Urbanization code puerto rico: 292 Urbanization | Postal Explorer

Address Tips | FULLDISTRIBUTORS

Write it down correctly

If you are unsure of a full postal address, it is far better to ask the recipient or someone else who knows the address, than risk the delays that could result if you enter incorrect information.

Sending to Puerto Rico?

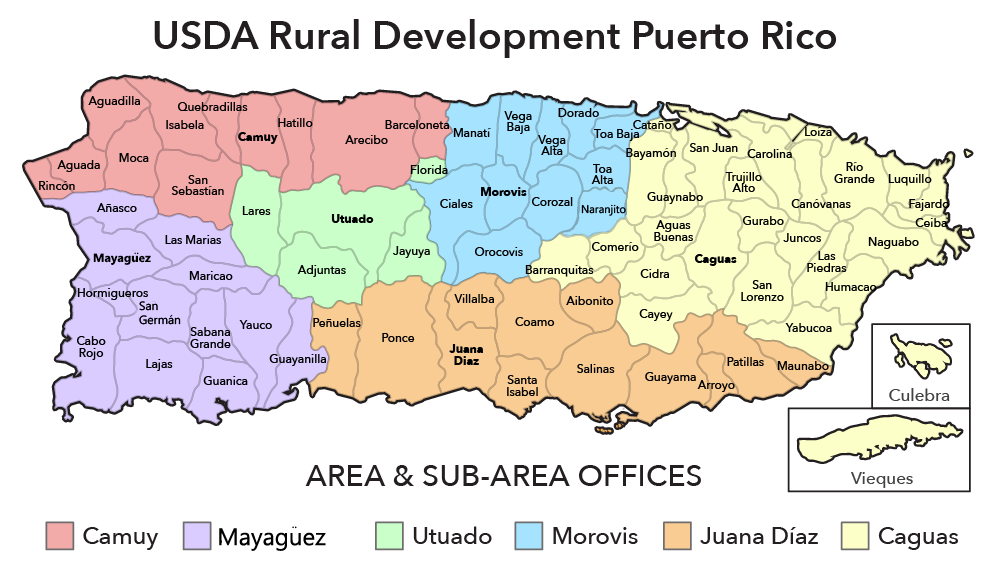

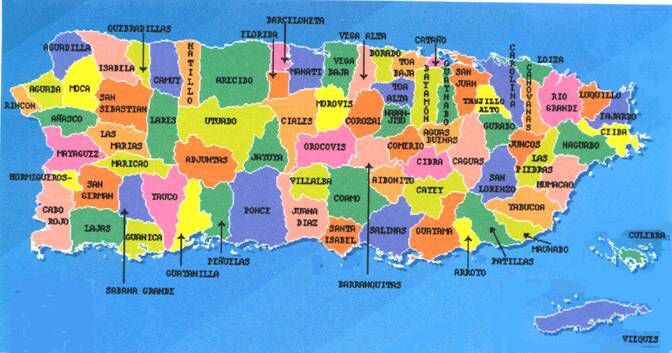

Puerto Rican addresses often include an urbanization code and often have Spanish address information. Check the most common formats down below.

USPS Zipcode Verification Tool

The United States Postal Service has an address verification tool you can use to make sure that the address you have is a viable address.

Find out more

common formats

Four-line Address

Four-line Address

Four-line Address

MRS MARIA SUAREZ

URB LAS GLADIOLAS

150 CALLE A

SAN JUAN PR 00926-3232

What to include:

Four-line Address

Four-line Address

Name

Urbanization

Street Number & Name

City, State & ZIP+4

Address without a Street Name

Address without a Street Name

Address without a Street Name

MR PEDRO RIOS

1234 URB LOS OLMOS

PONCE PR 00731-1235

What to include:

Address without a Street Name

Address without a Street Name

Name

Street Number & Urbanization

City, State & ZIP+4

Apartments or Office Buildings

Apartments or Office Buildings

Apartments or Office Buildings

MR EMILIO ARROYO

COND ASHFORD PALACE

1234 AVE ASHFORD APT 1A

SAN JUAN PR 00907-1234

What to include:

Apartments or Office Buildings

Apartments or Office Buildings

Name

Building Name

Street Number,Name & Apt

City, State & ZIP+4

complete address elements

A complete delivery address includes:

- Addressee name or other identifier and/or firm name where applicable.

- Urbanization name (Puerto Rico only, ZIP Code prefixes 006 to 009, if the area is so designated).

- Street number and name (including predirectional, suffix, and postdirectional as shown in USPS ZIP+4 Product for the delivery address or rural route.

- Secondary address unit designator and number (such as an apartment or suite number (APT 202, STE 100)).

- City and state (or authorized two-letter state abbreviation). Use only city names and city and state name abbreviations as shown in USPS City State Product.

- Correct 5-digit ZIP Code or ZIP+4 code. If a firm name is assigned a unique ZIP+4 code in the USPS ZIP+4 Product, the unique ZIP+4 code must be used in the delivery address.

Make sure all your letters and packages arrive at the right postal box.

What is Puerto Rico urbanization code? – BioSidmartin

Miscellaneous

Esther Fleming

What is Puerto Rico urbanization code?

An urbanization denotes an area, sector, or residential development within a geographic area. Commonly used in Puerto Rican urban areas, it is an important part of the addressing format, as it describes the location of a specific street. Generally, the abbreviation URB is placed before the urbanization name.

Commonly used in Puerto Rican urban areas, it is an important part of the addressing format, as it describes the location of a specific street. Generally, the abbreviation URB is placed before the urbanization name.

What is the address format for Puerto Rico?

In the Address Line 1 field write the house or building number and ‘Calle’. In the Address Line 2 field write the apartment, condominium, or building name. In the State field select “Puerto Rico”. In the Country field select “United States”.

What is the abbreviation for Puerto Rico?

PR

Appendix D – USPS State Abbreviations and FIPS Codes

| State | Postal Abbr. | FIPS Code |

|---|---|---|

| Puerto Rico | PR | 72 |

| Rhode Island | RI | 44 |

| South Carolina | SC | 45 |

| South Dakota | SD | 46 |

What is a HC 1 Box?

An HC Box is an address along a given star route that receives mail dropped off by an HC carrier.

What does USPS mean by urbanization?

Urbanization denotes an area, sector, or development within a geographic area. In addition to being a descriptive word, it precedes the name of the area. This URB descriptor, commonly used in urban areas of Puerto Rico, is an important part of the addressing format, as it describes the location of a given street.

Does Amazon deliver to PO box in Puerto Rico?

Expedited and Priority Shipping isn’t available for P.O. Boxes in Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Certain addresses aren’t eligible to receive shipments at all and an error message will appear at checkout. Available shipping options will appear at checkout when you enter a shipping address.

What happens if UPS delivers to a PO box?

UPS will only accept shipments to a valid street address. We do not deliver to P.O. Your package that is addressed to a P.O. Box may be delayed, will not be covered by any UPS Service Guarantee, and will require an address correction charge.

What does urbanization mean in Puerto Rico address?

Where is the city of Rio Grande Puerto Rico?

Río Grande ( Spanish pronunciation: [ˈri.o ˈɣɾande]) is a municipality of Puerto Rico located in the Northern Coastal Valley, north of Las Piedras, Naguabo and Ceiba; east of Loíza and Canóvanas and west of Luquillo. Río Grande is spread over eight barrios and Río Grande Pueblo (the downtown area and the administrative center of the city).

What does i51.4 urbanization mean in Puerto Rico?

I51.4 Urbanizations. An urbanization denotes an area, sector, or residential development within a geographic area. Commonly used in Puerto Rican urban areas, it is an important part of the addressing format, as it describes the location of a specific street.

Where can you find the same ZIP code in Puerto Rico?

In Puerto Rico, identical street names and address number ranges can be found within the same ZIP Code. In these cases, the urbanization name is the only element that correctly identifies the location of a particular address.

Category: Miscellaneous

Urbanization – World Bank Student Resource “Do You Know…?”

What is it?

Urbanization is the growth of cities due to the movement of people from rural areas in search of better jobs and better living conditions.

Cities and towns are at the center of a rapidly changing world economy – they are the cause and effect of global economic growth.

All over the world, cities are growing because people are moving out of rural areas in search of work, better living opportunities and a better future for their children.

For the first time in human history, most of the world’s population lives in cities.

- Three billion people – half of the world’s population – live in cities

- By 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities.

(In 1800, only 2% of people lived in cities. In 1950, only 30% of the world’s population was considered city dwellers.)

(In 1800, only 2% of people lived in cities. In 1950, only 30% of the world’s population was considered city dwellers.) - Nearly 180,000 people move to cities every day.

- 60 million people are added to the urban population every year in developing countries. This level of urban population growth will continue for the next 30 years.

- Many cities in Africa and Asia will double in size over the next 15 to 20 years.

Why does this concern me?

Urban population is growing faster than infrastructure is developing.

Many urban areas are growing at the expense of rural decline, forcing impoverished rural residents to move to cities in search of work.

New arrivals usually fail to find what was the purpose of resettlement, and they become the urban poor. When moving to the city, they often face the following problems:

- Lack of housing. Due to the lack of houses, settlers often build shelters on the outskirts of the city, usually on state-owned land.

These lands, as a rule, are unsuitable and dangerous for habitation. These are floodplains and river banks, steep slopes and lands after reclamation.

These lands, as a rule, are unsuitable and dangerous for habitation. These are floodplains and river banks, steep slopes and lands after reclamation. - Lack of necessary infrastructure. It is not uncommon for slum dwellers to live without electricity, running water, sewerage, roads and other utilities.

- No property rights . Slum dwellers, being illegal or unregistered city dwellers, have no property rights to the land they occupy, making it impossible to use the land as collateral for a loan.

Over the past 50 years, the number of slum dwellers has increased from 35 million to over 900 million. It could double over the next 30 years.

Slum dwellers make up the majority of the urban population in Africa and South Asia. According to some estimates, more than half of the world’s poor will live in cities by 2035.

Slum dwellers are at high risk of disease. In addition to suffering from pollution caused by burning unrefined fuels during cooking, using primitive stoves, and having limited access to water and sanitation, they have to face modern environmental hazards such as polluted city air, exhaust fumes, and industrial emissions. .

.

With the growth of cities, the number of environmental problems increases:

- Deterioration of air quality in cities. Every year, one million people die from urban air pollution.

- An increase in the number of vehicles , which leads to congestion of roads and an increase in the number of accidents. According to the World Health Organization, 500,000 people die and 15 million are injured in road traffic crashes every year in developing countries. Most of the victims are pedestrians and cyclists among the poor. People who manage to survive accidents often become disabled. For example, in Bangladesh, about 50% of hospital beds are reportedly occupied by road traffic victims.

Just the facts

The largest cities in the world

According to UN-Habitat, each of these 19 cities had more than 10 million inhabitants in 2000

No.| City | Population in millions | 1 | Tokyo | 26. |  4 4 2 | Mexico City | 18.1 | 3 | Bombay | 18.1 | 4 | Sao Paulo | 17.8 | 5 | New York | 16.6 | 6 | Lagos | 13.4 | 7 | Los Angeles | 13.1 | 8 | Kolkata | 12.9 | 9 | Shanghai | 12.9 | 10 | Buenos Aires | 12.6 | 11 | Dhaka | 12. |  3 3 12 | Karachi | 11.8 | 13 | Delhi | 11.7 | 14 | Jakarta | 11.0 | 15 | Osaka | 11.0 | 16 | Manila | 10.9 | 17 | Beijing | 10.8 | 18 | Rio de Janeiro | 10.6 | 19 | Cairo | 10.6 | |

In 1950, New York was the only city in the world with more than 10 million inhabitants.

What is the international community doing?

According to Jeffrey Sacks, director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, cities around the world should move in three strategic directions to ensure acceptable living conditions for all city residents:

- Urban planning that includes well-designed water and sewer systems, as well as public transportation and health systems.

- City Development Strategy, i.e. setting goals taking into account the conditions in a particular region.

- City management.

Local leaders and international development experts are trying to find answers to the following questions: “Where will these new city dwellers live? What land should they use? What schools will their children go to? Where will they get water? How will garbage be collected? Where should they vote? Who will protect them?”

International agencies also work with poor countries to achieve the following goals:

- Establish adequate infrastructure, including roads, housing, electricity, water and sanitation networks, schools and hospitals.

- Creation of legal settlements on the site of slums.

- Strengthening city government.

- Improving the lives of the poor and promoting equality.

What can I do?

Visit Idealist or UN Volunteers for information on opportunities to volunteer worldwide to promote sustainable development.

Visit the following sites:

- UN-Habitat is the United Nations agency that studies human settlements around the world.

- Cities Alliance is a worldwide association of cities and their development partners whose mission is to improve the lives of the urban poor.

Additional resources

- 2030 Sustainable Development Goals

1.2. Common law system

In England and Wales, the concept of common law property (pro perty law) until quite recently did not have an institution similar in tasks to continental condominium property, only in 2002 did the title commonhold appear. In a few Russian publications, the translation “common property”1 is usually used, which cannot be considered successful. As will be shown later, there is no common property (as continental law understands it) in this institution, which is just one of its distinguishing features. The literal translation “common ownership” is closer to understanding, because, as you know, all land in the Anglo-Saxon system of law belongs to the Crown, and, therefore, all other subjects of law have only titles (estates or interests), being entitled in a certain respect to the land, but without formally becoming owners2. To avoid ambiguity, we will use the English term in what follows.

To avoid ambiguity, we will use the English term in what follows.

The introduction of this design was preceded by a centuries-old history of property law. Unlike many other Anglo-Saxon legal orders, England did not move away from its classical legal institutions, even in times of rapid urbanization and the growth of high-rise buildings (primarily in the post-war period). Apartment buildings were in the long-term leasehold regime, in which the owners of the premises are not tenants, but for an artificially long period (for example, 99 or 150 years old) have a special title; often in English literature such owners are even classified as owners.

Why did the English legal order previously not allow “ownership” of the premises? The answer lies in the historical features of the English concept of property rights, going back to the time of the feudal system. The fact is that freehold estate, according to English law, is incompatible with positive obligations (positive covenants or obligations), since the holder of this broadest title cannot be bound by an obligation to perform actions. But without such obligations, it is impossible to imagine any property that has shared parts (whether it be corridors and elevators in a building or a common land plot under several

But without such obligations, it is impossible to imagine any property that has shared parts (whether it be corridors and elevators in a building or a common land plot under several

1 Strembelev S.V. Legal problems of managing apartment buildings: the role of HOAs. M., 2012. S. 7; Pacia T.M. Housing rights in England // Family and housing law. 2016. No. 3. P. 40.

2 Duddington J. Land Law. Harlow, 2011. P. 2–7.

11

A.E. Ageenko

detached houses). Leasehold does not have such historical restrictions, but there is a possibility of a conflict between the tenant and the landlord. In addition, leasehold1 has other disadvantages: limited term, decrease in the price of the title over time, the possibility of termination of the right due to breach of obligations.

The commonhold institution was intended to resolve the situation and replace leasehold by creating a scheme of “interdependent unit-holders” to manage the common parts of the object. As early as the 60s2 of the last century, its discussions began, the first of which was the Wilberforce Committee in 1965. In 1984, The Law Commission prepared the first report, which outlined a structure similar to the final commonhold institution. . Although, for example, the term3 itself was proposed back in 1978 by Sir B.R. Williams, Member of Parliament, as part of another leasehold reform. Already on this basis, The Law Commission issued three draft laws in 1990, 1996 and 2000, only the last one eventually became law4.

As early as the 60s2 of the last century, its discussions began, the first of which was the Wilberforce Committee in 1965. In 1984, The Law Commission prepared the first report, which outlined a structure similar to the final commonhold institution. . Although, for example, the term3 itself was proposed back in 1978 by Sir B.R. Williams, Member of Parliament, as part of another leasehold reform. Already on this basis, The Law Commission issued three draft laws in 1990, 1996 and 2000, only the last one eventually became law4.

1 Mackenzie J.-A., Phillips M. Textbook on Land Law. Oxford, 2010, pp. 267–268. As for negative obligations (restrictive covenants), they can be imposed on both titles without restrictions (see: Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002: Explanatory Notes. P. 4-5).

2 1960s coincidentally became the decade when many English-speaking countries introduced at the level of law the structure of floor ownership (English version – apartment ownership), for example, the USA, Singapore, Australia.

3 As they joked then: “A New Property Term – but not Property in a Term!” (See: Lu Xu. Commonhold Developments in Practice // Modern Studies in Property Law. Oxford; Portland, 2015. P. 333).

4 Looking ahead, we note that the reform in England failed. Commonhold has not gained popularity with developers, lawyers and property buyers. It was predicted that about 6,500 new objects in the commonhold regime would be registered every year, but in practice, by January 1, 2014, there were 16 of them. Commonhold is no longer discussed in the literature and in practice. One writer, for example, used the expression “neglected commonhold system” to describe the current state of affairs (see: Lu Xu. Op. cit. p. 332).

Reasons for the failure are commonly cited as follows: great difficulty in attracting people to the property market due to unavailability of mortgage financing; misunderstanding of the very ideology of commonhold, which results in unwillingness to bear the burden of ownership; lack of preferences in urban planning and rather high taxes; problems in the regulation of Company Law; passive government policy.

Thus, even today, the vast majority of subjects of law have at their disposal leasehold estate or leasehold tenure, if the legal relationship involves a long-term nature, and tenancy, if there is a lease of residential premises for a short period (see: Patsia T.M. Decree. cit., pp. 41–44). Actively used

12

Civil Law Regime of Floor (Housing) Property

The United States was built on an abundance of cheap land for the first 200 years of its development. The majority of the population had the opportunity to obtain a land plot in order to build a house and other necessary structures. Development at this first stage was horizontal, ie. the buildings were low-rise, and the first cities were rows of individual houses.

But by the end of the 19th century, land in urban areas began to rise in price actively, which stimulated multi-storey (primarily residential) construction. The US began to grow vertically. At first, multi-storey buildings still belonged to one person who could financially master such construction. Surplus space it rented

Surplus space it rented

vardu. But the welfare of tenants grew, and apartments became more and more desirable investment objects. For these fairly simple reasons, two new concepts appeared at once: condominium and cooperative2, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Australia also had a “great dream”: owning a house and a huge plot of land, for which, in fact, the first colonists went to this distant continent. The urbanism of that time ended with the thought of huge low-rise suburbs (by the way, 70–75% of the Australian population still live

detached houses). In the sense of justice of the local population, own home is synonymous with the title freehold. The colonists fled England, hating landlords, bailiffs and the very word “leasehold”. Therefore, it is natural that on the other side of the world they would not agree to any other title to the land, except for freehold 3.

security of tenure, which is simply necessary in the current paradigm of the real estate market in England and Wales.

1 Kabluchkov A.Yu. Institutions of cooperative and condominium in US housing law // Family and housing law. 2014. No. 3. P. 39-40. By the beginning of the XX century. used, among others, two more institutions: joint and shared ownership. The institution of a trust has not taken root in this legal area: it is aimed at meeting property needs and minimizes the role of the founder and beneficiary in making decisions on the use and disposal of property.

2 Only rental ownership, less protection, low levels of exclusivity make this form much less successful than condominiums in the US. In general, the cooperative appeared in the states on the east coast of the United States at the turn of 1960s and 1970s and was used for a strictly defined program (publicly assisted housing) (see: A.Yu. Kabluchkov, op. op. pp. 40–42). When introducing cooperatives, the United States took into account the experience of the Scandinavian countries, where this form is the main one.

3 See: Sherry C. Strata Title Property Rights: Private Governance of Multi-Owned Pro perties. New York, 2017. P. 11–14.

Strata Title Property Rights: Private Governance of Multi-Owned Pro perties. New York, 2017. P. 11–14.

13

A.E. Ageenko

But, as we have already found out, freehold has difficulties in applying positive obligations1. Australian lawyers got out of this predicament, considering that it is possible to create an effective system even through negative obligations alone (do not crush the object less than the minimum size; do not create non-residential premises, terraces, duplexes; do not build more than two floors, etc.). For developers, this meant the possibility of creating a quality product for the market (marketability). Until the 1960s, this regulation was sufficient due to the fact that society did not recognize apartments, considering such areas to be slums2. But for the same reasons as in other countries, Australia had to introduce a new institution3.

After about 10 years of legislative process, in which prominent lawyers and real estate developers played a decisive role, in 1961 an act was passed that allowed the creation of freehold title to apartments and other objects. Since the adoption of such acts falls within the competence of the states, the first (Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act)4 was adopted in the state of New South Wales5.

Since the adoption of such acts falls within the competence of the states, the first (Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act)4 was adopted in the state of New South Wales5.

1.3. Russian law

As for the question of when the floor property appeared in Russia, it still remains unanswered. In pre-revolutionary Russia, real estate issues were regulated by part I, volume X of the Code of Civil Laws. If the divisibility of courtyards (land) and buildings vertically in the text of the law does not meet with objections, then the dispute about the possibility of horizontal division of the house remains open. However,

1 In addition to the problems that arise with the future maintenance of a property, one must also understand the following feature of Anglo-Saxon law: land titles are the basis of a (private) urban planning system. The landlord, through leasehold, could impose as much positive and negative obligations as he needed to regulate building on his land. The title freehold establishes the freedom to use the object (see: Sherry C. Op. cit.).

Op. cit.).

2 The first apartment buildings appeared in 1921–1923 Legally, they were formalized like cooperatives in the United States (they were given a different name – a company title).

3 Back in the 50s of the XX century. committee for the preparation of the reform. Most of the committee members were initially in favor of developing the idea of a cooperative, but a minority was able to convince the rest that the cooperatives lacked mortgage financing, as well as an exclusive and permanent freehold title.

4 Currently under Strata Schemes Development Act 2015.

5 Sherry C. Op. cit. P. 15. Then Tasmania took over in 1962, Queensland in 1965, Western Australia and Victoria in 1967, the Australian Capital Territory in 1970, and so on. Basically they just copied the New South Wales text.

14

Civil law regime of floor (residential) property

most likely, separate premises could have been a separate object even then: L.A. Casso leaned towards this option and even cited some of the practice of the Senate. In our opinion, the fact that the law is silent about floor property, as well as many authoritative authors, suggests that at that time there were no socio-economic prerequisites for the formation of such an institution: the country was predominantly rural, and in the cities of that time, either low-rise buildings were used, which certain segments of the population could afford, or a lease agreement was applied.

In our opinion, the fact that the law is silent about floor property, as well as many authoritative authors, suggests that at that time there were no socio-economic prerequisites for the formation of such an institution: the country was predominantly rural, and in the cities of that time, either low-rise buildings were used, which certain segments of the population could afford, or a lease agreement was applied.

In Soviet literature, this institute had few mentions. Housing law was considered exclusively in the paradigm of public-industry regulation, and the main issues around which the discussion was built were issues of social hiring and housing funds. These topics were raised in the literature of that time, for example, in the works of S.I. Asknazia, V.P. Gribanov and other authors2.

With the transition to a market economy, the formation of a stratum of owners and the return to the classical property-law constructions in the field of real estate, the institution of condominium ownership has regained interest from the legislator, courts and researchers. This process took place against the background of unnatural circumstances: the privatization of the housing stock, carried out primarily due to fiscal interests3 and much earlier than the launch of land (the main real estate in the world), led to the current state of the market, when most transactions are made precisely on about the premises.

This process took place against the background of unnatural circumstances: the privatization of the housing stock, carried out primarily due to fiscal interests3 and much earlier than the launch of land (the main real estate in the world), led to the current state of the market, when most transactions are made precisely on about the premises.

1 Kasso L.A. Russian land law. M., 1906. S. 12–13. In addition, in the district of the Warsaw Court of Justice, the provisions of Art. 553 and 664 of the Civil Code of France, which means that in these areas the floor property definitely existed (see also: Duvernoy N.L. Readings on civil law. St. Petersburg, 1902. P. 130). There is no direct mention of floor ownership, but often in the text there are examples of establishing ownership of premises. Close to this position was V.B. Elyashevich. On the contrary, K.P. Pobedonostsev and K.N. Annenkov were supporters of the indivisibility of buildings in general, i.e. they also opposed vertical division (for more details, see: Chubarov V. V. Problems of legal regulation of real estate. M., 2006. P. 111–112).

V. Problems of legal regulation of real estate. M., 2006. P. 111–112).

2 See, for example: Asknaziy S.I. Soviet housing law: Textbook. M., 1940; Ginzburg S.N. Basic issues of housing law. M., 1940; Amfiteatrov G.N. Rights to residential buildings and use of residential premises. M., 1948; Asknaziy S.I., Braude I.L., Pergament A.I. Housing law. M., 1956; Gribanov V.P. Fundamentals of Soviet housing legislation. Moscow, 1983.

3 Sukhanov E.A. Decree. op. P. 361.

15

A.E. Ageenko

2. General characteristics of modern legal regulation

2.1. Legislative regulation of condominium property and the terms used to designate it

The concept of condominium property in various forms is known to almost all legal orders of the world. The first special laws were issued in Belgium (1924), Romania (1927), Brazil (1928), Greece (1929), Poland (1934), Italy (1934), Bulgaria (1935), Chile (1937), France (1938) , Uruguay (1946), Austria (1948), Argentina (1948), Bolivia (1949) and others. The first is the introduction of additions and changes to the existing codified acts that deviate from the classical and original provisions of the codes. This is what happened in Italy and Switzerland.

The first is the introduction of additions and changes to the existing codified acts that deviate from the classical and original provisions of the codes. This is what happened in Italy and Switzerland.

The second is the adoption of a special law, which, in its scope of application, repeals or develops the provisions of the code, or creates regulation from scratch. For example, this is done in Austria, England, Germany, Spain and China3.

Conditionally, as the third approach, we can designate regulation in the USA and Australia, where, respectively, either a federal act is adopted, and at the state level there is their own legislation4, or there is no nationwide act at all.

1 Pick E., Bärmann J. Wohnungseigentumsgesetz: Commentar. Munich, 2008. S. 25.

2 The Italian Civil Code of 1942 contains, like the Swiss Civil Code, an entire chapter (arts. 1117–1139) on condominiums in buildings. In both acts, the relevant chapters are in the section on joint ownership.

3 Respectively, these are the German WEG 1951 and the Austrian WEG 2002. In Spain Art. 396 of the Civil Code of 1889 establishes the basis for “horizontal” ownership. For more detailed regulation, in Article 396 of the Spanish Civil Code itself there is an indication of the adoption of a special act, at the moment the Law on Horizontal Property 49 is in force/1960, which does not apply to Catalonia. In England and Wales, the commonhold institution was introduced by the Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act (CLRA) in 2002, which came into force in 2004. In China, the condominium is governed by the Property Law Act 2007 (s. 70-83) and explanations of the highest court (Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China).

4 The United States has a Uniform Condominium Act, adopted in 1977, based on the experience of Puerto Rico Act 1958. But this Law is a model (recommendatory), it was ratified by only 14 states. The main regulation is contained in the legislation of the states (see: Ed irimane A. Op. cit. P. 1-5).

Op. cit. P. 1-5).

16

Civil law regime of floor (residential) property

Domestic legislation can be attributed to the second group. Despite Art. 130 and ch. 18 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, the main body of regulation is taken out in a special law1 – the Housing Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter – the RF HC). The specifics of Russian law is the hypertrophied public regulation of legal relations that develop with respect to real estate objects in the mode of floor ownership. Looking ahead, let us cite as an example Art. 293 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation: when the owner of the residential premises is used for other purposes, with a systematic violation of the rights and interests of neighbors, or in case of ownerless handling of housing with the assumption of destruction, a local government body, which has nothing to do with this object, files a lawsuit in court. Such regulation was permissible in Soviet times, when there was a single housing stock. But in the modern situation, the right to this claim should be granted to other owners in this object or to the society of owners as a whole (which is what foreign legal orders do). The same arguments are valid in relation to Art. 25–29LCD RF.

But in the modern situation, the right to this claim should be granted to other owners in this object or to the society of owners as a whole (which is what foreign legal orders do). The same arguments are valid in relation to Art. 25–29LCD RF.

Such regulation is inefficient: according to B.M. Gongalo, the Housing Code of the Russian Federation has long turned into a “Communal Code”2, which includes norms on the provision of residential premises under social rental agreements, on payment for residential premises and utilities, on the organization of major repairs and on the procedure for financing them, etc. . The RF LC contains a mixture of civil law norms and procedural norms of an administrative legal nature. By virtue of the public law basis, the RF LC is built on a different paradigm than all the above foreign acts. It is based on unknown content “housing rights”3, and Art. 16 LC RF, highlighting such objects as part of the

1 The LC RF is precisely an uncodified law, since it lacks a developed general part.

2 Suslova S.I. The right of common shared ownership of housing and housing legislation // Family and housing law. 2016. No. 5. P. 41. A separate question is about the essence of housing law as an industry, because its administrative and legal nature is obvious.

3 Krasheninnikov P.V. Housing law. M., 2016. P. 25. Even in the specialized literature, their content is revealed vaguely: “Taking into account the above approach, related to the complex nature of housing legal relations, it seems possible to divide housing rights into constitutional, civil and administrative ones.” Thus, a set of rights from various branches under the single name “housing law” is obtained.

17

A.E. Ageenko

the logo of the house, part of the apartment and the room, violates the concept of floor property, which considers an isolated and separate room as a minimal indivisible object.

Non-residential premises at the moment, in fact, do not have legislative regulation at all, there are only clarifications from the highest judicial instances about the need to apply the analogy of the law. This approach, which was previously encountered in law enforcement practice, was prescribed to the courts as mandatory, first by the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation1, and then by the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation2.

This approach, which was previously encountered in law enforcement practice, was prescribed to the courts as mandatory, first by the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation1, and then by the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation2.

As for the terms, there are many of them: in Germany and Austria – Wohnungseigentum, in Switzerland – Stockwerkeigentum, in England – commonhold, in the USA3 and Italy – condominium and condominio negli edifici, respectively, in Australia – strata title.

One of the distinguishing features of Russian law is the absence of an established term. The Civil Code of the Russian Federation and other normative legal acts contain only indications of the “ownership of residential premises”. In the literature, however, various kinds of translations by foreign institutions are usually used: “housing” or “floor”4 property, as well as “floor”5. In our opinion, it is the latter term that should enter the Russian legal literature and legislation as the main one. First, it arose historically first as a designation of horizontal property as opposed to the vertical property known since Roman times. The negative reminiscences of German authors about the Stockwerkeigentum should not offend a Russian lawyer. Secondly, the term “housing property” has a public-legal connotation, being associated with the Housing Code of the Russian Federation, and refers only to residential premises. As will be shown below, the scope of condominium ownership is much broader.

First, it arose historically first as a designation of horizontal property as opposed to the vertical property known since Roman times. The negative reminiscences of German authors about the Stockwerkeigentum should not offend a Russian lawyer. Secondly, the term “housing property” has a public-legal connotation, being associated with the Housing Code of the Russian Federation, and refers only to residential premises. As will be shown below, the scope of condominium ownership is much broader.

1 Paragraph 3 p. 1 of the Decree of the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation of July 23, 2009 No. 64 “On some issues of the practice of considering disputes about the rights of owners of premises to the common property of buildings” // Bulletin of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation. 2009. No. 9 (hereinafter referred to as Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation No. 64).

2 Clause 41 of the Decree of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of June 23, 2015 No. 25 “On the application by the courts of certain provisions of Section I of Part One of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation” // Bulletin of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2015. No. 8.

25 “On the application by the courts of certain provisions of Section I of Part One of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation” // Bulletin of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2015. No. 8.

3 Also used is cooperative, a form that was borrowed from Scandinavian legal orders.

4 Sukhanov E.A. Decree. op.

5 Egorov A.V. On the issue of delimiting premises into common and individual in the mode of “floor” property. M., 2015.

18

Civil law regime of floor (housing) property

2.2. Possible constructions of a storey property

Let’s move on from the analysis of how the storey property is regulated to the consideration of how it is structured.

In Germany, the 1951 WEG introduced two constructions at once: Wohnungsei gentum (“housing property”) and Teileigentum (“partial property”). The matter is complicated by the fact that among German lawyers there is no consensus on the structure of these constructions.

Residential property is (according to the letter of the law) a kind of systemic unity of two rights: Sondereigentum (“special property”) and Miteigentumsanteil (“share in shared ownership”). The first right applies to housing, namely to certain premises and building components belonging to these premises, which can be changed, created or abolished without damaging the property in common ownership or the rights of other owners, or without changing the architectural appearance of the building1. Thus, above what has fallen into special ownership, rises the sole proprietor (Alleigentümer)2. A share in common property is the main element of this composite legal structure, because it is to it that special property is “attached”, as the text of the law constantly reminds of. With respect to this right, the entitled person is considered to be a shareholder (Miteigentümer)3.

The first right applies to housing, namely to certain premises and building components belonging to these premises, which can be changed, created or abolished without damaging the property in common ownership or the rights of other owners, or without changing the architectural appearance of the building1. Thus, above what has fallen into special ownership, rises the sole proprietor (Alleigentümer)2. A share in common property is the main element of this composite legal structure, because it is to it that special property is “attached”, as the text of the law constantly reminds of. With respect to this right, the entitled person is considered to be a shareholder (Miteigentümer)3.

But in the literature, such an approach to the law is not accepted, for example, by Bärmann and Müller. Thus, both speak of a “three-part unity” (dreigliedrige Einheit) of housing property, highlighting membership in the society of owners (Mitgliedschaft in der Eigentümergemeinschaft) as the third element. The last of these says that every holder of “special property” must be granted membership,

The last of these says that every holder of “special property” must be granted membership,

1 § 5 Wohnungseigentumsgesetz.

2 Eichler H. Institutionen des Sachenrechts. bd. I. Berlin, 1957. S. 163.

3 Wilhelm J. Sachenrecht. Berlin, 2007. S. 764–765. The author gives an example of a specific case that was dealt with by the BayObLG (Higher Regional Court of Bavaria). Within the framework of residential property, shares in common property were created, to which the rights of “special property” were attached. Then, within the limits of one of these shares and the special property associated with it, the establishment of shared ownership of separate premises in one dwelling took place. The result was a kind of “legal matryoshka”, which in German literature is called Mit-Sondereigentum. In this case, the court was afraid of super-complex relations and did not recognize them (which is correct, because this clearly contradicts the imperative norm of § 3 II S. 1 WEG). But in practice, such relationships occur quite often. Ultimately, as Weitnauer says, such ambiguous relationships lead to the notoriety of the Stockwerkeigentum.

But in practice, such relationships occur quite often. Ultimately, as Weitnauer says, such ambiguous relationships lead to the notoriety of the Stockwerkeigentum.

4 See: Müller K. Sachenrecht. Berlin, 1997. S. 686; Bärmann J., Pick E. Kommentar zum Wohnungseigentumsgesetz. Munich, 1994, pp. 35–37. Fully borrowed exactly

19

A.E. Ageenko

because this is required for the effectiveness of its use. Through the conclusion of various agreements and decision-making, the value of the use of premises may change. Accordingly, membership in a management society of owners is a necessary component of a real legal position.

Another important aspect of the discussions in German literature is the question of which of these components is assigned the advantage. One position (Bärmann) is that neither has an advantage. Börner proceeds from the economic dominance of “special property”, it is in the foreground. Junker introduces the last possible variation1: priority over shares in common property. Based on the history of the emergence of the institution of housing property, its goals and objectives, as well as § 3 of the WEG, where “special property” is considered only as a restriction on shared ownership, we can conclude (and in general the prevailing opinion in Germany does2) that the priority remains for a share in the common property. “Special ownership” is admissible only in connection with this share, it forms only an “appendage” (Anhängsel)3 of shared ownership. According to German authors, economic relations only confirm this, because the parts of the building located

Based on the history of the emergence of the institution of housing property, its goals and objectives, as well as § 3 of the WEG, where “special property” is considered only as a restriction on shared ownership, we can conclude (and in general the prevailing opinion in Germany does2) that the priority remains for a share in the common property. “Special ownership” is admissible only in connection with this share, it forms only an “appendage” (Anhängsel)3 of shared ownership. According to German authors, economic relations only confirm this, because the parts of the building located

in shared ownership have a higher value than premises

in special ownership.

Teileigentum does not differ in content and meaning from Wohnungsei gentum, paragraph 6 of § 1 of the WEG, and does speak of the extension of housing ownership to “partial ownership”. Paragraph 3 of § 1 of the WEG distinguishes them on the subject: in “partial ownership”, the right of special ownership is established for premises of buildings that do not serve residential purposes in conjunction with a share in common property4.

(In 1800, only 2% of people lived in cities. In 1950, only 30% of the world’s population was considered city dwellers.)

(In 1800, only 2% of people lived in cities. In 1950, only 30% of the world’s population was considered city dwellers.) These lands, as a rule, are unsuitable and dangerous for habitation. These are floodplains and river banks, steep slopes and lands after reclamation.

These lands, as a rule, are unsuitable and dangerous for habitation. These are floodplains and river banks, steep slopes and lands after reclamation.