Chinchorro puerto rico: The Lure of Puerto Rico’s Chinchorros | Travel

The Lure of Puerto Rico’s Chinchorros | Travel

Laura Kiniry

Travel Correspondent

The sweet and smoky scents of grilled meat and fried cornmeal rise up from the streets of Piñones, a beachfront neighborhood in the Puerto Rican town of Loíza. This area of mangrove swamps and Afro-Caribbean culture is a hotbed of chinchorros: dozens of simple kiosks and food stalls—often one next to the other—serving up some of the island’s most indulgent edible samplings. We’re talking enormous plates of pork, rice and pigeon peas; skewered kebabs of beef and chicken; and loads of deliciously fried fritters, including meat-filled alcapurrias, cheese-stuffed sorullos and breadcrumb-coated croquetas de jamón y queso. Of course, at a chinchorro, cheap beer and mixed drinks are also on the menu.

“There’s nothing that’s supposed to be fancy about a chinchorro,” says Stephen Santiago, a Puerto Rican native and culinary host with local walking tour company, Flavors Food Tours—San Juan. “Think of them like a Texas roadhouse or a Louisiana clambake.” These rustic and down-to-earth eateries, which range from flat-out watering holes to basic restaurants, aren’t limited to Piñones, either. In fact, they exist island-wide, from the Guavate or “Pork Highway” section of mountainous Cayey, in central Puerto Rico (where they’re said to have first originated), to the coastal town of Luquillo, tucked between Atlantic waters and tropical El Yunque National Rainforest. Although no one really knows when they began, many Puerto Ricans will tell you that they remember visiting chinchorros when they were younger, in the company of their parents, cousins, aunts and uncles. However, it’s the chinchorrear, or the act of hopping between multiple chinchorros to eat, drink and dance, that’s more recently become an essential part of Puerto Rican culture. The tradition seems to have truly come into its own just in the last decade or two.

“Think of them like a Texas roadhouse or a Louisiana clambake.” These rustic and down-to-earth eateries, which range from flat-out watering holes to basic restaurants, aren’t limited to Piñones, either. In fact, they exist island-wide, from the Guavate or “Pork Highway” section of mountainous Cayey, in central Puerto Rico (where they’re said to have first originated), to the coastal town of Luquillo, tucked between Atlantic waters and tropical El Yunque National Rainforest. Although no one really knows when they began, many Puerto Ricans will tell you that they remember visiting chinchorros when they were younger, in the company of their parents, cousins, aunts and uncles. However, it’s the chinchorrear, or the act of hopping between multiple chinchorros to eat, drink and dance, that’s more recently become an essential part of Puerto Rican culture. The tradition seems to have truly come into its own just in the last decade or two.

“It’s a practice that’s always existed,” says Angel L. Toledo, founder of Puerto Rico’s Chinchorreo Bus, which has been running private and public bus tours to groups of chinchorros across the island since 2011. “For a long time it just didn’t have a name.” Think of the chinchorrear as a food- and booze-fueled road trip that Puerto Ricans and tourists take part in together. “Not having to worry about drinking and driving,” says Toledo, or navigating Puerto Rico’s narrow two-lane roads, “is a big part of our bus tours.”

Toledo, founder of Puerto Rico’s Chinchorreo Bus, which has been running private and public bus tours to groups of chinchorros across the island since 2011. “For a long time it just didn’t have a name.” Think of the chinchorrear as a food- and booze-fueled road trip that Puerto Ricans and tourists take part in together. “Not having to worry about drinking and driving,” says Toledo, or navigating Puerto Rico’s narrow two-lane roads, “is a big part of our bus tours.”

El Velorio in Peñuelas, Puerto Rico

Discover Puerto Rico

While chinchorros have long been a part of the Puerto Rican fabric (especially in the island’s central mountain region), Leslie Padro, founder of Flavors Food Tours—San Juan, believes they became more prevalent across the island during the mid-to-late-20th century. First, with the shifting of local demographics, as industrialization took over the island’s sugar monoculture, and Puerto Rico’s city-dwellers migrated to the U.S., while those in its rural areas relocated to the towns and cities. Soon after, “Caribbean tourism blossomed,” says Padro. “I think these kiosks were not only a nod to visitors, but also a good side hustle.”

Soon after, “Caribbean tourism blossomed,” says Padro. “I think these kiosks were not only a nod to visitors, but also a good side hustle.”

Still, the communal, party-like gatherings of chinchorrear are a direct result of Puerto Rico’s close-knit culture, insists Padro. “The people here are very community driven,” she says, “and families will even bring their kids along with them during the day. Nobody minds that they’re loud, since Puerto Rico as a whole is a bit loud anyway.” Many chinchorros will have live bands playing, and there are people dancing salsa and merengue. At times, there’s even karaoke.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Flavors Food Tours (@flavorsfoodtours)

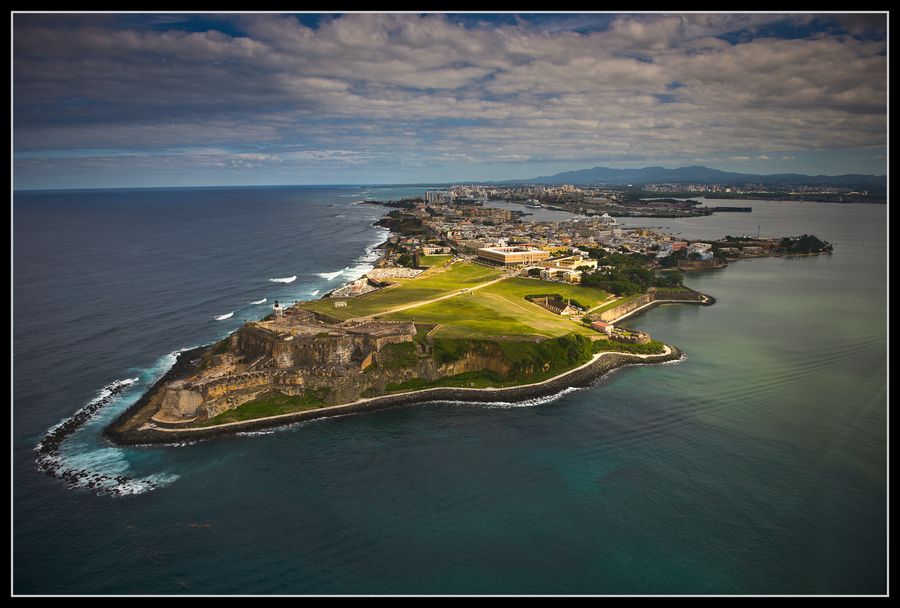

This casual simplicity is decidedly one of the chinchorros’ biggest draws, which is why you won’t see many of them in Old San Juan, a historic center with a more upscale vibe. In Puerto Rican neighborhoods like Piñones, some chinchorros don’t even have signs identifying them. Others cook their food over makeshift grills made from repurposed oil drums, which have been cut in half and fired up with scrap wood. Many chinchorros are open-air, “so there’s a good chance you’re going to get bit by mosquitos,” says Santiago. “But if you want an ice-cold beer for less than $5 USD, these are the places to go.”

In Puerto Rican neighborhoods like Piñones, some chinchorros don’t even have signs identifying them. Others cook their food over makeshift grills made from repurposed oil drums, which have been cut in half and fired up with scrap wood. Many chinchorros are open-air, “so there’s a good chance you’re going to get bit by mosquitos,” says Santiago. “But if you want an ice-cold beer for less than $5 USD, these are the places to go.”

Sometimes, a chinchorro will feature a glass and metal display case showcasing various fritters, although both Padro and Santiago agree that the best chinchorros make their fritters fresh to order. Natural fruit juices are another part of the offerings. “Sometimes they’ll even squeeze the fruits right in front of you,” says Toledo. “Oranges, limes, grapefruit…passion fruit is particularly popular.” The place will then add alcohol to the mix. “Otherwise it wouldn’t be a chinchorro,” he says. “Trust me.”

Kiosko El Boricua in Piñones

Discover Puerto Rico

Toledo designed the first public tour for Chinchorreo Bus with local Puerto Rican residents in mind, but it immediately attracted its fair share of tourists. He quickly realized he was on to something. Today Chinchorreo Bus offers both private and public bus tours along 14 different chinchorrear routes across the island, including various coastal and mountain regions. Although their public tours currently take place once a month, private tours are available anytime, with add-ons ranging from a full lunch to an onboard DJ.

He quickly realized he was on to something. Today Chinchorreo Bus offers both private and public bus tours along 14 different chinchorrear routes across the island, including various coastal and mountain regions. Although their public tours currently take place once a month, private tours are available anytime, with add-ons ranging from a full lunch to an onboard DJ.

Typically, Chinchorreo Bus public tours last about eight hours and include three-to-four stops, with prices ranging from between $25 to $50 USD. “It all depends on how far the places are from each other,” says Toledo, “as well as what they offer.” For example, while the average stay at a stop is one hour, “If there is live music we may even stay longer,” he says, “and possibly leave it for the end and have dinner there.” With a private tour, you can decide for yourself how long you’d like to stay. “Whether it’s 15 minutes or three hours,” says Toledo. “You’re in charge.”

instagram.com/p/CTwhAX5rT6Z/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading” data-instgrm-version=”14″>

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Flavors Food Tours (@flavorsfoodtours)

Some tour companies, like Puerto Rico-based Bespoke Lifestyle Management, which specializes in transport and concierge services, will help organize outdoor activities and chinchorrear pairings. For example, a morning visit to one of Puerto Rico’s natural swimming holes, like Patillas’ Charco Azul (Blue Pool), coupled with an afternoon of chinchorro-hopping along the town of Guardarraya’s palm-laden coastline.

But while many people are just happy drinking and eating from place-to-place, others have their favorites, whether it’s one of the many chinchorros along La Ruta de la Longaniza in the central mountains, where fried empanadillas (beef turnovers) and rellenos (stuffed potatoes) incorporate ingredients from local farms, or Kiosko El Boricua, a famed Piñones chinchorro known for its made-to-order fritters and heaping-sized portions. Whatever the case, the experience is sure to be quintessentially Puerto Rican.

Whatever the case, the experience is sure to be quintessentially Puerto Rican.

“You’re going there for Puerto Rican food, and Puerto Rican culture,” says Padro. “It’s just a great way to connect.”

Recommended Videos

How Puerto Rico’s Chinchorro Food Stalls Are Preserving the Island’s Culinary Roots

Still owned by the Ortiz family, La Sombra offers a feel of what a chinchorro represents for local customers—a community gathering place with great food. On any given day, La Sombra is full of locals like Hector G. (who declined to share his full last name), who has been going there for 15 years. “The food is amazing, just like how I remember it from years ago,” he says. “ I come here every week to meet my friends, eat, and socialize.”

For Aracelys Ortiz and her siblings, the grandchildren of Doña Maria, managing the business is akin to taking care of family—from the people who work there, to the regular customers who frequent the restaurant. “From our bakery to our four kitchens, we provide support to many of the locals,” she says. “Even in difficult economic times we offer employment within our community. And that means so much more than just being a restaurant owner.”

“From our bakery to our four kitchens, we provide support to many of the locals,” she says. “Even in difficult economic times we offer employment within our community. And that means so much more than just being a restaurant owner.”

Many chinchorros along the Ruta de la Longaniza support local farms by sourcing ingredients nearby, ensuring economic resources remain within the community. La Sombra even has their own farm in Orocovis where they grow seasonal produce that makes its way into their kitchen and signature dishes.

But this concept of food enterprises as centers of social and economic sustainability also extends to the coast, where the island’s fishing community is. Olmeda remembers her favorite chinchorro in Fajardo, where she would go with her grandparents growing up, and the role it played in the seaside community. “[El Racar Sea Food] has been there for over 30 years,” she says. “It is no more than a shack by the water but it has such special memories for me. ”

”

Being close to the tourist-attracting bioluminescent bay, El Racar Sea Food is ever-popular with locals and tourists. They even have a hook and cook option, which supports fishing charters in Fajardo. “The owners are very involved in the community by sourcing from local fishermen and helping promote tourism in the area,” says Olmeda. “In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the chinchorro was open and serving the community right from the get-go.”

While not a traditional chinchorro, Princesa in Old San Juan is proof that the cuisine they serve continues to have a place in newer establishments. Princesa’s mantra of ‘Tasting Puerto Rico’s history’ is executed by seeking inspiration from six different cookbooks dating from 1859 to 1950.

“Over the years the food scene has evolved with many outside influences of ingredients and techniques,” says Jan Daniel Diaz, one of the owners, “but we want to bring back that old world flavor by going back to the roots, and making people fall in love with the true essence of Puerto Rican cuisine. ” Some of the crowd favorites include creole muffins, beef medallions with yam, and plantain tostones. They, too, have a farm outside San Juan that provides fresh and locally grown ingredients for their dishes.

” Some of the crowd favorites include creole muffins, beef medallions with yam, and plantain tostones. They, too, have a farm outside San Juan that provides fresh and locally grown ingredients for their dishes.

“For us Puerto Ricans, food isn’t just to eat,” says Ricardo Ojeda, a history teacher and food tour guide at Flavors Food Tours. The many roles chinchorros play, from preserving the first longaniza recipe to creating space for local enterprise, are proof.

90,000 flight through time and space. North America. South America

Puerto Moorin. Ancient America: flight through time and space. North America. South America

WikiReading

Ancient America: flight through time and space. North America. South America

Ershova Galina Gavrilovna

Contents

Puerto Moorin

This culture existed in the Viru valley on the northern coast from the beginning of our era to 500. Not much is known about her – mainly what the burials preserved.

Not much is known about her – mainly what the burials preserved.

The dead were buried in soil pits about 1.5 m long and about 0.5 m wide. The dead were laid on their backs, with their heads to the south, which indicates a certain archaic layer of local traditions and religious ideas. The arms were extended along the body. Traces of deformation have been preserved on the skulls – flattening of the occiput. The body was most often wrapped in mats and fabrics tied with ropes.

The accompanying inventory was quite poor – only two or three vessels, standing at the shoulders or at the feet. They apparently contained food, as in two cases, corn cobs and peanut shells were inside.

In one of the burials there was an adult man laid with his head to the east. It must be said that only two burials with a similar orientation were found.

The face of the deceased was covered with a gourd bowl. On the right side of the body lay a staff, at the left shoulder – a gourd vessel, at the right – a ceramic one.

This text is an introductory fragment.

Puerto Rico Attack

Attack of Puerto Rico

In the early morning of September 24, 1625, lookouts stationed in the bastion of San Felipe del Morro, located in the Puerto Rican fortress of San Juan, saw an endless string of sails going towards Boqueron Bay. Ships anchored three miles from

Assault by Henry Morgan’s detachment of the forts of Puerto Bello

Assault by Henry Morgan’s detachment of the forts of Puerto Bello

In June 1668, the “general” of the filibusters of Jamaica, Henry Morgan, having only 460 people under his command, decided to attack one of the most fortified port cities of the Isthmus of Panama – Puerto Bello. This city,

This city,

John Coxon’s attack on Puerto Bello

John Coxon’s attack on Puerto Bello

Despite the fact that in 1668 Puerto Bello was thoroughly ravaged by filibusters under the command of Henry Morgan, the Spaniards managed to rebuild the city from the ruins, and they continued to use its harbor as a parking lot

Capture of Puerto Principe 9 by Morgan’s Detachment0026

Capture of Puerto Principe by Morgan’s detachment

Henry Morgan became the “general” of the filibusters of Jamaica shortly after their former leader, Edward Mansfelt, was captured by the Spaniards and was executed by them in Cuba. Morgan’s first operation as commander-in-chief was the audacious

[Discovery of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico]

[Discovery of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico]

On the first Sunday after All Saints’ Day, that is, on the third day of November, shortly before dawn, the helmsman of the flagship proclaimed: “Congratulations to everyone! The land is visible! Great was the joy expressed by all the people, and

[Discovery of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico]

[Discovery of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico]

On Sunday, November 3, when dawn broke, the whole flotilla saw land. And so great was the universal joy, as if the heavens had opened before the sailors; this land was an island, which the admiral called Dominica, because

And so great was the universal joy, as if the heavens had opened before the sailors; this land was an island, which the admiral called Dominica, because

Chapter 22 Henry Morgan’s attack on the city of Puerto Principe

Chapter 22

After the mysterious disappearance of Edward Mansfelt, the filibusters of Jamaica did not have a generally recognized leader for a long time, until at a general meeting of the crews of pirate ships based in Port Royal, the new “general”

Chapter 23. Morgan’s stunning trip to Puerto Bello

Chapter 23

In June 1668, the commander of the Jamaican flotilla, having only 460 people under his command, decided to attack the city of Puerto Bello. From the report of Morgan himself, it is known that nine leaders participated in this campaign

Atacama Desert – interesting facts | America

Locals believe that this place in the lifeless Atacama desert is indicated from above: it was here that a source of fresh water made its way out of the ground, and not the usual salty one, as it is for tens of kilometers around. However, there are enough wonders in the town of San Pedro de Atacama, the most extreme in Chile.

However, there are enough wonders in the town of San Pedro de Atacama, the most extreme in Chile.

There is no dry land!

Why did people settle here at all? In San Pedro de Atacama, no more than 10 mm of precipitation falls per year. That is, they are practically non-existent! Of the agricultural plants, only chili pepper is popular: it requires minimal watering, but it is considered unique – due to the dryness of the climate, it becomes more acute.

In addition to the fact that a freshwater stream miraculously appears from the ground, it just as suddenly goes into it literally after a few kilometers. But this is enough: San Pedro is the only oasis in the driest place on the planet – in the Atacama Desert, located in northern Chile on an area of 105 square meters. km.

More than 1000 km from the capital of Santiago, 240 km from the regional center of Antofagasta. However, despite the remoteness, a small town with a population of 5,500 people annually visit over 100,000 tourists. For comparison: if we count per capita, then 12 times more of them arrive in San Pedro de Atacama than in St. Petersburg!

For comparison: if we count per capita, then 12 times more of them arrive in San Pedro de Atacama than in St. Petersburg!

What is it that attracts a very hot and, moreover, alpine (2,407 m above sea level) city? First, a story that does not begin with the period of conquest by the Spaniards. Initially, there was a transshipment base of the Inca Empire on the famous road to the Pacific Ocean. The oasis, in fact, provided the only opportunity to make a long stop and rest. For security purposes, in the 12th century, a powerful fortress, Pucara de Quitor, was built on a nearby hill. Until now, its dilapidated walls and watchtowers, storage facilities have been preserved. Rumor has it that on quiet nights you can even hear the steps and whispers of the Incas, who died in an unequal battle with the invaders-conquistadors…

By the way, the name San Pedro is in honor of one of these conquerors, Pedro de Valdivia. Although the official founding date is 1450, Valdivia was born nearly half a century later. Only the old house where the Spaniard stayed and the perfectly preserved Catholic church, built in 1557, reminds of that colonial era. Everything is the same under a thatched clay roof and with the faces of saints, in many ways similar to the faces of local residents. The church was destroyed more than once by earthquakes, but each time it was restored, considering this place sacred: it was here that the first divine service in the vast expanses of Atacama took place in the presence of all the Indian tribes who arrived on it.

Only the old house where the Spaniard stayed and the perfectly preserved Catholic church, built in 1557, reminds of that colonial era. Everything is the same under a thatched clay roof and with the faces of saints, in many ways similar to the faces of local residents. The church was destroyed more than once by earthquakes, but each time it was restored, considering this place sacred: it was here that the first divine service in the vast expanses of Atacama took place in the presence of all the Indian tribes who arrived on it.

9000 years ago

Local residents traditionally believe that the souls of their ancestors help them overcome natural and other disasters. Not the modern aboriginal atakamenos, but much more ancient tribes of the Chinchorro Indians. Initially, they were nomads, but then they settled down and became famous for being the first in the world to use the ritual mummification of the dead. The oldest Chinchorro mummies found are over 9,000 years old, but the much more famous Egyptian mummies are about 4,000. Again, if only pharaohs and privileged dignitaries were embalmed in Egypt, then among the Indians – all the dead, including newborns. Surprisingly, such a venerable age of the Chinchorro mummies had almost no effect on their safety – the dry climate of the Atacama helped. Moreover, the earth makes it easier for archaeologists to search: it constantly brings mummies to the surface – more than 2000 of them have already been found.

Again, if only pharaohs and privileged dignitaries were embalmed in Egypt, then among the Indians – all the dead, including newborns. Surprisingly, such a venerable age of the Chinchorro mummies had almost no effect on their safety – the dry climate of the Atacama helped. Moreover, the earth makes it easier for archaeologists to search: it constantly brings mummies to the surface – more than 2000 of them have already been found.

One of the most ancient mummies was found near San Pedro de Atacama and is stored in the Archaeological Museum. Gustavo Le Page: It is named after a Belgian Jesuit monk who lived here from 1955-1980. It was thanks to his efforts that a building appeared next to the church, which contains the richest collection of ethnographic exhibits. After Le Page’s death, the Chinchorro mummy was displayed for a while in the exhibition hall to attract tourists, but things, on the contrary, went from bad to worse. Outraged residents demanded to remove it to the vault so as not to disturb the spirit of their ancestors. And so they did. However, even without the famous mummy out of 380,000 artifacts, there was something to choose for the exhibition.

And so they did. However, even without the famous mummy out of 380,000 artifacts, there was something to choose for the exhibition.

The microbe won’t survive!

Continuing the mystical theme, one cannot fail to mention the Valley of Death. It is quite possible to reach it from San Pedro de Atacama even on foot or by bicycle – only 4 km. Why such a gloomy name? Initially, because not a single daredevil who tried to cross it returned back. Later, scientists found out that in Death Valley there are not only living organisms, not even microbes! This is an eerie beauty that captivates with colors, especially at sunset. Strange sounds are heard here, supposedly the dead wanderers are asking for help. True, later researchers found a scientific explanation for this phenomenon – this is how salt crystallizes with a temperature difference.

The geothermal valley of El Tatio, located near San Pedro de Atacama, is also associated with the spirits of ancestors. It is no coincidence that the name is translated from the language of the Atakamen as “crying grandfather”. Third in the world after Yellowstone National Park in the USA and the Valley of Geysers in Russia in Kamchatka, it includes about 80 hot springs. This is again the highest source of geothermal waters – 4300 m above sea level. It is believed that while the “Crying Grandfather” pours his tears through the geysers, the life of the Atakamen will continue and they will not face troubles. How can one not recall the Onkilons from the science fiction novel “Sannikov Land” by Vladimir Obruchev!

Third in the world after Yellowstone National Park in the USA and the Valley of Geysers in Russia in Kamchatka, it includes about 80 hot springs. This is again the highest source of geothermal waters – 4300 m above sea level. It is believed that while the “Crying Grandfather” pours his tears through the geysers, the life of the Atakamen will continue and they will not face troubles. How can one not recall the Onkilons from the science fiction novel “Sannikov Land” by Vladimir Obruchev!

Gemini of the Moon and Mars

In San Pedro de Atacama, centuries-old history miraculously echoes modernity – space exploration. The very vast Universe that ancient people worshiped and that they continue to storm in the 21st century, what are we talking about?

16 km from the city is the Moon Valley with a length of 14 km. Where does this name come from? The similarity of the Moon Valley with the landscape of the star closest to us is almost like that of twin brothers. On this once seabed, the space between two ridges, under the influence of winds, was fancifully decorated with sand dunes, salt fields and low cliffs. Is that the color of all this silent and uninhabited splendor of a reddish hue, here associations with Mars involuntarily come. But at twilight or at night in the light of the moon, this is the moon’s surface!

Is that the color of all this silent and uninhabited splendor of a reddish hue, here associations with Mars involuntarily come. But at twilight or at night in the light of the moon, this is the moon’s surface!

Locals claim that this corner of the Atacama served as a training ground for the American astronauts who landed on the moon. In any case, when in San Pedro in July 1969 they saw pictures from the Apollo 11 spacecraft, they were surprised at the similarity with their native valley.

16 km from the city is the Moon Valley with a length of 14 km. The similarity of the Moon Valley with the landscape of the star closest to us is almost like that of twin brothers.

The Chinchorro were the first in the world to use ritual mummification of the dead. The oldest Chinchorro mummies found are over 9000 years.

Not a cow, but a dog

If in India the cow is revered as a sacred animal, in San Pedro de Atacama the dog is revered. The wits even call it San-Perro-de-Atacama, which translates from Spanish as “the holy dog of the desert. ” True friends of a person in a town of 5,000 are a little less than residents, but almost every dog has a name. Dogs are by no means starving: food and even more valuable drinking water are generously shared with them. Tourists are advised not to be afraid: animals do not touch anyone, they are used to numerous visitors, and it’s a sin to complain about such a dog’s life …

” True friends of a person in a town of 5,000 are a little less than residents, but almost every dog has a name. Dogs are by no means starving: food and even more valuable drinking water are generously shared with them. Tourists are advised not to be afraid: animals do not touch anyone, they are used to numerous visitors, and it’s a sin to complain about such a dog’s life …

Later, NASA tested the Spirit and Opportunity rovers here: both the temperature and the terrain are related to the Red Planet.

…Visitors are surprised that after sunset in San Pedro de Atacama they are not allowed to turn on the electricity – the town plunges into twilight. For savings? No. In order for numerous tourists to enjoy the amazing night sky with perfect visibility (some hotels even got their own telescopes). Seeing such an impressive beauty, people begin to perceive the world in a completely different way. After such a meeting with the vast Universe, they want to live more fully, create and enjoy every day.