Arawak puerto rico: What Became of the Taíno? | Travel

The Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project: Celebrating Taíno Culture

Popular history holds that shortly after Christopher Columbus arrived to the Caribbean in 1492, the Arawakan-speaking Native people known as the Taíno were completely destroyed by slavery, European disease, starvation, and war. In Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and the Lesser Antilles, 90% of the Native population may have died within a half century. However, their story did not end there. The story of the Taíno is a story of survival.

Despite the devastation of the early colonial era, the Taíno passed on their knowledge about their natural and cultural world to Europeans and Africans who arrived to the islands, and Native culture and people survive—and thrive—today. The Smithsonian’s Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project (CILP), co-led by Ranald Woodaman, Exhibitions and Public Programs Director at the Smithsonian Latino Center, and José Barreiro, Assistant Director for Research at the National Museum of the American Indian, explores how Taíno culture continues to evolve and thrive, despite the first devastating encounter with European colonization. The Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project tells this story of perseverance and helps provide a framework for understanding Taíno heritage in a multiethnic context.

The Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project tells this story of perseverance and helps provide a framework for understanding Taíno heritage in a multiethnic context.

José Barreiro (NMAI) visits the Taíno ceremonial site of Caguana. This well-known set of symbols is thought to connect the political and spiritual power of local chiefs with the authority of their ancestors. Photo Credit: Ranald Woodaman.

Through research and public programs, Smithsonian researchers are engaging with contemporary understandings of Taíno history and Native heritage. Much of this work is being done for audiences from the Caribbean region. According to Christina Gonzalez, a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin who has conducted research with CILP, “the project’s goal is to encourage people to rethink their own culture, history, and identity, and even engage in work to recover aspects of their culture.”

Many elements of popular Caribbean culture, particularly rural culture, derive from Native traditions. “Across the Caribbean, in Jamaica, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Haiti, you can find indigenous influences: herbal traditions, local spiritual or religious traditions, memories associated with the landscape, traditional agricultural crops and farming methods, home-building techniques, crafts like basketry and fishing nets, and Taíno words,” Ranald said. Many words today, especially in the Spanish Caribbean, reflect Taíno influence, including the names “Cuba,” “Haiti,” and everyday vocabulary like “barbeque,” “canoe,” and “hurricane.”

“Across the Caribbean, in Jamaica, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Haiti, you can find indigenous influences: herbal traditions, local spiritual or religious traditions, memories associated with the landscape, traditional agricultural crops and farming methods, home-building techniques, crafts like basketry and fishing nets, and Taíno words,” Ranald said. Many words today, especially in the Spanish Caribbean, reflect Taíno influence, including the names “Cuba,” “Haiti,” and everyday vocabulary like “barbeque,” “canoe,” and “hurricane.”

Candido Rojas Martínez discusses his process for making a cayuco, or small river canoe. Traditional methods for making canoes are adapting to the scarcity of local woods. Photo by Boynayel Mota.

Since the 1970s, new groups of Native-descendant people have come together to celebrate and revive Taíno heritage, challenging the dominant history of the region by reclaiming ancestral heritage and emphasizing the endurance of Native roots.

Alice Chéverez is part of a generation of Puerto Rican artisans who have revived Taíno crafts like pottery based on archaeological findings. Photo Credit: Ranald Woodaman.

Photo Credit: Ranald Woodaman.

CILP seeks to create a space for researching Native heritage post-1492 within a multilayered history of the Caribbean. This project is, “about exploring the science of survival; about looking at examples of resilience and agency and the ways in which Native people and their cultures may continue to survive and live despite belief in their disappearance and nonexistence,” Christina stated.

CILP began in 2010 with support from the Smithsonian Grand Challenges Consortia and is a collaboration between the Smithsonian Latino Center (SLC), the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) and its network of partner institutions and researchers in the Caribbean and the United States. These include the Museo del Hombre Dominicano—the main anthropology museum of the Dominican Republic. Smithsonian already had excellent yet rarely studied archaeological and ethnographic Caribbean collections, and expertise in documenting communities in Eastern Cuba from NMAI Assistant Director for Research José Barreiro. A multidisciplinary group of scholars, mostly from the Caribbean, worked with Ranald and José to review the Smithsonian’s Caribbean archaeological and anthropological collections. These workshops culminated in a public symposium at NMAI in 2011 on the survival of Taíno culture in contemporary Caribbean consciousness. The project now includes ethnographic research in local communities and local collections of Taíno artifacts.

A multidisciplinary group of scholars, mostly from the Caribbean, worked with Ranald and José to review the Smithsonian’s Caribbean archaeological and anthropological collections. These workshops culminated in a public symposium at NMAI in 2011 on the survival of Taíno culture in contemporary Caribbean consciousness. The project now includes ethnographic research in local communities and local collections of Taíno artifacts.

CILP organized its first interdisciplinary workshop in 2011. Here, (from left to right) Jose Barreiro, Osvaldo Garcia-Goyco, Juan Manuel Delgado Colón, Alejandro Hartmann, and Emily Skeels visit NMAI collections. Photo Credit: Ranald Woodaman.

Part of the ethnographic research for CILP involves fieldwork. Surveys gather first-person accounts of individual, family and community connections to indigenous identity and heritage, maintained by indigenous and non-indigenous practitioners. One of the project’s associated researchers, textile expert Soraya Serra Collazo, led Christina and other team members to a prime example of cultural continuity; for instance, one woman in her eighties in a rural area of Puerto Rico, one of the only people left who makes hammocks using the fibers from a plant called maguey. Christina noted, “This was believed to be a lost art… her practice shows it has survived.”

Christina noted, “This was believed to be a lost art… her practice shows it has survived.”

Ranald describes the CILP research methodology as “open source,” because all of their tools and process are made available to interviewees. This includes surveys to identify people, families, and communities who identify as Native descendants, which many local stakeholders use for their own research. The project also supports families in creating family trees. “This work explores how cultural life continues and we’re seeing that in living people whose stories are often silenced or whose experiences are not taken seriously in the production of history. It gives them a platform to share their voices,” Christina said.

The Moxum family have mixed Native roots. Mr. Norman Moxum is of Arawak-descent, and his wife, Yolanda Moxum, comes from a Miskito community in Honduras. Photo Credit: John Homiak.

One such platform is a website that is being conceived as a practical tool for understanding Native ancestry, especially DNA, as well as a general resource for those who want to learn more about Taíno culture. Christina described, “the hope is that it also advances the development of knowledge on the topic of Caribbean indigenous peoples and cultural traditions by offering scholars a database of information to further their own work, by empowering the public with the tools to conduct research on their own families and with their communities, and by igniting interest from future scholars in what is very much still a burgeoning area of study.”

Christina described, “the hope is that it also advances the development of knowledge on the topic of Caribbean indigenous peoples and cultural traditions by offering scholars a database of information to further their own work, by empowering the public with the tools to conduct research on their own families and with their communities, and by igniting interest from future scholars in what is very much still a burgeoning area of study.”

The project opened a 2018 exhibition at The National Museum of the American Indian in New York, NY. The exhibition will feature Smithsonian’s archaeological collections and CILP research findings. Before and after the exhibition development, the project also plans to expand its research into the fields of linguistics (in particular the study of place names), botany and ethnomedicine, and historical recovery work. Even after the exhibition closes, the research CILP has developed will continue to tell the story of the Taíno and expand our understanding of what it means to be Taíno today.

Learn more about: Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project

Meet our people: Ranald Woodaman, José Barreiro, Christina Gonzalez

The Taino People, a story

The Taino People, a story – African American Registry

Fri, 10.07.1492

The Taino People, a story

*The Taíno people are celebrated on this date in 1492. They are the indigenous people of all of the Caribbean that were the first to encounter white Europeans during the Middle Passage.

At the time of European contact in the late fifteenth century, they were the primary peoples of Cuba, Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic and Haiti), Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The Taíno were the first New World peoples to engage with Christopher Columbus. They speak the Taíno language, an Arawakan language.

Groups currently identify as Taíno, most notably among the Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Jamaicans, and Dominicans, both on the islands and the United States mainland. Some scholars, such as Jalil Sued Badillo, an ethnohistorian at the University of Puerto Rico, assert that although the official Spanish histories speak of the disappearance of the Taínos as an ethnic identification, many survivors left descendants usually by intermarrying with other ethnic groups.

Some scholars, such as Jalil Sued Badillo, an ethnohistorian at the University of Puerto Rico, assert that although the official Spanish histories speak of the disappearance of the Taínos as an ethnic identification, many survivors left descendants usually by intermarrying with other ethnic groups.

Recent research revealed a high percentage of mixed or tri-racial ancestry in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Those claiming Taíno ancestry also have Spanish ancestry, African ancestry, and often, both. The Spanish conquered various Taíno chiefdoms during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. According to The Black Legend and some contemporary scholars such as Andrés Reséndez, warfare and harsh enslavement by the colonists decimated the population. Men were forced to work on colonial plantations and gold mines; as a result, there was no Taíno left to cultivate their crops and feed their population.

Conversely, most scholars believe that European diseases caused the majority of deaths. A smallpox epidemic in Hispaniola in 1518–1519 killed almost 90% of the surviving Taíno. The remaining Taíno were intermarried with Europeans and Africans and were incorporated into the Spanish colonies. The Taíno were considered extinct at the end of the 18th century. However, since about 1840, there have been attempts to create a quasi-indigenous Taíno identity in rural areas of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. This movement accelerated among Puerto Rican communities in the mainland United States in the 1960s. At the 2010 U.S. census, 1,098 people in Puerto Rico identified themselves as “Puerto Rican Indian,” 1,410 identified as “Spanish American Indian,” and 9,399 identified as “Taíno.” In total, 35,856 Puerto Ricans considered themselves Native American.

A smallpox epidemic in Hispaniola in 1518–1519 killed almost 90% of the surviving Taíno. The remaining Taíno were intermarried with Europeans and Africans and were incorporated into the Spanish colonies. The Taíno were considered extinct at the end of the 18th century. However, since about 1840, there have been attempts to create a quasi-indigenous Taíno identity in rural areas of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. This movement accelerated among Puerto Rican communities in the mainland United States in the 1960s. At the 2010 U.S. census, 1,098 people in Puerto Rico identified themselves as “Puerto Rican Indian,” 1,410 identified as “Spanish American Indian,” and 9,399 identified as “Taíno.” In total, 35,856 Puerto Ricans considered themselves Native American.

Reference:

BHM.org.UK

Britannica.com

New Poem Each Day

When you feel blue, the best thing to do is tell yourself to forget it. Laugh your cares away Tomorrow’s another day And Everything will be Copasetic. Never look… The Copestedics Song by Charles Honi Coles and Paul Branker

Laugh your cares away Tomorrow’s another day And Everything will be Copasetic. Never look… The Copestedics Song by Charles Honi Coles and Paul Branker

Read More

Religions and languages in Puerto Rico

- Destination guide

- Cities and regions

- Vieques Island

- Ponce

- Attractions

- Culture: what to see

- Puerto Rico Festivals

- Active recreation

- Entertainment, nightlife

- Parks and landscapes

- Soul of Puerto Rico

- Kitchen and restaurants

- Traditions and coloring

- Festivals and holidays

- Languages and religions

- Leisure with children

- Shopping and shops

- Travel tips

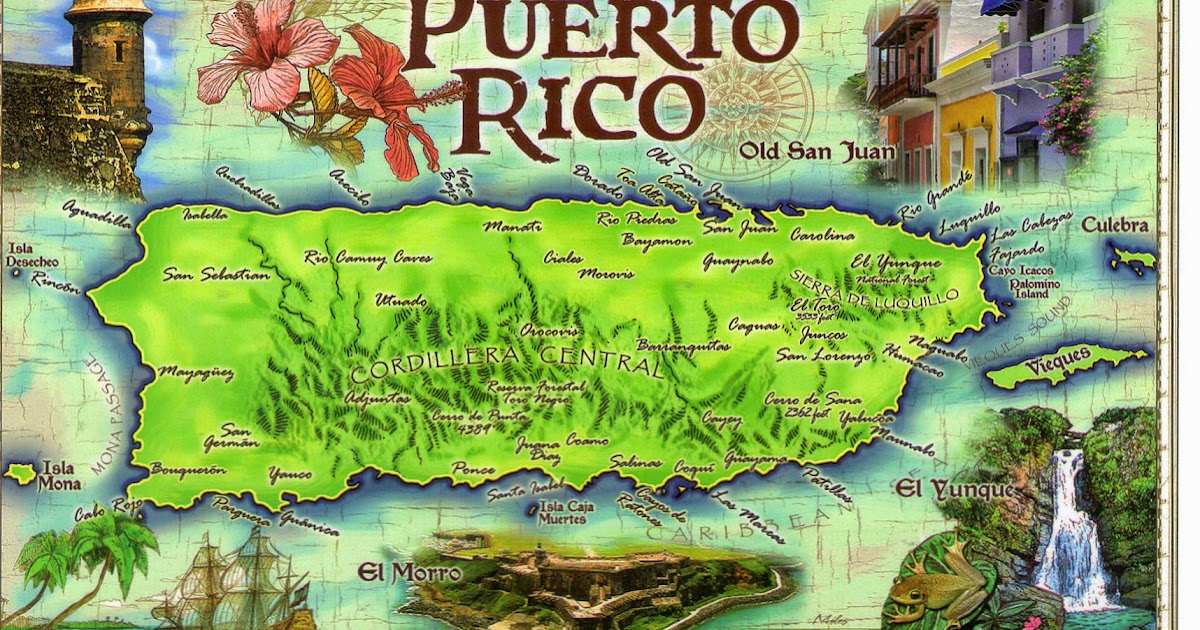

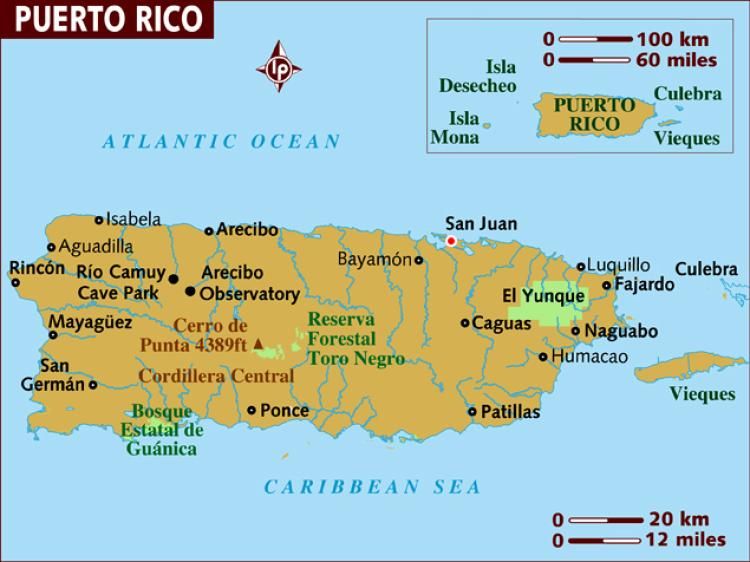

- Maps of Puerto Rico

- Printed cards

- Interactive map

- Useful info

- How to get around better

- Nature Puerto Rico

- When to visit – climate

- Languages and religions

- Political organization

- National economy

- Hotel reservations

- Car rental

Puerto Rico Hotels

Prior to the colonization by the Spaniards, Indians from the Arawak tribe lived in Puerto Rico. The language of communication here was one – Taino. As a result of the brutal treatment of the natives by the Spaniards and the inability of the latter to develop immunity to diseases imported from Europe, the Arawaks completely died out, and the Taino language went into oblivion with them. Instead, Spanish began to spread on the island. From 1508, planters began to massively exploit slaves brought from Africa. Thus, the remnants of Indians mixed with Africans and Spaniards, and the language began to form from the Taino, Spanish and African dialects.

The language of communication here was one – Taino. As a result of the brutal treatment of the natives by the Spaniards and the inability of the latter to develop immunity to diseases imported from Europe, the Arawaks completely died out, and the Taino language went into oblivion with them. Instead, Spanish began to spread on the island. From 1508, planters began to massively exploit slaves brought from Africa. Thus, the remnants of Indians mixed with Africans and Spaniards, and the language began to form from the Taino, Spanish and African dialects.

Puerto Rico is a wonderful place to travel with children. Fresh air, warm water, a lot of greenery and sun will benefit children, acquaintance with the unique …

Open

Since the colonizers spoke Spanish, it formed the basis of a language that developed from a mixture of existing dialects. In the 19th century, mass migration to our island of Germans, French, Irish and Portuguese began. These settlers, within their diasporas, spoke their native languages, but the process of mixing local Spanish with the languages of immigrants was inevitable. At the beginning of the 20th century, Puerto Rico came under the control of the United States of America. The power structure of our country has been reorganized. Legislative power passed to the Congress, in which the Americans played the main role. Therefore, from 1898 years on the island began to spread English.

These settlers, within their diasporas, spoke their native languages, but the process of mixing local Spanish with the languages of immigrants was inevitable. At the beginning of the 20th century, Puerto Rico came under the control of the United States of America. The power structure of our country has been reorganized. Legislative power passed to the Congress, in which the Americans played the main role. Therefore, from 1898 years on the island began to spread English.

In subsequent years, the inhabitants of our country began to leave to work in the United States, and those who returned continued to speak English. Now there is a confrontation between political forces, and for this reason there is uncertainty with the state language. The Americans failed to translate the communication of our residents into English. Moreover, in 1991, the governor of Puerto Rico issued a decree according to which Spanish acquired the status of the only official language. Copyright www.orangesmile.com

Copyright www.orangesmile.com

Shopping in Puerto Rico can be a real discovery and adventure if approached wisely. Useful, unique and interesting products can be found in …

Open

But political forces seeking to annex the island to America as a full-fledged state managed to prove the illegality of such a decree and in 1993 were able to achieve the recognition of English as the state language along with Spanish. U.S. District Court proceedings for Puerto Rico are now conducted in English, and Spanish is the official language of the island’s authorities. As of 2015, for 94% of the inhabitants of our country this language was native, and 78% understand English. 6% speak only English.

The religion of our island, which the first Europeans encountered, was that of the Taíno Indians. The indigenous people honored any form of life, bowed to the dead ancestors and other spirits, who were called “seven”. They were hewn out of stones and given the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, and sometimes a man. During religious rituals, it was customary for the Taíno to induce vomiting with small sticks that they swallowed. According to the beliefs of the Indians, the ritual cleansed the body and soul of impurities. Before eating, bread was offered first of all to the spirits of the seven, then to the shaman, then to everyone else. After that, an epic song was played, accompanied by the playing of musical instruments.

They were hewn out of stones and given the appearance of toads, turtles, snakes, and sometimes a man. During religious rituals, it was customary for the Taíno to induce vomiting with small sticks that they swallowed. According to the beliefs of the Indians, the ritual cleansed the body and soul of impurities. Before eating, bread was offered first of all to the spirits of the seven, then to the shaman, then to everyone else. After that, an epic song was played, accompanied by the playing of musical instruments.

Most Puerto Ricans are Catholics, so Christmas on the island is celebrated in December. Catholic masses are held from 15 to 24 December, that is, until …

Open

The supreme deity was “yukaha” – white yuka or the spirit of yuki. In the concept of the Taino, she was a source of food, therefore, she demanded reverence. In addition, the local Indians believed in the realm of the dead, where the souls of the dead go. During the daytime, everyone has a rest there, and at night all the souls turn into bats and eat guava fruits. The eradication of these beliefs and rituals began with the colonization of the island by the Spaniards. In 1511, the first Catholic diocese was founded on the territory of our country. In the next six years, Bishop Alonso Manso arrived. He was also appointed inquisitor to suppress heresy and burn dissidents at the stake. Local Indians began to be involved in the construction of temples. Among the missionaries there were those who were kind to the natives. In 1521, by order of the Spanish king, the construction of the central temple began.

The eradication of these beliefs and rituals began with the colonization of the island by the Spaniards. In 1511, the first Catholic diocese was founded on the territory of our country. In the next six years, Bishop Alonso Manso arrived. He was also appointed inquisitor to suppress heresy and burn dissidents at the stake. Local Indians began to be involved in the construction of temples. Among the missionaries there were those who were kind to the natives. In 1521, by order of the Spanish king, the construction of the central temple began.

Until the end of the 16th century, all the dioceses of the small islands were included in the Puerto Rican church, but in our time only the islands of Vieques and Culebra remained subordinate. In the period from 1833 to 1846, the Catholic elite had to leave the island, and the church property went to the governors of the municipalities and was secularized. Five years later, Spain signed a concordat with the Vatican, and the Catholic Church of our country regained part of the property. In 1960, an independent Puerto Rican ecclesiastical province was formed. The dioceses of the island became its suffragans. Together with the Catholics, Muslims also penetrated here in the Middle Ages, but their religion did not gain such a powerful influence as the Catholic one.

In 1960, an independent Puerto Rican ecclesiastical province was formed. The dioceses of the island became its suffragans. Together with the Catholics, Muslims also penetrated here in the Middle Ages, but their religion did not gain such a powerful influence as the Catholic one.

The magnificent nature of the island of Puerto Rico can enchant any seasoned traveler. Fresh air, crystal clear emerald waters, …

Open

The first ministers of Islam were Iberians and came to the island along with seafarers. They came here in violation of Spanish laws that forbade them to emigrate to America. Among them were merchants, travelers and slaves. In addition to the Iberians, there were Muslim slaves from Africa. But their communities could not survive under the brutal suppression of culture and religion. Years later they were converted to Catholicism or African American cults. For this reason, the spread of Islam in our country has weakened, and today’s Muslims are not spiritually connected in any way with the ancient Muslim settlers. In our time, ministers of Islam began to come to us in the middle of the 20th century from Palestine. At 19In 70, the number of Muslim settlers was 2,000 and has been steadily increasing ever since. In 1981, our first mosque was built.

In our time, ministers of Islam began to come to us in the middle of the 20th century from Palestine. At 19In 70, the number of Muslim settlers was 2,000 and has been steadily increasing ever since. In 1981, our first mosque was built.

This article about religion and languages in Puerto Rico is protected by the copyright law. Its use is encouraged, but only if the source is indicated with a direct link to www.orangesmile.com.

Puerto Rico – guide chapters

one

2

3

four

5

6

7

eight

9ten

eleven

12

13

14

fifteen

Country maps

Cars on OrangeSmile

Lexington hotel welcomes guests with indoor plants

All travelers who use the new service and check into the hotel with their plants will be in for a pleasant surprise. They will receive a beautiful live plant in a pot, which will be a pleasant reminder of the comfort and coziness of a Lexington boutique hotel. The upscale Elwood Hotel & Suites occupies one of the city’s historic buildings. This architectural monument is very popular with tourists. The snow-white facade of the building is decorated with a bright painting depicting flowers.

The upscale Elwood Hotel & Suites occupies one of the city’s historic buildings. This architectural monument is very popular with tourists. The snow-white facade of the building is decorated with a bright painting depicting flowers.

Read

Photogallery of iconic places of Puerto Rico

Color and traditions in the regions of Puerto Rico

Ponce

For the holiday, locals make bright papier-mâché masks; such masks look quite intimidating. They are called “vejigante”, the locals borrowed the image for creating such masks from local mythology. The program of the traditional carnival in Ponce is very intense and is considered one of the most interesting in the country. It includes performances by folk groups and musicians, special entertainment for children, as well as numerous gastronomic programs. … Read

Puerto Rico: traditions in the regions

OrangeSmile. com is a provider of convenient and reliable online car and hotel booking solutions. We offer over 15,000 destinations with 25,000 rental locations and 500,000 hotels worldwide.

com is a provider of convenient and reliable online car and hotel booking solutions. We offer over 15,000 destinations with 25,000 rental locations and 500,000 hotels worldwide.

Secure connection

Head office

Weegschaalstraat 3, Eindhoven

5632 CW, The Netherlands

+31 40 40 150 44

User agreement (Terms of Service) |

Privacy Policy |

About company

Copyright © 2002 –

OrangeSmile Tours B.V. | OrangeSmile.com | Under the control of IVRA Holding B.V. – Registered with the Netherlands Chamber of Commerce: Kamer van Koophandel (KvK), The Netherlands No. 17237018

Arawaks | it’s… What is the Arawaki?

This term has other meanings, see Arawaki (meanings).

Arawak Girl Archer (Artist John G. Stedman)

Arawak settlement.

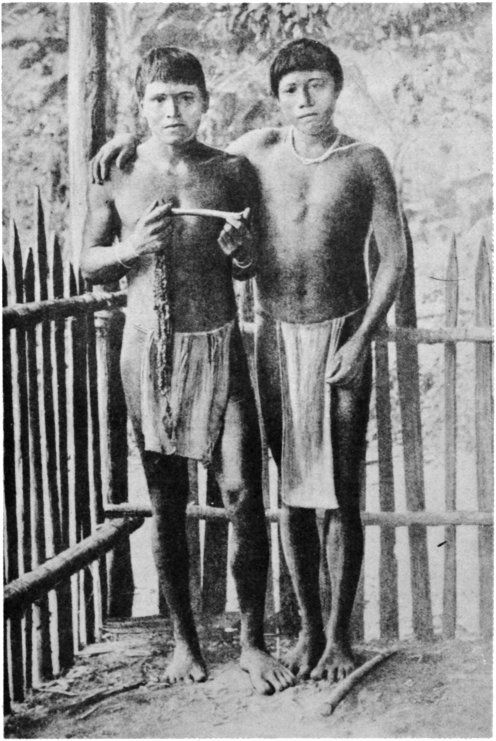

Arawaks from the Guana tribe. Artist Hercule Florence.

Artist Hercule Florence.

Arawaks – a group of Indian peoples in South America, with a total number of 400 thousand people (2000), half of them are guajiro. They speak Arawakan languages.

Contents

|

Ethnic composition and settlement

Linguistically they are divided into northern and southern subfamilies.

Northern Arawaks includes:

- the Amazonian branch, present in the Llanos, in the northwestern and central Amazon: piapoco, achagua, yucuna, curripaco, catapolitani, warikena, tariana, baniva, bare, extinct, maipureo, yavitero etc.

- Caribbean branch – Guajiro in Colombia and Venezuela, Vapishana, Lokono (actually Arawaks) in Suriname, Guyana, Guyana, extinct Taino in the Greater Antilles and Lucayans in the Bahamas.

In terms of language, this also includes the “Caribs” of the Lesser Antilles (derived from a mixture of alien male Caribs and local Arawakan Inyeri women) and related caribuna, or “black Caribs”, in the colon. period spread to the coast of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua. A special position is occupied by the Palikur language in French Guiana and adjacent regions of Brazil.

In terms of language, this also includes the “Caribs” of the Lesser Antilles (derived from a mixture of alien male Caribs and local Arawakan Inyeri women) and related caribuna, or “black Caribs”, in the colon. period spread to the coast of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua. A special position is occupied by the Palikur language in French Guiana and adjacent regions of Brazil.

The southern subfamily includes the Arawaks of Peruvian Montagna (Amuesha, Chamicuro, Piro, Ipuriná, Campa, or Asháninka and the closely related Machigenga), Eastern Bolivia (Moho and Baure), Mato Grosso (Paresi, Tereno, Arawak groups from among the Xinguano , including waura, mekhinaku, yaulapiti). Small groups of Tereno are settled in Paraguay and Argentina.

History

The settlement of the Arawaks took place approximately from the end of the 2nd millennium BC. e. from the savannas of the Orinoco Basin (archaeol. traditions of the Barrancas and Saladero, collectively known as “saladoid culture”) in connection with the transition to more developed agriculture – the cultivation of bitter cassava. The advance of A. to Guiana and the Antilles (from the end of the 1st millennium BC), to Montaña (the hupa-ia complex of the beginning of the 1st millennium AD), and eastern Bolivia (Chane, 7th century AD) are being reconstructed. .), upper Xingu (10th century AD).

The advance of A. to Guiana and the Antilles (from the end of the 1st millennium BC), to Montaña (the hupa-ia complex of the beginning of the 1st millennium AD), and eastern Bolivia (Chane, 7th century AD) are being reconstructed. .), upper Xingu (10th century AD).

Economy and culture

Arawaks belong to the type of culture of the South American rainforest Indians. Traditional occupation – manual slash-and-burn agriculture. The main crop is bitter cassava, the preparation of which is associated with a complex of specialties. tools – large graters, wicker bags for squeezing poisonous juice, large braziers.

Among the Arawaks of Haiti and Puerto Rico, to a lesser extent Cuba, the Venezuelan coast, the lower, middle Orinoco and eastern Bolivia, an institution of hereditary leaders, a professional priesthood, was formed; there were settlements with a population of over 1 thousand people. Characteristic of many Arawaks, large wind musical instruments were used in male rituals.

Northwest The Amazonian Arawaks entered into close interaction with the eastern Tukano, in the upper Xingu – with the Caribs, Tupi and Trumai. In both cases, elements of the Arawak culture dominated. In the south of Mato Grosso, close to Tereno Chane in the 17-18 centuries. were subordinate to the mbaya horse hunters and became part of the modern kaduveo (kadiuveo).

Literature

- Arawaks // Great Russian Encyclopedia. Volume 2, M., 2005.

- Berezkin Yu. E. Bridge across the ocean. New York, 2001;

- Lathrap D.W., The Upper Amazon, N.Y.—Wash., 1970;

- Sanoja M., Vargas I., New light on the prehistory of Eastern Venezuela // Advances in world archeology, v. 2, N.Y.—[a.o.], 1983, p. 205-44.

- Arkady Fidler. “White Jaguar – Chief of the Arawaks”

See also

- Arawaks (people)

Links

- Arowaki // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: In 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional).

In terms of language, this also includes the “Caribs” of the Lesser Antilles (derived from a mixture of alien male Caribs and local Arawakan Inyeri women) and related caribuna, or “black Caribs”, in the colon. period spread to the coast of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua. A special position is occupied by the Palikur language in French Guiana and adjacent regions of Brazil.

In terms of language, this also includes the “Caribs” of the Lesser Antilles (derived from a mixture of alien male Caribs and local Arawakan Inyeri women) and related caribuna, or “black Caribs”, in the colon. period spread to the coast of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua. A special position is occupied by the Palikur language in French Guiana and adjacent regions of Brazil.