The taino: What Became of the Taíno? | Travel

Columbus and the Taíno – Exploring the Early Americas | Exhibitions

Home | Exhibition Overview | Exhibition Items | Public Programs | Learn More | Interactive Presentations | Acknowledgments

Sections: Pre-Contact America | Explorations and Encounters | Aftermath of the Encounter

Return to Explorations and Encounters List Next Section: Cortés and the Aztecs

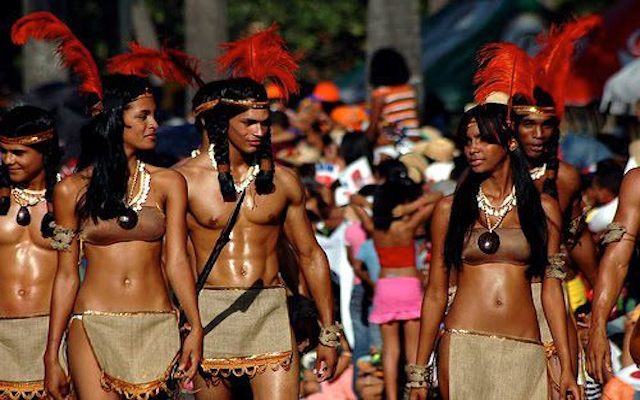

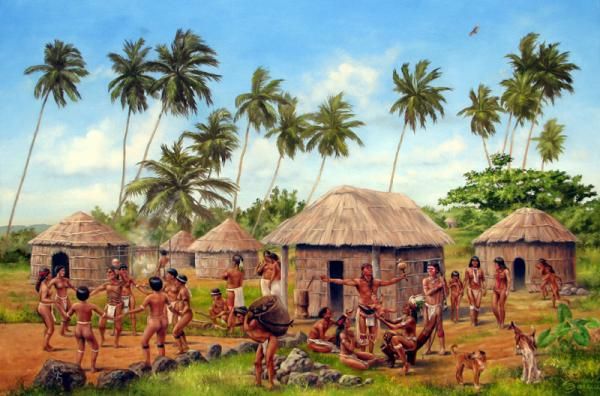

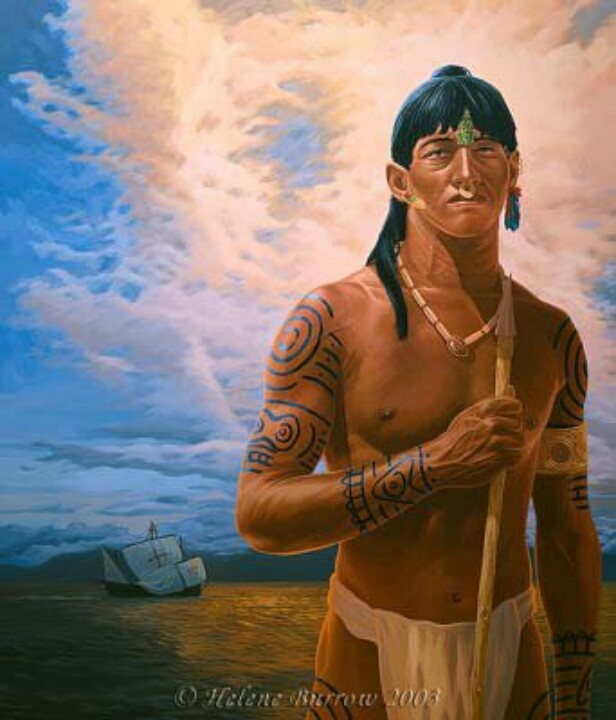

When Christopher Columbus arrived on the Bahamian Island of Guanahani (San Salvador) in 1492, he encountered the Taíno people, whom he described in letters as “naked as the day they were born.” The Taíno had complex hierarchical religious, political, and social systems. Skilled farmers and navigators, they wrote music and poetry and created powerfully expressive objects. At the time of Columbus’s exploration, the Taíno were the most numerous indigenous people of the Caribbean and inhabited what are now Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. By 1550, the Taíno were close to extinction, many having succumbed to diseases brought by the Spaniards. Taíno influences survived, however, and today appear in the beliefs, religions, language, and music of Caribbean cultures.

Taíno influences survived, however, and today appear in the beliefs, religions, language, and music of Caribbean cultures.

Columbus’s Account of 1492 Voyage

After his first transatlantic voyage, Christopher Columbus sent an account of his encounters in the Americas to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Several copies of his manuscript were made for court officials, and a transcription was published in April 1493. This Latin translation was published the same year. In reporting on his trip to his sovereigns, Columbus wrote:

There I found very many islands, filled with innumerable people, and I have taken possession of them all for their Highnesses, done by proclamation and with the royal standard unfurled, and no opposition was offered to me.

Enlarge

Christopher Columbus (1451–1506). Epistola Christofori Colom (Letters of Christopher Columbus). Rome: Stephan Plannck, after April 29,1493. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (048. 00.00, 048.00.01, 048.00.02, 048.00.03)

00.00, 048.00.01, 048.00.02, 048.00.03)

Columbus’s Voyage and the New World

This edition of the Columbus letter, printed in Basel in 1494, is illustrated. The five woodcuts, which supposedly illustrate Columbus’s voyage and the New World, are in fact mostly imaginary, and were probably adapted drawings of Mediterranean places. This widely published report made Columbus famous throughout Europe. It earned him the title of Admiral, secured him continued royal patronage, and enabled him to make three more trips to the Caribbean, which he firmly believed to the end was a part of Asia. Seventeen editions of the letter were published between 1493 and 1497. Only eight copies of all the editions are extant.

Enlarge

Christopher Columbus. De Insulis nuper in Mari Indico repertis in Carolus Verardus: Historia Baetica. Basel: I.B. [Johann Bergman de Olpe], 1494. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (048. 01.00, 048.01.01, 048.01.02, 048.01.03)

01.00, 048.01.01, 048.01.02, 048.01.03)

Columbus’s Book of Privileges

On January 5, 1502, prior to his fourth and final voyage to America, Columbus gathered several judges and notaries at his home in Seville to authenticate copies of original documents in which Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand had granted titles, revenues, powers, and privileges to him and his descendants. These thirty-six documents are popularly called Columbus’s “Book of Privileges.” Four copies of his “Book” existed in 1502, including one now in Paris from which the elaborate facsimile shown here was made. This publication was one of a number of major documentary projects commemorating the 400th anniversary of the first Columbus voyage in 1892.

Enlarge

Benjamin Stevens, first comp. and ed. Christopher Columbus, His Own Book of Privileges, 1502. London: Chiswick Press, 1893. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (050. 00.00, 050.00.01, 050.00.02, 050.00.03)

00.00, 050.00.01, 050.00.02, 050.00.03)

- Watch the video

Columbus Biography Written by His Son

Fernando Colón was born in Córdoba, Spain, in 1488 and spent his early years there with his mother. As a youth, he traveled to the New World with his father on Columbus’s fourth voyage. As an adult, Fernando became a scholar and built a large personal library using the income from his father’s legacy. Fernando wrote this biography in defense of his father in about 1538.

Enlarge

Fernando Colón (1488–1539). Historie del sig. don Fernando Colombo, nelle quali s’hà particolare, & vera relatione della vita, & de’ fatti dell’ammiraglio don Christoforo Colombo suo padre (History by Don Fernando Columbus . . . Don Christopher Columbus, his father). Milan: Girolamo Bordoni, [1614]. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (051.00.00, 051.00.02, 051.00.03)

Columbus’s Legacy

The grants of privileges and property bestowed on Christopher Columbus by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella became the subject of ongoing litigation between his descendants and the Spanish crown that lasted for centuries. The dispute was finally settled in 1796 in favor of Columbus’s descendants. This collection of printed documents, which includes extracts of Columbus’s will, relates to a dispute over the line of inheritance of one of the explorer’s estates in the Americas.

The dispute was finally settled in 1796 in favor of Columbus’s descendants. This collection of printed documents, which includes extracts of Columbus’s will, relates to a dispute over the line of inheritance of one of the explorer’s estates in the Americas.

Enlarge

Christoper Columbus. Por parte del conde de Gelues, de doña Francisca Colon, de don Christoual Colon, y de don Baltasar Colon, se suplica a V.m. que cerca de la executoria que la parte de la marquesa de Guadaleste pide, de la que llama sente[n]cia, dada en su fauor por el consejo Real de las Indias. [Spain: s.n., ca. 1586]. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (052.00.00, 052.00.01, 052.00.02, 052.00.03)

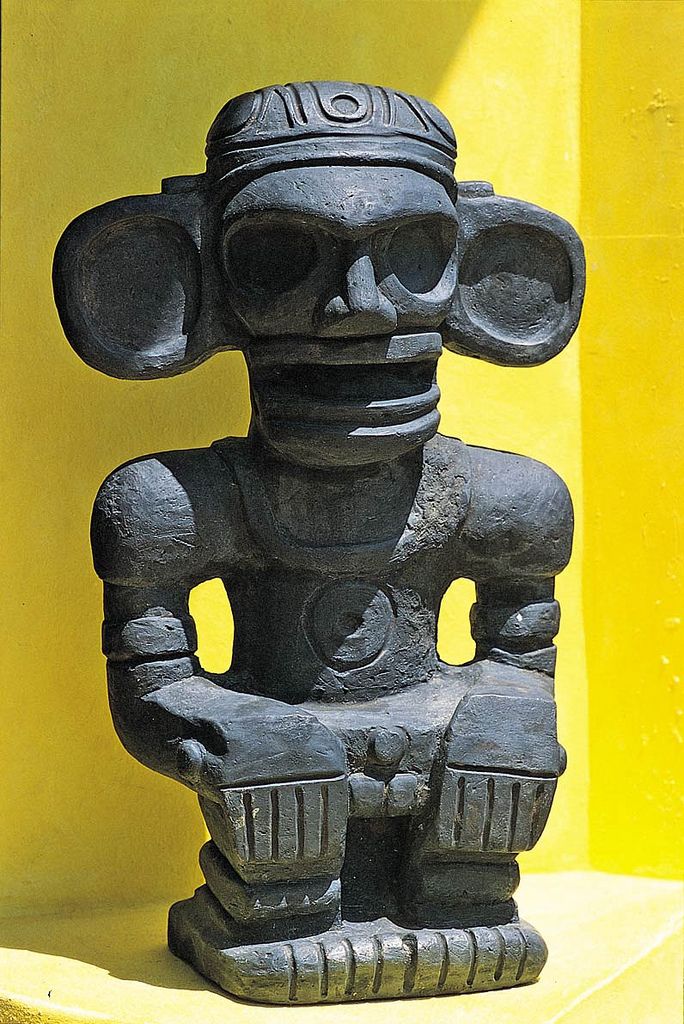

Ceremonial Wooden Stool

Preserved Pre-Columbian duhos (ceremonial wooden stools) from the Caribbean region are exceedingly rare because they are usually found only in dry highland caves. There are two basic types: low horizontal forms with concave seats, such as this one, and stools with long curved backrests. Scholars differ as to the function of the stools. Some believe they represented seats of authority. Others think they served as altars for votive offerings. Still others argue that the Taíno peoples used them as ceremonial trays for making cohoba, a hallucinogenic snuff prepared for shamanistic rituals.

Scholars differ as to the function of the stools. Some believe they represented seats of authority. Others think they served as altars for votive offerings. Still others argue that the Taíno peoples used them as ceremonial trays for making cohoba, a hallucinogenic snuff prepared for shamanistic rituals.

Enlarge

Ceremonial wooden stool (“Duho”). Haiti.Taíno, AD 1000–1500. Carved lignum vitae. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (054.00.00). ©Justin Kerr, Kerr Associates

Back to Top

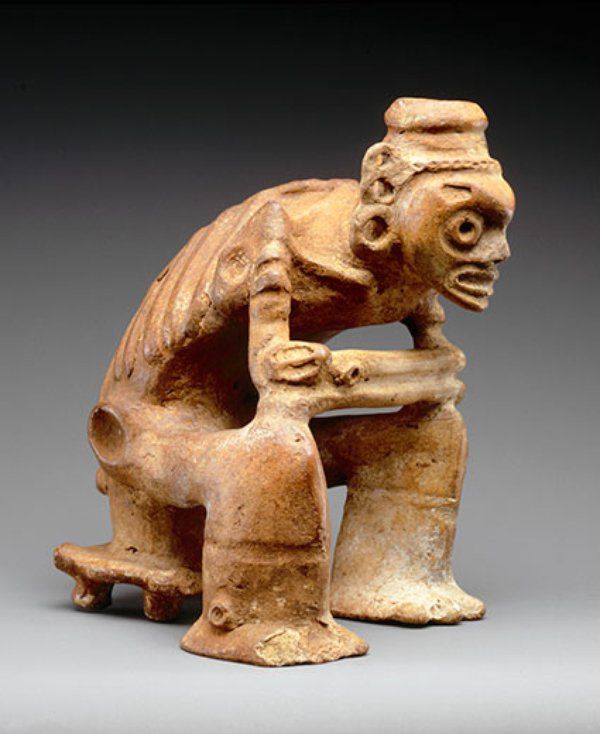

Taíno Amulet

The Taíno, a subgroup of the Arawakan Indians from northeastern South America, inhabited the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico). The Taíno created a complicated religious system that included a hierarchy of deities, which included Yucahu, the supreme Creator and the lord of cassava and the sea and Atabey, the goddess of fresh water and human fertility, as well as Yucahu’s mother. The Taíno believed that zemis, gods of both sexes, represented by both human and animal forms, provided protection.

The Taíno believed that zemis, gods of both sexes, represented by both human and animal forms, provided protection.

1 of 5

Enlarge

Shell Amulet. Haiti or Dominican Republic. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.01)

Enlarge

A crouching figure amulet. Puerto Rico (?). Taíno, AD 1000–1500. Marble. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.02)

Enlarge

In the form of a crouching figure with head turned to the side and grasping a stylized figure amulet. Puerto Rico (?). Taíno, AD 1000–1500. Stone. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.03)

Enlarge

Two anthropomorphic amulet figures (zemis) in a ritual squatting position possibly the wind god and the a smaller frog avatar.

Haiti. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.04)

Haiti. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.04)Enlarge

Conch shell ornament representing a humanoid face. Puerto Rico. Taíno, AD 1000–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.05)

Spatula Used for Purging

This long, gracefully curved spatula was used for purging before taking the sacred trance-inducing cohoba, a powerful snuff of nicotine-rich tobacco. The earlobes and eye sockets once held inlays, perhaps of gold leaf or shell.

Enlarge

Effigy bone vomitive spatula. Greater Antilles. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved manatee rib. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (056.00.00). Photo ©Justin Kerr, Kerr Associates

Heart-Shaped Vessel

This intact pottery container is a heart-shaped bottle covered with complex iconography, including female and male attributes. The two lobes represent female breasts and the neck, a phallus. Scholars believe these vessels were water containers used in rituals and ceremonies.

The two lobes represent female breasts and the neck, a phallus. Scholars believe these vessels were water containers used in rituals and ceremonies.

Enlarge

Heart shaped vessel. Dominican Republic. Taíno, AD1000–1500. Ceramic. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (057.00.00)

Early Description of the New World

Antonio Nebrija, best known for attempting to standardize the Castilan dialect of Spanish as a written language, had many geographical interests. Advisor to Columbus’s son Ferdinand Colón, Antonio Nebrija attempted to update the geography of Ptolemy, Strabo, Pliny, and other classical sources “to the reality of our times” and to include information from the discoveries of contemporary European explorers. This book contains one of the earliest descriptions of the New World.

Enlarge

Antonio Nebrija. Introductorium in Cosmographiae libros [Introduction to cosmography]. Salamanca: Printer of Nebrija, ca. 1498. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (53.00.00, 53.00.01, 53.00.02, 53.00.03)

Salamanca: Printer of Nebrija, ca. 1498. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (53.00.00, 53.00.01, 53.00.02, 53.00.03)

Discover!

Chronicling the New World

Gonzolo Oviedo sailed in 1514 on the first of his many journeys to America, where he compiled detailed descriptions and woodcut illustrations of products and goods found in the New World. The Spaniard introduced Europe to an enormous variety of previously unheard of “exotica,” including the pineapple, the canoe, smoking tobacco, the manatee, and hammocks. Along with Perro Mártir de Angleria and Bartolomé de las Casas, Oviedo was one of the first European chroniclers of New World goods.

Enlarge

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557). La historia general delas Indias (The general history of the Indies). Seville: Cromberger, 1535. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (067.00. 00, 067.00.01, 067.00.02, 067.00.03)

00, 067.00.01, 067.00.02, 067.00.03)

Girolamo Benzoni

In 1541, Girolamo Benzoni left his native Milan for a fifteen-year trip through South and Central America. He published this account of his travels in 1565. Shocked by experiences of Spanish cruelty toward the Indians, Benzoni denounced the mistreatment. He also criticized importation of African slaves. Although Benzoni has been criticized for exaggeration, his work provides a compact history of the Americas from the arrival of Columbus to the conquest of Peru, from firsthand perspective not colored by Spanish bias. His crude woodcut illustrations give a glimpse of indigenous life before it was altered by European civilization.

Enlarge

Girolamo Benzoni (b. 1519). La historia del mondo nuovo di M. Girolamo Benzoni Milanese [The history of the New World of Mr. Girolamo Benzoni of Milan]. [Venice: F. Rampazetto, 1565.] Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (068. 00.00, 068.00.01, 068.00.02, 068.00.03)

00.00, 068.00.01, 068.00.02, 068.00.03)

Back to top

Return to Explorations and Encounters List Next Section: Cortés and the Aztecs

Home | Exhibition Overview | Exhibition Items | Public Programs | Learn More | Interactive Presentations | Acknowledgments

Sections: Pre-Contact America | Explorations and Encounters | Aftermath of the Encounter

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, meet the survivors of a ‘paper genocide’

The people we now call Taíno discovered Christopher Columbus and the Spaniards. He did not discover us, as we were home and they were lost at sea when they landed on our shores. That’s how we look at it—but we go down in history as being discovered. The Taíno are the Arawakan-speaking peoples of the Caribbean who had arrived from South America over the course of 4,000 years. The Spanish had hoped to find gold and exotic spices when they landed in the Caribbean in 1492, but there was little gold and the spices were unfamiliar. Columbus then turned his attention to the next best commodity: the trafficking of slaves.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Maritza Luz Feliciano Potter, 38

“Through marriage certificates, baptismal records and a scant few census reports, I was able to identify a few family members (in the mid 1700s) who were officially ‘identified’ as Negro one year, but categorized as ‘Indio’ just a few years prior.While I don’t deny my European or African ancestry, I deeply feel it’s long due that my family relearns, remembers, and reclaims our birthrights as Indigenous Boricuas [Puerto Ricans]. We Are Taíno! We are still here!”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

Due to harsh treatment in the gold mines, sugarcane fields, and unbridled diseases that arrived with the Spanish, the population rapidly declined. This is how the myth of Taíno extinction was born. The Taíno were declared extinct shortly after 1565 when a census shows just 200 Indians living on Hispaniola, now the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The census records and historical accounts are very clear: There were no Indians left in the Caribbean after 1802. So how can we be Taíno?

The census records and historical accounts are very clear: There were no Indians left in the Caribbean after 1802. So how can we be Taíno?

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Mercedes Garcia, 36

“Growing up, my grandmother kept telling me that I was Taíno, and that no matter where I was in the world, that was who I was. I didn’t fully understand what Taíno meant until I read about the Taíno and Arawak in the encyclopedia. It broke my heart to read that my people were extinct.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

Few historians have taken a deep critical look at these census records, even though Indians kept appearing in reports, wills and testaments, and marriage and birth records throughout the Colonial period and beyond. We survived because many of our ancestors ran off into the mountains. When the inquisition began in Spain in 1478, any Jew that did not want to be tortured or murdered had only to convert to Catholicism. They became known as conversos (converts). This practice was also applied to Taíno Indians. Then, after 1533, when Indian slaves were “granted” their freedom by the Spanish monarchy, any Spaniard who was reluctant to let their Taíno slaves go would simply re-classify them as African. Throughout, Spanish men in the Caribbean were marrying Taíno women. Were their children not Taíno?

They became known as conversos (converts). This practice was also applied to Taíno Indians. Then, after 1533, when Indian slaves were “granted” their freedom by the Spanish monarchy, any Spaniard who was reluctant to let their Taíno slaves go would simply re-classify them as African. Throughout, Spanish men in the Caribbean were marrying Taíno women. Were their children not Taíno?

Paper genocide means that a people can be made to disappear on paper. The 1787 census in Puerto Rico lists 2,300 pure Indians in the population, but on the next census, in 1802, not a single Indian is listed. (The photography project here reimagines that census data.) Once something is put down on paper there is almost nothing you can do to change it. Every encyclopedia has Columbus’s accounts of his, and that he called us Indians and that not a single Indian was left in the Caribbean shortly after. No matter how you may look physically or assert your identity, you are extinct. This is paper genocide: a narrative created by the conquerors and perpetuated by every subsequent researcher.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Gypsie RunningCloud, 48

“I had ingrained in me from the time I was a little one by the elders in my family the notion of maintaining an absolute radio-silence concerning our indigeneity. We were acculturated to the idea that we must never, ever reveal ourselves to be indigenous peoples; this notion even extended to simply nodding politely when strangers stated that we ‘resembled’ native peoples, but my cousins and I were absolutely never to publicly acknowledge our Indigenous heritage.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

I was born in the town of Jaibon in the Dominican Republic. As a young boy growing up in the United States, I had read that there was not a single drop of indigenous blood in the Caribbean, that every single Indian had been killed off. But people like myself always identified as indigenous. We always knew we had Indian ancestry.

We always knew we had Indian ancestry.

In the early ‘90s we began meeting up at different native events such as pow-wows and festivals. We began a reclamation movement to try to preserve what we knew of the language and surviving practices.

Later DNA studies started to show that people in the Caribbean did indeed have Native American mitochondrial DNA: 61 percent of all Puerto Ricans, 23 to 30 percent of Dominicans and 33 percent of Cubans. That is a high number of genetic markers for a supposedly extinct people. In 2016, a Danish geneticist pulled ancient DNA from a tooth found in a 1,000-year-old skull from the Bahamas. This tooth had a full strand of Taíno DNA. Would we match? Of 164 Puerto Ricans tested, every single one matched the Taíno DNA. (Get the facts on whether DNA tests can reunite immigrant families.)

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Rene J. Perez, 33

Perez, 33

“When I was 4 or 5 I asked my mother ‘What are we?’ to which she replied, ‘Taíno.’ When I asked her what Taíno was she replied ‘Indios’ which in Spanish means ‘Indian’ so I always thought I was from India. Of course, as I grew older I learned that my mother meant natives from the Caribbean.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Juliet Diaz Bawainaru, 38

“It’s who we always knew we were. Being Taíno was never a secret to our family in Cuba.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

All along, we have been writing ourselves back into history. The internet is our most powerful tool. Today, we have a whole cadre of young scholars who identify as Taíno. Asking new questions and questioning old answers, they are writing us back into history. Some books have stopped using the word extinction to describe us as well.

Some books have stopped using the word extinction to describe us as well.

Another way we assert our identity is by attacking the census records. For a long time, there was no Indian option for people from Latin America—you were either Hispanic, white, black, or a mixture. When the Indian or indigenous option was placed in the Puerto Rican census, 33,000 people identified as Indian. Our identities have always been hidden in plain sight. That’s what this photography project reflects.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Kayla Anarix Vargas-Estevez, 17

“It is all I’ve ever known.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Eric Alexie Cruz, 48

“In 2014, I worked on a documentary film featuring Native Americans from Oklahoma called Spirit Roads. ..I connected with someone during my time there and wanted to learn more of my heritage. The more I learned, the more I saw that the old traditions that my family followed were traced back to the Taíno.”

..I connected with someone during my time there and wanted to learn more of my heritage. The more I learned, the more I saw that the old traditions that my family followed were traced back to the Taíno.”

Photographs by Haruka Sakaguchi

We want the world to know that the Taíno people were not exterminated. We played an important role in the formation of our island nations. For us, learning this story is like finding a long lost relative, a piece of yourself that you knew nothing about. When I realized that much of our oral traditions, material culture, spirituality, and language is indigenous, I realized just how triumphant the Taíno people were. (Here’s how mapmakers are helping indigenous people defend their lands.)

I remember when I first came home as a child after discovering Columbus. I was so excited and I’d drawn a picture of the three little ships. When I got home my mother told me the real story. I was shocked. Millions of people died because of his thirst for gold and recognition. To get to a point today where the population at large, not just Caribbean or indigenous people, agree that he’s not someone to be celebrated is very gratifying.

To get to a point today where the population at large, not just Caribbean or indigenous people, agree that he’s not someone to be celebrated is very gratifying.

Whenever I contemplate my history and think of the atrocities committed by the Spaniards I wonder: What were the grandmothers and mothers doing as they watched their children, siblings, and parents slaughtered and raped, their villages pillaged and plundered? They must have prayed hard, as all suffering people do. But what happened to those prayers? Did they vanish in the air like smoke from a camp fire? Then it hits me: we the descendants are their prayers. We’ve come back to make things right, to tell our story.

Chief Jorge Baracutei Estevez is a retired Program Specialist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. He was part of the team that put together the museum’s first Taíno exhibit. Now, he serves as the head of Higuayagua, a Taíno organization in New York and the Caribbean. He is working on documenting the oral histories of elderly Taíno.

Haruka Sakaguchi is a Japanese photographer based in New York. She and Chief Jorge Estevez created a hypothetical census entry to reimagine what an individual entry would have looked like in 1802, the year when the Indio population in Puerto Rico dropped from a recorded 2,312 (in 1797) to none. Sakaguchi asked her subjects to pose in clothing they felt encapsulated their identity.

Taino Indian Museum – GoDominicanRepublic.com

The exhibits displayed in the museum correspond to the size of the human body. Here the Taíno Indians tell their story, beginning with the meeting with the Spanish conquistadors. The guided tour of the museum takes about an hour; upon completion, participants can purchase souvenirs in the souvenir shop. Location: Los Robalos, Sanchez-Samana Highway.

My location

Google MapsGet directions

All Translation PrioritiesOptional

Title

Avenida de la Marina Boulevard

Any photographer will appreciate the picturesque bay of Samana. It seems that the whole life of the town of Santa Barbara de Samana is concentrated on the waterfront. Locals and tourists relax on shady benches overlooking the bay, watching the boats moored here, always ready to rush into the blue expanses of tourists or fishermen.

It seems that the whole life of the town of Santa Barbara de Samana is concentrated on the waterfront. Locals and tourists relax on shady benches overlooking the bay, watching the boats moored here, always ready to rush into the blue expanses of tourists or fishermen.

Samana, History and Culture, Family Vacation

Samana Bay

One of the most beautiful bays in the Dominican Republic, it is the main starting point for daily boat trips to Los Haitises National Park, Cayo Levantado Island, and Samana’s famous whale watching expeditions. Small mangroves, underwater sea grasslands and corals are found in the bay, as well as turtles and manatees, and from mid-January to mid-March, humpback whales.

Samana, Airports and Seaports, History and Culture, Seaports, Wildlife Watching, Family Fun

El Limon Falls

To get to El Limon Falls, you have to travel 2.5 kilometers through dense forest, either on horseback or on foot. But along the way you will be able to observe the local flora and fauna to your heart’s content. In addition, the waterfall can be reached by crossing the canyons of the river. El Lemon.

In addition, the waterfall can be reached by crossing the canyons of the river. El Lemon.

Samana, Waterfalls, Canyoning + Rope Walking, Horseback Riding, Wildlife Watching, Bird Watching, National Park + Conservation Areas, Hiking, Adventure & Ecotourism, Family Fun, Excursions

Marine Mammal Sanctuary

Thousands of tourists come to Samana every year to see the main spectacle of the season – flocks of humpback whales returning to the Atlantic waters of the bay to find a mate and acquire offspring. In 1986, this area was officially recognized as a Marine Mammal Sanctuary.

Samana, Wildlife Watching, National Park + Conservation Areas, Adventure & Ecotourism, Family Fun

Zip Line To Kanyo Ondo

Just 20 minutes east of Sanchez, the zip line will give you the amazing opportunity to ride through the protected Los Haitises National Park. You will fly over the emerald pools of the Jibales River, on which the Paraíso Caño Hondo Hotel is located.

Samana, Zipline, Family Fun, Excursions

Zipline In Samana

Samana has the longest and most exciting zipline in the Dominican Republic, right above the green hills of El Valle. Thanks to the built-in braking system, you will be able to exit in pairs, flying at an altitude of 122 m, while in some places the speed of movement reaches 64 km / h.

Samana, Zipline, Adventure & Ecotourism, Family Fun, Excursions

Zipline In Juana Vincente

Ten 1750m ziplines passing through 20 intermediate platforms will allow you to enjoy the stunning topography of the Samana peninsula from a bird’s eye view. You will fly over rolling hills, dense rainforests and panoramic views of Los Haitises National Park.

Samana, Zipline, Family Vacation

Cayo Levantado

Cayo Levantado, a small, picturesque island located just 5 km from Samana Bay, is famous for palm-fringed beaches with white sand shining in the sun. Here you can swim, sunbathe, ride a kayak or paddle board, and also enjoy dishes from freshly caught fish.

Samana, Boat Attractions, Islands + Shoals, Beaches, Adventure & Ecotourism, Family Fun, Excursions

La Playita

Not far from Las Galeras is La Playita – a cozy white crescent-shaped beach that you will surely enjoy its shallow waters, a small restaurant overlooking the crystal clear turquoise waters and the picturesque Rincon beach seen in the distance.

Las Galeras, Samana

Start typing and press Enter to search:

Taino Cave (Macao Cave) – IDominican Republic Uveroalto, but few know how to get there.

A stone complex of a cave type with a lake and an underwater hall hidden from ordinary visitors…

An underground lake with clear cool bright blue water.

The cave is surrounded by colorful local settlements. There are many buggy and ATV bases nearby, one of the most popular and inexpensive off-road excursions in the Dominican Republic starts in this area.

Therefore, the road to the cave is not equipped.

If you have reached the location of the cave, then signs and a large cluster of shops with tourist goods will point to it.

The entrance to the cave is free. A stone vault goes to the left, and the descent to the right will lead you to an underground lake.

You can swim only by jumping from a ledge, and climb up by pulling yourself up on ropes lowered into the water.

This is a mesmerizing place where every sound echoes and stalactites, stalagmites and stalagmas surround you.

The water in the lake is fresh and has great transparency, as well as visibility up to 20 meters. Therefore, the cave, including, was chosen by divers.

The water temperature is about 22-25 C, the depth, according to various sources, varies from 5 to 10 meters.

The main underwater tunnel covers an area of about 50 meters. At the same time, locals claim that experienced divers made their way further, through a narrow passage that led them to a hall with snow-white stalactites.

The underwater world here is not very diverse. But the stone park is impressive. You can also see the endemic cave crab here.

Taino Cave History

The true history of the cave is unknown. However, local residents claim that the Taino Indians, the indigenous inhabitants of the island of pre-Columbian times, performed rituals here earlier.

This is evidenced by the remains of ancient dishes found at the bottom of an underground lake.

The Indians also used the cave lake as a source of drinking water.

Where Taino Cave is located

Taino Cave fascinates with its beauty and is located very close to the main resorts of the Dominican Republic – Bavaro, Punta Cana and Uveroalto.

However, many travelers do not find the cave on the maps, but all because the name confuses them. The original name is Taino Cave, but on the maps it is designated as Macao Cave – Macao Cave (Cueva Macao).

Haiti. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.04)

Haiti. Taíno, AD 700–1500. Carved shell. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (055.00.04)