Ethnicity of puerto rico: Fast Facts About Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico – World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples

Main languages: Spanish (official), English.

Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic).

Main minority group: Afro-Puerto Ricans 800,000-2.4 million (8%, CIA 2007), Dominicans 100,000 (est., 1.69).

Minority groups include Afro-Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. From 1950, censuses have not included ethnic classification. Moreover, as in other Hispanic Caribbean societies, ethnicity is closely interlinked with income, education and social status.

The majority of Puerto Rican’s regard themselves as being of mixed Spanish-European descent. Recent DNA sample studies have concluded that the three largest components of the Puerto Rican genetic profile are in fact indigenous Taino, European, and African with an estimated 62 per cent of the population having a indigenous female ancestor.

Afro-Puerto Ricans constitute the largest minority group. The country has experienced several waves of migrants. Cubans, Colombians, and Venezuelans have been among the recent immigrants and people from the Dominican Republic now represent a significant foreign minority. There is also a small Asian minority.

Cubans, Colombians, and Venezuelans have been among the recent immigrants and people from the Dominican Republic now represent a significant foreign minority. There is also a small Asian minority.

Chinese

Large numbers of Chinese began arriving in Puerto Rico during the 19th century after the United States Congress passed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. This placed a ten-year moratorium on Chinese immigration to the mainland United States.

Many Chinese came to Puerto Rico to work in constructing the island’s railway system. They remained at the end of their contracts and settled primarily in ‘El Barrio Chino’ (Chinatown) in San Juan.

The Chinese-Puerto Rican minority s is an identifiable segment of Puerto Rican society that has blended Chinese and Hispanic elements into their lives. Many are involved in the restaurant and catering industry or other commercial and professional activities.

Chinese have intermarried with Puerto Ricans from the early years of their presence and many of today’s Chinese-Puerto Ricans have Hispanic last names and are of mixed Chinese and Puerto Rican descent.

Dominicans

Approximately 100,000 Dominicans now live in Puerto Rico, of whom about 30,000 are thought to be illegal immigrants. After New York, Puerto Rico now has the second greatest concentration of Dominicans living outside of the Republic. Dominicans have developed a three-country existence, using Puerto Rico as a staging point for moving on to the USA or back and forth between their homeland. Many have remained in Puerto Rico forming a distinct enclave population. No other sector of Puerto Rico’s population has grown as quickly and Dominicans are now the largest and most visible ethnic minority on the iland.

Environment

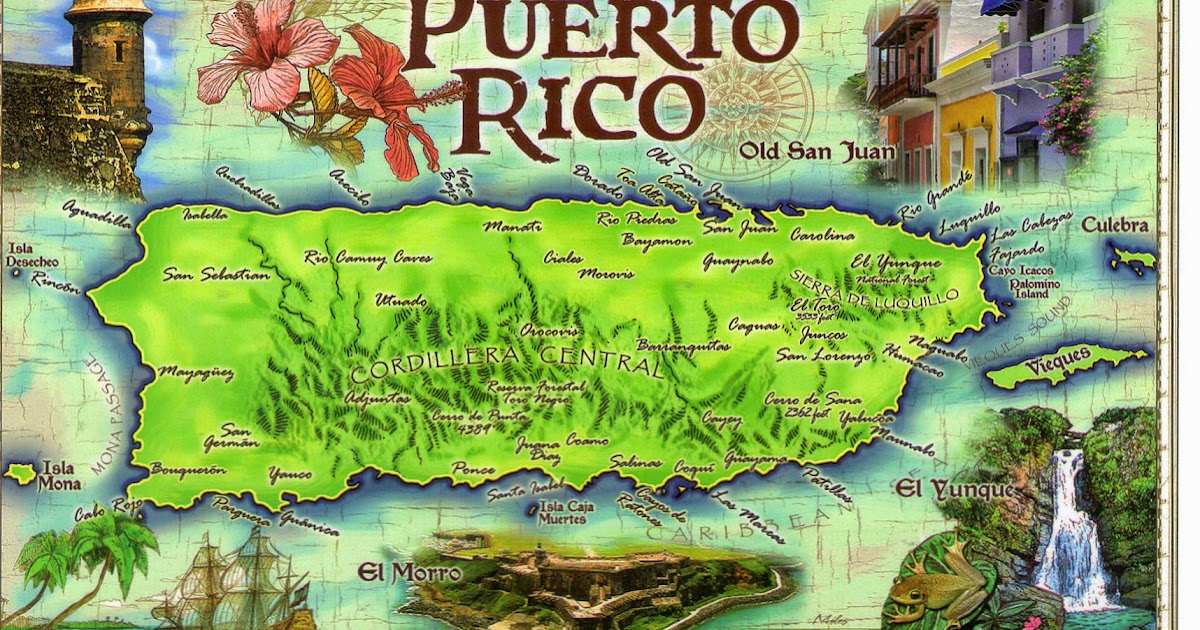

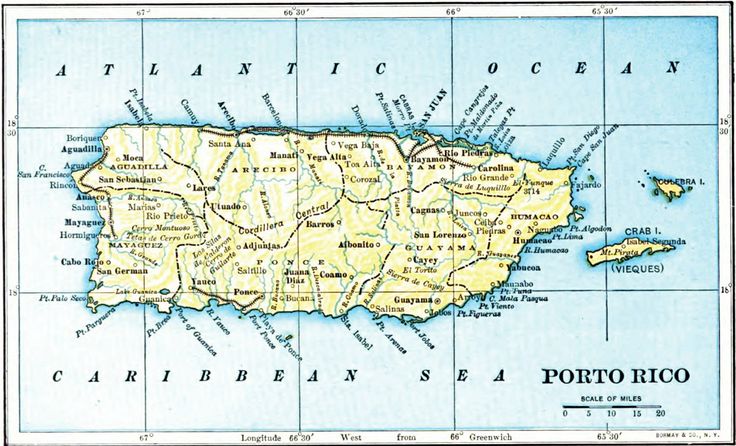

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is the smallest of the Greater Antilles Islands. It is bordered on the north by the Atlantic Ocean, on the south by the Caribbean Sea on the east by the Virgin Passage (which separates it from the Virgin Islands and on the west by the Mona Passage (which separates it from the Dominican Republic). Puerto Rico is composed of the main island and a number of smaller islands. It has a land area of 9104 sq km.

Puerto Rico is composed of the main island and a number of smaller islands. It has a land area of 9104 sq km.

History

Pre-Colombian

The original inhabitants of Puerto Rico are the indigenous Taino who are known to have settled on the island from at least 2000 BCE. Between 120 and 400 AD, Arawak speaking migrants (Igneri) had also canoed up from the Orinoco and joined the original groups all contributing to form the Arawak speaking Taino culture, which was also dominant on nearby Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica and most of the islands of the Caribbean. The original indigenous name for the island was Borikén’ (Spanish ‘Borinquen’)

Early colonial

The island was visited by Columbus during his second voyage (1493). Puerto Rico was first settled by the Spanish in 1509 under the Governorship of Ponce de León. Following initial amicable contact the Spanish established gold mining operations using enslaved indigenous Taino workers. This eventually led to a Taino revolt in 1511 after which many Taino sought refuge off the island or fled into the remote areas and avoided further contact.

It was the abuse of the indigenous Taino labour under Ponce de León in Puerto Rico that would directly set the stage for the later enormous growth of the enslavement of Africans throughout the New World.

Bartholomew de las Casas who had travelled to the New World as an advisor to the governor reported the abuses to the Spanish Court in 1515 and warned of the unsustainability of indigenous enslavement.

Spanish colonists faced increasing difficulties in maintaining an indigenous labour force. They either quickly died or escaped, and with the shortage of labour looming, they argued in favor of the continued need for some form of forced labour to work the mines, build fortifications, and develop the sugar industry.

Bartolomé de las Casas citing potential Christianizing opportunities suggested the importation and enslavement of Africans thereby leading the Spanish Crown in 1517 to permit Spanish colonists to begin importing twelve slaves each.

Mining era

Between 1530 and 1555 the number of enslaved Africans on Puerto Rico rose from 1,500 to 15,000. After being branded on the forehead with a hot iron to indicate their legally purchased status and to prevent theft, they were taken to provide forced labour in the gold mines or on the fledgling ginger and sugar plantations.

After being branded on the forehead with a hot iron to indicate their legally purchased status and to prevent theft, they were taken to provide forced labour in the gold mines or on the fledgling ginger and sugar plantations.

However by 1570, the gold mines on Puerto Rico were considered to be exhausted. Spanish attention turned to much more lucrative precious metal mining areas in Mexico and South America. This left the island to continue being just a garrison for the Spanish merchant ships and gunboats on their way to and from the richer colonies.

Caribbean freemen

In order to populate the island and contribute to the functioning of the garrison and forts an official Spanish edict of 1664 offered freedom and land to free Africans (maroons) wishing to migrate from non-Spanish colonies, such as Jamaica and St Dominique (Haiti).

These individuals with non-Spanish last names moved to Puerto Rico and settled on the western and southern parts of the island. They joined the local militia and fought to defend to territory against attacks from rival British colonizing attempts. Today some of their descendants still have non-Spanish last names.

They joined the local militia and fought to defend to territory against attacks from rival British colonizing attempts. Today some of their descendants still have non-Spanish last names.

The majority of the European and African soldiers, settlers, farmers and enslaved labourers who settled during the early years of the colony arrived without women. Most of these intermarried with the remaining indigenous Taíno creating a mixture of ethnicities that become known as the ‘mestizo’s’ or ‘mulattos’.

Plantation revival

With the French colony of Saint Domingue on nearby Hispaniola having become one of the wealthiest in the world through use of slave labour and with Spain trying to hang onto its few remaining Caribbean territories, Spanish attention once more turned to Puerto Rico as a potentially viable commercial proposition.

However after more than 150 years of abandonment it had acquired a largely mixed population with a significant free Afro-descendant element. With the aim of cashing in on the booming slave trade and turning Puerto Rico into a profitable forced labour agricultural colony, the Spanish Crown issued the ‘Royal Decree of Graces of 1789′.

With the aim of cashing in on the booming slave trade and turning Puerto Rico into a profitable forced labour agricultural colony, the Spanish Crown issued the ‘Royal Decree of Graces of 1789′.

This document set new rules regarding the buying and selling of slaves and added restrictions to the granting of freeman status. It also granted Spanish subjects the right to purchase slaves and to participate in the flourishing business of slave trading and transportation in the Caribbean.

Hundreds of Spanish refugees moved from Hispaniola to Puerto Rico after Spain ceded the western part that island to France (1694), Additionally hundreds more migrated from Spain’ s colony on the Eastern side following the triumph of the Haitian revolution in 1804 and Haiti’s subsequent attempts to annex Santo Domingo (1822-1844). (See Haiti)

These migrants included not only European land owners, and the Africans they had enslaved but also people of mixed European / African ancestry. Some of these refugees would contribute to the development of the Puerto Rican sugar industry.

Royal Decree of Graces

As part of the regional efforts by European colonial governments to halt the spread of rebellions and to bolster European control of the region in 1815 the Spanish government issued the Royal Decree of Graces. This legal order encouraged Spaniards and later Europeans from non-Spanish countries to populate the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The decree provided free land and encouraged the use of slave labour to revive agriculture and to attract new settlers. The new agricultural class that emigrated from Europe sought to acquire slave labour in large numbers to grow labour-intensive agricultural crops.

Hundreds of additional Corsican, Portuguese, French, Lebanese, and Chinese immigrants also arrived during this period. There were also large numbers of immigrants from the Canary Islands and numerous Spanish loyalists from Spain’s former colonies in South America. Other settlers included Irish, Scots, Germans, and other Europeans who were granted land from Spain.

Puerto Rico was one of the last territories to continue importing large numbers of enslaved Africans. In the 19th century Puerto Rico along with Cuba were the Spanish Crown’s leading producers of sugar, coffee, cotton and tobacco.

Creole control

The Spanish government imposed draconian racist laws, such as ‘El Bando contra La Raza Africana’, to control the behavior of all Puerto Ricans of African origin whether slave or free. Local conditions led to a number of uprisings from the early 1820s until 1868 including what is known as El Grito de Lares. All were quickly suppressed but they helped to contribute to the eventual 1873abolition of slavery on Puerto Rico.

The majority of the freed slaves continued working on the same plantations however they did get paid for their labour This arrangement was made considerably easier by the fact that former owners were financially compensated for the loss of their enslaved workforce.

US rule

Puerto Rico was granted autonomy in 1897 and following the Spanish-American War the island was ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Paris in December 1898. The United States established military rule including installing a governor, appointed by the US president and limiting local political activity. In 1917 the US Congress granted Puerto Ricans US citizenship.

The United States established military rule including installing a governor, appointed by the US president and limiting local political activity. In 1917 the US Congress granted Puerto Ricans US citizenship.

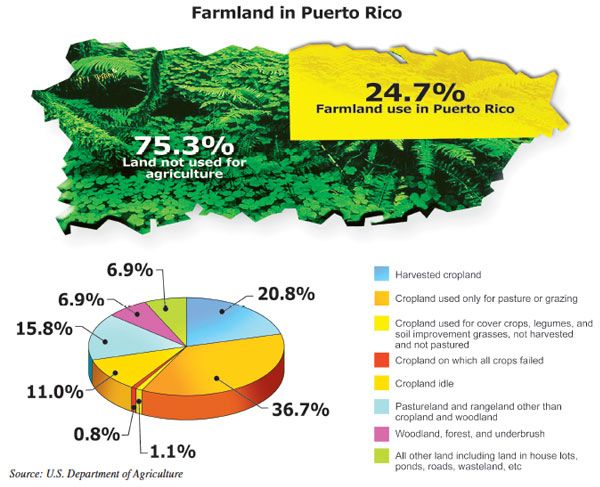

Most of Puerto Rico’s agricultural enterprises were taken over by US conglomerates especially sugar. Puerto Ricans provided the needed cheap labour being almost wholly dependent on agriculture as the only source of national and personal income.

Local political leaders demanded change. Some like Pedro Albizu Campos, would later initiate the nationalist movement in favour of independence. Campos an Afro-Puerto Rican who was accused of conspiring to overthrow the US Government in Puerto Rico, created The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party motivated by the racism he experienced as an officer in an all black unit of the United States Army.

Likewise another Afro-Puerto Rican politician José Celso Barbosa (1857-1921) who is known as the ‘Father of the Statehood for Puerto Rico’ in 1899 founded the pro-statehood Puerto Rican Republican Party.

The emigration of Puerto Ricans off the island began even before citizenship was granted. Unemployed Puerto Rican agricultural workers were sent to work on the sugar plantations of Hawaii in 1899 thereby helping to create the Puerto-Rican Hawaii descendants of today.

The great stimulus to emigration came with the conferring of US citizenship, which enabled Puerto Ricans to travel back and forth without a passport.

Emigration became the preferred option as natural disasters and the Great Depression impoverished the island. Although efforts such as Operation Bootstrap resulted in the increase in manufacturing and a large rise in the general living standard Puerto Ricans continued to opt for migration to the mainland. This mushroomed with the advent of air travel.

In June 1951, Puerto Ricans approved a referendum granting them the right to draft their own constitution. In March 1952 voters approved the new constitution, and on July 25 Governor Muñoz officially proclaimed the island to be the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, a free and associated state.

Governance

Since achieving Commonwealth status the debate over the island’s status has continued as best exemplified by the three main political parties. The Popular Democratic Party (PPD) seeks to maintain or improve the current status, the New Progressive Party (PNP) seeks to fully incorporate Puerto Rico as a US state, and the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) seeks national independence.

As inhabitants of a ‘free and associated state’ of the USA, Puerto Ricans have US citizenship and are free to travel and work in the USA. Since the 1950s Puerto Rico has developed as an offshore manufacturing enclave for US companies, and while wages are lower than in the USA the standard of living is high in comparison to other Caribbean territories.

According to the Bill of Rights, discrimination on grounds of race or colour is illegal. The ‘official’ national ideology of mestizaje stresses the Spanish indigenous heritage, and there is ‘little, if any, ‘national’ emphasis on the African component of Puerto Rican heritage’.

Amnesty International

Tel: + 1 787 763 8318

Website: http://www.amnistiapr.org

Proyecto Caribeño de Justicia y Paz

Tel: + 1 787 751 4617

Email: caribdoc.igc.apc.org; [email protected]; [email protected]

Website: http://pcjp.blogspot.com

Centro De Investigación Económica Para El Caribe (DOMINICAN REPUBLIC)

Tel: + 1 809 563 9838

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.cieca.org

Publications

We haven’t made any publications about this country or territory.

News and updates

No posts match your query.

Active programmes

No active programme page is currently available for this country or territory.

Past programmes

We haven’t organized any programmes in this country or territory.

Puerto Rico ponders race amid surprising census results

By DÁNICA COTOOctober 15, 2021 GMT

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico (AP) — The number of people in Puerto Rico who identified as “white” in the most recent census plummeted almost 80%, sparking a conversation about identity on an island breaking away from a past where race was not tracked and seldom debated in public.

The drastic drop surprised many, and theories abound as the U.S. territory’s 3.3 million people begin to reckon with racial identity.

“Puerto Ricans themselves are understanding their whiteness comes with an asterisk,” said Yarimar Bonilla, a political anthropologist and director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York. “They know they’re not white by U.S. standards, but they’re not Black by Puerto Rico standards.”

Nearly 50% of those represented in the 2020 census — 1.6 million of 3.29 million — identified with “two races or more,” a jump from 3% — or some 122,200 of 3.72 million — who chose that option in the 2010 census. Most of them selected “white and some other race.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, more than 838,000 people identified as “some other race alone,” a nearly 190% jump compared with some 289,900 people a decade ago, although Bonilla said Census Bureau officials have yet to release what races they chose. Experts believe people likely wrote “Puerto Rican,” “Hispanic” or “Latino,” even though federal policy defines those categories as ethnicity, not race.

Among those who changed their response to race was 45-year-old Tamara Texidor, who selected “other” in 2010 and this time opted to identify herself as “Afrodescendent.” She said she made the decision after talking to her brother, who was a census worker and told her how people he encountered when he went house to house often had trouble with the question about race.

Texidor began reflecting about her ancestry and wanted to honor it since she descended from slaves on her father’s side.

“I’m not going to select ‘other,’” she recalled thinking when filling out the census. “I feel I am something.”

Experts are still debating what sparked the significant changes in the 2020 census. Some believe several factors are at play, including tweaks in wording and a change in how the Census Bureau processes and codes responses.

Bonilla also thinks a growing awareness of racial identity in Puerto Rico played a part, saying that “extra intense racialization” in the past decade might have contributed. She and other anthropologists argue that change stemmed from anger over what many consider a botched federal response to a U.S. territory struggling to recover from Hurricane Maria and a crippling economic crisis.

She and other anthropologists argue that change stemmed from anger over what many consider a botched federal response to a U.S. territory struggling to recover from Hurricane Maria and a crippling economic crisis.

“They’ve finally understood that they’re treated like second-class citizens,” Bárbara Abadía-Rexach, a sociocultural anthropologist, said of Puerto Ricans.

ADVERTISEMENT

Another critical change in the 2020 census was that only a little over 228,700 identified solely as Black or African American, a nearly 50% drop compared with more than 461,000 who did so a decade ago. The decline occurred even as grass-roots organizations in Puerto Rico launched campaigns to urge people to embrace their African heritage and raised awareness about racial disparities, although they said they were encouraged by the increase in the “two or more races” category.

Bonilla noted Puerto Rico currently has no reliable data to determine whether such disparities have occurred during the pandemic, noting that there is no racial data on coronavirus testing, hospitalizations or fatalities.

The island’s government also does not collect racial data on populations, including those who are homeless or incarcerated, Abadía-Rexach added.

“The denial of the existence of racism renders invisible, criminalizes and dehumanizes many Black people in Puerto Rico,” she said.

The lack of such data could be rooted in Puerto Rico’s history. From 1960 to 2000, the island conducted its own census and never asked about race.

“We were supposed to be all mixed and all equal, and race was supposed to be an American thing,” Bonilla said.

Some argued at the time that Puerto Rico should be tracking racial data while others viewed it as a divisive move that would impose or harden racial differences, a view largely embraced in France, which does not collect official data on race or ethnicity.

For Isar Godreau, an anthropologist and professor at the University of Puerto Rico, that type of data is crucial.

“Skin color is an important marker that makes people vulnerable to more or less racial discrimination,” she said.

The data helps people fight for racial justice and determines the allocation of resources, Godreau said.

The major shift in the 2020 census — especially how only 560,592 people identified as white versus more than 2.8 million in 2010 — comes amid a growing interest in racial identity in Puerto Rico, where even recent surveys about race prompted responses ranging from “members of the human race” to “normal” to “I get along with everyone.” Informally, people on the island use a wide range of words to describe someone’s skin color, including “coffee with milk.”

That interest is fueled largely by a younger generation: They have signed up for classes of bomba and plena — centuries-old, percussion-powered musical traditions — as well as workshops on how to make or wear headwraps.

More hair salons are specializing in curly hair, eschewing the blow-dried results that long dominated professional settings in the island. Some legislators have submitted a bill that cites the results of the 2020 census and that if approved would make it illegal to discriminate against someone based on their hair style. Several U.S. states already have similar laws.

Several U.S. states already have similar laws.

As debate continues on what sparked so many changes in the 2020 census, Bonilla said an important question is what the 2030 census results will look like. “Will we see an intensification of this pattern, or will 2020 have been kind of a blip moment?”

about race – Translation into Russian – examples English

Premium

History

favorites

Advertising

Download for Windows It’s free

Download our free app

Advertising

Advertising

No ads with Premium

These examples may contain rude words based on your search.

These examples may contain colloquial words based on your search.

about race

about the race

about racial

about races

about racing

in race

about race

about race

pro race

about race

about race

about racing

Suggestions

race about

Our writers and speakers often get asked questions about race and racism.

Our writers and speakers are often asked questions about race and racism.

It may be challenging because the cultural differences, but I don’t really care about race and ethnicity.

It might not be easy because of cultural differences, but I don’t really care about race and ethnicity.

It is possible even to speak about race of sea arms in the region .

You can even talk about the naval arms race in the region.”

How do you talk about race with your children?

SC: how do you talk about racing with your son?

It wasn’t about race riots.

It’s not about about race riots .

They hear about race , pollution, war, abortion, ecology, and myriad other moral problems.

They hear about racial conflicts, environmental pollution, wars, abortions, ecology and a host of other moral issues.

However, this is also the reason for a taboo for the local people – all talks about race are banned.

However, this is also a taboo cause for the locals – all talk about the race is forbidden.

There is, however, a danger that it will have an adverse affect on the necessary national discussion about race .

However, there is a danger that this will adversely affect the necessary national discussions about race .

because you cannot talk about race without talking about privilege.

because it’s impossible to talk about race without talking about privilege.

Shea, not everything’s about race .

Shi, that you are all about race .

I agree, but you guys keep asking me about race .

I agree, but you keep asking me about race .

Today, the persona he created opens up a dialogue about race , fame, and surprising flexibility of truth.

Today, the stage image he created generates a dialogue about race , fame and amazing flexibility in perceiving the truth.

I’m not talking to white people about race unless I absolutely have to.

I don’t talk to whites about race unless I have absolutely no other choice.

My dad and I often talked about race and racism.

Our writers and speakers are often asked 9 questions0051 about race and racism.

Posting controversial statements on your social media about race , religion, or politics.

Posting controversial statements on social media about race, religion or politics.

These twin sisters make us rethink everything we know about race

The caption reads: “These twins make us rethink everything we know about race “.

And then people think ONLY about race .

Now all thoughts are only about race .

The findings of the study being conducted by the Anthropology Center about race relations and ethnicity should be summarized in the next report.

The next report should include a summary of the findings of the study conducted by the Center for Anthropology on Question about race relations and ethnicity.

He told the unadulterated, politically incorrect truth about race in America.

He told the genuine, politically incorrect truth about the race in America.