Puerto rico colonization: Why Isn’t Puerto Rico a State?

It Is 2020, and Puerto Rico Is Still a Colony

Earlier this year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a historical bill to advance statehood for Washington, D.C., acknowledging that the capital’s 700,000 residents lack proper representation in Congress. However, the same could be said for over 3 million U.S. citizens in Puerto Rico, who have for decades been in a similar struggle to no avail.

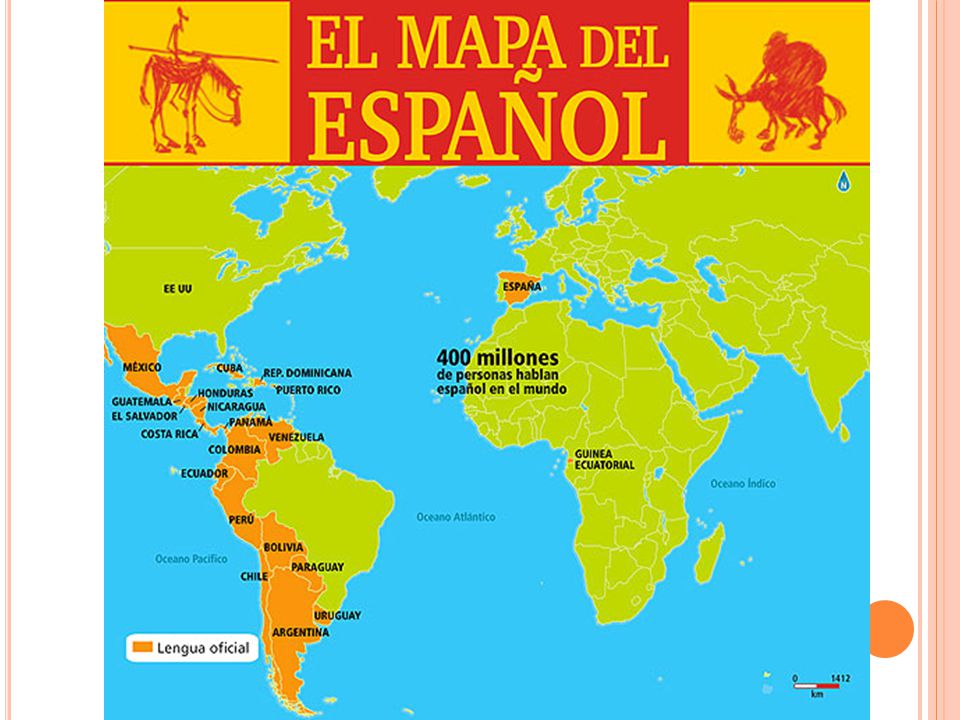

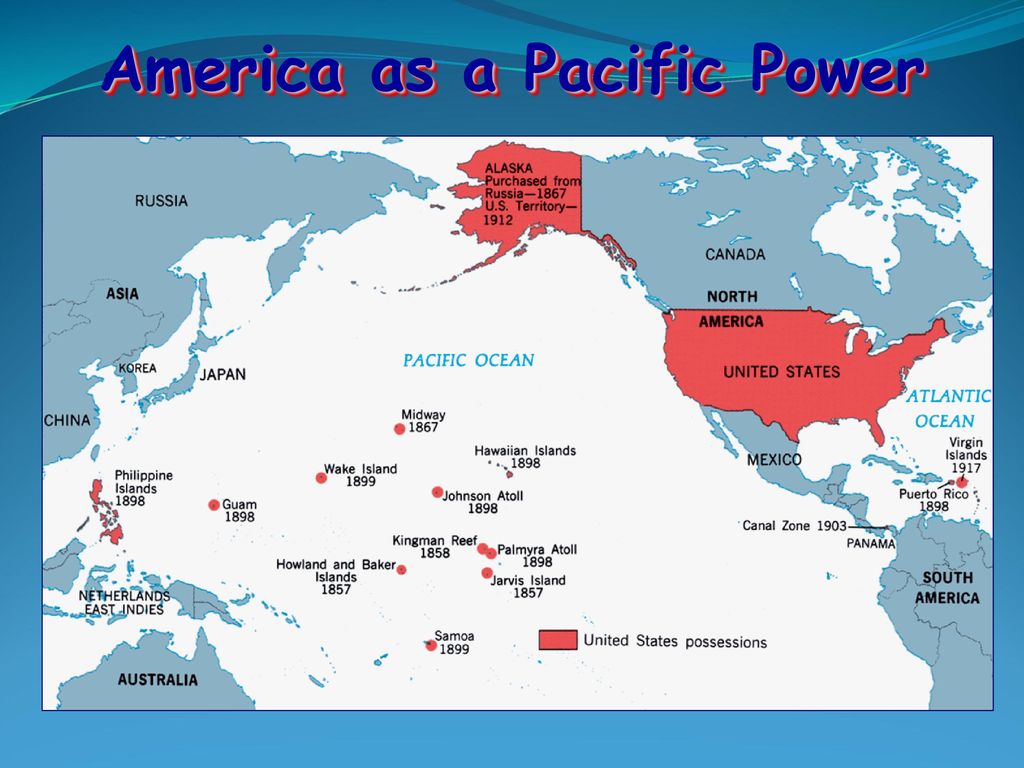

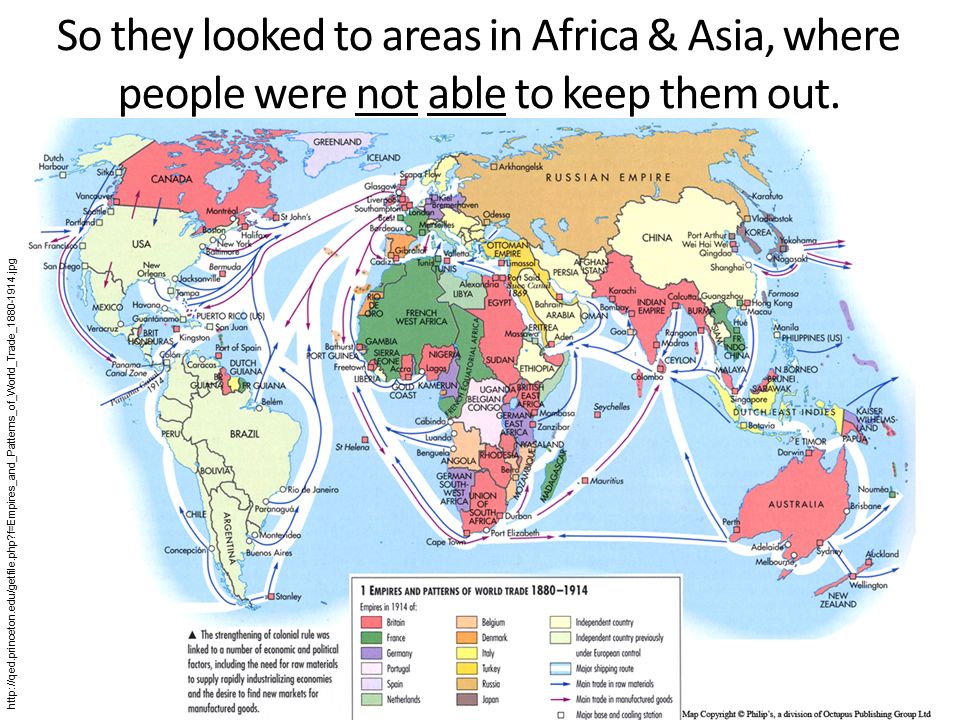

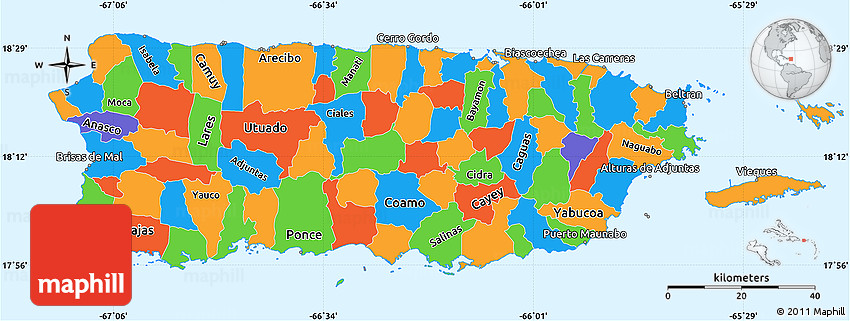

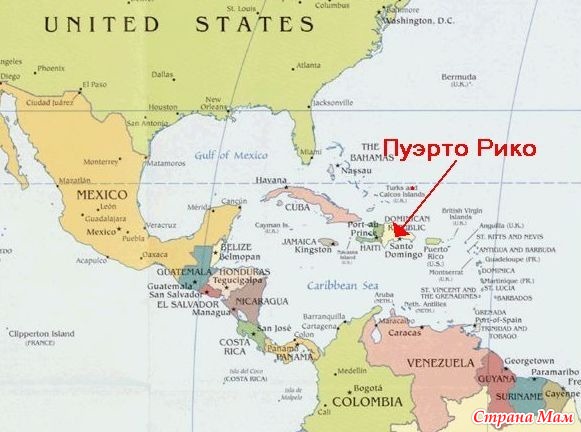

Puerto Rico’s relationship with the U.S. is rooted in a history of discrimination. The island has been a territory of the United States since Spain ceded it in 1898, following America’s invasion of it during the Spanish-American War. Three years later, the Insular Cases of 1901 made clear that Puerto Ricans were bound to an unequal, colonial relationship grounded in racism in which the island’s residents were seen as inferior: The cases state the island is “inhabited by alien races” that could not understand “Anglo-Saxon principles,” and is, as a territory, “belonging to the United States, but not a part of the United States. ” The Constitution’s territorial clause gives Congress the power to determine which parts of the Constitution apply to territories and which do not; accordingly, Puerto Ricans were not granted citizenship until 1917, and only then so that they could serve in World War I. It took until 1947 for the people of the island to be given the right to vote for their own governor. Even today, only about half of American adults know that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens.

” The Constitution’s territorial clause gives Congress the power to determine which parts of the Constitution apply to territories and which do not; accordingly, Puerto Ricans were not granted citizenship until 1917, and only then so that they could serve in World War I. It took until 1947 for the people of the island to be given the right to vote for their own governor. Even today, only about half of American adults know that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens.

As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico has a single non-voting delegate in Congress: its resident commissioner, representing a constituency that would be entitled to five seats and votes if it were located anywhere else in the nation. The island also is over 70 billion dollars in debt, but lacks many of the bankruptcy protections available to states. Scholars, politicians and activists agree that the current political status is unfair and unsustainable, but pro-statehood, pro-commonwealth and pro-independence perspectives constantly clash when looking for solutions.

This November, the island held its third status referendum of the decade, but regardless of its results — which favored statehood — the vote seems inconsequential. True power to amend Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the United States lies in the hands of the seemingly complacent federal government, where the people of the island have no representation. The nation’s legislators must heed the call of Puerto Ricans and make moving forward with a process of self-determination a priority.

Current Status and Political Perspectives

The question of status shapes Puerto Rican politics. The island’s main political parties are assembled based not on how liberal or conservative their ideologies are, but rather on what association with the U.S. they think is best for the island. The two biggest forces are the pro-statehood Partido Nuevo Progresista, or New Progressive Party, and the pro-commonwealth Partido Popular Democrático, or Popular Democratic Party. Both encompass diverse perspectives and have ties to the Democratic and Republican Parties, but within each party, its members agree on what relationship would be best for the island to have with the United States. The Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño, or Puerto Rican Independence Party, has also existed since 1946, but fails to garner electoral support of the same scale.

Both encompass diverse perspectives and have ties to the Democratic and Republican Parties, but within each party, its members agree on what relationship would be best for the island to have with the United States. The Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño, or Puerto Rican Independence Party, has also existed since 1946, but fails to garner electoral support of the same scale.

Still, there is a general consensus among all of these parties that the current association is flawed. As Luis Fortuño, a former governor and resident commissioner from the pro-statehood PNP, told the HPR, “To believe that we can continue to live in this limbo forever simply makes no sense and puts us at a disadvantage.”

Fortuño claims that these disadvantages are partly responsible for Puerto Rico’s population decline. The Puerto Rican diaspora has seen the amount of Puerto Ricans living in the 50 states increase to nearly 6 million in 2018, from about 4.5 million in 2010. “The population of Puerto Rico is not only fewer people now, but it’s older,” explained Fortuño. “The younger population tends to leave the island because they see opportunities elsewhere.”

“The younger population tends to leave the island because they see opportunities elsewhere.”

Even some members of the pro-commonwealth PPD acknowledge the need for reform. Aníbal Acevedo Vilá, who has also served as Puerto Rico’s governor and resident commissioner, confirmed this to the HPR: “I don’t think anybody is happy with the current relationship as it is … What we [members of the PPD] all agree on is that we want a relationship of association with the United States that is not subject to the plenary powers of Congress.”

Those plenary powers give Congress, in which the island has no true representation, power to pass bills that shape the island’s future, like the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act. PROMESA, passed in 2016, established “an Oversight Board to assist the Government of Puerto Rico … in managing its public finances, and for other purposes.” The Board members are appointed by the U.S. president, with the exception of an ex officio member designated by the governor of Puerto Rico, and have sweeping power over the local budget and economy. The Board’s main mission is “to create the necessary foundation for economic growth and to restore opportunity to the people of Puerto Rico,” but since its appointment, the island has seen many austerity measures go into effect under the body’s oversight, including cuts to the pensions of over 65,000 retirees and the closure of 283 public schools.

The Board’s main mission is “to create the necessary foundation for economic growth and to restore opportunity to the people of Puerto Rico,” but since its appointment, the island has seen many austerity measures go into effect under the body’s oversight, including cuts to the pensions of over 65,000 retirees and the closure of 283 public schools.

The imposition of such a board demonstrates that, like in 1901, the U.S. still believes Puerto Rico to be somewhat incapable of governing itself. On June 1, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the Board’s appointment after a challenge to PROMESA argued that the appointment of local officers by Congress was unconstitutional. “Congress has ‘full and complete legislative authority over the people of the Territories and all the departments of the territorial governments,’” concurred Justice Clarence Thomas, citing an 1880 decision.

The fact that Puerto Rico is subject to the powers of this federally appointed board, of which no member is elected by people of the island, seems like a near-perfect example of colonialism. Gretchen Sierra-Zorita, an active advocate for Puerto Rican’s rights in Washington, concurs. “I think it’s important to use the word colony … Americans do not see themselves as a colonial empire, because it’s not taught in their schools,” Sierra-Zorita told the HPR.

Gretchen Sierra-Zorita, an active advocate for Puerto Rican’s rights in Washington, concurs. “I think it’s important to use the word colony … Americans do not see themselves as a colonial empire, because it’s not taught in their schools,” Sierra-Zorita told the HPR.

Juan Dalmau, the only pro-independence PIP senator currently in the Puerto Rican Senate, also considers the distinction important, arguing that Puerto Rico is a nation in itself, with its own history, language and way of thought. In an interview with the HPR, Dalmau stated, “Contrary to Rosa Parks, who fought because she wanted to sit in the front of the bus and wanted to have equal rights, we think that Puerto Ricans, as a nation, have to aspire to drive their own bus.” According to Dalmau, the island would forever be subject to the rest of the nation’s wishes with any type of association, even as a state.

In short, politicians across the island have different ideas of what they want Puerto Rico to look like — but none of them desire a future that is similar to the island’s present.

The 2020 Referendum

Recent challenges have underscored the urgency of reevaluating Puerto Rico’s status. After Hurricane Maria struck in 2017, federal aid was slow to arrive and insufficient. A similar situation played out after earthquakes rattled the island in early 2020. It is impossible to know whether these responses would have been any different if Puerto Rico were a state, but there are clear differences from the aid states have received for comparable disasters. These differences exacerbate disparities in health care, education and more.

Some members of the PNP see these events as a spotlight on the unequal status that Puerto Rico possesses in the nation and, as a result, avidly promote the new referendum as a solution. However, the referendum has been met with opposition from the PPD and the PIP. When asked about the plebiscite, Eduardo Bhatia, the PPD minority leader in the Puerto Rican Senate, said, “It’s a totally local decision made by the governor [Wanda Vázquez] to cheat and lie to the people. ” Bhatia claims the vote is insignificant and meant to reduce the impact of the very problematic term the PNP has had while in control the last four years.

” Bhatia claims the vote is insignificant and meant to reduce the impact of the very problematic term the PNP has had while in control the last four years.

Vázquez’s political problems largely stem from what is often referred to as TelegramGate. After a Telegram text chat in which former Governor Ricardo Roselló and several members of his cabinet used homophobic, sexist and racist language was leaked in the summer of 2019, people took to the streets to demand his resignation. When he and much of his cabinet resigned, the responsibility of governing fell upon then-Secretary of Justice Vázquez. Vázquez said she would only serve until the end of this term but announced her campaign for reelection toward the end of 2019 and was defeated in the primaries earlier in 2020. “Many members of the New Progressive Party had decided to not vote [in 2020], to stay home … They are trying to grasp whatever she can to try to see if she can muster a majority,” Bhatia claimed.

Bhatia’s point could perhaps be substantiated by the unique way this referendum poses the question of the island’s status: It does not ask Puerto Ricans which option they prefer, as the question has mostly been constructed before, but rather asks for a “yes” or “no” response to becoming a state. The “yes” majority vote that was favored will establish a seven-member commission that would develop a transition plan to be presented to Congress. A similar outcome would have resulted from a “no” majority vote, but their plan would not include statehood in the solution.

The “yes” majority vote that was favored will establish a seven-member commission that would develop a transition plan to be presented to Congress. A similar outcome would have resulted from a “no” majority vote, but their plan would not include statehood in the solution.

Even leaders in the PNP acknowledge that this vote will not be the island’s saving grace — but they still believe in the vote itself. “When something is difficult to attain, it is because it is worthwhile,” argued Fortuño. “It is going to be a process, and I believe this November’s vote is part of a process, not the beginning nor the end.” After all, Puerto Rico held referendums on status in 1967, 1993, 1998, 2012 and 2017, but Congress has not been engaged in the process or seemed to care about any of them.

If this was a move by the PNP to get their voters out, it seems to have worked. Their candidate for governor, Pedro Pierluisi, won the election with merely 33% of the popular vote, highlighting how the two traditional Puerto Rican parties, the PNP and PPD, have been steadily losing ground the past few elections.:strip_icc()/pic1381193.png) Smaller parties such as the PIP, the left-leaning Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana (Citizen’s Victory Movement), and the right-leaning Proyecto Dignidad (Dignity Project) will all hold seats in the Puerto Rican legislature these next four years.

Smaller parties such as the PIP, the left-leaning Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana (Citizen’s Victory Movement), and the right-leaning Proyecto Dignidad (Dignity Project) will all hold seats in the Puerto Rican legislature these next four years.

If no locally designed referendums have led to anything, maybe it is time that Puerto Rico tried something different. Sadly, however, the island cannot do this alone. Sierra-Zorita believes the vote on status in 2020 will have no consequences, but she also said a potential alternative could be a binding referendum drafted in cooperation with Congress.

However, Puerto Rico’s path to statehood is not straightforward, and would certainly face opposition. It is not unusual to see progressive activists calling for outright Puerto Rican statehood, but Sierra-Zorita noted, “Whenever non-Puerto Rican people … talk about, with very good intentions, that we should be a state — it’s like, that’s not up to you to decide, it’s up to Puerto Ricans, and I feel really strongly and am irritated by that kind of talk. ” The concept of self-determination is based on giving Puerto Ricans the power to decide their own fate. Imposing statehood would be as coercive as the island’s current status.

” The concept of self-determination is based on giving Puerto Ricans the power to decide their own fate. Imposing statehood would be as coercive as the island’s current status.

The Path to Change

When talking about changes to Puerto Rico’s relationship to the U.S., the island is downplayed and constantly portrayed as a burden. Puerto Rico’s $70 billion debt cannot be overlooked. However, we do not contextualize the debt with the fact that Puerto Rico is subject to the Jones Act, which means Puerto Rico can only receive goods shipped from U.S. ports on American-owned ships, greatly benefiting the nation at the island’s expense. Studies have concluded that without the Jones Act, Puerto Rico could have gained nearly $1.5 billion of economic activity and 13,250 jobs. Similarly, we ignore the fact that the U.S. Navy controlled over 26,000 acres of Puerto Rican land on the island of Vieques from 1941 to 2003, a large part of which they rented out to other armed forces for profits of over $80 million a year. Moreover, most U.S. companies pay virtually no taxes to the Puerto Rican government. The island’s colonial status has hindered economic development and continues to do so.

Moreover, most U.S. companies pay virtually no taxes to the Puerto Rican government. The island’s colonial status has hindered economic development and continues to do so.

This presidential election was undeniably consequential for Puerto Rico. President Donald Trump has said statehood for Puerto Rico is an “absolute no,” and Mitch McConell vehemently opposes it as well, but the Republican Platform of 2016 fully supported statehood. President-elect Joe Biden, on the other hand, wrote a column claiming he would favor “a process of self-determination, listening and developing federal legislation that outlines a fair path forward.”

Though statehood for Puerto Rico is unlikely to pass in Mitch McConell’s Senate, Congress should show the same level of concern for the rights of the disenfranchised citizens of Puerto Rico that they do for those in D.C. The United States benefits from having Puerto Rico as a colony, but at the expense of the Puerto Rican people. Senators like Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass. , and Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., have introduced bills that could provide debt relief for Puerto Rico; however, it is time for Congress to tackle the root of Puerto Rico’s issue and seek to amend its status through a process of self-determination.

, and Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., have introduced bills that could provide debt relief for Puerto Rico; however, it is time for Congress to tackle the root of Puerto Rico’s issue and seek to amend its status through a process of self-determination.

Not only Puerto Ricans living in the states but all Americans should care about their fellow citizens on the island and hold their representatives accountable to help break the vicious cycle in which Puerto Rico has been stuck: waiting for Congress, in which they have no say, to care about its people’s rights and representation. Until that shift, it seems like the island’s plight will go unanswered, and its residents will keep bearing the brunt of colonialism.

Image Credit: “US and Puerto Rican flags on a car in San Juan, Puerto Rico” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

– Advertisement –

– Advertisement –

Latest Articles

Popular Articles

– Advertisement –

More From The Author

five things you should know – Liberation News

Photo credit: Ricardo Figueroa / Flickr

Puerto Rico is still reeling from the devastation left in the wake of Hurricane Fiona, which hit the island on September 18 bringing with it historic flooding and landslides. At least a dozen people have died and thousands more required emergency rescue. Fiona’s arrival came only two days before the 5-year anniversary of superstorm Hurricane Maria which pummeled Puerto Rico in 2017, killing over 4,000 people and leaving millions more without power — some for up to a year. Five years later, the island is once again in darkness and Puerto Ricans are left to fend for themselves. Here are five things you should know about hurricanes in Puerto Rico and why this keeps happening.

At least a dozen people have died and thousands more required emergency rescue. Fiona’s arrival came only two days before the 5-year anniversary of superstorm Hurricane Maria which pummeled Puerto Rico in 2017, killing over 4,000 people and leaving millions more without power — some for up to a year. Five years later, the island is once again in darkness and Puerto Ricans are left to fend for themselves. Here are five things you should know about hurricanes in Puerto Rico and why this keeps happening.

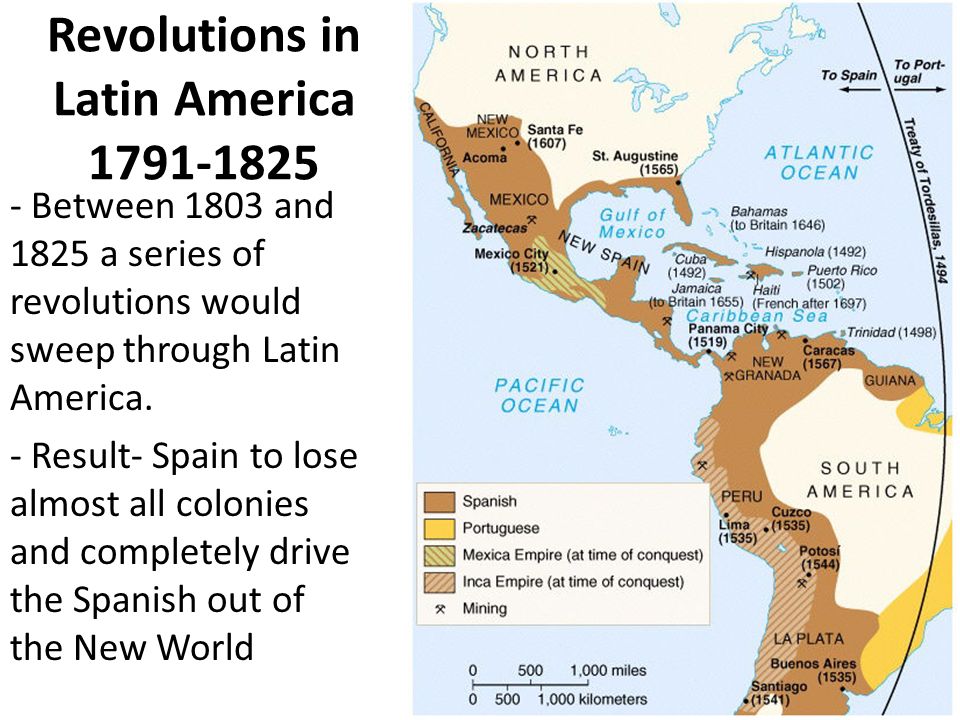

- Puerto Rico is one of the oldest colonies in the world

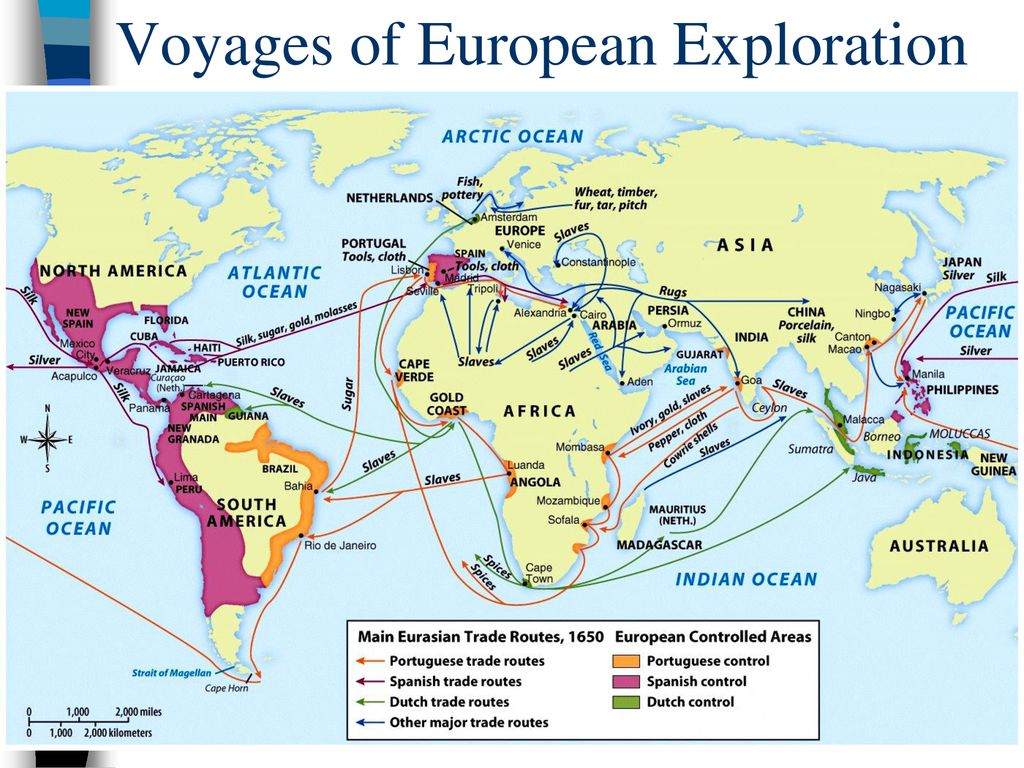

Originally inhabited by the Taínos and known as Boríken, the island was invaded by the Spanish 529 years ago during Columbus’ second voyage. Later, the United States would seize control of it in 1898 as an imperialist spoil of the Spanish-American War. Today, over a hundred years have passed since its forced annexation, yet Puerto Rico remains in a state of legal limbo and Puerto Ricans have second class citizenship. Puerto Ricans have essentially no control over their economy, they are unable to vote for president or Congress, and yet are forced to live under U.S. laws.

Puerto Ricans have essentially no control over their economy, they are unable to vote for president or Congress, and yet are forced to live under U.S. laws.

Puerto Rico has a poverty rate of 43.5%, surpassing that of Mississippi, the poorest U.S. state. As a result, millions of Puerto Ricans have been forcefully displaced throughout the decades — some 200,000 of whom were forced to evacuate the island as a direct result of Hurricane Maria in 2017. Puerto Rico’s colonial status doesn’t just exacerbate the island’s myriad social and economic issues, it is the root cause of them.

The underdevelopment that centuries of colonialism has caused makes Puerto Rico increasingly vulnerable to natural catastrophes. Hurricanes are an inevitable reality for many Caribbean islands, but their imminence means that local governments and federal disaster relief agencies like FEMA should be able to plan for them accordingly. In Puerto Rico, hurricanes have a habit of unmasking Washington’s refusal to do so, and thus the dire reality of colonialism on the island.

- Hurricanes in Puerto Rico are inevitable, disaster colonialism is not

Five years ago on September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico. It was a Category 5 storm — the strongest to impact the island in nearly 90 years — and it left unimaginable damage in its wake. While Puerto Ricans went months without power, water or adequate shelter as a result, then President Donald Trump lied about the death toll on his Twitter account, claiming that between 6 to18 people had passed away. In reality, over 4,000 Puerto Ricans died in the aftermath of Maria. Most were not victims of the storm itself, but of the gross government neglect that Puerto Rico experienced afterward as FEMA and the White House dragged their feet to deliver vital aid.

Long after the storm subsided, the number of fatalities continued to rise as a result of solvable, secondary issues. Take for example, the 26 post-Maria deaths attributed to Leptospirosis, a potentially fatal bacterial infection that spread through the island as survivors were forced to drink fluids containing rodent waste in the absence of clean drinking water. Some two years after Maria, tens of thousands of water bottles issued by FEMA were found abandoned in fields, unopened and expired, never having been distributed to those that so desperately needed them.

Some two years after Maria, tens of thousands of water bottles issued by FEMA were found abandoned in fields, unopened and expired, never having been distributed to those that so desperately needed them.

Despite such blatant unpreparedness for Maria, the Puerto Rican colonial government has done little to prepare for the next storm in the five years since. Repairs to damaged homes and infrastructure across the island were slated to begin in 2017, yet today, thousands of homes and roads have yet to be fixed. The government has completed only 21% of more than 5,500 planned repair projects and much of what was completed was done poorly. When Fiona hit on Sunday, upwards of 3,600 homes on the island still did not have roofs. In Utuado, a municipality in the central region of the island, viral video footage showed a bridge rebuilt after Hurricane Maria being swept away by aggressive flood waters.

The arrival of Fiona has put even more strain on this already weakened infrastructure. The storm dropped record amounts of rain and caused catastrophic flooding. Early on Sunday, 100% of the island experienced power outages. With no power, people are forced to rely on cumbersome and unreliable backup generators that require expensive diesel fuel to operate, making them inaccessible to many. After Maria, some municipalities went for an entire year without power. This time, Governor Pedro Pierluisi has publicly admitted that thousands will again have to endure “several days” without power. From experience, Puerto Ricans know that “several days” can easily turn into months. Currently, nearly half of the island is still without electricity.

The storm dropped record amounts of rain and caused catastrophic flooding. Early on Sunday, 100% of the island experienced power outages. With no power, people are forced to rely on cumbersome and unreliable backup generators that require expensive diesel fuel to operate, making them inaccessible to many. After Maria, some municipalities went for an entire year without power. This time, Governor Pedro Pierluisi has publicly admitted that thousands will again have to endure “several days” without power. From experience, Puerto Ricans know that “several days” can easily turn into months. Currently, nearly half of the island is still without electricity.

Compare these abysmal relief efforts to the hurricane responses of another Caribbean country, Cuba. In 1959, Cuba waged a successful revolution against imperialist forces on the island, putting an end to the legacy of colonialism that had historically underdeveloped the nation. Shortly thereafter in 1966, the revolutionary government established a civil defense system that became a global model for disaster relief efforts. Today, disaster preparation and response in Cuba saves lives. In 2004 for example, Hurricane Jeanne killed 3,000 people in Haiti, but none in Cuba, even though Cuba was hit harder. A 2004 United Nations press release praises the island as a leader in disaster preparedness despite the U.S.-imposed blockade that makes it difficult for them to obtain emergency disaster supplies. A side by side comparison of Cuba and Puerto Rico’s hurricane track record makes it clear that it is a capitalist response to disasters, not the disasters themselves, that pose the real problem.

Today, disaster preparation and response in Cuba saves lives. In 2004 for example, Hurricane Jeanne killed 3,000 people in Haiti, but none in Cuba, even though Cuba was hit harder. A 2004 United Nations press release praises the island as a leader in disaster preparedness despite the U.S.-imposed blockade that makes it difficult for them to obtain emergency disaster supplies. A side by side comparison of Cuba and Puerto Rico’s hurricane track record makes it clear that it is a capitalist response to disasters, not the disasters themselves, that pose the real problem.

- U.S. corporations profit off disasters and privatization in Puerto Rico

Why does this pattern of disregard exist and what motive does the United States have to continuously fumble repair efforts and delay assistance? Simply put, the U.S. ruling class profits from disasters in Puerto Rico. After Hurricane Maria, PREPA, Puerto Rico’s government-owned utility system, awarded $4. 4 billion in contracts to corporations for services related to hurricane reconstruction and necessary repair work to the electrical grid. A whopping $3.7 billion of those contracts went to U.S.-owned private companies.

4 billion in contracts to corporations for services related to hurricane reconstruction and necessary repair work to the electrical grid. A whopping $3.7 billion of those contracts went to U.S.-owned private companies.

PREPA and the Puerto Rican government are notorious for favoring private companies over local workers and unions. UTIER is the labor union that represents PREPA workers and is one of the leading forces in the fight against the privatization of Puerto Rico’s grid. According to union leaders, in one case, PREPA paid a Florida-based corporation to repair street lights in Puerto Rico at a rate of over $400 per unit, even though local union workers offered to do the same work for only around $60.

This trend extends beyond contracts awarded by PREPA. FEMA, for example, awarded $156 million to Tribute Contracting LLC, a one-person company based out of Atlanta who promised to deliver 30 million emergency meals to survivors of Maria. Only 50,000 of those meals — less than 0. 2 percent — were ever delivered. Such corruption plagues relief efforts in Puerto Rico — purposeful mismanagement funnels life-saving aid out of the island and into U.S. corporate accounts.

2 percent — were ever delivered. Such corruption plagues relief efforts in Puerto Rico — purposeful mismanagement funnels life-saving aid out of the island and into U.S. corporate accounts.

Unsurprisingly, the United States’ relationship with Puerto Rico has always been one based on extraction of profit. U.S. corporations squeeze billions of dollars from the island annually. Yet, mind bogglingly, Puerto Rico owes a staggering $72 billion in debt to Washington. In June of 2016, President Barack Obama signed PROMESA, Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, into law, which established a Fiscal Oversight Board colloquially known as “La Junta.” Tasked with overseeing the repayment of the island’s debt, La Junta itself is largely a foreign body — its members are chosen by the U.S. president and Congress and are unaccountable to Puerto Rican residents.

Many of the board members have ties to multinational corporations and have increased a push towards privatization on the island as a way to line the pockets of foreign creditors. With leeway to make sweeping executive changes to the island’s economy, La Junta has established an austerity regime in Puerto Rico, systematically cutting funding for vital public services in order to pay the colonial piper.

With leeway to make sweeping executive changes to the island’s economy, La Junta has established an austerity regime in Puerto Rico, systematically cutting funding for vital public services in order to pay the colonial piper.

The privatization of PREPA is a prime example. On June 22, 2021, despite Puerto Rico’s House of Representatives voting unanimously against the contract, La Junta announced that LUMA would assume control of the formerly public electrical grid. The announcement was met with sustained outcry from Puerto Ricans, who were kept in the dark regarding contract negotiations. LUMA, an American and Canadian owned utility company, laid off hundreds of UTIER workers, refusing to honor their contracts and agreeing only to interview workers should they decide to reapply. As a stipulation, any workers who were rehired would have to relinquish their pensions and other benefits. Many of the workers — most of whom had years of experience as linemen on the grid — declined these arrangements, resulting in a dangerous labor shortage leading up to hurricane season.

To justify layoffs, Puerto Rico’s government argued that LUMA would modernize the island’s electrical grid and make the cost of electricity more affordable for residents. In reality, PREPA’s privatization was a way to outsource service and boost profits. Even in the absence of storms like Fiona, outages in Puerto Rico have been frequent and long lasting since LUMA took over. Utility bills for individuals have also skyrocketed.

LUMA’s response to the public outrage, like that of Governor Pierluisi, has been entirely dismissive. In June, for example, the corporation held a press conference to address the constant blackouts. Reprehensibly, they conducted it entirely in English, refusing to provide translation services and effectively ostracizing over 75 percent of the island’s population who do not speak English. In a statement after the fact, LUMA’s CEO Wayne Stensby minimized the incident, insisting that English is one of the island’s official languages. Pierluisi and his cohort have come under scrutiny for colluding with colonizers like Stensby, prioritizing the interests of foreigner corporations over the lives of Puerto Ricans themselves.

Notably, in light of Fiona, a number of former PREPA workers have volunteered their expertise to perform the grid repair work that would restore electric service to those who are still without it. Pierluisi has said he will consider their offer, but has yet to accept their help. Meanwhile, these skilled electrical workers continue to perform unrelated labor while blackouts drag on.

- In the wake of hurricanes, Puerto Ricans get pushed out

While the logical humanitarian response to hurricanes should be rapid relief for the most vulnerable, in Puerto Rico post-hurricane vulnerability has been exploited for the benefit of the rich. After María, two different visions for recovery emerged: while Puerto Ricans imagined an island rebuilt around land, energy and food sovereignty, a small group of elite foreigners saw an opportunity to cash in on disaster. Of course, the latter were abetted by Puerto Rican government officials like ex-Governor Ricardo Roselló, who in 2018 described post-María Puerto Rico as a “blank canvas” for investors and private corporations. This drive to draw in foreigners and push Puerto Ricans out is nothing new.

This drive to draw in foreigners and push Puerto Ricans out is nothing new.

In 2012, Puerto Rico’s government introduced Act 22, legislation designed to attract foreign investors to the island by offering them tax exemptions on assets like stocks and real estate. After the mass displacement caused by Maria, the government expanded these incentives with the introduction of Act 60 in 2019. Increased tax breaks coupled with record low prices on land and damaged property has ushered in a wave of capitalists looking to profit amidst a backdrop of instability and collective trauma. The incentives, enjoyed by the likes of influencer Logan Paul and crypto bro Brock Pierce, do not apply to native Puerto Ricans and have only fueled gentrification on the island, driving up housing costs, pushing people out of their homes, and deepening inequality between disenfranchised natives and wealthy outsiders. While proponents of Act 60 argue that it will infuse needed revenue into Puerto Rico’s hurting economy, the reality is that it makes it harder for working Puerto Ricans to afford to live in their own neighborhoods.

- Puerto Ricans are organizing to fight back and help one another

Disaster colonialism has created a land rush in Puerto Rico. Now more than ever, the threat of a Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans is looming. But crisis can be a catalyst for change, and Puerto Ricans find themselves at a crossroads. Time and again, Puerto Ricans have shown their commitment to fighting for a better future.

Puerto Ricans have engaged in mass demonstrations as one form of resistance. For example, in the 15 months since LUMA took over, protests demanding cancellation of the contract have not let up. Perhaps most dramatically, in 2019, leaked text messages sparked massive protests and strikes calling for the resignation of Ricardo Roselló. After only three days of mobilization, the Puerto Rican people successfully ousted him in what some called a “people’s impeachment.” Roselló’s removal, led by militant unions and the organized working masses, was an expression of Puerto Ricans’ exhaustion with the current system and of their collective power.

Faced with government inaction after María, networks of community organizations began occupying vacant buildings across the island, transforming them into hubs for relief and solidarity efforts. CAMs, which stands for Centros de Apoyo Mutuo or Mutual Aid Centers in English, are community-managed centers that serve a dual purpose — meeting the urgent material needs of those affected by disasters like Fiona, and building up consciousness around the political reality of colonialism. CAMs across the island have organized according to local needs, and as such their areas of struggle vary from one neighborhood to the next. CAM Jibaro in Lares, for example, focuses on political and practical education around agroecology, food sovereignty and traditional farming techniques. Another in Bartolo rallied local residents to repossess and renovate an abandoned school, providing shelter for families whose homes have been destroyed by hurricanes. No matter their individual struggles, all of the CAMs have a shared vision: self-sustenance and independence for Puerto Rico.

Today, Fiona — like María — has crystalized the need for total transformation in Puerto Rico. LUMA, Pierluisi, and botched relief efforts are all symptoms of a larger colonial disease that must be pulled up by the roots. In the struggle for a just recovery, Puerto Ricans need more than federal aid and isolated victories. If hurricanes in Puerto Rico teach us anything, it is that Puerto Rico needs socialism — a system that would place its poor masses ahead of profits and wealthy colonial elites, end centuries of imperial pillage, and allow Puerto Ricans to determine their own destiny free from U.S. meddling.

Not Found (#404)

Not Found (#404)

Whoops…something went wrong!

Sorry, we didn’t find the page you were looking for

Tours

Hotels

Railway tickets

Route

Countries and cities

From

Date there

Date back

Cities

Yachting

Expeditions

Dog sled tours

Snowmobile tours

Quad bike tours

Walking tours

Alloys

Bike tours

Climbing

Ski tours

Diving and snorkeling

Jeep tours

Surfing and SUP tours

Combined tours

Horse tours

Cruises

Excursion tours

Ski trips

Helicopter tours

Fishing tours

Fitness and yoga tours

Canyoning

Railway tours

Are you looking for one of the sections below?

Tours

Hotels

Railway Tickets

Routes

Attractions

We have made a selection of interesting articles for you!

Leave feedback

12345

Thank you very much 🙂

Your feedback is very important to us and will be posted on the service as soon as possible.

time!

Harm and benefit of colonialism – Power – Kommersant

60 years ago the collapse of the world colonial system began: on August 15, 1947, India gained independence. Assessing the consequences of colonialism, Vlast’ columnist Igor Fedyukin turned to scientific sources.

The first experience of decolonization was, to put it mildly, not very successful. The division of the British Indian Empire into independent India and Pakistan provoked a gigantic population exchange, accompanied by the death from exhaustion, starvation and the hands of fanatics of hundreds of thousands of people on both sides. Territorial disputes between the two wrecks of British India have not yet been settled; in India, the chaos that followed independence was stopped only after a Hindu fanatic almost killed the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi, and the eastern part, modern Bangladesh, soon broke away from Pakistan as a result of a bloody civil war.

Today, however, the results of British colonial rule in India do not look so unambiguous. It was from the British that India inherited its parliamentary system, which makes it “the largest democracy in the world.” And last but not least, due to the massive familiarity of Indians with the language of the colonialists, English, India today has become a world center for offshore programming. At the same time, however, neighboring Pakistan can boast neither stable democracy nor economic achievements. The fate of other former colonies also develops differently: among them are successful Singapore and Zimbabwe, which is now experiencing an economic catastrophe.

Thus, the question of whether colonialism benefits or harms the colonized is unlikely to have a simple and definitive answer. On the other hand, it encourages scientists to carry out a comparative study of colonial and post-colonial economies, some of the results of which seem to Vlast to be worthy of attention not only of the academic community.

To the detriment of

Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and James Robinson of the University of California at Berkeley attempted to assess the impact of colonialism based on data on the current state of political institutions and economies in 64 former colonies. Economists have suggested that the current development of these states is determined by the strategy chosen at the time by the mother country. Where climatic and epidemiological conditions were favorable, Europeans founded settlements and created stable political institutions, as, for example, in Australia or New Zealand. Where mortality was high, Europeans tried not to settle – these regions were of interest to them only as a source of minerals. Accordingly, a repressive system of government was created here, and political institutions did not develop. In addition, an economy focused on the export of natural raw materials has become an ideal basis for the formation of corrupt regimes. One of the most striking examples is the former Belgian Congo. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson believe that the system created here by the colonialists directly formed the basis of the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled the country until 1990s.

One of the most striking examples is the former Belgian Congo. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson believe that the system created here by the colonialists directly formed the basis of the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled the country until 1990s.

James Fairer and Bruce Sakerdot of Dartmouth College provide data on the demographic aspects of colonization. Scientists note that the number of the native population of Puerto Rico, whose colonization by the Spaniards began in 1505, at that time was estimated at 60 thousand people. By 1515, it was reduced to 14,400, by 1530 – to 1,500. The same thing happened in Jamaica: before the arrival of the Spaniards, tens of thousands of people lived on the island, by 1655, when it came under British rule, there were no not a single native. A shocking death rate from smallpox and other diseases was observed centuries later – during the colonization of the Pacific islands.

The results of such research seem to confirm the conclusion made by the founders of Marxism-Leninism: the imperialists mercilessly plunder the colonies, bringing lack of rights and poverty to the oppressed peoples. However, other studies paint a slightly different picture.

However, other studies paint a slightly different picture.

Benefit

The same James Fairer and Bruce Sakerdot of Dartmouth College decided to find out how the duration of colonization affects the current state of the economy of the former colonies. Scientists have compiled a database that includes 80 small islands in different seas and oceans, which at one time or another in their history were colonies of European powers. Since the islands are isolated, the researchers reasoned, other factors, such as wars with neighboring states, would not have such an influence on their current state as in the case of mainland states. Accordingly, it is the island states that provide the most accurate picture of what happens to the economy as a result of colonization.

As it turned out, on average, every extra 100 years spent as a European colony adds an additional 40% to the island’s GDP today. The same is with another important indicator that reflects the level of development of the economy and society – child mortality: the longer the island was a colony, the lower the infant mortality rate is now. The conclusion suggests itself: long-term colonization favorably affects the state of the island economy. However, this conclusion also requires, as it turns out, serious clarifications.

The conclusion suggests itself: long-term colonization favorably affects the state of the island economy. However, this conclusion also requires, as it turns out, serious clarifications.

And so and so

As research by Michael Dacosta of the International Monetary Fund shows, the duration of colonization is far from the only factor on which the well-being of former colonies depends. The scientist decided to compare Guyana and Barbados – both countries are located in the Caribbean, both were British colonies, both gained independence in 1966. Moreover, the two countries were at that moment at a very close level of socio-economic development. GDP per capita in Barbados was $469, in Guyana — $295; in both countries, the sugar industry accounted for approximately 20% of GDP; inflation was about 2% per year. The death rate in Barbados was 7.8 per 1,000 people, in Guyana it was 8.2, and the literacy rate in both countries was about 80%.

But, despite the formal similarity of starting positions, the further development of the two countries differed significantly. In 2004, GDP per capita in Barbados was $10,000, in Guyana it was ten times less. In 2003, Barbados ranked 30th out of 177 in the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) ranking for its social development, Guyana – 107th.

In 2004, GDP per capita in Barbados was $10,000, in Guyana it was ten times less. In 2003, Barbados ranked 30th out of 177 in the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) ranking for its social development, Guyana – 107th.

Dakosta explains these differences by two factors: firstly, Barbados became a British colony at the beginning of the 17th century, already in 1639 the first legislative assembly was created here, while in Guyana self-government developed much later. Accordingly, Barbados maintained an unbroken tradition of representative democracy and the transition to independence proceeded smoothly. In Guyana, on the eve of independence, inter-ethnic tensions grew, the British authorities were even forced to suspend the constitution. And then a system of so-called executive presidency developed in the country, in which the head of state was practically not controlled by anyone and could dissolve parliament at his own discretion.

Secondly, in Guyana, due to climatic conditions, the cultivation of sugar cane was carried out on large plantations. Accordingly, there were all the conditions for the formation of the proletariat and the spread of leftist views, and the plantations themselves caused the temptation of the new authorities to nationalize them. Therefore, while independent Barbados continued to develop successfully and diversify its economy, Guyana experienced a period of “cooperative socialism”, accompanied by the nationalization of the sugar industry, and then an economic recession.

Accordingly, there were all the conditions for the formation of the proletariat and the spread of leftist views, and the plantations themselves caused the temptation of the new authorities to nationalize them. Therefore, while independent Barbados continued to develop successfully and diversify its economy, Guyana experienced a period of “cooperative socialism”, accompanied by the nationalization of the sugar industry, and then an economic recession.

The legacy of the colonizers can be very heterogeneous even within the same country. Abhijit Banerjee and Lakshmi Iyer of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzed the differences in economic development in different parts of India. As scientists point out, in some cases, the colonialists retained the old feudal system, when the peasants remained under the authority of the local landowner, who was responsible for collecting taxes in the area. In other cases, the power of the landowner was abolished, taxes were collected directly by the British administrators. This system took shape over a whole century, from the middle of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century, and the choice of the form of government depended on the ideological and economic views that prevailed in England at the time the territory was annexed to the British possessions. The consequences of that choice, however, are felt to this day. As Banerjee and Ayer show, even today, 150-200 years later, in areas where the feudal system was abolished, the spread of irrigation is 25% higher, fertilizer use is 45% higher, and rice yields are 17% higher. Moreover, the literacy rate is 18% higher there, and infant mortality is 40% lower.

This system took shape over a whole century, from the middle of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century, and the choice of the form of government depended on the ideological and economic views that prevailed in England at the time the territory was annexed to the British possessions. The consequences of that choice, however, are felt to this day. As Banerjee and Ayer show, even today, 150-200 years later, in areas where the feudal system was abolished, the spread of irrigation is 25% higher, fertilizer use is 45% higher, and rice yields are 17% higher. Moreover, the literacy rate is 18% higher there, and infant mortality is 40% lower.

Thus, it turns out that the development of former colonies is influenced not so much by the duration of colonization as by the methods by which it was carried out. But this conclusion cannot be considered final.

No way

Branko Milanovic of the World Bank recently tried to figure out how the presence of democracy, colonialism and wars affected the economic growth of individual states since 1800. Quite predictably, the presence of democracy proved to be a significant contributor to economic growth, while interstate and civil wars had a very negative impact. But the most interesting thing is that no noticeable influence of colonialism was found: neither the possession of colonies, nor falling under the rule of the colonialists, had practically no effect on economic growth. It turns out that if the Europeans oppressed other countries, then no more than the local rulers did before them. No differences were found between the influence of various colonial empires (British and French).

Quite predictably, the presence of democracy proved to be a significant contributor to economic growth, while interstate and civil wars had a very negative impact. But the most interesting thing is that no noticeable influence of colonialism was found: neither the possession of colonies, nor falling under the rule of the colonialists, had practically no effect on economic growth. It turns out that if the Europeans oppressed other countries, then no more than the local rulers did before them. No differences were found between the influence of various colonial empires (British and French).

Similar results were obtained by Nicola Gennaioli of Stockholm University and Ilya Rainer of George Mason University. They showed that in those countries of Africa where by the time the Europeans arrived they already had their own political institutions, the creation of independent states subsequently proceeded much more successfully. Colonization, accordingly, did little to change the initial capacity of the colonized territory for effective state building.