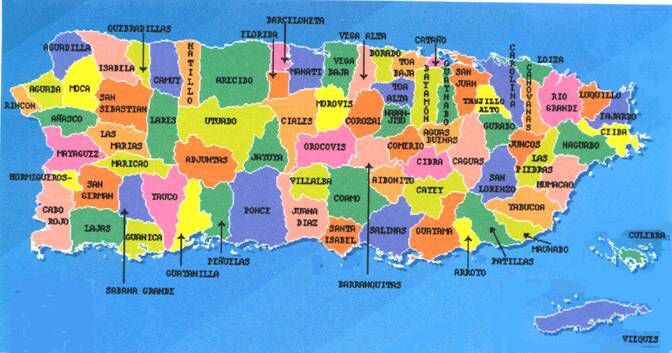

United states and puerto rico map: Where is Puerto Rico on the Map? Where is Puerto Rico Located

How the US has hidden its empire | US news

There aren’t many historical episodes more firmly lodged in the United States’s national memory than the attack on Pearl Harbor. It is one of only a few events that many people in the country can put a date to: 7 December 1941, the “date which will live in infamy,” as Franklin D Roosevelt put it. Hundreds of books have been written about it – the Library of Congress holds more than 350. And Hollywood has made movies, from the critically acclaimed From Here to Eternity, starring Burt Lancaster, to the critically derided Pearl Harbor, starring Ben Affleck.

But what those films don’t show is what happened next. Nine hours after Japan attacked the territory of Hawaii, another set of Japanese planes came into view over another US territory, the Philippines. As at Pearl Harbor, they dropped their bombs, hitting several air bases, to devastating effect.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was just that – an attack. Japan’s bombers struck, retreated and never returned. Not so in the Philippines. There, the initial air raids were followed by more raids, then by invasion and conquest. Sixteen million Filipinos – US nationals who saluted the stars and stripes and looked to FDR as their commander in chief – fell under a foreign power.

Not so in the Philippines. There, the initial air raids were followed by more raids, then by invasion and conquest. Sixteen million Filipinos – US nationals who saluted the stars and stripes and looked to FDR as their commander in chief – fell under a foreign power.

Contrary to popular memory, the event familiarly known as “Pearl Harbor” was in fact an all-out lightning strike on US and British holdings throughout the Pacific. On a single day, the Japanese attacked the US territories of Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island and Wake Island. They also attacked the British colonies of Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong, and they invaded Thailand.

At first, “Pearl Harbor” was not the way most people referred to the bombings. “Japs bomb Manila, Hawaii” was the headline in one New Mexico paper; “Japanese Planes Bomb Honolulu, Island of Guam” in another in South Carolina. Sumner Welles, FDR’s undersecretary of state, described the event as “an attack upon Hawaii and upon the Philippines”. Eleanor Roosevelt used a similar formulation in her radio address on the night of 7 December, when she spoke of Japan “bombing our citizens in Hawaii and the Philippines”.

Eleanor Roosevelt used a similar formulation in her radio address on the night of 7 December, when she spoke of Japan “bombing our citizens in Hawaii and the Philippines”.

That was how the first draft of FDR’s speech went, too: it presented the event as a “bombing in Hawaii and the Philippines”. Yet Roosevelt toyed with that draft all day, adding things in pencil, crossing other bits out. At some point he deleted the prominent references to the Philippines.

Why did Roosevelt demote the Philippines? We don’t know, but it’s not hard to guess. Roosevelt was trying to tell a clear story: Japan had attacked the US. But he faced a problem. Were Japan’s targets considered “the United States”? Legally, they were indisputably US territory. But would the public see them that way? What if Roosevelt’s audience didn’t care that Japan had attacked the Philippines or Guam? Polls taken slightly before the attack show that few in the continental US supported a military defense of those remote territories.

Roosevelt no doubt noted that the Philippines and Guam, although technically part of the US, seemed foreign to many. Hawaii, by contrast, was more plausibly “American”. Although it was a territory rather than a state, it was closer to North America and significantly whiter than the others.

Yet even when it came to Hawaii, Roosevelt felt a need to massage the point. So, on the morning of his speech, he made another edit. He changed it so that the Japanese squadrons had bombed not the “island of Oahu”, but the “American island of Oahu”. Damage there, Roosevelt continued, had been done to “American naval and military forces”, and “very many American lives” had been lost.

An American island, where American lives were lost – that was the point he was trying to make. If the Philippines was being rounded down to foreign, Hawaii was being rounded up to “American”.

One reporter in the Philippines described the scene in Manila as the crowds listened to Roosevelt’s speech on the radio. The president spoke of Hawaii and the many lives lost there. Yet he only mentioned the Philippines, the reporter noted, “very much in passing”. Roosevelt made the war “seem to be something close to Washington and far from Manila”.

The president spoke of Hawaii and the many lives lost there. Yet he only mentioned the Philippines, the reporter noted, “very much in passing”. Roosevelt made the war “seem to be something close to Washington and far from Manila”.

This was not how it looked from the Philippines, where air-raid sirens continued to wail. “To Manilans the war was here, now, happening to us,” the reporter wrote. “And we have no air-raid shelters.”

Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam – it wasn’t easy to know how to think about such places, or even what to call them. At the turn of the 20th century, when many were acquired (Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, Hawaii, Wake), their status was clear. They were, as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson unabashedly called them, colonies.

That spirit of forthright imperialism didn’t last. Within a decade or two, after passions had cooled, the c-word became taboo. “The word colony must not be used to express the relationship which exists between our government and its dependent peoples,” an official admonished in 1914. Better to stick with a gentler term, used for them all: territories.

Better to stick with a gentler term, used for them all: territories.

Yet a striking feature of the overseas territories was how rarely they were even discussed. The maps of the country that most people had in their heads didn’t include places such as the Philippines. Those mental maps imagined the US to be contiguous: a union of states bounded by the Atlantic, the Pacific, Mexico and Canada.

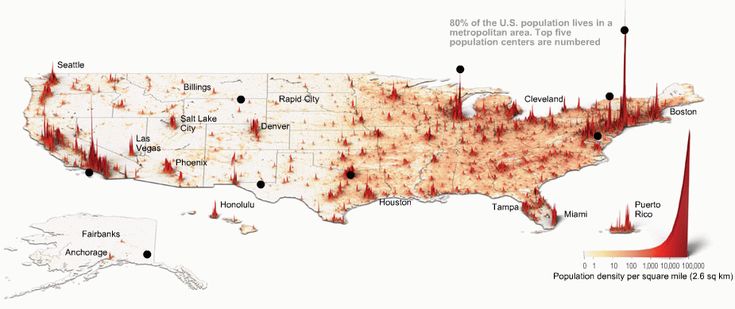

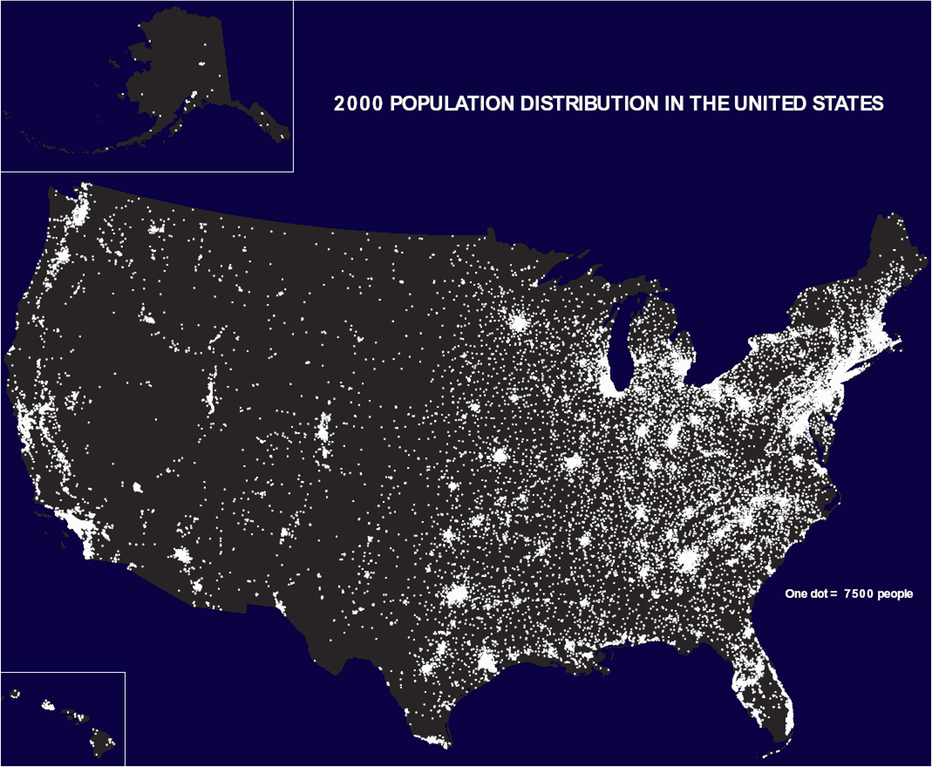

That is how most people envision the US today, possibly with the addition of Alaska and Hawaii. The political scientist Benedict Anderson called it the “logo map”, meaning that if the country had a logo, this shape would be it:

The US ‘logo map’

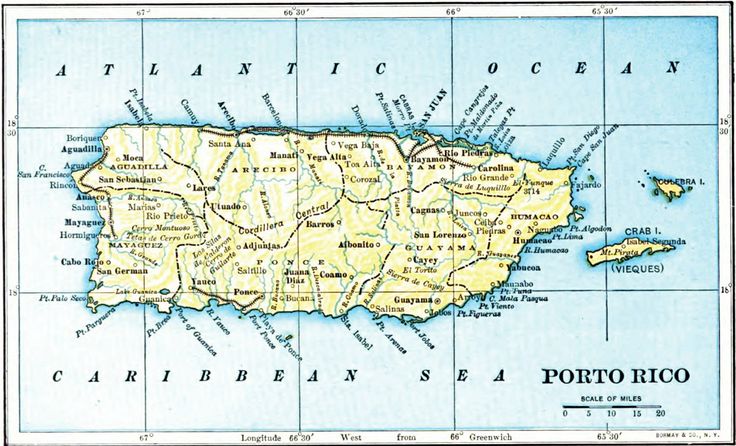

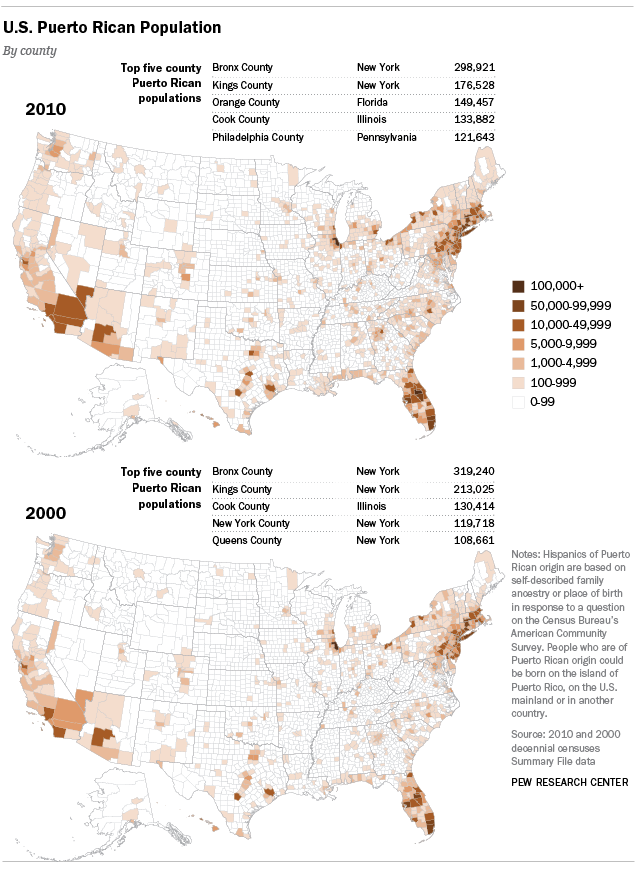

The problem with the logo map, however, is that it isn’t right. Its shape does not match the country’s legal borders. Most obviously, the logo map excludes Hawaii and Alaska, which became states in 1959 and now appear on virtually all published maps of the country. But it is also missing Puerto Rico, which, although not a state, has been part of the country since 1899. When have you ever seen a map of the US that had Puerto Rico on it? Or American Samoa, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, the Northern Marianas or any of the other smaller islands that the US has annexed over the years?

When have you ever seen a map of the US that had Puerto Rico on it? Or American Samoa, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, the Northern Marianas or any of the other smaller islands that the US has annexed over the years?

In 1941, the year Japan attacked, a more accurate picture would have been this:

A map of the ‘Greater United States’ as it was in 1941

What this map shows is the country’s full territorial extent: the “Greater United States”, as some at the turn of the 20th century called it. In this view, the place normally referred to as the US – the logo map – forms only a part of the country. A large and privileged part, to be sure, yet still only a part. Residents of the territories often call it the “mainland”.

On this to-scale map, Alaska isn’t shrunken down to fit into a small inset, as it is on most maps. It is the right size – ie, huge. The Philippines, too, looms large, and the Hawaiian island chain – the whole chain, not just the eight main islands shown on most maps – if superimposed on the mainland would stretch almost from Florida to California.

This map also shows territory at the other end of the size scale. In the century before 1940, the US claimed nearly 100 uninhabited islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Some claims were forgotten in time – Washington could be surprisingly lax about keeping tabs. The 22 islands included here are the ones that appeared in official tallies (the census or other governmental reports) in the 1940s. I have represented them as clusters of dots in the bottom left and right corners, although they are so small that they would be invisible if they were drawn to scale.

The logo map is not only misleading because it excludes large colonies and pinprick islands alike. It also suggests that the US is a politically uniform space: a union, voluntarily entered into, of states standing on equal footing with one another. But that is not true, and it has never been true. From its founding until the present day, the US has contained a union of American states, as its name suggests. But it has also contained another part: not a union, not states and (for most of its history) not wholly in the Americas – its territories.

What is more, a lot of people have lived in that other part. According to the census count for the inhabited territories in 1940, the year before Pearl Harbor, nearly 19 million people lived in the colonies, the great bulk of them in the Philippines. That meant slightly more than one in eight of the people in the US lived outside of the states. For perspective, consider that only about one in 12 was African American. If you lived in the US on the eve of the second world war, in other words, you were more likely to be colonised than black.

My point here is not to weigh forms of oppression against one another. In fact, the histories of African Americans and colonised peoples are tightly connected (and sometimes overlapping, as for the African-Caribbeans in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands). The racism that had pervaded the country since slavery also engulfed the territories. Like African Americans, colonial subjects were denied the vote, deprived of the rights of full citizens, called racial epithets, subjected to dangerous medical experiments and used as sacrificial pawns in war. They, too, had to make their way in a country where some lives mattered and others did not.

They, too, had to make their way in a country where some lives mattered and others did not.

What getting the Greater United States in view reveals is that race has been even more central to US history than is usually supposed. It hasn’t just been about black and white, but about Filipino, Hawaiian, Samoan and Chamoru (from Guam), too, among other identities. Race has not only shaped lives, but also the country itself – where the borders went, who has counted as “American”. Once you look beyond the logo map, you see a whole new set of struggles over what it means to inhabit the US.

Looking beyond the logo map, however, could be hard for mainlanders. The national maps they used rarely showed the territories. Even the world atlases were confusing. During the second world war, Rand McNally’s Ready Reference Atlas of the World – like many other atlases at the time – listed Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and the Philippines as “foreign”.

A class of seventh-grade girls at the Western Michigan College Training School in Kalamazoo scratched their heads over this. They had been trying to follow the war on their maps. How, they wondered, could the attack on Pearl Harbor have been an attack on the US if Hawaii was foreign? They wrote to Rand McNally to inquire.

They had been trying to follow the war on their maps. How, they wondered, could the attack on Pearl Harbor have been an attack on the US if Hawaii was foreign? They wrote to Rand McNally to inquire.

“Although Hawaii belongs to the United States, it is not an integral part of this country,” the publisher replied. “It is foreign to our continental shores, and therefore cannot logically be shown in the United States proper.”

The girls were not satisfied. Hawaii is not an integral part of this country? “We believe this statement is not true,” they wrote. It is “an alibi instead of an explanation”. Further, they continued, “we feel that the Rand McNally atlas is misleading and a good cause for the people of outlying possessions to be embarrassed and disturbed”. The girls forwarded the correspondence to the Department of the Interior and asked for adjudication. Of course, the seventh-graders were right. As an official clarified, Hawaii was, indeed, part of the US.

Yet the government could be just as misleading as Rand McNally on this score. Consider the census: according to the constitution, census takers were required to count only the states, but they had always counted the territories, too. Or, at least, they had counted the continental territories. The overseas territories were handled differently. Their populations were noted, but they were otherwise excluded from demographic calculations. Basic facts about how long people lived, how many children they had, what races they were – these were given for the mainland alone.

Consider the census: according to the constitution, census takers were required to count only the states, but they had always counted the territories, too. Or, at least, they had counted the continental territories. The overseas territories were handled differently. Their populations were noted, but they were otherwise excluded from demographic calculations. Basic facts about how long people lived, how many children they had, what races they were – these were given for the mainland alone.

The maps and census reports that mainlanders saw presented them with a selectively cropped portrait of their country. The result was profound confusion. “Most people in this country, including educated people, know little or nothing about our overseas possessions,” concluded a governmental report written during the second world war. “As a matter of fact, a lot of people do not know that we have overseas possessions. They are convinced that only ‘foreigners’, such as the British, have an ‘empire’. Americans are sometimes amazed to hear that we, too, have an ‘empire’.”

Americans are sometimes amazed to hear that we, too, have an ‘empire’.”

The proposition that the US is an empire is less controversial today. The case can be made in a number of ways. The dispossession of Native Americans and relegation of many to reservations was pretty transparently imperialist. Then, in the 1840s, the US fought a war with Mexico and seized a third of it. Fifty years later, it fought a war with Spain and claimed the bulk of Spain’s overseas territories.

Empire isn’t just landgrabs, though. What do you call the subordination of African Americans? Starting in the interwar period, the celebrated US intellectual WEB Du Bois argued that black people in the US looked more like colonised subjects than like citizens. Many other black thinkers, including Malcolm X and the leaders of the Black Panthers, have agreed.

Or what about the spread of US economic power abroad? The US might not have physically conquered western Europe after the second world war, but that didn’t stop the French from complaining of “coca-colonisation”. Critics there felt swamped by US commerce. Today, with the world’s business denominated in dollars, and McDonald’s in more than 100 countries, you can see they might have had a point.

Critics there felt swamped by US commerce. Today, with the world’s business denominated in dollars, and McDonald’s in more than 100 countries, you can see they might have had a point.

Flags on top of the fortress in Old San Juan in Puerto Rico. Photograph: Anton Gorbov/Alamy

Then there are the military interventions. The years since the second world war have brought the US military to country after country. The big wars are well-known: Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan. But there has also been a constant stream of smaller engagements. Since 1945, US armed forces have been deployed abroad for conflicts or potential conflicts 211 times in 67 countries. Call it peacekeeping if you want, or call it imperialism. But clearly this is not a country that has kept its hands to itself.

Yet among all the talk of empire, one thing that often slips from view is actual territory. Yes, many would agree that the US is or has been an empire, for all the reasons above. But how much can most people say about the colonies themselves? Not, I would wager, very much.

It is not as if the information isn’t out there. Scholars, many working from the sites of empire themselves, have assiduously researched this topic for decades. The problem is that their works have been sidelined – filed, so to speak, on the wrong shelves. They are there, but as long as we have the logo map in our heads, they will seem irrelevant. They will seem like books about foreign countries. The confusion and shoulder-shrugging indifference that mainlanders displayed at the time of Pearl Harbor hasn’t changed much at all.

I will confess to having made this conceptual filing error myself. Although I studied US foreign relations as a doctoral student and read countless books about “American empire” – the wars, the coups, the meddling in foreign affairs – nobody ever expected me to know even the most elementary facts about the territories. They just didn’t feel important.

It wasn’t until I travelled to Manila, researching something else entirely, that it clicked. To get to the archives, I would travel by “jeepney”, a transit system originally based on repurposed US army jeeps. I boarded in a section of Metro Manila where the streets are named after US colleges (Yale, Columbia, Stanford, Notre Dame), states and cities (Chicago, Detroit, New York, Brooklyn, Denver), and presidents (Jefferson, Van Buren, Roosevelt, Eisenhower). When I would arrive at my destination, the Ateneo de Manila University, one of the country’s most prestigious schools, I would hear students speaking what sounded to my Pennsylvanian ears to be virtually unaccented English. Empire might be hard to make out from the mainland, but from the sites of colonial rule themselves, it is impossible to miss.

To get to the archives, I would travel by “jeepney”, a transit system originally based on repurposed US army jeeps. I boarded in a section of Metro Manila where the streets are named after US colleges (Yale, Columbia, Stanford, Notre Dame), states and cities (Chicago, Detroit, New York, Brooklyn, Denver), and presidents (Jefferson, Van Buren, Roosevelt, Eisenhower). When I would arrive at my destination, the Ateneo de Manila University, one of the country’s most prestigious schools, I would hear students speaking what sounded to my Pennsylvanian ears to be virtually unaccented English. Empire might be hard to make out from the mainland, but from the sites of colonial rule themselves, it is impossible to miss.

The Philippines is not a US territory any more; it got its independence after the second world war. Other territories, although they were not granted independence, received new statuses. Puerto Rico became a “commonwealth”, which ostensibly replaced a coercive relationship with a consenting one. Hawaii and Alaska, after some delay, became states, overcoming decades of racist determination to keep them out of the union.

Hawaii and Alaska, after some delay, became states, overcoming decades of racist determination to keep them out of the union.

Yet today, the US continues to hold overseas territory. Besides Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands and a handful of minor outlying islands, the US maintains roughly 800 overseas military bases around the world.

None of this, however – not the large colonies, small islands, or military bases – has made much of a dent on the mainland mind. One of the truly distinctive features of the US’s empire is how persistently ignored it has been. This is, it is worth emphasising, unique. The British weren’t confused as to whether there was a British empire. They had a holiday, Empire Day, to celebrate it. France didn’t forget that Algeria was French. It is only the US that has suffered from chronic confusion about its own borders.

The reason is not hard to guess. The country perceives itself to be a republic, not an empire. It was born in an anti-imperialist revolt and has fought empires ever since, from Hitler’s Thousand-Year Reich and the Japanese empire to the “evil empire” of the Soviet Union. It even fights empires in its dreams. Star Wars, a saga that started with a rebellion against the Galactic Empire, is one of the highest-grossing film franchises of all time.

It was born in an anti-imperialist revolt and has fought empires ever since, from Hitler’s Thousand-Year Reich and the Japanese empire to the “evil empire” of the Soviet Union. It even fights empires in its dreams. Star Wars, a saga that started with a rebellion against the Galactic Empire, is one of the highest-grossing film franchises of all time.

This self-image of the US as a republic is consoling, but it is also costly. Most of the cost has been paid by those living in the colonies and around the military bases. The logo map has relegated them to the shadows, which are a dangerous place to live. At various times, the inhabitants of the US empire have been shot, shelled, starved, interned, dispossessed, tortured and experimented on. What they haven’t been, by and large, is seen.

The logo map carries a cost for mainlanders, too. It gives them a truncated view of their own history, one that excludes part of their country. It is an important part. The overseas parts of the US have triggered wars, brought forth inventions, raised up presidents and helped define what it means to be “American”. Only by including them in the picture do we see a full portrait of the country – not as it appears in its fantasies, but as it actually is.

Only by including them in the picture do we see a full portrait of the country – not as it appears in its fantasies, but as it actually is.

How to Hide an Empire: A Short History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr will be published by Bodley Head on 28 February. Buy it at guardianbookshop.com

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

National Storm Surge Risk Maps

Analyses & Forecasts

- Tropical Cyclone Products

- Tropical Weather Outlooks

- Marine Products

- Audio/Podcasts

- RSS Feeds

- GIS Products

- Alternate Formats

- Tropical Cyclone Product Descriptions

- Marine Product Descriptions

▾

Data & Tools

- Satellite Imagery

- Radar Imagery

- Aircraft Reconnaissance

- Tropical Analysis Tools

- Experimental Products

- Lat/Lon Distance Calculator

- Blank Tracking Maps

▾

Educational Resources

- Be Prepared!

NWS Hurricane

Prep Week - NWS Hurricane Safety

- Outreach Documents

- Storm Surge

- Watch/Warning Breakpoints

- Climatology

- Tropical Cyclone Names

- Wind Scale

- Records and Facts

- Historical Hurricane Summaries

- Forecast Models

- NHC Publications

- NHC Glossary

- Acronyms

- Frequent Questions

- Be Prepared!

▾

Archives

- Tropical Cyclone Advisories

- Tropical Weather Outlooks

- Tropical Cyclone Reports

- Tropical Cyclone Forecast Verification

- Atlantic Current Season Summary

- E.

Pacific Current Season Summary

Pacific Current Season Summary - C. Pacific Current Season Summary

- NHC News Archive

- Product & Service Announcements

- Other Archives: HURDAT,

Track Maps,

Marine Products,

and more

▾

About

- National Hurricane Center

- Central Pacific

Hurricane Center - Contact Us

▾

Search

Search For

NWS

All NOAA▾

Surge Overview | National Surge Hazard Maps | Storm Surge Unit | SLOSH | Surge Products | Local Impacts | FAQ | Resources

Contents

- Introduction to the Risk Maps

- Interactive Map Viewer

- Technical Description

- Population at Risk from Storm Surge Inundation

- Data Availability and Download

- Data Citation and Disclaimer

Introduction to the Risk Maps

This national depiction of storm surge flooding vulnerability helps people living in

hurricane-prone coastal areas. These maps make it clear that storm surge is not just a

These maps make it clear that storm surge is not just a

beachfront problem, with the risk of storm surge extending many miles inland from the

immediate coastline in some areas. Storm Surge Risk Maps are provided for the U.S. Gulf and East Coasts, Hawaii, Southern California, U.S. territories – Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and American Samoa. Additional international areas that are mapped include Hispaniola and parts of the Yucatan Peninsula. If you discover via these maps that you live in an area

vulnerable to storm surge, find out today if you live in a hurricane storm surge evacuation

zone as prescribed by your local emergency management agency. If you do live in such

an evacuation zone, decide today where you will go and how you will get there, if and when

you’re instructed by your emergency manager to evacuate. If you don’t live in one of those

evacuation zones, then perhaps you can identify someone you care about who does live in an

evacuation zone, and you could plan in advance to be their inland evacuation destination –

if you live in a structure that is safe from the wind and outside of flood-prone areas.

What’s New with Version 3

- Reprocessed U.S. Gulf and East Coast with latest SLOSH grids in 2021 and at an improved grid cell size

- Addition of Southern California, Guam, American Samoa, and Yucatan Peninsula Maps

Interactive Map Viewer

Storm Surge Risk Maps |

Technical Description

Introduction

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), specifically the National

Weather Service’s (NWS) National Hurricane Center (NHC), utilizes the hydrodynamic Sea,

Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes (SLOSH) model to

simulate storm surge from tropical cyclones.

Storm surge information is provided to federal, state, and local partners

to assist in a range of planning processes, risk assessment studies, and operational

decision-making. In regards to the former, tens of thousands of climatology-based

hypothetical tropical cyclones are simulated in each SLOSH basin (or grid), and the

potential storm surges are calculated. Storm surge composites – Maximum Envelopes of Water

Storm surge composites – Maximum Envelopes of Water

(MEOWs) and Maximum of MEOWs (MOMs) – are created to assess and visualize storm surge

risk under varying conditions. While MEOWs and MOMs provide a local assessment of storm surge

risk, they do not provide a seamless perspective of the hazard owing to the many discrete

SLOSH grids. This section briefly describes the scientific techniques used to create the

seamless inundation maps for Category 1-5 hurricanes using the SLOSH MOM product as well

as a description of the datasets and map viewer available to the public.

SLOSH Storm Surge Modeling

SLOSH has been used operationally for more than three decades. Over this time,

SLOSH has provided valuable and accurate storm surge forecasts. For planning purposes,

the NHC uses a representative sample of hypothetical storms to estimate the near

worst–case scenario of flooding for each hurricane category. These SLOSH simulations

are used to create a set of operational and planning products.

The NHC provides two products based on hypothetical hurricanes: MEOWs and MOMs.

MEOWs are created by computing the maximum storm surge resulting from up to

100,000 hypothetical storms simulated through each SLOSH grid of varying forward

speed, radius of maximum wind, intensity (Categories 1-5), landfall location,

tide level, and storm direction. A MEOW product is created for each combination

of category, forward speed, storm direction, and tide level. SLOSH products exclude

Category 5 storms north of the NC/VA border and for Hawaii. For each storm combination, parallel storms

make landfall in 5 to 10 mile increments along the coast within the SLOSH grid, and the

maximum storm surge footprint from each simulation is composited, retaining the

maximum height of storm surge in a given basin grid cell. These are called MEOWs and no

single hurricane will produce the regional flooding depicted in the MEOWs. SLOSH model

MOMs are an ensemble product of maximum storm surge heights. SLOSH MOMs are created for each storm

SLOSH MOMs are created for each storm

category by retaining the maximum storm surge value in each grid cell for all the MEOWs, regardless

of the forward speed, storm trajectory, or landfall location. SLOSH MOMs are available for

mean tide and high tide scenarios and represent the near worst-case scenario of flooding under ideal

storm conditions. A high tide initial water level was used for the storm surge risk maps.

SLOSH employs curvilinear polar, elliptical, and hyperbolic telescoping mesh grids to

simulate the storm surge hazard. The spatial coverage for each SLOSH grid ranges from an

area the size of a few counties to a few states. The resolution of individual grid cells

within each basin ranges from tens to hundreds of meters to a kilometer or more. Sub–grid

scale water features and topographic obstructions such as channels, rivers, and cuts and

levees, barriers, and roads, respectively are parameterized to improve the modeled water

levels. Figure 1 shows the SLOSH basins used to create the surge risk maps.

Figure 1. The SLOSH basins used to create the storm surge risk maps. SLOSH grids are not drawn to scale.

Storm Surge and Wave Modeling in Puerto Rico, USVI, Hawaii, and Southern California

In locations that have a steep and narrow continental shelf, wave setup can be a substantial

contributor to the total water level rise observed during a tropical cyclone. Wave setup is

defined as the increase in mean water level due to momentum transfer to the water column by

waves that are breaking or otherwise dissipating their energy. Through NOAA’s Integrated Ocean

Observing System (IOOS) Coastal and Ocean Modeling Testbed (COMT) the SLOSH model has been

loosely coupled to the Simulating Waves Nearshore (SWAN) third-generation wave model,

developed at Delft University of Technology

(http://www.swan.tudelft.nl/),

for storm surge modeling applications in island regions such as Puerto Rico, USVI, and Hawaii. In these

locations, SLOSH+SWAN simulations were conducted to create MEOW and MOM products that account

for the increase in the mean water level due to wave setup.

Storm Surge Wave Modeling for Guam and American Samoa

For Guam and American Samoa, the SLOSH model has been coupleed with an efficient parametric wind wave model courtesy of NOAA/NCEP/EMC. SLOSH+Wave simulations were conducted to create MEOW and MOM products that account for the increase in the mean water level due to wave setup. Data has been processed by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) Storm Surge Unit.

Storm Surge and Wave Modeling in Hispaniola Guam and Yucatan Peninsula

Through the USAID/WMO Coastal Inundation and Flooding Demonstration Project for the Island of Hispaniola, |

Digital Elevation Model

An accurate digital elevation model (DEM) takes considerable time, resources, and expertise to

develop and is required to compute inundation. Two datasets were used to create the DEM:

- The NOAA Office for Coastal Management (OCM) high-resolution seamless raster elevation

dataset (https://coast.noaa.gov/slr/) - U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 3D Elevation Program (3DEP) dataset

(https://www.usgs.gov/3d-elevation-program).

To create this map for the US Gulf and East Coasts, the 3DEP and OCM DEMs were resampled to 1/3 arc-second (about 10 m) using a

bilinear interpolation and mosaicked together to produce a seamless raster elevation dataset.

The NOAA OCM high-resolution DEMs were used for Puerto Rico, USVI, Hawaii, Guam, and Amercian Samoa. The

native grid cell size for that data is about 3m and for the purposes of this analysis, that data was resampled to a

grid cell size of about 9 meters.

In International areas outside of the U.S., such as Hispaniola and the Yucatan Peninsula, the analysis uses TanDEM-X (TDX) DEM data provided by German Aerospace Center (DLR). Resolution of TDX DEM is 0.4 arc seconds

in latitudinal direction and varies in longitudinal direction between 0.4 arc seconds (equator) and 4 arc seconds (85 degrees N/S) (Wessel, 2016).

In partnership with the Department of Earth and Environment/International Hurricane Research Center at the Florida International University,

the raw data was filtered to remove non-ground features.

Seamless Mapping Methodology

The process to create storm surge inundation maps from the existing SLOSH MOM products requires

several technical steps. First, the usable areas of the SLOSH grids were reduced to ignore spurious

data along the grid boundaries. The SLOSH basins have considerable overlap to allow for complete

storm surge coverage for planning and operations. Merging these basins into a seamless product

requires specialized technical considerations. Since the grid boundaries yield unreliable data,

Since the grid boundaries yield unreliable data,

basin overlap was minimized, and the high-resolution and center portions of grids were retained.

The process used herein leveraged both SLOSH basin building and surge modeling expertise at NHC.

Second, the maximum water levels in each MOM were merged onto a uniform grid for processing. The

data were merged onto the NWS National Digital Forecast Database (NDFD) Lambert Conformal projected

grid with a horizontal resolution of roughly 625 m (the actual resolution varies by latitude). Lastly,

the merged MOM grids were processed through Esri ArcGIS to subtract the land elevation and create a

seamless raster of inundation. It should be noted that the SLOSH MOM storm surge risk data used to

create these maps are constrained by the extent of the SLOSH grids. High-quality maps are essential

for effective risk communication.

Concluding Remarks

This page outlines the approach to merging the SLOSH MOM products to create a seamless view of

storm surge inundation and risk for Category 1-5 hurricanes. Using social science research, the

Using social science research, the

carefully derived and high resolution inundation maps provide a means for effective risk communication and

analysis. The maps show that all coastal regions mapped are vulnerable to storm surge inundation, and the risk significantly increases with increasing hurricane category. Locations along the Gulf of Mexico are extremely vulnerable to storm surge, in terms of

both height and inland extent due to a wide and flat continental shelf over the majority of the region and

low-lying land elevations extending well inland. Puerto Rico, USVI, Hawaii, Southern California, American Samoa, Guam, Hispaniola, and the Yucatan Peninsula are also

vulnerable to storm surge and wave impacts. Large bays, tidal rivers, etc. are extremely vulnerable to

storm surge flooding. These data and this approach taken to inform the public of storm surge risk are valuable

to federal, state, and local NOAA partners, academic, private, and other various organizations.

Data Availability and Download

Download Data

Storm surge risk maps are available for Texas to Maine, Puerto Rico, USVI, Hawaii, Southern California, Guam, American Samoa, Hispaniola, and the Yucatan Peninsula. The data are

The data are

available in GeoTIFF (https://www.ogc.org/standards/geotiff/)

format for use in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software. Comprehensive metadata are provided with

each GIS file describing the data and its limitations. Storm surge inundation datasets are created using

the high tide scenario SLOSH MOM products for all regions. Each dataset contains an ESRI

World File (.tfw) and metadata .xml file. These GeoTIFFs are 8-bit unsigned integer raster datasets that

correspond to 1 ft inundation bins (e.g., Class Value 1 corresponds to the 0-1 ft inundation bin, Class Value 2

corresponds to the 1-2 ft inundation bin, and so on). The maximum Class Value is 21, and inundation

in excess of 20 ft is assigned a Class Value of 21. A Class Value of 99 is assigned to leveed areas.

A more detailed description of the data can be found in the associated metadata.

- Download – Texas to Maine (high tide scenario)(Updated Version 3- 6/2022)

- Download – Puerto Rico (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)

- Download – U.

S. Virgin Islands (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)

S. Virgin Islands (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018) - Download – Hawaii (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)

- Download – Southern California (high tide scenario) (Added Version 3 – 6/2022))

- Download – Guam (high tide scenario) (Added Version 3 – 6/2022))

- Download – American Samoa (high tide scenario) (Added Version 3 – 6/2022))

- Download – Hispaniola (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)

- Download – Yucatan Peninsula (high tide scenario) (Added Version 3 – 6/2022))

Link to Risk Maps on NOAA Geoplatform

Update Schedule

The storm surge risk maps and GIS data (if a new version is available)

will be updated as new SLOSH grids and DEM data are processed.

Data Citation and Disclaimer

Preferred Data Citation

The first version of the SLOSH storm surge hazard maps, released in November 2014,

was published in the American Meteorological Society (AMS) Journal of Weather, Climate and

Society, titled “A National View of Storm Surge Risk and Inundation”.

The publication is available online at

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/WCAS-D-14-00049.1

and the preferred citation for the data and map service is as follows:

Zachry, B. C., W. J. Booth, J. R. Rhome, and T. M. Sharon, 2015: A National View of Storm Surge Risk and Inundation.

Weather, Climate, and Society, 7(2), 109–117. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/WCAS–D–14–00049.1

Disclaimer

The data and maps in this tool illustrate the height of possible storm surge flooding under

certain scenarios, and do not account for erosion, subsidence, sea-level change or future construction. Water

levels are based on storm surge scenarios in the referenced SLOSH MOM tide scenario. The data, maps, and information

provided should only be used as a tool for general education/awareness of the storm surge

hazard at a city/community level (not for a parcel level/grid cell assessment). The SLOSH MOM storm surge risk data

used to create these maps are constrained by the extent of the SLOSH grids and users should be aware that risk due

to storm surge flooding could extend beyond the areas depicted in these maps. This map

This map

should not be used to replace the maps used for hurricane evacuation zones. Hurricane

evacuation zones are drawn at a local and state level and consider additional information

and specific criteria for a particular region in addition to the storm surge hazard.

Users are urged to consult local officials for flood risk inside the hatched areas marked as

leveed areas in the map. The data and maps in this tool are provided

“as is”, without warranty to their performance, merchantable state, or fitness for any particular

purpose. The entire risk associated with the results and performance of these data is assumed by

the user. This tool should be used strictly as a planning reference and storm surge risk awareness

tool and not for navigation, permitting, legal, or regulatory purposes. Any conclusions drawn from the

analysis of this information are not the responsibility of the National Weather Service, National Hurricane

Center, Office for Coastal Management, or its partners.

puerto rico free vector | Download it now!

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse, you agree to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies. Find out more here.

home

Vector

org/ListItem”>

Complain

Download

(12.6 KB)

puerto rico clip art

Puerto Rico Flag clip art

Flag of Russia vector 2

kurdistan flag

Pictures of the official flag of Israel

Flag of Russia vector

Flag Of North Atlantic Treaty Organization clip art

Flag of Santander clip art

Sakai Osaka Flag clip art

Another US aggression, or How Cuba and the Philippines were captured

possessions in the West Indies (islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico) and the Philippines. In simple terms, the American government simply could not survive what Spain had by the end of 19century, several “pearls” remained – Cuba, the Philippine Islands, Guam and Puerto Rico, these islands possessed a variety of resources, and were also located on important sea lanes.

In simple terms, the American government simply could not survive what Spain had by the end of 19century, several “pearls” remained – Cuba, the Philippine Islands, Guam and Puerto Rico, these islands possessed a variety of resources, and were also located on important sea lanes.

Not invaders. Liberators…

What path has the United States already taken by this time?

The young country “successfully” solved a number of its internal problems. Finally crushed the resistance of Native Americans – Indian tribes; in the 1860s and 1890s, the lands that still belonged to the Indians in the west of North America were seized and became the property of farmers and various companies. And the Indians were destroyed, partially deported and driven into reservations. Decided the issue and division of the country into South and North. Large-scale capitalist production developed rapidly, protected by high protectionist tariffs.

Now American capital needed a variety of cheap natural raw materials, markets for its products, sea routes covered by naval bases. The political superstructure of the United States has always fulfilled the order of the financial and industrial oligarchy – back in the first half of the 19th century, the “Monroe Doctrine” was proclaimed. According to it, North and South America were proclaimed a zone closed to European colonization. It was assumed that it would be dominated by the States. At the end of the 19th century, the American government pursued a policy of expanding economic influence in Latin America and Asia.

The political superstructure of the United States has always fulfilled the order of the financial and industrial oligarchy – back in the first half of the 19th century, the “Monroe Doctrine” was proclaimed. According to it, North and South America were proclaimed a zone closed to European colonization. It was assumed that it would be dominated by the States. At the end of the 19th century, the American government pursued a policy of expanding economic influence in Latin America and Asia.

The administration of US President William McKinley (March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901) believed that it was time for the United States to acquire its first colonies, which would simultaneously be sources of raw materials and sales markets. In addition, Spain was weak and could not defend its colonies by force, inflict great damage on the United States, and did not have powerful allies. The capture of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippine Islands solved the problem of strengthening the strategic position of the United States in the Caribbean, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

The United States carried out successful preliminary work in preparation for war: an information campaign in the press about “Spanish cruelties, and in 1895 in the territory of Puerto Rico and Cuba, and in 1896 in the territory of the Philippine Islands, the national liberation struggle against the Spanish regime “began” . For example, the Cuban Revolution began with the fact that a detachment of José Marti landed in Cuba (he was helped to create the Cuban Revolutionary Party in the USA in 1892). The Cuban rebels were ruthless, destroying settlements, plantations, industrial enterprises. The Spanish governor-general responded to cruelty with cruelty. In Cuba, the uprising was almost crushed, the peasants were herded into concentration camps, thus depriving the partisans of support.

The American press threw a tantrum about the “bloody Spanish regime”. The US Senate recognized the rebels as a belligerent and demanded that the Spanish side resolve the conflict amicably. The Spaniards, in turn, said that the Cuban unrest is an internal affair of the empire (reading this, you understand that the current unrest in Libya, Syria, the situation around Iran, repeat the scenario more than a century ago).

In the eyes of the world community and the American inhabitants, the United States wanted to look like “liberators”, so a pretext for war was needed. But the problem was that Spain did not want to fight.

“Remember Maine!”

At the end of January 1898, the American armored cruiser Maine arrived in Cuban Havana. Although the Americans claimed the friendly nature of the visit, it was clear that this was a challenge and a demonstration. The Spaniards were forced to allow this visit.

February 15, 1898 there was a terrible explosion and the ship was lost. The explosion occurred in the evening, when the crew was on the ship and the sailors were sleeping, so there were many victims – 261 people died (the standard crew of the ship is 355 people). An interesting fact is that almost all the officers were on the shore, and the dead sailors were mostly blacks. The United States blamed the explosion on the Spaniards, who planted a mine under the ship. Although the Spaniards, who did not want to fight the United States, did not need this action, there was no motive, unlike the Americans.

Although the Spaniards, who did not want to fight the United States, did not need this action, there was no motive, unlike the Americans.

Almost immediately, a number of questions arose that disproved the American version. According to experts, such an explosion, which broke the ship in half, could not have come from a mine (it would have formed a hole in the underwater part of the cruiser). Therefore, the explosion, apparently, occurred inside the cruiser “Maine”. Other facts also pointed to this: the absence of stunned fish, which would have been in an underwater explosion, broken windows of surrounding buildings.

When they tried to raise the ship to the surface already at 1910, this version was confirmed, people learned that the explosion occurred inside an armored cruiser, and not from a mine or torpedo. And also that the steam boilers were intact, so the version of their explosion was excluded. In addition, in 1911, the Americans unexpectedly curtailed all work on raising the ship, all documents related to the investigation into the death of the cruiser were classified. The bow of the ship, mutilated by the explosion, was cut and melted down.

The bow of the ship, mutilated by the explosion, was cut and melted down.

Contrary to the facts that pointed to an internal explosion, the American commission quickly completed its business and left for their homeland. The reason was created – “The vile Spaniards blew up our cruiser with a mine.” The slogan was thrown into society: “Remember Maine!” 19April, the United States demanded that Spain abandon Cuba, at the same time the mobilization of volunteers and the deployment of the fleet began. Already on April 21, without a declaration of war, American ships began to seize Spanish transports heading to Cuba. On April 22, the American squadron of Rear Admiral Sampson opened fire on the coastal fortifications off Havana.

Strange War

The campaign was fast and with relatively few casualties. In general, it was a somewhat strange war. The first US soldiers died only two months after the start of the war. They fell off the side of the boat during the landing and drowned. The Spanish soldiers, completely devoid of motivation for war, morale, saw a heavy burden in the colonies and dreamed of returning home.

The Spanish soldiers, completely devoid of motivation for war, morale, saw a heavy burden in the colonies and dreamed of returning home.

The main fighting took place at sea. The American ships were more modern and surpassed the Spanish in almost all respects – the artillery of the American Navy was 2.5 times more powerful and had a higher rate of fire, superior in armor protection. The Spaniards neglected combat training in the pre-war period: there were no maps, no plan of action in case of war with the United States, ship gunners did not practice shooting, the general level of crew training was extremely low.

The financial possibilities of the States and the Spanish crown were not comparable either. Spain did not even have enough money to buy coal for the needs of its Navy.

The result was sad: the Spanish squadron was completely destroyed.

The Spaniards sued for peace having lost their main fleet – the war was lost. The United States during the entire war lost only about 500 people killed (much more died from diseases and wounds – about 6 thousand people), the Spaniards more than 2. 1 thousand people (there is no information on the number of deaths from diseases in the Spanish forces, but apparently not less than Americans).

1 thousand people (there is no information on the number of deaths from diseases in the Spanish forces, but apparently not less than Americans).

“Kill all who are taller than the cart axle”

On August 13, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed. The Spanish side was forced to abandon all its colonies in Asia and Latin America – the Philippine Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico and Cuba. The first three territories became American possessions, for which the United States paid the Spanish crown $ 20 million in compensation. And Cuba was proclaimed an independent republic, but in reality it became a “banana republic” and a “brothel” of the United States. Its foreign policy, economy, finances were under complete American control. An American naval base was established in Guantanamo Bay.

The United States brilliantly tested the scenario of its future wars: information warfare (the enemy is mixed with dirt even before the start of the “hot war”, turning into a “bloody monster” in the eyes of the world community), brilliant use of the discontent of the population, organization of “people’s liberation” movements ” , provocation, “pirate” war (control of communications, naval operations, landings, etc. ).

).

Spain finally lost the status of an important colonial and maritime power. But the United States received the status of a great maritime power, the American Navy after the battle of Santiago de Cuba was recognized as one of the leading fleets of the planet.

The Spanish-American War demonstrated to the entire world community the strength of a young predator, a new great power appeared on the world map. The war opened a new era in the history of the United States.

The Philippines was not so easy to deal with. The inhabitants of the island decided to become free and started a war against the United States. The Philippine-American War continued until 1902 (active phase), and individual units resisted until 1913. The US had to send 125,000 troops against the Filipinos. The Americans did not hesitate to use the most cruel methods, which was typical of the European colonialists, so if about 20 thousand people died of Filipino soldiers, then 200 thousand civilians.

Pacific Current Season Summary

Pacific Current Season Summary

S. Virgin Islands (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)

S. Virgin Islands (high tide scenario) (Updated 11/30/2018)