Puerto rico independence from spain: The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War (Hispanic Division, Library of Congress)

Library of Congress > Researchers > Hispanic Reading Room > World of 1898 1898 HOME > Introduction

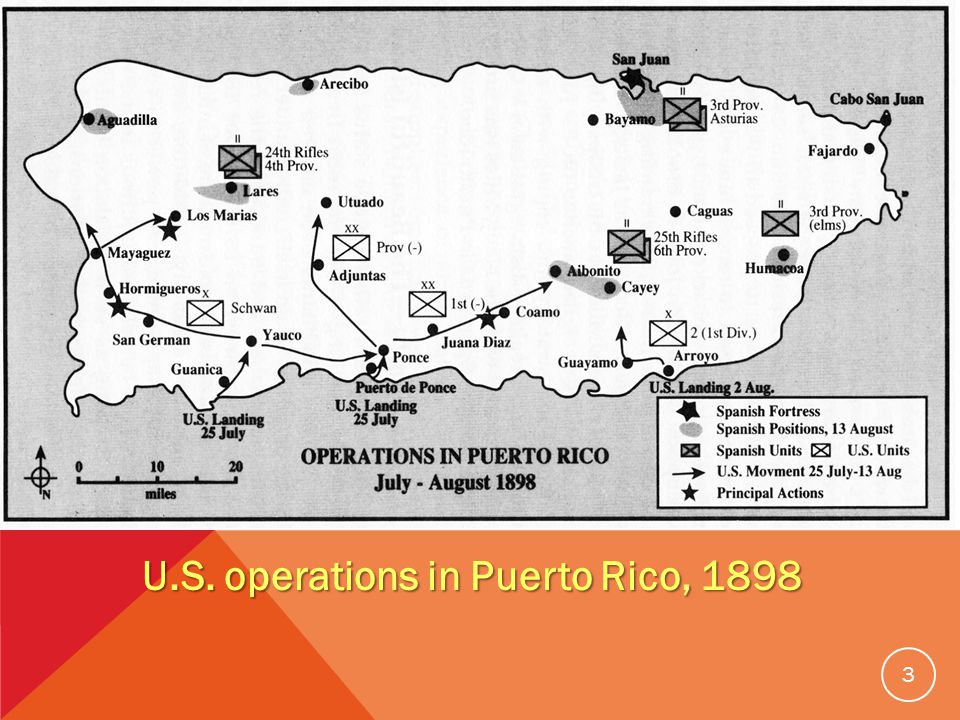

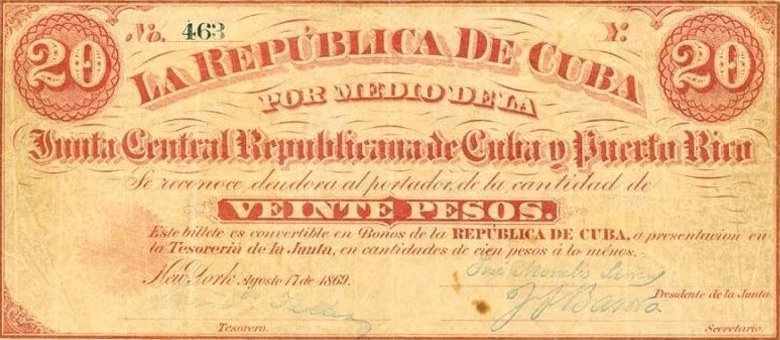

On April 25, 1898 the United States declared war on Spain following the sinking of the Battleship Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. As a result Spain lost its control over the remains of its overseas empire — Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines Islands, Guam, and other islands. BackgroundBeginning in 1492, Spain was the first European nation to sail westward across the Atlantic Ocean, explore, and colonize the Amerindian nations of the Western Hemisphere. CubaFollowing the liberation from Spain of mainland Latin America, Cuba was the first to initiate its own struggle for independence. During the years from 1868-1878, Cubans personified by guerrilla fighters known as mambises fought for autonomy from Spain. The Philippines IslandsThe Philippines too was beginning to grow restive with Spanish rule. José Rizal, a member of a wealthy mestizo family, resented that his upper mobility was limited by Spanish insistence on promoting only “pure-blooded” Spaniards. He began his political career at the University of Madrid in 1882 where he became the leader of Filipino students there. For the next ten years he traveled in Europe and wrote several novels considered seditious by Filipino and Church authorities. Puerto RicoDuring the 1880s and 1890s, Puerto Ricans developed many different political parties, some of which sought independence for the island while others, headquartered like their Cuban counterparts in New York, preferred to ally with the United States. Spain proclaimed the autonomy of Puerto Rico on November 25, 1897, although the news did not reach the island until January 1898 and a new government established on February 12, 1898. United StatesU.S. interest in purchasing Cuba had begun long before 1898. Following the Ten Years War, American sugar interests bought up large tracts of land in Cuba. Alterations in the U.S. sugar tariff favoring home-grown beet sugar helped foment the rekindling of revolutionary fervor in 1895. By that time the U.S. had more than $50 million invested in Cuba and annual trade, mostly in sugar, was worth twice that much. Fervor for war had been growing in the United States, despite President Grover Cleveland’s proclamation of neutrality on June 12, 1895. But sentiment to enter the conflict grew in the United States when General Valeriano Weyler began implementing a policy of Reconcentration that moved the population into central locations guarded by Spanish troops and placed the entire country under martial law in February 1896. By December 7, President Cleveland reversed himself declaring that the United States might intervene should Spain fail to end the crisis in Cuba. The WarFollowing its declaration of war against Spain issued on April 25, 1898, the United States added the Teller Amendment asserting that it would not attempt to exercise hegemony over Cuba. Two days later Commodore George Dewey sailed from Hong Kong with Emilio Aguinaldo on board. Fighting began in the Phillipines Islands at the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1 where Commodore George Dewey reportedly exclaimed, “You may fire when ready, Gridley,” and the Spanish fleet under Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo was destroyed. In late April, Andrew Summers Rowan made contact with Cuban General Calixto García who supplied him with maps, intelligence, and a core of rebel officers to coordinate U.S. efforts on the island. The U.S. North Atlantic Squadron left Key West for Cuba on April 22 following the frightening news that the Spanish home fleet commanded by Admiral Pascual Cervera had left Cadiz and entered Santiago, having slipped by U.S. ships commanded by William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley. War actually began for the U.S. in Cuba in June when the Marines captured Guantánamo Bay and 17,000 troops landed at Siboney and Daiquirí, east of Santiago de Cuba, the second largest city on the island. At that time Spanish troops stationed on the island included 150,000 regulars and 40,000 irregulars and volunteers while rebels inside Cuba numbered as many as 50,000. Total U.S. army strength at the time totalled 26,000, requiring the passage of the Mobilization Act of April 22 that allowed for an army of at first 125,000 volunteers (later increased to 200,000) and a regular army of 65,000. On June 22, U.S. troops landed at Daiquiri where they were joined by Calixto García and about 5,000 revolutionaries. U.S. troops attacked the San Juan heights on July 1, 1898. Dismounted troopers, including the African-American Ninth and Tenth cavalries and the Rough Riders commanded by Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt went up against Kettle Hill while the forces led by Brigadier General Jacob Kent charged up San Juan Hill and pushed Spanish troops further inland while inflicting 1,700 casualties. Representatives of Spain and the United States signed a peace treaty in Paris on December 10, 1898, which established the independence of Cuba, ceded Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States, and allowed the victorious power to purchase the Philippines Islands from Spain for $20 million. The war had cost the United States $250 million and 3,000 lives, of whom 90% had perished from infectious diseases. Back to top World of 1898 Home | Introduction | Chronology | Index | Bibliography | Literature | Maps | American Memory Library of Congress |

The Dream of Puerto Rican Independence, and the Story of Heriberto Marín

When Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, on September 20th, it

smashed into the island with withering winds of up to a hundred and

fifty-five miles per hour. The storm destroyed the island’s electric

The storm destroyed the island’s electric

power grid, wiped out eighty per cent of its agricultural crops, and

knocked out ninety-five per cent of its cell networks, along with

eighty-five per cent of its aboveground telephone and Internet cables.

Roads, bridges, and a major dam were damaged, homes were flooded and

destroyed, and thousands of people were made homeless. The economic

damage to the island was colossal, estimated to be in the range of a

hundred billion dollars. Very quickly, it was clear that Maria was the

worst natural disaster in Puerto Rico’s history. Three months later,

Puerto Ricans are still picking up the pieces. Thirty per cent of the

island remains without power. And the catastrophe only compounded the

problems of a bankruptcy and unemployment crisis that has dragged on for

several years. As soon as they could after the storm, large numbers of

Puerto Ricans—convinced that the situation will not improve—began

packing up and leaving for new lives on the U.S. mainland. As many as

As many as

two hundred thousand people out of the island’s population of 3.3

million have left so far, an exodus that shows little sign of abating.

In spite of the scale of the disaster, Puerto Rico’s authorities have

touted the storm’s extremely low death toll; as of last week, the

official count of the dead was sixty-four. President Trump picked up on

this fact early on, and used it simultaneously to defend his

Administration’s response to Maria and to minimize the storm’s

importance as an issue of concern for the rest of the country. During a

brief visit to the island, on October 3rd, Trump compared Maria’s death

toll to Hurricane Katrina’s. “Sixteen versus literally thousands of

people,” he said. “You can be very proud.” During that same trip, Trump

infamously tossed paper-towel rolls to Puerto Ricans at a

hurricane-relief shelter as if he were giving away souvenir T-shirts at

a basketball game. Earlier this month, after several

organizations—including Puerto Rico’s Center for Investigative

Journalism, the Times, and CNN—independently published findings

concluding that actually as many as a thousand and sixty-two people had

died in the storm, Ricardo Rosselló, Puerto Rico’s governor, announced

that an investigation would be undertaken to establish the true figure..jpg)

A few days after Trump’s visit, I spent a week in Puerto Rico. The

devastation was obvious. And everywhere, the sensitive subject of the

island’s relationship to the mainland as an “unincorporated U.S.

territory” was being discussed. Trump’s paper-towel-throwing appearance

had struck a nerve, and was a subject of intense media coverage. For

Puerto Ricans, the episode was a reminder, on top of Trump’s

foot-dragging and generally dismissive response to the disaster, that

they were second-class citizens.

In Utuado, a rural community in the epicenter of the island and the site

of some of Maria’s worst ravages, I spoke with a local man, Pedro J.

López,

who had lost his home in a mudslide caused by the hurricane. He was busy

trying to put his family’s life back together—he had two daughters and a

diabetic wife—and he made it plain that he was doing so with pride, and

was not waiting for any handouts. But he also told me that he had heard

about Trump’s visit, and he wondered aloud whether the American

President expected Puerto Ricans to use those paper towels to wipe “our

asses or our tears?”

Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States is an unequal one, and

it has over the years brought about many humiliations for Puerto

Ricans—who are U. S. citizens but who cannot vote for President if they

S. citizens but who cannot vote for President if they

live on the island, and have limited representation in Congress. Yet in

modern times, most American Presidents have taken pains to be respectful

of the island and its status. Not so with Trump. San Juan’s outspoken

mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, who repeatedly tangled with the President on

Twitter and through the media in the immediate aftermath of the storm,

told me that he was “a man with a big mouth” who “lacked empathy.” But

she hoped that the political fallout from Hurricane Maria would provide

an opportunity to finally redefine Puerto Rico’s relationship with the

United States, which, she said, “needs to be dignified. It has to

change.”

Puerto Rico was claimed for Spain five hundred years ago, and its first

governor was Juan Ponce de León. Beginning in the nineteenth century,

the island’s residents began jostling for greater freedoms. Inspired by

the liberal reforms espoused by the French Revolution and by Simón

Bolívar’s battles for independence around the hemisphere, a Puerto Rican

nationalist movement was born. Beginning in 1868, these nationalists

Beginning in 1868, these nationalists

launched a series of revolts that were abortive but persistent enough to

convince Spain’s government, in early 1898, to grant the island a

measure of autonomy. Yet just a few months later, following the brief

but decisive Spanish-American War, the island was claimed as booty by

the United States. Something similar happened in neighboring Cuba, where

local patriots had fought the Spaniards at great human cost for most of

the preceding four decades, only to be similarly “freed” by the

Americans, who promptly put them under military rule. The two islands,

which the Puerto Rican poet Lola Rodríguez del Tió famously called “two

wings of the same bird,” were Spain’s last colonies in the Americas, and

in the course of one summer, both fell under U.S. control. In 1902, Cuba

was granted its independence in exchange for, among other concessions,

tolerating the U.S. naval base at Guantámano Bay. Puerto Rico’s day

never came.

In 1914, Puerto Rico’s nominal Congress—operating under U. S.

S.

jurisdiction—unanimously voted for Puerto Rico’s independence, but the

gesture was ignored. Instead, in 1917, citizenship was imposed on Puerto

Ricans, and the island was given an American governor appointed by

Washington. The move polarized the Puerto Rican political scene,

splitting its parties into those that sought independence, those that

sought statehood, and those that sought a better deal with the mainland.

(More or less the same splits persist among Puerto Ricans today: a

little over half of Puerto Ricans now support full U.S. statehood; about

a quarter like the status quo—Puerto Rico as an “associated sovereign

country,” as defined in its formal agreement with the U.S.; only about

fifteen per cent wish for greater autonomy or outright independence.)

American sugar interests increasingly began to dominate the Puerto Rican

economy. Puerto Rico’s ports, utilities, and railroads were also

American-owned. In the nineteen-thirties, after security forces

repeatedly used lethal violence to quell demonstrations by Puerto Rican

nationalists, some opted for armed struggle, and they launched a

campaign of assassinations and other violent attacks against government

officials and security forces.

The leader of the independence movement, Pedro Albizu Campos, was a

Harvard Law graduate, a polymath, and a gifted public speaker. He

adopted the goal of Puerto Rican independence as his life’s purpose

under the slogan, “the homeland is valor and sacrifice.” As the leader

of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, he organized a militarily trained

youth wing called Los Cadetes de la República, with the idea that

these young “soldiers” would eventually lead the armed struggle for the

country’s independence. In 1936, after two cadets assassinated a

notorious police official and were in turn caught and executed, Albizu

Campos and several cohorts were arrested and found guilty of sedition.

Albizu Campos spent most of the next decade in U.S. prisons. He was

freed and returned to Puerto Rico in 1947, just before the island’s

first-ever free gubernatorial elections were held.

The politician who won them, Luis Muñoz Marín, was Albizu Campos’s total

opposite. He not only opposed Puerto Rico’s independence but was also a

driving force behind a move to keep the island within the American orbit

as an “unincorporated U. S. territory.” Seen as a pro-U.S. bulwark

S. territory.” Seen as a pro-U.S. bulwark

against the rise of Communism in the hemisphere, Muñoz Marín became a

darling of successive American Administrations. During the first nine

years of the sixteen he would spend in power, Muñoz Marín benefitted

from La Ley de la Mordaza, or the Gag Law, which allowed him to jail

anyone who publicly espoused pro-independence beliefs. Huge numbers of

Puerto Ricans were placed under long-term surveillance by secret police,

and thousands were arrested for their political beliefs. The Puerto

Rican flag was outlawed.

On October 27, 1950, after being alerted to preëmptive police raids

being carried out against his followers, Albizu Campos summoned his

followers to arms. His small band of nationalists retrieved secretly

cached weapons and rose up to seize towns and attack police stations and

other targets. In Jayuya, a small town at the mountainous center of the

island, the nacionalistas seized the police station after a

shootout—one policeman died—and also burned down the town’s U. S. post

S. post

office. The local rebel leader, a woman named Blanca Canales, raised

Puerto Rico’s flag in the town square and declared a “free republic of

Puerto Rico.” In nearby Utuado—one of the townships most heavily damaged

by Hurricane Maria—at least nine nationalists were killed,

five of them summarily executed after surrendering to authorities. Muñoz

Marín secured both towns after ordering them to be pounded by field

artillery and strafed from the air. In Old San Juan, four more rebels

were killed in an abortive attack on the governor’s residence, La

Fortaleza.

On the island, the rebellion was over by the night of October 31st. But

the plot wasn’t finished. On the morning of November 1st, in Washington

D.C., two Puerto Rican nationalists approached Blair House, where

President Harry Truman was staying temporarily during renovations to the

White House across the street, and opened fire on the security men

guarding the building. Their plan was to enter Blair House and kill

Truman, if they could. They never got inside the building. Instead, in

They never got inside the building. Instead, in

the shootout, one of the Puerto Ricans died, and so did a Secret Service

agent. Truman himself was unhurt. Albizu Campos, who was arrested along

with several dozen of his followers, was sentenced to eighty years in

prison. Two years later, Puerto Rico’s status as an unincorporated U.S.

territory, or “commonwealth,” was voted on and overwhelmingly approved

by Congress. In 1954, in an effort to keep the cause of Puerto Rican

independence visible, four more of Albizu Campos’s followers entered the

U.S. Capitol and opened fire on congressmen there, wounding five of them

before being overwhelmed by police. Albizu Campos, who had received a

pardon a few months earlier, was immediately rearrested and spent

another decade in prison before his death, in April, 1965.

One of Albizu Campos’s soldiers is still alive. His name is Heriberto

Marín, and he was a proud Cadete de la República, just shy of his

twenty-first birthday when he participated in the Jayuya uprising. A

A

trim, mustachioed man with white hair, Marín is now eighty-nine but

appears a decade younger. He lives in a tidy second-floor apartment

overlooking San Juan’s colonial-era Spanish arsenal and the harbor. On

the day that I visited him, in October, a red-white-and-blue Puerto Rican

flag was hanging from his balcony, and a U.S. naval ship making a port

call was visible in the distance. The apartment was decorated with

nationalist memorabilia. A black-and-white photograph of Pedro Albizu

Campos hung on a wall in the living room.

When I asked him about the 1950 uprising, Marín gave a polite smile. “It

was the era of decolonization, the spirit of the times,” he began. “It

was David against Goliath. Dr. Albizu Campos told us we might die, but

that we might also succeed.” Their plan had not merely been to fight the

police in Jayuya, he explained, but to seize the police’s guns and then

make their way to nearby Utuado, where they were to meet up with other

rebel units and make a final stand. Albizu Campo had expected the U.S.

Albizu Campo had expected the U.S.

military to become directly involved, and once they did, “we would have

let the world know about Puerto Rico.”

Marín (who is of no relation to Luis Muñoz Marín) had special words of

praise for Blanca Canales, the leader of the Jayuya uprising. Canales

had been a member of a local landowner family, yet she’d taken the risk

of hiding the rebels’ weapons in her home. “Women have always played a

special role in the independence struggle for Puerto Rico,” he said.

“Dr. Albizu Campos had a saying: ‘When men’s trousers fall down, the

women will raise the flag aloft.’ ”

Marín was born in Jayuya, to a family of poor tenant farmers who worked

for the Canaleses. The Maríns had been given a patch of land to farm,

and his mother cooked for the Canaleses. As Marín told it, the Canaleses

were different from other landowners. “In return for our piece of land,

we were supposed to give some of our harvest to the Canaleses, but they

never asked us for anything,” he said. The Canaleses were also

The Canaleses were also

nationalists. As a boy in 1937, he had been in their home and witnessed

members of the family weeping after the news of an infamous police

massacre of nationalists in the city of Ponce. The episode affected him

deeply. “By the age of fourteen, I was a nationalist,” he said.

During the 1950 uprising, Marín told me, he had had the “immense honor”

of helping Blanca Canales raise the Puerto Rican flag in Jayuya’s town

square. When the fighting was over, he was sentenced to a hundred and

fifty-four years in prison. He was sent first to La Princesa, an ancient

prison in Old San Juan. He waved out the window, to the nearby buildings

of the old town, and explained that the old jail had been shut down and

eventually remodelled. “They turned it into a palace to erase the memory

of all the crimes that had been committed there,” he said. “It’s now the

Puerto Rican tourism office.” After his time in La Princesa, he’d been

sent on to another prison known as El Oso Blanco, the White Bear, where

Albizu Campos was also held. Marín lamented that it, too, was no longer

Marín lamented that it, too, was no longer

in existence, having been torn down in spite of a campaign by himself

and other former prisoners to preserve it for posterity. “There is no

historical consciousness here,” he said.

Marin spent eight years in Oso Blanco in a six-by-nine-foot cell. A year

and a half was spent in total isolation. The rest of the time he shared

the cell with a fellow nacionalista. His memories were not all

aggrieved ones. He spoke highly of the prison’s medical director, who

was a Spanish Republican exile, said to be related to the late Spanish

poet Federico García Lorca. Marín credited the director for acts of

kindness toward Albizu Campos, whom authorities had consigned, as a kind

of punishment, to Oso Blanco’s tuberculosis ward. Marín choked up,

recalling how he had once been allowed a brief visit with Albizu Campos,

and found him bedridden and ill, and how they had hugged one another and

wept. It was the last time he ever saw him.

Marín got up and walked over to a side table where there was a

black-and-white photograph of a young woman. He brought it back and held

He brought it back and held

it on his lap. It was his late wife, Cándida. She had died three years

ago. They had met as teen-agers in high school. She had shared his

passion for Puerto Rican independence, and they had fallen in love. Then

had come the uprising and his long incarceration. After he got out,

freed in an amnesty, Marín spotted her at a social occasion. “My heart

did a tsunami,” he said. “I asked her if she was married. She said, ‘How

could I, since I was waiting for you?’ ” Marín smiled at the memory of

the moment. They were married fifty-four years, and had four children

together.

How referendums on self-determination were held in some countries

September 23, 2022, 08:10

Voting on entry into the Russian Federation

TASS-DOSIER. On September 23-27, in the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, as well as in the liberated territories of the Kherson and Zaporozhye regions, referendums on joining the Russian Federation will be held.

About how referendums on self-determination were held in some countries – in the TASS material.

Puerto Rico (1967, 1993, 1998, 2012, 2017, 2020)

The island of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean has been a freely associated state with the US since 1952, meaning that it is administered by the US but is not an integral part of that state. Since the 1960s, the idea of joining the United States as a state began to gain popularity among the population of Puerto Rico. The issue of the status of the island was discussed during six plebiscites, in which the inhabitants of the island were asked to choose from three options: securing their current status, joining the United States as a state, or gaining independence. At 19In 1967, 60.4% of those who voted in favor of maintaining the status of an associated state, in 1993 and 1998 – 48.9% and 50.5%. In 2012, the idea of joining the United States as a state was supported by 61.2% of Puerto Ricans, in 2017 their share reached 97%, in 2020 it dropped to 52% (the proposal for the island’s full independence gained less than 5% of the votes in plebiscites). However, referendums are advisory in nature. In the United States, the Republican Party opposes the annexation of the island, which blocks the adoption of a corresponding decision by Congress. According to experts, Washington refuses to give Puerto Rico the status of a state because of the financial crisis on the island, since if it enters, the United States will have to completely take over the economic problems of this territory.

However, referendums are advisory in nature. In the United States, the Republican Party opposes the annexation of the island, which blocks the adoption of a corresponding decision by Congress. According to experts, Washington refuses to give Puerto Rico the status of a state because of the financial crisis on the island, since if it enters, the United States will have to completely take over the economic problems of this territory.

Kosovo (Serbia; 1991)

Kosovo in 1945 received the status of an autonomous region within Serbia (occupies an area of 10.9 thousand square kilometers, approximately 12% of the territory of Serbia), which was part of Yugoslavia as one of the six republics, in 1963 – the status of an autonomous region (also part of Serbia). In 1974, the region was granted broad powers, with the exception of the right to secede from Yugoslavia. In 1981, the first major nationalist protests of Kosovo Albanians took place, demanding the transformation of the region into a republic within Yugoslavia. On September 19For 91 years, they organized a referendum, 99% of the participants of which were in favor of secession from Serbia and Yugoslavia. Turnout was 87%, but the referendum was boycotted by Serbs living in Kosovo and not recognized by Belgrade. On September 22, 1991, the Kosovo Albanians declared the independence of the region, then only Albania recognized it. In 1998, the conflict between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs escalated into bloody armed clashes, to stop which Belgrade sent army units to Kosovo. Western countries accused the Serbs of the genocide of the Albanian population, and in March – June 19In 99, NATO members, without the sanction of the UN Security Council, carried out a military operation against Yugoslavia, which resulted in the withdrawal of Yugoslav troops from Kosovo and the flight of the Serbian population (more than 200 thousand Serbs left the region).

On September 19For 91 years, they organized a referendum, 99% of the participants of which were in favor of secession from Serbia and Yugoslavia. Turnout was 87%, but the referendum was boycotted by Serbs living in Kosovo and not recognized by Belgrade. On September 22, 1991, the Kosovo Albanians declared the independence of the region, then only Albania recognized it. In 1998, the conflict between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs escalated into bloody armed clashes, to stop which Belgrade sent army units to Kosovo. Western countries accused the Serbs of the genocide of the Albanian population, and in March – June 19In 99, NATO members, without the sanction of the UN Security Council, carried out a military operation against Yugoslavia, which resulted in the withdrawal of Yugoslav troops from Kosovo and the flight of the Serbian population (more than 200 thousand Serbs left the region).

In June 1999, UN international civilian forces and international security forces under the auspices of NATO (KFOR) entered Kosovo. From that time on, the region began to be controlled by the UN Transitional Administration. Despite the fact that UN Security Council Resolution 1244 of 1999 speaks of maintaining the territorial integrity of Serbia, in 2007 the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General in Kosovo Martti Ahtisaari developed a document that, in fact, became a plan for separating the region. On February 17, 2008, the Kosovo Parliament unilaterally declared the province’s independence from Serbia. Today the Republic of Kosovo is recognized by more than 90 out of 193 member countries of the UN. Serbia continues to consider Kosovo its autonomous province. Russia adheres to the same position regarding Kosovo.

From that time on, the region began to be controlled by the UN Transitional Administration. Despite the fact that UN Security Council Resolution 1244 of 1999 speaks of maintaining the territorial integrity of Serbia, in 2007 the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General in Kosovo Martti Ahtisaari developed a document that, in fact, became a plan for separating the region. On February 17, 2008, the Kosovo Parliament unilaterally declared the province’s independence from Serbia. Today the Republic of Kosovo is recognized by more than 90 out of 193 member countries of the UN. Serbia continues to consider Kosovo its autonomous province. Russia adheres to the same position regarding Kosovo.

East Timor (1999)

East Timor occupies the eastern part of the Timor Island in Southeast Asia, an area of 15 thousand square meters. km. In 1975, he declared independence from Portugal and in the same year was occupied by Indonesia, whose rule lasted 24 years. During this time, the resistance of the Indonesian army was provided by detachments of the Revolutionary Front for an independent East Timor (Fretilin). From 100 to 200 thousand people became victims of the war and mass repressions (the population was about 600 thousand).

From 100 to 200 thousand people became victims of the war and mass repressions (the population was about 600 thousand).

In January 1999, Indonesia granted East Timor broad autonomy and the right to hold a referendum on self-determination. It was organized on August 30, 1999. Two questions were put to the vote: “Do you accept special autonomy for East Timor within the unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia?” and “Do you reject the proposed special autonomy for East Timor leading to secession from Indonesia?”. More than 90% of registered voters took part in the referendum, 78.5% of them voted for independence. Following the announcement of the voting results, another outbreak of violence (provoked by supporters of keeping the territory as part of Indonesia) followed, which was stopped only after the introduction of an international peacekeeping contingent. Indonesia recognizes referendum results 19October, after which her troops left East Timor. On October 25, 1999, the UN Security Council established the East Timor Transitional Administration (as an integrated peacekeeping operation), which was given responsibility for the administration of the territory during its transition to independence. East Timor was officially declared an independent state on May 20, 2002.

East Timor was officially declared an independent state on May 20, 2002.

Tokelau (New Zealand; 2006, 2007)

Tokelau – non-self-governing territory of New Zealand in the Pacific Ocean with a population of 1.5 thousand people; occupies three islands with a total area of 10 sq. km. Referendums were held on February 11, 2006 and October 20-24, 2007, in which a proposal for self-determination in the form of free association with New Zealand was submitted. In 2006, 60% of the referendum participants voted for the association, in 2007 – 64.5%, but this was not enough to gain the necessary two-thirds of the votes (66%). Thus, Tokelau retained its former status as a Non-Self-Governing Territory.

Transylvania (Romania; 2007)

About 1.2 million Hungarians (6.5% of the country’s population) live in Romania, half of whom belong to the Székely sub-ethnic group. Most of the Székelys live compactly in the north-west of the country in the administrative regions of Harghita, Covasna and Mures (counties), belonging to the historical region of Transylvania. The Szekely National Union, established by them in 2003, repeatedly tried to hold a referendum on the creation of the Szekely autonomy in Romania. However, bills for such a vote were rejected by the Romanian parliament without discussion. In 2007, an informal referendum was organized in three Transylvanian counties, during which 99% of its participants supported the introduction of self-government. In 2009 and 2010, congresses of representatives of local authorities were held, at which the creation of the Szekely autonomy was proclaimed, the anthem, flag, coat of arms and administrative map were approved. The congresses also put forward a demand to give the Hungarian language official status at the regional level. The central authorities of Romania did not recognize the results of the referendum and the decisions of the congresses.

The Szekely National Union, established by them in 2003, repeatedly tried to hold a referendum on the creation of the Szekely autonomy in Romania. However, bills for such a vote were rejected by the Romanian parliament without discussion. In 2007, an informal referendum was organized in three Transylvanian counties, during which 99% of its participants supported the introduction of self-government. In 2009 and 2010, congresses of representatives of local authorities were held, at which the creation of the Szekely autonomy was proclaimed, the anthem, flag, coat of arms and administrative map were approved. The congresses also put forward a demand to give the Hungarian language official status at the regional level. The central authorities of Romania did not recognize the results of the referendum and the decisions of the congresses.

South Sudan (2011)

Even during the period of British occupation, Sudan was actually divided into an Arab-Muslim north and an African-Christian south. After Sudan gained independence in 19In 56, the contradictions between the north and the south escalated due to the violent Islamization carried out by the authorities in the southern regions of the country. The country experienced two protracted civil wars (1956-1972 and 1983-2005). Following the results of the first war, the southern regions (644,000 sq. km) received the status of autonomy, following the results of the second – the right to hold a referendum on the issue of further status. The plebiscite took place on January 9-15, 2011 with a turnout of 97%, 98.8% of its participants voted for the independence of South Sudan (the population at that time was about 10 million). The Sudanese authorities recognized its results. 9On July 2011, the creation of a new state was proclaimed – the Republic of South Sudan, on July 14 it became the 193rd member of the UN.

After Sudan gained independence in 19In 56, the contradictions between the north and the south escalated due to the violent Islamization carried out by the authorities in the southern regions of the country. The country experienced two protracted civil wars (1956-1972 and 1983-2005). Following the results of the first war, the southern regions (644,000 sq. km) received the status of autonomy, following the results of the second – the right to hold a referendum on the issue of further status. The plebiscite took place on January 9-15, 2011 with a turnout of 97%, 98.8% of its participants voted for the independence of South Sudan (the population at that time was about 10 million). The Sudanese authorities recognized its results. 9On July 2011, the creation of a new state was proclaimed – the Republic of South Sudan, on July 14 it became the 193rd member of the UN.

Southern Region of Brazil (2016 and 2017)

Southern Region of Brazil includes the federal districts of Rio Grande do Sul, Parana and Santa Catarina, with a total area of 576. 7 thousand square meters. km with a population of 30.6 million people, which is approximately 6.7% and 14.3% of the territory and population of Brazil. The contribution of the region to the country’s GDP is about 16%, but residents are not satisfied that their income goes to other areas. In 2016 and 2017, referendums were organized in the Southern region, 616 thousand and 341.5 thousand respectively (out of 21 million registered voters) took part in them. The question was put to the vote: “Do you want Rio Grande do Sul, Parana and Santa Catarina to form an independent country?”. Both times over 95% of the vote was cast in favor of secession, but the Brazilian government did not recognize the results of the referendums.

7 thousand square meters. km with a population of 30.6 million people, which is approximately 6.7% and 14.3% of the territory and population of Brazil. The contribution of the region to the country’s GDP is about 16%, but residents are not satisfied that their income goes to other areas. In 2016 and 2017, referendums were organized in the Southern region, 616 thousand and 341.5 thousand respectively (out of 21 million registered voters) took part in them. The question was put to the vote: “Do you want Rio Grande do Sul, Parana and Santa Catarina to form an independent country?”. Both times over 95% of the vote was cast in favor of secession, but the Brazilian government did not recognize the results of the referendums.

Scotland (UK; 2014)

Scotland, covering an area of 78.7 thousand sq. km (32% of the UK) with a population of 5.3 million people (approx. 8% of the population), is part of the United Kingdom with broad autonomy. However, there have always been political forces advocating complete independence. On September 18, 2014, after long consultations with the British government, a referendum was held in Scotland on secession from the UK, but the majority of voters (55.3%) expressed their desire to remain part of the kingdom. Again, the question of independence arose after the referendum in the UK on June 23, 2016, in which 52% of its participants voted for the country’s exit from the European Union. At the same time, in Scotland, 62% of the population were in favor of maintaining the UK’s membership in the EU. This circumstance gave rise to Scottish nationalists to promote the idea of a new independence referendum. In June 2022, the Scottish National Party, which has a majority in the regional parliament, launched a campaign for a consultative referendum 19October 2023, Official London consistently states that it is not going to give Edinburgh such a right, believing that the Scots have already made their choice in 2014.

On September 18, 2014, after long consultations with the British government, a referendum was held in Scotland on secession from the UK, but the majority of voters (55.3%) expressed their desire to remain part of the kingdom. Again, the question of independence arose after the referendum in the UK on June 23, 2016, in which 52% of its participants voted for the country’s exit from the European Union. At the same time, in Scotland, 62% of the population were in favor of maintaining the UK’s membership in the EU. This circumstance gave rise to Scottish nationalists to promote the idea of a new independence referendum. In June 2022, the Scottish National Party, which has a majority in the regional parliament, launched a campaign for a consultative referendum 19October 2023, Official London consistently states that it is not going to give Edinburgh such a right, believing that the Scots have already made their choice in 2014.

Catalonia (Spain; 2017)

Catalonia is an autonomous region in Spain, covering an area of 32. 1 thousand square meters. km (6.3% of the country’s territory) the population is 7.5 million people (16% of the population of Spain). The desire for independence is associated with both cultural and linguistic, as well as economic reasons, in particular, supporters of secession believe that Catalonia “feeds Spain” (the share of autonomy in the country’s GDP is 19%). In 2009-2010, a series of informal consultative referendums were held in the region, during which 90% of the participants voted for sovereignty. On November 9, 2014, a poll of citizens was conducted in Catalonia, in which more than 80.76% of respondents spoke in favor of independence (37% of the inhabitants of the region participated). On October 1, 2017, a referendum was held in the autonomous community, where citizens were asked to answer the question: “Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state with a republican form of government?”. 9 voted for independence0% of voters (turnout – 43%). However, its results were not recognized by the Spanish government, since the country’s constitution lacks articles that allow autonomous regions to hold such referendums without the consent of the central government and declare independence unilaterally.

1 thousand square meters. km (6.3% of the country’s territory) the population is 7.5 million people (16% of the population of Spain). The desire for independence is associated with both cultural and linguistic, as well as economic reasons, in particular, supporters of secession believe that Catalonia “feeds Spain” (the share of autonomy in the country’s GDP is 19%). In 2009-2010, a series of informal consultative referendums were held in the region, during which 90% of the participants voted for sovereignty. On November 9, 2014, a poll of citizens was conducted in Catalonia, in which more than 80.76% of respondents spoke in favor of independence (37% of the inhabitants of the region participated). On October 1, 2017, a referendum was held in the autonomous community, where citizens were asked to answer the question: “Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state with a republican form of government?”. 9 voted for independence0% of voters (turnout – 43%). However, its results were not recognized by the Spanish government, since the country’s constitution lacks articles that allow autonomous regions to hold such referendums without the consent of the central government and declare independence unilaterally. After Catalonia declared independence on October 27, the Spanish government introduced direct rule in this region, it lasted five months, until new parliamentary elections were held in the autonomy.

After Catalonia declared independence on October 27, the Spanish government introduced direct rule in this region, it lasted five months, until new parliamentary elections were held in the autonomy.

Iraqi Kurdistan (2017)

Iraqi Kurdistan is an area of ethnic settlement of Kurds in the north and northeast of Iraq. Its area is 40.643 thousand square meters. km. (9.3% of the country’s territory), the population is more than 5 million people (12%). It has the status of autonomy (off. – Kurdish Autonomous Region; KAR). In 2014, an informal poll was conducted in the CAR, more than 80% of the participants were in favor of independence. On September 25, 2017, the authorities of the autonomous region organized a referendum, during which, with a turnout of 72%, 9 voted for independence2.73% of voters. The Iraqi government did not recognize its results. The holding of the plebiscite led to a military clash, as a result, federal forces occupied about 40% of the Kurdish territory, including the oil province of Kirkuk. In order to reduce the escalation of the conflict, the CAR authorities proposed to “freeze” the results of the referendum. In November 2017, the Supreme Federal Court of Iraq ruled that the basic law of the country does not contain an article allowing the separation of any region, and excluded the secession of the Kurdish autonomy from the republic. The authorities of the CAR said they respect the decision of the court.

In order to reduce the escalation of the conflict, the CAR authorities proposed to “freeze” the results of the referendum. In November 2017, the Supreme Federal Court of Iraq ruled that the basic law of the country does not contain an article allowing the separation of any region, and excluded the secession of the Kurdish autonomy from the republic. The authorities of the CAR said they respect the decision of the court.

Bougainville (Papua New Guinea; 2019)

Bougainville is a region of Papua New Guinea, which includes a number of islands, the largest of which is Bougainville (the area of the region is approximately 9.4 thousand sq. km, or 2% of territory of the country, population – 250 thousand in 2011). Separatist sentiments are traditionally strong here. Since 1988, supporters of independence have waged an armed struggle against the government army. The confrontation, during which about 20 thousand people were killed, ended at 1998 peace negotiations. In 2001, the region received broad autonomy. Then the country’s government promised to hold a referendum on the future political status of the autonomy within 10-15 years. The referendum was held in November – December 2019 with an 85% turnout. The question was put to the vote: “Do you agree that Bougainville should have: (1) greater autonomy; (2) independence?”. 97% of voters were in favor of secession from Papua New Guinea. It is assumed that the region will be able to gain independence by 2027.

Then the country’s government promised to hold a referendum on the future political status of the autonomy within 10-15 years. The referendum was held in November – December 2019 with an 85% turnout. The question was put to the vote: “Do you agree that Bougainville should have: (1) greater autonomy; (2) independence?”. 97% of voters were in favor of secession from Papua New Guinea. It is assumed that the region will be able to gain independence by 2027.

New Caledonia (France, 2018, 2020, 2021)

New Caledonia is a special administrative-territorial unit of France on the island of the same name and a group of small islands in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, in Melanesia. Territory – 19 thousand square meters. km, the population is about 275 thousand people. In accordance with the agreement (Matignon) signed in June 1988 by the French government and representatives of the NC, over a ten-year period, France gradually transferred important issues of self-government to the local authorities. Upon its completion at 19In 1998, a referendum on self-determination was supposed to be held. However, in May 1998, a new agreement (Numea) was concluded, which granted NK the status of an overseas entity and determined the procedure for the gradual transfer of full control over all spheres of NK’s life to the local administration, only defense, justice, internal security and currency issues remained in Paris’ jurisdiction. The referendum took place on November 4, 2018. Most of its participants opposed secession from France (56.4% with a turnout of over 80%). On October 4, 2020 and December 12, 2021, two more referendums were held, in which the majority again voted in favor of maintaining the status quo (53.26% with a turnout of 85.64% and

Upon its completion at 19In 1998, a referendum on self-determination was supposed to be held. However, in May 1998, a new agreement (Numea) was concluded, which granted NK the status of an overseas entity and determined the procedure for the gradual transfer of full control over all spheres of NK’s life to the local administration, only defense, justice, internal security and currency issues remained in Paris’ jurisdiction. The referendum took place on November 4, 2018. Most of its participants opposed secession from France (56.4% with a turnout of over 80%). On October 4, 2020 and December 12, 2021, two more referendums were held, in which the majority again voted in favor of maintaining the status quo (53.26% with a turnout of 85.64% and

The Government of the Basque Country in Spain decided to hold an independence referendum along the lines of Puerto Rico

MADRID, 27 September. /Correspondent of RIA “Novosti” Juan Cobo/. According to the correspondent of RIA Novosti, the head of the government of the autonomous region of the Basque Country, Juan Jose . .. RIA Novosti, 27.09.2002 :06

.. RIA Novosti, 27.09.2002 :06

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/sharing/article/233349.jpg?1212667592

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

2 926

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA “Russia Today”

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn-p1ai/Awards/

2002

RIA

1

5

4.7 4000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 4

96

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

ABOUT/COPYRIGHT.HTML

https: //xn—c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

9000

4

49000 645-6601

FSUE MIA Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

RIA Novosti

1,000 .xn-p1ai/ awards/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4. 7

7

9000

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA “Russia Today”

2222 https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

politics, worldwide

politics, global

MADRID, 27 September. /Correspondent of RIA “Novosti” Juan Cobo/.

The government of the Basque Country decided to hold a referendum, asking its

citizens such a variant of relations with the rest of Spain, which exists between

Puerto Rico and USA.

According to RIA Novosti correspondent, Juan José Ibarretche, the head of the government of the autonomous region of the Basque Country, announced on Friday in the autonomous parliament that the executive branch had decided to hold a referendum to decide whether to keep the current status of this region or accept a new one.

Ibarretche is in favor of the recognition of the Basque Country as a “Basque state with its own national identity”, which will be represented in international organizations and have its own judiciary. He and his supporters are offered a formula of “free association of the Basques with the Spanish multinational state” /there is a precedent for such a status in Puerto Rico, which is a state freely associated with the United States/. Such a status, if approved in a referendum, according to the authors’ intention, will allow the Basques to develop an acceptable formula for them of “free and voluntary joint sovereignty” shared with Spain.

He and his supporters are offered a formula of “free association of the Basques with the Spanish multinational state” /there is a precedent for such a status in Puerto Rico, which is a state freely associated with the United States/. Such a status, if approved in a referendum, according to the authors’ intention, will allow the Basques to develop an acceptable formula for them of “free and voluntary joint sovereignty” shared with Spain.

The head of the Basque Autonomous Government considers that such a process is legal and fits into the framework of additional articles to the Spanish Constitution and the Statute of Autonomy, which state that the consent to autonomy within the Spanish state “does not mean the renunciation of the Basque people from their rights, which they must be inherent in its history.”

The central government of Spain categorically opposes such a referendum, regarding it as a separatist initiative.

Juan José Ibarretche also announced that he was unilaterally assuming those administrative rights and powers, the gradual transfer of which had long been provided for in the Statute of Autonomy, but, as many Basques believe, was being delayed in every way by the central government of Madrid. The fact is that the Madrid authorities do not trust the moderate nationalists ruling in the Ibarretx government, accusing them of deliberately or unintentionally playing along with the ETA terrorists.

The fact is that the Madrid authorities do not trust the moderate nationalists ruling in the Ibarretx government, accusing them of deliberately or unintentionally playing along with the ETA terrorists.

Meanwhile, all three provinces of the Basque Country are filled with banners and posters demanding independence and ETA toasts. They call the militants “soldiers of the motherland.” One of them, who died from the explosion of his own bomb, was declared an “honorary citizen” by his native city, for which the prosecutor’s office is going to bring those responsible on charges of “apologia for terrorism.” Members of the outlawed and ETA-affiliated Batasuna party constantly hold demonstrations and protests, although the Ibarretche government bans them because they are ordered and held without permission. These manifestations of disobedience on the part of the radicals are also directed against the government of Ibarretche, which they consider excessively moderate, and therefore “compromising”.

That war concluded with a treaty that was never enforced. In the 1890’s Cubans began to agitate once again for their freedom from Spain. The moral leader of this struggle was José Martí, known as “El Apóstol,” who established the Cuban Revolutionary Party on January 5, 1892 in the United States. Following the grito de Baire, the call to arms on February 24, 1895, Martí returned to Cuba and participated in the first weeks of armed struggle when he was killed on May 19, 1895.

That war concluded with a treaty that was never enforced. In the 1890’s Cubans began to agitate once again for their freedom from Spain. The moral leader of this struggle was José Martí, known as “El Apóstol,” who established the Cuban Revolutionary Party on January 5, 1892 in the United States. Following the grito de Baire, the call to arms on February 24, 1895, Martí returned to Cuba and participated in the first weeks of armed struggle when he was killed on May 19, 1895. He returned to Manila in 1892 and founded the Liga Filipina, a political group dedicated to peaceful change. He was rapidly exiled to Mindanao. During his absence, Andrés Bonifacio founded Katipunan, dedicated to the violent overthrow of Spanish rule. On August 26, 1896, after learning that the Katipunan had been betrayed, Bonifacio issued the Grito de Balintawak, a call for Filipinos to revolt. Bonifacio was succeeded as head of the Philippine revolution by Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy, who had his predecessor arrested and executed on May 10, 1897. Aguinaldo negotiated a deal with the Spaniards who exiled him to Hong Kong with 400,000 pesos that he subsequently used to buy weapons to resume the fight.

He returned to Manila in 1892 and founded the Liga Filipina, a political group dedicated to peaceful change. He was rapidly exiled to Mindanao. During his absence, Andrés Bonifacio founded Katipunan, dedicated to the violent overthrow of Spanish rule. On August 26, 1896, after learning that the Katipunan had been betrayed, Bonifacio issued the Grito de Balintawak, a call for Filipinos to revolt. Bonifacio was succeeded as head of the Philippine revolution by Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy, who had his predecessor arrested and executed on May 10, 1897. Aguinaldo negotiated a deal with the Spaniards who exiled him to Hong Kong with 400,000 pesos that he subsequently used to buy weapons to resume the fight.

President William McKinley, inaugurated on March 4, 1897, was even more anxious to become involved, particularly after the New York Journal published a copy of a letter from Spanish Foreign Minister Enrique Dupuy de Lôme criticizing the American President on February 9, 1898. Events moved swiftly after the explosion aboard the U.S.S. Maine on February 15. On March 9, Congress passed a law allocating fifty million dollars to build up military strength. On March 28, the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry finds that a mine blew up the Maine. On April 21 President McKinley orders a blockade of Cuba and four days later the U.S. declares war.

President William McKinley, inaugurated on March 4, 1897, was even more anxious to become involved, particularly after the New York Journal published a copy of a letter from Spanish Foreign Minister Enrique Dupuy de Lôme criticizing the American President on February 9, 1898. Events moved swiftly after the explosion aboard the U.S.S. Maine on February 15. On March 9, Congress passed a law allocating fifty million dollars to build up military strength. On March 28, the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry finds that a mine blew up the Maine. On April 21 President McKinley orders a blockade of Cuba and four days later the U.S. declares war. However, Dewey did not have enough manpower to capture Manila so Aguinaldo’s guerrillas maintained their operations until 15,000 U.S. troops arrived at the end of July. On the way, the cruiser Charleston stopped at Guam and accepted its surrender from its Spanish governor who was unaware his nation was at war. Although a peace protocol was signed by the two belligerents on August 12, Commodore Dewey and Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, leader of the army troops, assaulted Manila the very next day, unaware that peace had been declared.

However, Dewey did not have enough manpower to capture Manila so Aguinaldo’s guerrillas maintained their operations until 15,000 U.S. troops arrived at the end of July. On the way, the cruiser Charleston stopped at Guam and accepted its surrender from its Spanish governor who was unaware his nation was at war. Although a peace protocol was signed by the two belligerents on August 12, Commodore Dewey and Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, leader of the army troops, assaulted Manila the very next day, unaware that peace had been declared. They arrived in Cuba in late May.

They arrived in Cuba in late May. While U.S. commanders were deciding on a further course of action, Admiral Cervera left port only to be defeated by Schley. On July 16, the Spaniards agreed to the unconditional surrender of the 23,500 troops around the city. A few days later, Major General Nelson Miles sailed from Guantánamo to Puerto Rico. His forces landed near Ponce and marched to San Juan with virtually no opposition.

While U.S. commanders were deciding on a further course of action, Admiral Cervera left port only to be defeated by Schley. On July 16, the Spaniards agreed to the unconditional surrender of the 23,500 troops around the city. A few days later, Major General Nelson Miles sailed from Guantánamo to Puerto Rico. His forces landed near Ponce and marched to San Juan with virtually no opposition.