulf Coast island he named “Malhado,” which means “misfortune.” The name was apt, because for the next several years, Cabeza de Vaca lived one harrowing moment to another as a captive slave of various Texas American Indians. He kept a detailed diary which has become an invaluable primary source describing the life and peoples of early Texas. In 1536, Spanish soldiers returned Cabeza de Vaca to Mexico City. He eventually made his way back to Spain where he published his memoirs, The Narrative of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, in 1542.

In 1536, Spanish soldiers returned Cabeza de Vaca to Mexico City. He eventually made his way back to Spain where he published his memoirs, The Narrative of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, in 1542.

1536

1536A Voice for Human Rights

Bartolomé de las Casas was the first priest to be ordained in the Americas. Conscience-stricken by the abuse of American Indians at the hands of Spanish conquistadors, he crusaded on the native peoples’ behalf for over five decades. In 1536, de las Casas participated in a debate in Oaxaca, Mexico, where he argued for the American Indians’ right to be treated as individuals with dignity and against the Spanish efforts to convert native peoples to both the Catholic faith and the Spanish culture. His blistering work in 1542, A Brief Report on the Destruction of the Indians, convinced King Charles V to outlaw the conversion practices, but riots among land holders in New Spain (Mexico) convinced authorities not to make any changes in their treatment of American Indians.

1541

1541Unexpected Discoveries

Finding gold was one objective of Spanish colonization in North America. Following the report of an explorer who claimed to have seen a gold city in the desert, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado organized an expedition that traveled through the Texas Panhandle. Various historical accounts describe the soldiers’ astonishment at the Texas landscape, including Palo Duro Canyon, and the huge, hump-backed cows (buffalo) that roamed the grasslands. Coronado never found any gold in the Panhandle, and the expedition returned to Mexico in 1542.

1542

1542Moscoso Enters East Texas

Hernando de Soto led an exploration of the Gulf Coast area from 1539 until his death in present-day Arkansas in 1542. This expedition marked the first European crossing of the Mississippi River. After de Soto’s death, Luis de Moscoso led the explorers into East Texas, home of the powerful Caddo Indians, in an attempt to find an overland route back to New Spain (Mexico). Opinions differ as to the exact route the Moscoso expedition took through Texas, but recent scholarship suggests that they traveled south from East Texas toward present-day Nacogdoches and then into the Hill Country before turning back toward the Mississippi River in Arkansas.

Opinions differ as to the exact route the Moscoso expedition took through Texas, but recent scholarship suggests that they traveled south from East Texas toward present-day Nacogdoches and then into the Hill Country before turning back toward the Mississippi River in Arkansas.

1554

1554Bad Weather and Bad Luck

In November, 1552, fifty-four vessels sailed from Spain under the command of Captain-General Bartolomé Carreño. The ships, including six armed vessels, carried cargo and were headed to various parts of the world including New Spain (Mexico) and the Indies. On April 29, 1554, three ships were wrecked in a storm on Padre Island, near present-day Port Mansfield. In the 1960s and 1970s, excavation efforts retrieved thousands of artifacts such as cannons, silver coins, gold bullion, astrolabes, and tools from the wreckage of the San Esteban and the Espiritu Santo. The third sunken ship, the Santa Maria de Yclar, was destroyed during ship channel construction in the 1950s.

1581

1581Church and State

The Spanish missionary system was intended to convert American Indians to Christianity and teach them how to live according to Spanish ways. Missionaries often accompanied conquistadors on their explorations in North America. The first missionaries passed through far west Texas in 1581 on their way to the pueblos of New Mexico.

1582

1582Jumano of Big Bend

Though unsuccessful in establishing a colony among the Pueblo people, Spanish conquistador Antonio de Espejo left a valuable account of his encounters with the Jumano people of Texas’s Big Bend area in 1582 to 1583. The Jumano were trading partners of the Spanish for almost two centuries before famine and war sent their population into a steep decline.

1598

1598Claiming All the Land

After a difficult march through present-day New Mexico and Texas, conquistador Juan de Oñate and hundreds of settlers finally reached the Rio Grande in April. They were so grateful to have survived the journey that they held what some believe was the first “thanksgiving” feast in what would become the United States. During this stop, Oñate officially claimed all the land drained by the Rio Grande as Spanish territory. With this act, the foundation was laid for two centuries of Spanish control of Texas and the American southwest.

They were so grateful to have survived the journey that they held what some believe was the first “thanksgiving” feast in what would become the United States. During this stop, Oñate officially claimed all the land drained by the Rio Grande as Spanish territory. With this act, the foundation was laid for two centuries of Spanish control of Texas and the American southwest.

Back to full view

Make your mark on Texas History

Share Your Story

- What artifact do you have related to the Spanish exploration of Texas?

- What personal story can you tell related to the Spanish exploration of Texas?

- How do the Spanish conquistadors help tell Texas’s story?

- What other story related to this topic would you like to share?

Read Stories

From People Across Texas

Browse All Stories

Conquistadors

16th CenturyAfrican Americans

1821-1865American Indians

BCE- 1600Buffalo Soldiers

1850-1880Cattle Ranchers

1850-1880sFrontier Folk

1820-1850Missionaries

1500-1750Roughnecks

1890-1950Texas Rangers

1821-PresentVaqueros

1519-presentWomen Airforce Service Pilots (WASP)

World War II

The Great Spanish Conquistadors

By Gary W.

Gallagher, PhD, University of Virginia; Patrick N. Allitt, PhD, Emory University; Allen C. Guelzo, PhD, Gettysburg University

Gallagher, PhD, University of Virginia; Patrick N. Allitt, PhD, Emory University; Allen C. Guelzo, PhD, Gettysburg University

As the king of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles of Habsburg controlled more territory than any European ruler since Charlemagne, yet he had fewer tools to enforce his control than any previous ruler. Charles harnessed his passion for imposing order and applied it to the administration of Spain’s new domains in America, where the great Spanish conquistadors ran amok looting Indian empires.

The Spanish discovering Colorado in 1540. (Image: By Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau Nieto/Public domain)

Charles was largely fine with the looting. However, when “low-lifers” such as Cortés and Pizarro began setting themselves up as self-appointed aristocrats, the Spanish crown shouldered its way into American affairs and set about instituting formal governments that would be subservient to the crown. The age of the great Spanish conquistadors would soon come to an end.

The Viceroyalty System

The highest level of Spanish government in America divided the conquests of the conquistadors into two enormous viceroyalties: the viceroyalty of New Spain, which included all of Mexico, Central America, and the West Indian islands—and the viceroyalty of Peru, which governed the Spanish conquests in South America. Each of these vice royalties was presided over by a viceroy appointed directly by the king.

The viceroyalties were expected to be governed in America in precisely the same way as the king governed in Spain, from the top downward. They had exactly one mandate, and that was to impose order, which they did with remarkable success, considering that only 250,000 Spaniards could be persuaded to emigrate to New Spain and Peru in the 1500s to back up the viceroys. From only a dozen outposts in 1530, the viceroys chartered 121 towns by 1574, and another 210 over the next 250 years.

This is a transcript from the video series The History of the United States, 2nd Edition.

Watch it now, Wondrium.

More importantly, between 1500 and 1650, the viceroys ensured that as much as 200 tons of gold and 16,000 tons of silver were extracted from mines in America, probably worth a total of about one and a quarter billion dollars. To put it another way, the American mines that the Spaniards were emptying of gold and silver provided three to five times the entire stock of gold and silver in European hands in that age.

Confronting the American Natives

To accomplish these goals required turning away from the conquistadors’ penchant for killing the Indian populations, and instead compelling the natives to being compliant and willing slaves who would keep the flow of gold and silver to Spain uninterrupted. Great estates, haciendas, were carved out of the former Indian empires. The owners of these estates were granted an encomendero. This was a right to levy forced service on neighboring Indian villages and Indian families.

Working from the other end, the church labored to Christianize the Indians, which meant, in the process, destroying traditional books, ending traditional religious practices among the Indians, and squeezing the Indians into the mold of Spanish culture. It was a process that had more or less three stages.

It was a process that had more or less three stages.

- The first process was enslavement, either literal enslavement, as the conquistadors did, or indirect enslavement by the encomendero.

- The second phase would be dislocation, as traditional Indian culture was suppressed or dispossessed and Spanish culture substituted, more or less, in its place.

- This would be followed by a third stage of confrontation as the Indians struggled to fight back, to resist their Spanish overlords, not only literally in resisting the levy of slave labor—of forced service, by the encomendero—but also the imposition of European culture and religion.

The Europeans, however, had one great ally that the Indians could not resist. That great unseen ally was disease.

Learn more about the new world where European ideas of society no longer applied

Diseases from Europe

One reason that disease turned out to be such a lethal ally of the Europeans was that nothing in the medical experience of the North American Indian tribes had prepared them for European diseases like smallpox, measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, whooping cough, dysentery, cholera, and even the self-inflicted disease of alcoholism.

European diseases like smallpox were lethal to North American Indian tribes. (Image: By en:Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590)/Public domain)

American Indian tribes had composed their civilizations and constructed their societies without being exposed to these European pathogens. This meant that even when the Europeans—like members of the church, friars, missionaries, priests, and the like—tried to treat Indians fairly, as they did, they could not control the communication of those diseases. European systems had spent centuries building up immunities against them, but Indian systems had no defenses against them.

Along the eastern shore of North America alone, there were probably as many as 17 major European epidemics among the Indian tribes, some of which traveled north from Mexico, others of which were passed on by incidental contact along the shorelines with passing European vessels. These epidemics included such devastating scourges as smallpox in 1519, typhus in 1531, and typhus again in 1585. That’s only pointing to the largest and most disastrous of them.

That’s only pointing to the largest and most disastrous of them.

The casualty list from these epidemics among Indians was horrendous. Estimates of deaths from these epidemics range anywhere from 70 to 9% of the eastern North American Indian population; that’s only speaking about eastern North America. The same percentage had probably prevailed at other points in America as well.

Learn more about how the Spanish tapped sources of wealth in the Americas

The Last of the Conquistadors

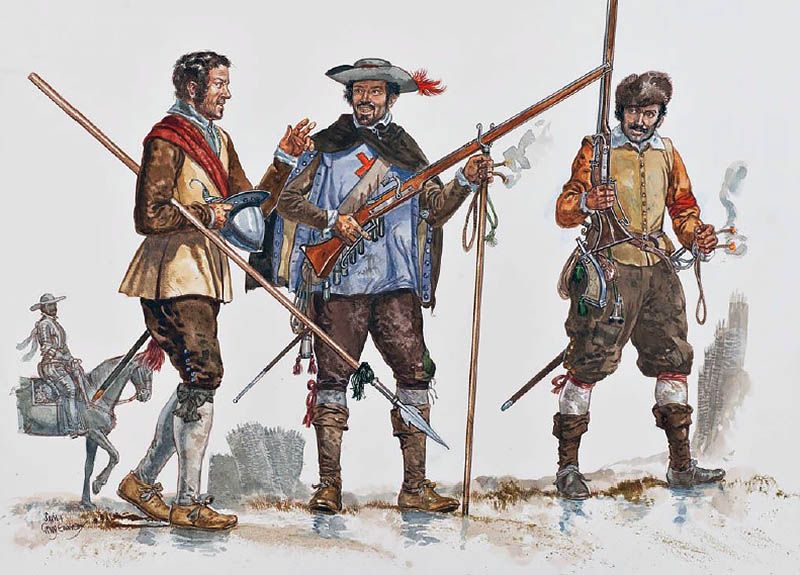

By the end of the 1600s, the Spanish New World settlements—ruled from a distance in Europe by King Charles V—had matured from being an extraction society, where people, like Cortés, came only in the hope of seizing wealth that they could take back and live upon in Spain. It had changed to a permanent settler society, where Spaniards became permanent colonists without any expectation of returning to Spain, wealthy or otherwise. Only a few were still trying to do the work—in this case, the profitable havoc of the conquistadors.

In 1516, Juan Ponce de Leon explored and mapped the coast of Florida. In 1521, he tried to do what his comrades had done, and that was to establish a profitable Spanish settlement there; the Indians killed him and drove the Spaniards off.

In 1539, one of Pizarro’s lieutenants from the conquest of Peru, Hernando de Soto, set off in pursuit of a Peru of his own to pillage. Using the wealth he had won at Pizarro’s side in Peru, de Soto financed another expedition to Florida, this time landing near modern-day Tampa, striking northwards into Georgia, and finally, turning westwards toward the Mississippi River. De Soto was probably the first European to encounter the Cherokee Indians of the Georgia uplands. What he found among the Cherokee ought to have surprised him: Roads, towns, farms, and temples.

De Soto seeing the Mississippi River for the first time. (Image: By William Henry Powell – Architect of the Capitol/Public domain)

De Soto was not interested in any of those things. What he wanted was gold. He and his men plunged blindly onward, crossing the Mississippi River, blundering through the Ozarks, until de Soto died of a fever and was buried in the waters of the Mississippi in May of 1542. De Soto found no gold. His only accomplishment, apart from being the first European to cross the Mississippi River, was to scatter European diseases among the Cherokee and the other tribes they passed through.

What he wanted was gold. He and his men plunged blindly onward, crossing the Mississippi River, blundering through the Ozarks, until de Soto died of a fever and was buried in the waters of the Mississippi in May of 1542. De Soto found no gold. His only accomplishment, apart from being the first European to cross the Mississippi River, was to scatter European diseases among the Cherokee and the other tribes they passed through.

The last of the great conquistador expeditions were mounted by Francisco de Coronado in 1540. He was pursuing rumors of gold among Indian cities on the Great Plains. He returned to Mexico empty-handed and financially ruined in 1542, having wandered with his 300 Spanish mercenaries, with no purpose, as far north as modern-day Kansas.

Learn more about the forced recruitment of a workforce of African slaves

The End of the Line

Surely, though, the strangest of this last round of conquistador expeditions was that of Panfilo de Narvaez, a former rival of Cortés who launched his own clumsy expedition into central Florida in 1528. Indians, disease, shipwreck, and starvation annihilated all but four of Narvaez’s expedition, including the expedition’s treasurer, Cabeza de Vaca. De Vaca was captured and enslaved by the Indians, along with a black mercenary named Esteban. In slavery, they palmed themselves off as medicine men and amazed the Indian tribes in Florida with an unexpectedly high success rate as healers. De Vaca and Esteban went almost overnight from being slaves to being celebrities. They were passed from tribe to tribe to perform healings, which somehow they managed to do.

Indians, disease, shipwreck, and starvation annihilated all but four of Narvaez’s expedition, including the expedition’s treasurer, Cabeza de Vaca. De Vaca was captured and enslaved by the Indians, along with a black mercenary named Esteban. In slavery, they palmed themselves off as medicine men and amazed the Indian tribes in Florida with an unexpectedly high success rate as healers. De Vaca and Esteban went almost overnight from being slaves to being celebrities. They were passed from tribe to tribe to perform healings, which somehow they managed to do.

Eventually, they were joined by two other survivors of the Narvaez expedition. Over eight years, they wandered from place to place, westward, until in 1536, in Western Mexico, they stumbled into a patrol of Spanish soldiers who looked at them in stark amazement. They had traveled over 1,300 miles through the American Southwest, thus making them, unwillingly, the most well-traveled Spaniards in the Western Hemisphere.

Learn more about how Dutch settlements developed into a major commercial center

This was a long way to fall from the heady days of Cortés and Pizarro, though. Being a conquistador was no longer turning the profits that it once had; the truth was that, as economic conditions in Europe shifted in the 16th century, Spain could no longer afford the freebooters, the adventurers, and the conquistadors.

Being a conquistador was no longer turning the profits that it once had; the truth was that, as economic conditions in Europe shifted in the 16th century, Spain could no longer afford the freebooters, the adventurers, and the conquistadors.

Common Questions About Spanish Conquistadors

Q: What exactly were the Spanish conquistadors after?

The Spanish conquistadors were essentially sanctioned pirates. Their goal was to claim land and resources for their investors and conquer natives of other lands for treasure and glory. They also were vital in the spread and enforcement of religion.

Q: Who is the most famous of the Spanish conquistadors?

The two most famous Spanish conquistadors were Francisco Pizarro, who conquered the Incan Empire, and Hernán Cortés, who took the Aztec Empire.

Q: Were all the conquistadors Spanish?

Conquistadors came from all over Europe, but most were Spanish conquistadors from southwestern Spain.

Q: What were the two primary intentions of the Spanish conquistadors?

The Spanish Conquistadors had many goals, but the two primary reasons for conquering were to steal wealth for their country and to civilize the natives with religion—in particular, Catholicism.

This article was updated on November 23, 2020

Keep Reading

The Dutch in America

American History: The Very First American Colonies

A Colony in Disarray: The Second Generation of Puritans

Other tables: | Whole world | | |

Dates | Return: Spain in the 15th century |

| 1500 | 1500: Portuguese sailor Pedro Alvares Cabral opens Brazil.  * * |

| 1502 | 1502: Muslims of Castile and Aragon forced to accept Christianity or leave the kingdom. Converted Muslims are called “moriscos”. * |

| 1503 | 1503: Establishment in Seville of the Chamber of Commerce or House of Commerce with America. * |

| 1504 | 1504: Death of Isabella the Catholic, Queen of Castile. Her the place is occupied by Juana and Philip Handsome. * |

| 1505. | Spain begins to gain a foothold on coast of North Africa. ** |

| 1506 | 1506: Death of Philip the Handsome. Juana is announced crazy. Ferdinand of Aragon assumes the regency. * |

| 1512. | The Spaniards conquered the Upper Navarre. ** |

| 1513.09.01 | [America] Spaniard Vasco de Balboa with a handful people went on an expedition through the tropical jungle of the Isthmus of Panama.  September 25, he went to the Pacific coast of America in the Gulf of Panama (Balboa entered the water, brandishing his sword, and declared the ocean the property of the emperor). |

| 1516.01. | Spain. The king has died Ferdinand II . Charles ( Charles I , a.k.a. Charles V) from the Habsburg family, son of Juana of Castile and Philip the Handsome, inherits throne of Castile, Aragon, Navarre, Naples and America. * |

| 1516. | Netherlands annexed to Spain. |

| 1516. | [America] After the death of the king of the allied Mexico City of the city of Teshkoko, Moctezuma appointed his protege there, against the will local electors. Such a power policy sowed the seeds of a split, which was later used Hernando Cortes . |

1517. 09.17 09.17 | Young King Charles I landed in Spain. Jimenez, who until then ruled the country, retired to his diocese. |

| 1519. | Defeat of Francis I in the election of emperor. Election of Charles V of Spain emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. ** |

| 1519. | [America] The Spaniards landed on the continent and began their conquest Mexico. |

| 1519.11.08 | [America] Spanish conquistadors entered mexico city, Hernando Cortes met with Aztec king Moctezuma. |

| 1520.06.30 | [America] After eight months in mexico squad Hernando Cortes with fights made his way out of the city, while losing part of the soldiers, horses and everything captured gold.  |

| 1520.07.07 | [America] Spanish Army Hernando Cortes in alliance with The Tlaxcalans (Indians) defeated the Mexica at the Battle of Otumba. The battle took place in the open, and the Spaniards were able to use advantages of the cavalry. |

| 1520.07.29 | An uprising began in the cities of Castile Komuneros , caused by demands for money from the side of the king Charles I . |

| 1521. | The 1st war of Francis I began with Charles V and Henry VIII. It lasted 1521-1526. |

| 1521. | Partition Treaty of Worms empire of the Habsburgs. |

| 1521.04. | [America] Troop Hernando Cortes re set off on a campaign against Mexico City, now bypassing the lake, conquering allied forces along the way the city’s mexicans.  |

| 1521.04.28 | [America] Preparing to storm Mexico City, conquistadors launched 13 sloops into the water of the lake (to fight Indian canoe). |

| 1522.10.15 | Hernando Cortes received from King of Spain Charles letter – he was appointed governor and captain-general of New Spain. |

| 1522.12. | Hernando Cortes sent to three caravels from the port of Vera Cruz to Spain, part of what he captured in Mexico City gold owed to the king Carl . The cargo never reached its destination – it was captured by a French privateer and fell into treasury of the king of France. |

| 1524.11.14 | [America] Francisco Pizarro head 120 the Spaniards set sail on their first expedition along the Pacific coast South America.  |

| 1525.02.24 | Defeat of French troops at Pavia . Capture of Francis I. |

| 1526. | Treaty of Madrid. To Spain returns Burgundy and Tournai, France waives the right to Milan. ** |

| 1526.07.26 | The Spanish Queen confirmed the appointment Francisco Pizarro governor and captain-general of the Spanish colony overseas – New Castile, which was to be conquered. |

| 1526-1529. | Cognac League ( England , France , Pope, Venice, Florence). II war of Francis I with Charles V, which ended peace treaty at Cambrai. Francis I’s refusal claims to Italy and from suzerainty over Flanders and Artois. ** |

| 1930.01 | Francisco Pizarro at the head of the expedition sailed from Spain to the side Isthmus of Panama.  |

| 1531.01. | [America] Francisco Pizarro in charge expedition of three ships and 180 people left Panama. |

| 1531. | Spain began the conquest Inca Empire (1531-1535). |

| 1532. | [America] Inca Atahualpa defeated brother Huascar at the battle of Ambato, south of Quito. Then he attacked the city Tumebamba, killed its inhabitants and razed the city to the ground. |

| 1532.09.24 | [America] Francisco Pizarro out of Spanish settlement with drumming and flying banners at the head troops, consisting of 110 infantry and 67 horsemen. The detachment moved to towards the residence of Atahualpa near the city of Cajamarca. |

| 1534. | Spain. The Jesuit Order is founded. The Jesuit Order is founded. |

| 1536-1538. | III War of Francis I with Charles V Peace in Nice. France holds part of Piedmont. |

| 1542. | Spain. restored inquisition. |

| 1556.01.16 | Emperor Karl abdicated, divided the empire between his son Philip II and brother Ferdinand I**. |

| 1557-1559. | War of England in alliance with Spain against France. Liberation from the English of the city Calais, England’s last possession on the Continent. Peace treaty in Cato-Cambresi. |

| 1558. | Gravelinsky battle between French and Spanish troops. |

| 1560. | Spain. Capital of Spain moved to Madrid.  Expedition against Djerba Expedition against Djerbawas defeated. |

| 1566. | The fight has begun in the Netherlands for liberation from Spanish rule – the beginning of the bourgeois revolution in the Netherlands . |

| 1568. | Spain. Morris revolt. Swimming A.Mendagna de Neira to the Solomons islands. |

| 1570. | Spain. The execution of the writer and humanist A. Paleario. |

| 1571.10.07 | Spanish-Venetian Victory fleet over the Turks in the Gulf of Lepanto . |

| 1575. | State bankruptcy Spain. |

| 1579. | Seven North Dutch provinces made an alliance against Spain – Utrecht union .  |

| 1581. | Accession to Spain Portugal and breakaway of the Northern Netherlands. (See Art. Spanish-Portuguese Union ). |

| 1585. | Spain. Insurrection Aragonese peasants. |

| 1588. | The death of the “Invincible Armada”. ** |

| 1589-1598. | Spanish intervention in the French civil war. ** |

| 1590. | Spain. Revolt in Aragon. ** |

| 1596. | The British defeated the Spanish fleet in the harbor of Cadiz. |

| 1598. | France and Spain have concluded Vervenskiy world. |

Next: Spain in the 17th century. | |

The Spaniards went to Moscow

Napoleon first encountered the notorious “club of the people’s war” not in Russia, but in Spain. And, strictly speaking, it was not a club, but a Navaja guerrillas (Spanish partisans). In 1812, the Anglo-Spanish forces with dignity resisted the French in the Iberian Peninsula. But, a strange paradox, in cold Russia, a Spanish regiment also fought in the ranks of the Great Army, whose personnel were in no hurry to go over to the Russian side.

Until the spring of 1808, the Spanish kingdom was a true ally of France and even sent its contingents outside the Iberian Peninsula at the request of Napoleon. The largest of these contingents, numbering up to 15 thousand people, was stationed in Denmark and northern Germany.

However, in April 1808, Napoleon arrested the ruling Spanish Bourbon royal family and installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte (formerly the former King of Naples) on the throne. The answer was the people’s war that began in the country – the guerrilla.

Upon learning of these events, General Pedro La Romana, who commanded the Spanish troops in Denmark, managed to negotiate with the British. Having withdrawn most of the troops to the coast, he loaded them onto the ships of the British fleet and returned to Spain.

But not everyone is lucky. The Guadalajara and Asturian regiments, once surrounded, were forced to lay down their arms. The officers were taken under arrest as prisoners of war, and from the lower ranks the Joseph Napoleon regiment was formed, which they decided to keep away from Spain. Officer positions in it were filled by the French.

According to the staffing table of February 18, 1809, the regiment had an organization similar to the French linear infantry – that is, it consisted of five battalions, of which the first four were combat, and the fifth was a reserve.

In 1812, the regiment was divided into two parts and distributed among different army corps. Apparently, this was due to the fact that Napoleon did not believe in the reliability of the Spaniards and expected to use them for the auxiliary needs of the army (guarding corps, communications, garrison service, etc. ).

).

By the beginning of the Russian campaign, the 1st and 4th battalions of the regiment (35 officers and 1294 lower ranks) under the command of the second major Jean Doreyer were in the 1st brigade of the 14th infantry division of divisional general Count Jean Broussier of the Fourth Army Corps; The 2nd and 3rd battalions of the regiment (47 officers and 1678 lower ranks) under the command of Colonel Baron Jean Baptiste de Tschudi were in the 3rd Brigade of the 2nd Infantry Division of Divisional General Count Louis Friant of the First Army Corps.

At the same time, the overall command of the regiment remained with Lieutenant General Juan de Kindelan, the highest-ranking of the Spanish officers who recognized the authority of Joseph Napoleon. The French awarded him the rank of divisional general.

In the eyes of domestic and Western historians, the reputation of the Spanish regiment was, to put it mildly, unimportant. Desertion and smaller misdemeanors literally trailed behind his soldiers wherever they went.

Here is how the French officer Coignet describes the episode connected with the Spaniards from the campaign of 1812, whose share fell on the difficult task of collecting and escorting soldiers who had lagged behind their battalions and regiments: “One burnt forest lay to the right of our path, and when we caught up with it, I saw that part of my battalion set off just there, into this burnt forest. I gallop to bring them back. What was my surprise when suddenly the soldiers turn to me and start shooting at me! Of course, I had to refuse further attempts.

The conspirators were from the soldiers of Joseph Napoleon, all Spaniards without exception. There were 133 of them; not a single Frenchman got involved among these brigands. Returning to my detachment, I gathered the soldiers in a circle and told them: “I have to report what happened to the authorities. Be French and follow me. I will not watch in the rear; it is your business. Alignment to the right!

In the evening, I finally get out of the accursed forest and drive up to the village, where the cavalrymen were stationed, led by a colonel, who guarded the stage at the crossroads and directed the troops passing by. I go to him and report. The colonel stationed my battalion, then ordered the Jews and an interpreter to be brought in. On the basis of my reports, he tries to imagine how far away my deserters may now be, what village they might have ended up in. 50 cavalry riflemen were sent; Jews accompany them. Halfway they met robbed peasants seeking protection. At midnight, the riflemen drove up to the village, surrounded it and took away all the Spaniards who were found sleeping there. The Spaniards were seized, disarmed, and their guns were put in a cart. The deserters themselves were also placed on carts; each of them was carefully guarded.

I go to him and report. The colonel stationed my battalion, then ordered the Jews and an interpreter to be brought in. On the basis of my reports, he tries to imagine how far away my deserters may now be, what village they might have ended up in. 50 cavalry riflemen were sent; Jews accompany them. Halfway they met robbed peasants seeking protection. At midnight, the riflemen drove up to the village, surrounded it and took away all the Spaniards who were found sleeping there. The Spaniards were seized, disarmed, and their guns were put in a cart. The deserters themselves were also placed on carts; each of them was carefully guarded.

In the morning at 8 o’clock 133 Spaniards were brought to the place of the cavalry camp. The fetters were removed from them; the colonel ordered them to line up and addressed them with the words: “You have behaved badly; line up first. Are there any sergeants or corporals among you to line you up in the usual order?” Here are two sergeants pointing to their galloons hidden under their overcoats. “Stand here. Are there corporals? Three perform. “Stand here. No more? Fine. Now you, the rest of you, take out the tickets.”

“Stand here. Are there corporals? Three perform. “Stand here. No more? Fine. Now you, the rest of you, take out the tickets.”

Who took out a white ticket, departed in one direction; who took out the black one went to another. When the procedure was over, the colonel said: “You stole, you set fire to, you shot at your officer; the law condemns you to death, now you will be subjected to this punishment. I could have you all shot, but I spare half. Let this be an example! Major, order your battalion to load their guns. My adjutant will give the order to fire now.” 62 people were shot. God! What a scene it was! With a broken heart, I immediately left. But the Jews were happy. That’s what I had to update my rank of lieutenant! The next day I’m leaving for Vitebsk.

In fact, the scale of desertion was not so colossal, although, undoubtedly, it exceeded the average level throughout the Grand Army. It is known that before the Battle of Borodino, there were 990 people in the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the regiment, and about 770 people in the 1st and 4th battalions, and in both cases the loss of personnel was mainly due to non-combat losses.

Regimental officer Rafael de Llansa describes in his diary the events of September 5, 1812 and the battle at the Kolotsk Monastery against the Russian rearguard under the command of Lieutenant General Pyotr Petrovich Konovnitsyn: “During this bloody battle, my battalion participated in the offensive. At half past ten we were attacked by cavalry, which, by order, were to be broken and destroyed. We were very lucky that one volley stopped her. Obviously, under the cover of night, the Russians thought we were stronger than we really were. What a great moment it was to go over to the side of the Russians with all the banners! Two Spanish regiments were at the forefront of the French army throughout the battle. I have no doubt that we were exposed to the most desperate risk for our speedy destruction. If we felt the slightest hope that the Russians could accept us, we would instantly surrender to them.

Two days later, in the battle of Borodino, the regiment remained in the rear, but for four hours suffered losses from Russian artillery fire. After the battle, Llança was struck by Napoleon’s order to leave the wounded on the battlefield: “What a sad sight, especially considering that the next day thousands of people were thrown onto the battlefield as a reward for their courage!”

After the battle, Llança was struck by Napoleon’s order to leave the wounded on the battlefield: “What a sad sight, especially considering that the next day thousands of people were thrown onto the battlefield as a reward for their courage!”

But the worst began after the departure from Moscow.

From the diary of Castellane, who was at the Main Apartment, we also learn about the self-sacrifice of the Spanish soldiers, shown when rescuing their comrades in arms in the battle of Vyazma on November 3, 1812: “The imperial headquarters was moved to Fominsky. From Malaya Vyazma we set off for Kubinskoye; this post is occupied by the Westphalian battalion, numbering only a hundred men; he had lost forty men at the mill the day before. Shortly after our arrival, the Cossacks appeared. With a bang they rushed to the convoy with the wounded; The soldiers who escorted him behaved badly.

I asked for fifty hunters in Joseph Napoleon’s regiment to rush 1/2 mile ahead and save as many people as possible; called willing from this brave regiment. These fifty grenadiers rushed at the enemy at a run, and we saved a hundred people, well-armed, hiding in the forest, without firing a single shot; I even felt sorry for such rogues. On the road we saw an abandoned van in which two unfortunate wounded were left.”

These fifty grenadiers rushed at the enemy at a run, and we saved a hundred people, well-armed, hiding in the forest, without firing a single shot; I even felt sorry for such rogues. On the road we saw an abandoned van in which two unfortunate wounded were left.”

Next, we will again give a fragment from de Llansa’s diary. “In punishment for allowing an ambush of two thousand Cossacks to capture all our artillery at dawn, my unit was ordered to escort [one unit]. The Cossacks jumped out of the forest, cut off the column, killed everyone they captured. Confusion broke out in the convoy. The emperor at that time was passing very close. His guardsman, three adjutants and one general were wounded. <...> We would not have gotten off so easily if the Neapolitan king, who was located nearby with all his cavalry, had not quickly reported the danger in which his master was, and had not advanced with ten thousand cavalrymen.

From the works of I. N. Vasiliev, dedicated to the retreat of the Great Army, we learn how courageously the soldiers of the battalions of the regiment acted in the second battle near Krasnoy (November 15–18, 1812): ), despite the fire of Russian guns, crossed the Losmina ravine and rushed to the Russian batteries: two Spanish battalions on the left flank, the 48th line on the right.

“The swiftness with which this attack was carried out would have been crowned with success, since the French had already mastered several guns, but at that time Paskevich approached with his division, the enemy was overturned with bayonets and thrown back into the ravine.”

Then Llansa talks about the piles of loot abandoned by the soldiers of the Grand Army and complains that the Poles stole his own luggage.

Wounded de Llansa, however, gathered a detachment of soldiers of different nationalities who had fallen behind their units, and surrendered to the first Russian general they met – in this case it was the commander of the Cuirassier Corps, Lieutenant General Dmitry Vladimirovich Golitsyn.

In his memoirs, he cites the following dialogue:

“Sir, I am an unfortunate Spaniard…

– Spaniard? My emperor will not take the Spaniards as prisoners. Our countries are bound by a close alliance. Russian troops will protect every Spaniard who gets to us.

“In that case, sir, there is no need for further talk. I, my officers and soldiers ask you to take us under the protection of your emperor, your father and general. And as for this crowd, you can dispose of it as you see fit.

190 Spanish officers and soldiers managed to get out of Russia.

The reserve battalion of the regiment, abolished in 1810, was restored in September 1812 in Maastricht. In 1813, the remnants of the 1st and 4th battalions gathered in Glogau, and the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the regiment – in Stettin.

However, the surviving soldiers and officers were only enough for two full-fledged battalions. The first battalion in 1813 participated in battles with the allies at Lützen, Bautzen, Dresden, Leipzig and Hanau, after which he withdrew with the remnants of the Napoleonic army to the territory and was reorganized into the “regiment of Spanish pioneers”. It was disbanded after the abdication of Napoleon, along with the 2nd battalion, whose personnel until April 1814 was under siege in Magdeburg.

The hides they tan and beat with stones until they are soft. They fight with bows and arrows. … They cultivate corn, beans, and calabashes.

The hides they tan and beat with stones until they are soft. They fight with bows and arrows. … They cultivate corn, beans, and calabashes. Watch it now, Wondrium.

Watch it now, Wondrium.